Here’s the pitch: Today we’re reviewing one of the most exciting games to cross my path in a good long while.

Before we get started, let’s take a moment to thank Osprey for sending us a copy to review. Thanks Osprey!

Xenos Rampant is the newest game in the Rampant series from Daniel Mersey and Richard Cowen, published by Osprey Games. Straight away if you’re aware of what Mersey and Osprey have been putting out recently, you know you’re in for a few things:

- Great rules

- Fast play

- High production values

Game delivers. Mersey is the designer responsible for Lion Rampant—medieval skirmish battle rules—and, with various co-writers, all the myriad solid rules that Osprey have spun out from that. Pikeman’s Lament for the 17th century, Dragon Rampant for fantasy and now, based on the updated 2nd edition Lion Rampant comes Xenos Rampant. These are Science Fiction wargame rules that deliver a 21st century wargaming experience: fast, fluid, customisable and flexible. I think, if there were justice in the wargaming world, Xenos Rampant could be THE far future skirmish game, and it’s much, much more than just another set of scifi rules. Let’s dive straight into why.

What are we looking at here?

Xenos is a miniature-agnostic skirmish wargame for science fiction settings. It could be played at 28mm in a grim dark galaxy, it could be used to cover near-future grounded combat, it could be just the rules you’ve been looking for to do the Weird War 2 campaign you’ve been thinking about, or simply to throw whatever you and a friend have to hand onto the table to crank out a fast, enjoyable and deceptively simple game. It’s got heroes and villains, vehicles, aliens, soldiers, shooting, high-tech and high-concept, explosions, psychic powers and everything you could want for your Scifi skirmish, all built on a solid grounding of clear and flexible rules.

In a full colour, well produced and proof read 192 page rulebook with great art and illustrations (fantastic art by Michael Doscher) throughout, you get a ruleset that’s easy to pick up and difficult to master, astonishingly broad and flexible army selection rules, a campaign system, multiple scenarios and even examples of genres and settings to let you get started exploring the game in several different ways.

There are two major selling points for me here: clear, clever rules and the amazing flexibility of the army building system. This is a set of rules where you can take any model you want and build it within the framework the game gives you. The possibilities are almost endless, and that is bloody exciting.

The Rules

We’re not going to go through the entire rules system of Xenos Rampant one bullet point at a time, because – for one – it’s a short, easy to understand system (only 28 pages, and that’s with lots of miniature photos on half-page display), but also to highlight a few systems that speak to the philosophy of the game as a flexible, fast play experience.

Xenos is an activation and action based system, so if you’re coming in from strict IGOUGO games like Warhammer 40k, be prepared for learning a new system that—in my opinion—makes games all the better. We’ve talked (at length) about activations on Goonhammer before, and many of our favourite games have some form of alternate activation system. Xenos goes for a straightforward Activation test (2d6 rolled against an activation stat) mechanic, but with a clever twist. Units have several actions they can do when activated, built around a core of move, shoot and attack (melee) and additional reactive activations.

The active player activates units until they fail to pass an activation test, and that failure hands over control to your opponent. Not all your units are guaranteed to activate, and that, at the most basic level, builds tension and meaningful choice into the game. You need to prioritise what you’re doing, who’s moving, or shooting, or chopping the opponent into pieces, and at any moment you could fluff that test and hand the initiative straight over to your opponent who’s been itching for revenge since you fired your first shot.

You get this kind of thing in a lot of games—as someone who plays a lot of historicals games the test to activate system is familiar ground. Where Xenos has a clever little ripple is that each action you can take with a unit has a different activation value. Straight off the bat, that lets the game differentiate choppy units (who will easily activate for a charge and subsequent melee), shooty units (who’ll shoot easier) and mobile units. Elite units will activate easier on all three, while raw, untrained mobs of models may be difficult to activate. Elite units might even get a free activation, while some may lack the option to activate specific abilities at all. Your artillery, for example, might activate for free to shoot but will not be charging into battle.

I like this a lot. It provides very simple and very effective differentiation between units. It shows variation in expertise, inclination, unit quality or purpose quickly, subtly and intelligently in a way that is instantly understandable both to you and your opponent. It can be used to easily draw character, background and story out of your army and does so in a rules-supporting way, fluff and crunch working together to deliver a satisfying choice-filled mechanic.

This kind of easy to understand but deeply impactful rules design works throughout the game. Rules that could, in other systems, take up multiple pages are reduced to their essentials, streamlined for better and more effective gameplay. Units shoot, fight and lose models according to general principles, like rolling ten dice for shooting if your unit is above half strength, or unit morale being split between fine, suppressed, and fleeing off the table. Everywhere, if a rule or system adds needed complexity to support a satisfying play experience, it’s kept. Shooting is a great example – you hit by rolling your shooting value or above. You wound by comparing the number of hits to the targets armour value, with a few modifiers. Done. Anything else that you really don’t need – like, say, rolling to hit, to wound, to save against armour and to mitigate damage all separately – is removed. It’s tight as hell, and that’s a pleasurable play (and reading!) experience.

The other major rules system worth drilling down on is Strength Points. For the players, strength points are your wounds/model removal/fighting strength and morale mechanic. More SP means a bigger unit that can take more damage, stay in the fight longer and be more effective as it takes hits. Units deal out SP damage in shooting and combat, and take it in shooting, combat and morale tests. A unit above half its SP value fights and shoots at full strength, a unit below takes penalties. It’s quick, it’s easy to remember and it tracks your diminished fighting strength as you take damage. Units with lots of SP remain effective for a long time. Units with fewer are more fragile. So far, so simple.

To the designers though SP opens up a range of model possibilities that allow for a huge range of flexibility. As everything a model can do (except activate) works by SP total, you can use those numbers to express the differences between all sorts of units. A unit of elite infantry in giant mechanical exo skeletons might have five strength points, but only three models, a giant horde of 45 zombies might be fifteen strength points, or a genetically engineered warrior strapped in a walking coffin armed to the teeth could be on his own, but have ten SP. In each case, your models and your SP are not one-to-one, but it remains a very simple to track and calculate mechanic that changes up the nature of your units. The Walker-Coffin is tough as hell, the zombies you’ll remove by the handful every time a unit shoots at them. As SP total affects fighting strength, it’s always meaningful, and model removal becomes something visually and conceptually interesting, rather than just a process you go through to represent lost wounds.

Anything Goes

A miniature agnostic, fast playing, highly customisable Scifi skirmish wargame? Have Osprey pulled it off with Xenos Rampant? Hell yes they have! Models and miniatures—and the freedom to play with them— really is the heart of the system. It’s interesting and telling that Xenos Rampant doesn’t start with a rules section. It starts with how to build a detachment for the game, because this really is about making a system that works with anything you want to play with.

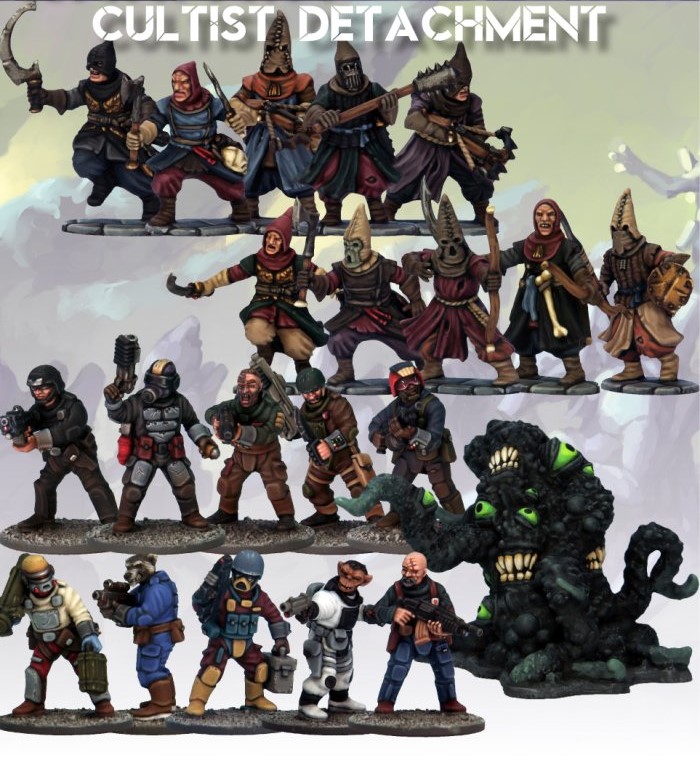

There are a plethora of unit types all built on the same basic statlines – activation scores, courage, fighting and shooting ability, movement and armour – and the simple variation in these values gives the game it’s basic unit archetypes. Profiles cover Scifi staples like Elite Infantry, Beserkers, Giant Xenomorph monsters, hordes of chittering lesser aliens, military and civilian vehicles and transports. 13 basic unit types cover every eventuality, and if the game stopped there, you’d be able to consider it a pretty flexible system able to fight just about any kind of battle. But it doesn’t, because when Xenos says miniature agnostic, it bloody means it.

On top of those 13 basic unit types, there are 30 additional rules for infantry, 18 for vehicles and 35 “Xenos rules” representing weird and wonderful abilities. The core infantry and vehicle additional rules are things like Armour Piercing (reducing an enemies effective armour value when shooting), or Mobile (faster movement), and 30 different options, variably available to the 10 infantry archetypes, cover an awful lot of ground. You can design virtually anything you want from these – and the same goes for the three types of vehicle and the 18 vehicle options. All of these options are very simple mechanically, explicable usually in 1-3 lines of text and come with a points value as an upgrade or downgrade.

You’d struggle to find a unit profile in a Scifi skirmish game that couldn’t be expressed through these, and if you can it’s likely that it will be found in the Xenos rules – 35 exotic and slightly more complex additional rules that really bring the weird. Xenos rules include a set of psychic powers, rules for zombies or other brittle, mindless styles, zealous crusaders, high-tech weaponry or cloaking devices, force fields, powered weapons, robots and paratroopers.

It’s a phenomenally massive range of customisation that means you can put anything you like onto the field, and have it work as you’d like – and how the models portray it. It’s obviously a fantastic narrative opportunity to have the means to put whatever you want onto the field and have it backed with rules, but it’s also a great mechanical one. Every building block you need is here, with a points value, clarity on any interactions (can’t stack anti-tank and armour piercing, for example) and easily explainable to your opponent. You can go as strictly WYSIWYG as you like, or combine with the Strength point system to stick some bizarre and fanciful creations on the board.

If I sound excited by this, it’s because I legitimately am. It’s all in service of the shining idea: a pickup, narrative or campaign game played with whatever models you want. You can tailor your force to what you want to play mechanically, thematically, asthetically, and you could put this against a force that your opponent has done the same with. Giant Mechanical Squid and it’s horde of mind-controlled civilians against Soulless Vampire Knights mounted on naked mole rats? Yep. Marines (from Space, mind you) versus Paradropping Aztec psychers? Sure. It’s not even that these forces would seem painfully generic as in many games that claim to be miniature-agnostic, because the rules back up meaningful differentiation and provide solid crunch to back it all up.

Let’s take my Horus Heresy Ultramarines as an example. A couple of units form a 24 point force.

I want this to be a big walker backed up by solid infantry and wily light troops, so I use three basic archetypes. My Guardsmen become Light Infantry, my Marines Heavy Infantry and my Dreadnought Elite Infantry. They’re differentiated already, but I want to make sure they’re very different on the table so I add some customisation options. The Light Infantry get Armour Piercing to reflect their precision fire. The Heavy Infantry get Increased Squad Size, Fanatical Discipline because they know no fear and Heavy Weapon because they’re rapid firing mini RPGs. The Elite Infantry is a reduced model unit – one model standing in for five strength points. He’s very very tough, so gets Super Heavy Armour, and he’s also very good in melee with Assault Doctrine, while his array of guns give him Anti Tank to boot. Each unit uses a different archetype, but also fights very differently – and fluff appropriately – based on their abilities.

Isn’t that Enough?

It’s not just the crunch, though, and Xenos Rampant also provides a campaign system and multiple example settings for you to explore. The settings are fine, a full third of the book dedicated to exploring various Scifi genres, including alt-history, modern dystopian and full on far future warfare. There’s a lot of movie, videogame and tabletop inspiration here and straight out of the book you could refight WW2 with werewolves, recreate Battle: Los Angeles, or take Necromunda to a large skirmish level. For people who got seriously freaked out by the enormous possibility presented by the army selection rules, or who get massive decision paralysis, the example unit types and genres are going to be very useful. If you’re coming from a more hand-holdy system of gaming, they’ll be dead handy to get you going with Xenos rampant. On a personal level, I don’t need them so much, though they provide a good take on how to play in a Scifi sandbox.

The campaign system and the commander traits that accompany it are probably the one weaker point in an otherwise fantastic system. This isn’t where you look for a fully fleshed out, granular campaign, and that’s fine – lots of other products for that – and the campaign rules presented are light touch stuff mainly focused around improving (or eating!) your commander. The commander trait rules though are quite lolrandom, a set of d6 tables with several ok, one spectacular and one or two negative traits per, and that doesn’t sit right with me. I love narrative play, but not where the narrative is based around “if you roll a one your commander is shit”, particularly where a commander trait might take away army list points when your opponent just got reroll shooting misses. Luckily, they’re easily skipped, or houseruled, and therefore not a major issue.

Rampant Indeed

So it isn’t all gold, but nearly everything in this system is at least silver (slightly lost the metaphor there). You can learn Xenos Rampant in ten minutes, but mastering it and working with the activation system will take a gratifying amount of concentration and effort. The rules are generally great, a fantastic set of strong bones you’ll be able to play with and enjoy time and time again, but where the system really takes off is the flesh that fills out the bones – the weird, wonderful and intuitive list and unit construction that I don’t think you’d ever really get tired of. That’s the whole intent of Xenos when it comes down to it, that you grab some favourite miniatures, or some new stuff you’ve never had a system to play with, designing a fun list with clear rules and just getting down to rolling some dice in a player-choice driven game. If we’re all lucky, Xenos Rampant will become a solid fixture of games nights and the wider community space – as a game, and as a system to get us playing with our favourite minis in whatever worlds of Scifi we care to explore, it deserves it.