If you haven’t heard of award winning game designer Jay Dragon, well, you’re missing out. Jay’s games Wanderhome and Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast have been huge hits in the TTRPG world and it’s definitely worth keeping an eye out for what’s next from Possum Creek Games, where Jay is editorial director.

It’s also worth following @jdragsky on Twitter for tidbits about upcoming games and some very thoughtful and interesting takes on game design and theory. That’s where this conversation started, actually. If anything good is coming out of that app these days, it’s connections with cool people who are also still using it for some reason.

Here’s the post that finally got me to reach out to Jay. Click through and read the thread and replies if you want a bit of extra context to the conversation.

I messaged to ask if we could talk further about that topic, and Jay graciously agreed! We… got a little off topic, but I’ve cut this down to keep it focused. So, welcome to a conversation with Jay Dragon about the role of rules and game designers in roleplay games, lightly edited for length and clarity.

What’s the least roleplay game you’ve told a story in?

I think for me, City: Skylines. I do a lot of role playing when I play that, because I have a lot of feelings on City: Skylines. It’s this kind of neoliberal model. City: Skylines, if you’re not familiar, is a deeply simulationist city building game that, like you put your water plants downstream of your sewage plants, your cities get cholera. It’s incredibly detailed and minute, but when a house is destroyed, like if you destroy a neighborhood to build a new road, there’s no homeless people.

It’s a game that is very selective about what it models, and it’s this very particular neoliberal mindset of what is important or not important to a city. If I was to engage with it honestly as myself, I’d be like, “I don’t want to play this.” The way I find fun is I pretend to be Robert Moses, and I get really into it. I have a blast being like, “Time to gentrify!”

That’s hilarious.

“Time to build a freeway! They’re complaining about traffic, those little bitches.” It’s really fun.

That is so funny. So, do you think we need game mechanics to get people to roleplay?

There’s a lot of fun to be had in playing and also in the adopting of roles. I think those are both very fun, and I think we can see, both historically and in the present, that both of those activities are very fun, and they can be very fun without involving each other.

What is roleplaying without a game? I think universally, there are going to be codes of behavior that shape how people engage with roleplaying. A roleplaying game makes those codes of behavior explicit rather than implicit. What happens if you take away a roleplaying game? Well, you get improv comedy.

If you say improv comedy is a role playing game, that the rules of improv are taught to the players and they’ve internalized them, then you go, Okay, what is improv comedy without rules? Then what we’re describing can get into kind of unscripted theater. You can get into like, ren faires.

I think that role playing and games are not necessarily synonymous, but they both emerge from a similar fascination. And I think that RPGs do interesting work when you make the expectations around role play explicit instead of implicit.

Now I’m struggling to think of an example of roleplaying without rules. At least in my experience, even being a kid, there were some understood rules.

I talk about this with my ideas of “systems of relation,” which is the idea that rules are frequently non mechanical. To me, “house” is an RPG, and the system being used is the nuclear family itself.

You’re taking the real life system of the nuclear family, and you are running it on the hardware of these children. We’re producing a play form that is running on the logic of the nuclear family. The relationship of the mother and the father and the kids and the dog.

Me and my best friend as kids would play a superhero and super villain, and that was the logic of the media we were engaging with as children to role play. We’re using the implicit systems we learned from that, rather than explicit- obviously, we all know the superhero always wins. We don’t need to codify that. We just know that intuitively in our roleplaying.

This is bumping into one of your Medium blog posts, which has a great title, “Rules Are A Cage (and I’m A Puppygirl).” Love that. That’s about friction from TTRPG rules. I’m wondering, with some of this resistance to put game mechanics in storytelling games, are people worried about or afraid of that friction?

Here’s actually an interesting thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot: One of the critical differences to me between video games and tabletop RPGs is about positive space and negative space.

In a video game, you begin by being able to do nothing, and then the game designer presents you with things and gives you inputs. If you’re playing Mario, you are presented with a vocabulary of action, and you can only violate that if you change the game itself, or if you mod the game.

A great deal of playing video games becomes engaging with that vocabulary as strictly as possible, whereas in a tabletop game, if we have a tabletop game with no rules, that means anything is possible. If you have a video game with no rules, it means the screen is blank, but a tabletop game with no rules means anything is possible. There’s infinite possibility.

The game therefore starts closing the doors on what is possible and limiting and sculpting you and positioning you in a certain way. I think that mirrors the implicit rules of storytelling.

If I say “Once upon a time…” the sentence that follows could be anything. “Once upon a time, there was a princess in a castle-” I have suddenly, immediately closed the doors on 1000 things, and I can open those doors. I could be like, “and one day, she opened up her phone and checked Tiktok,” and I’ve opened a door you didn’t think was open. I can do that on purpose, but I’ve opened a door that was closed. That’s different than if she went to her magic mirror, right?

I think people see the way in which RPGs cut off that possibility space, and it feels much more like storytelling than when in a video game, you begin with nothing and existence is granted ex nihilo to you by the developer.

I do think that’s part of why people talk about, “Oh, if you play TTRPGs, you can do anything.” And what you’re saying is, sometimes, it’s “you can do everything except that,” and that’s where the game system is.

Yeah, and that’s fun for me. I can do anything, I can imagine anything, whenever I want. I don’t need a particular RPG to give me permission to imagine something that I couldn’t imagine before. It isn’t like, “Oh, I’m gonna play the superhero RPG, because there’s no world in which I could be a superhero otherwise.” No, I can imagine being a superhero doing anything. I’m interested in a superhero game that says, like, “Your feelings are gonna matter more than the fights,” or it’s a superhero game, but you’re always doomed to tragedy or something. There’s something there that makes it kind of pop for me because of the way it limits me.

Is this the way you’re thinking about designing games?

There’s going to be a set of things that I am able to imagine and a set of things that I’m not able to imagine, and I want to build a space that is sufficiently compelling that it can produce both. Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast, for example: That to me, is a space that is very interested in thinking about community over time. That’s kind of the central crux of that game.

There are certain things where I have a good sense at this point- what chapter did you play?

Let’s see… I played two. One of them was about fishing and one of them was making breakfast. (Luke’s note: Chapters in Yazeba’s are like vignettes or one-shots. The chapters I played were chosen by a game facilitator at Gen Con. They were great choices for con play, with clear objectives that meant a table of strangers didn’t necessarily have to mesh or get into serious roleplay to have a good time.)

Yeah, those are both chapters where I have a pretty good sense of how they’re gonna go. That’s not because I want them to go a certain way, it’s just because when you put in these inputs, you produce this output. The fun of it is that it goes that way. There are other chapters where I don’t know how they’re going to go.

More importantly, when you start putting the chapters in sequence, when you start changing the characters, I don’t know what directions they’re going to go in. To me, the fun of Yazeba’s is that it’s less that I need it to produce an output. If you played the breakfast feast and Parrish and Hey Kid had ended up fighting each other and blowing up the kitchen, I don’t consider that bad. I think that’s interesting. I think that’s a cool, if unexpected outcome from how things went. It’s the fact that things in sequence, when you start putting them together, start becoming like that, is what I’m interested in building.

Seven Part Pact, a game I’ve been working on a lot, is this wizard game where there’s an incredibly dense simulated mechanical structure that’s almost like a board game that’s tilted towards your failure, unless you cheat using magic. That is a system where I’ve built this edifice of patriarchy, of power, of establishment, of authority. I don’t actually care whether or not you want to play a wizard who reifies it and embraces it, or a wizard who rejects it and works against it, because I’m interested in “Here’s the edifice or here’s the structure.” Whatever you want to do with that is interesting play.

If you want to climb all over it, or if you want to try to tear it apart, or if you want to ignore it and shuffle around in the sand, those are all meaningful things to do in its presence. I’m not going to build the machine that guides you to a conclusion. I’m much more interested in being like, “Here is this great machine,” and watching people interact with it, because I’m interested in the variety of responses it provides.

So someone could either use the machine or try to break it and see what happens.

Exactly, that’s all part of the art response. I’m interested in producing games that are apathetic to the emotional response of the players. I’m less interested in building a game that produces a feeling, and more about building a game that creates space for a variety of feelings.

You know, in the D&D world at least, there’s a conversation about “Why would you want some form of systemic oppression in your world?” that drives me insane, personally…

At so many tables, we’ll be building our characters, and we’re all adults, and we’re playing a kind of intense game, and someone will be like, “I want to make sure there’s no oppression.” I’ll go, “Okay, tell me more about that line, because my character is very much about systems of power, or my character is struggling with emasculation” or what have you. I want to understand if this line that you’re setting is something you don’t want happening to your character personally, or is this something you’re setting because you don’t want it in the story at all? They’re surprised that I’m interested in those sort of stories, which is wild to me. And frequently they realize, “Oh, I was just saying that because I felt like I had to.”

It’s tough, because I can totally see, you know, a person of color saying, “I don’t want to see racism in the story,” and I’d go, “That specifically? Gotcha.”

It’s trust. It’s a thing where if you are a person of color and you’re sitting down at an all white table at a con and you say “no racism,” that is entirely reasonable. Similarly for me, if I sit at a table and realize I’m surrounded by cis guys, I’m gonna say “no transphobia,” because I’m not sure any of you will handle it right. Maybe you can, but I need to learn that you can. Ideally, we’d build up to it.

I’m interested in games that really delve deep into painful and difficult topics. I’m really interested in games that really kind of poke at and complicate and interrogate our social assumptions. That means I want to do games about, sometimes, really awful people and I want to fucking tell adult… We’re fucking grown ups. I don’t want to Marvel movie my way through my RPGs.

To do that requires trust. To do that requires intimacy. It requires people that I’m playing with, where I’m confident that we’re all on the same page about our artistic goals and our understanding of each other. There’s a certain level of TTRPGs where you are artistic co-collaborators, making a work of art together. If you’re going to be making art about difficult things, you’ve got to trust each other and also trust your audience, which is ideally just the other people you’re playing with. It’s the same way that you couldn’t make Breaking Bad if you didn’t trust that the people watching Breaking Bad understood what you were going for.

Also if you say, “I don’t want oppression”… that’s just too broad. What is the story? What are we talking about? Are there people who are richer than other people? Are there people who are… I don’t know, other people’s bosses?

In my wizard game, Seven Part Pact, “all wizards are men” is a really critical claim the game makes, and it’s undermined in the text of the game. I’ll have people be like, “Well, why? Why are all wizards men? What happens if a woman is a wizard?” It’s like, sure, a woman could be a wizard. It’s your game. Go nuts. What happens then, though, is that she’s Margaret Thatcher. The reason why all wizards are men is because wizards in the society represent the apex of authority and patriarchy and concentrated power. They’re walking nuclear bombs. They are legislators who can kill the king at a moment’s notice. They’re extra-legal structures of authority. They represent all this power and imperialism and hierarchy and control.

When you make one a woman, you haven’t negated any of that hierarchy and control. You’ve just made a woman who now has to act twice as vicious, twice as toxic, twice as masculine, in order to assert and establish that she belongs there. So if you want to go in that direction, sure, but you don’t actually undermine the system. Like was Margaret Thatcher successfully utilizing girl power when she committed genocide, right?

You know, we need more women in war crimes. That’s always my complaint.… Well that was a tangent.

Back to the original topic: Is there something like that you think more people should be considering when creating a game and game mechanics?

I’m always really preaching that “show, don’t tell” is meaningful game design advice. First off, I think it’s important to understand that when you are making a game, when you’re making a tabletop game in particular, the thing you are making is not itself, strictly speaking, a game. You are describing instructions for producing a game.

Maybe I’m answering this question entirely backwards, but get to the crux of it: You need to understand why people want game designers. Bernie De Koven talks about this in “The Well-Played Game,” which is a great book by the way, where if you’ve got some players and they want to play a game together, and they want to play- Let’s say we want to play with little tiny soldiers. We could, if we wanted to, invent a game from scratch. It’ll take a lot of work and a lot of trial and error, and there might be long moments where we’re not having fun and it might feel frustrating. We’ll eventually get there, but it’ll take time if we don’t know how to really iron those things out. It might be a lot of negotiation.

When we want to play for a couple hours, we don’t want to have to go through a long and arduous process of creation to get the thing we want. So we go to our buddy who is a game designer. We trust our buddy to have thought about this and to have play tested this, and to provide us with a set of pre-negotiated rules that we can bring to our experience and play. We trust, because our buddy has pre-negotiated that, that we’re going to have fun doing that.

When we would have to figure out how to handle it when a tank shoots a building, thank god our buddy figured that out already, right? Thank god, we’ve already negotiated that, and we can just trust that the rules are good.

When the rules aren’t good, when the rules haven’t been tested, when the rules are hodgepodge and they produce situations that we don’t enjoy, where one person’s not having fun, where it’s no longer a well-played game, we feel betrayed. It’s like we trusted our buddy, the designer, to give us a thing that would be fun for all of us. As a game designer, you have a tremendous amount of trust on your shoulders.

You want to make something, but the thing you’re making is not necessarily itself the game. You’ve built the thing, you’ve tested it, you’ve experienced, experimented with it, you’ve built tools for it, you’ve built mechanisms that kind of assist with it. You collate it all and say, “This is how I’ve played and I’ve had a lot of fun doing it. I’ve put it in a book and I’m gonna give it to you. If you do it, you’ll have the same kind of fun I did and I hope that’s fun for you.”

That’s not itself, technically, a game. Technically, the game is being interpreted from that text in the same way that a script is not a play. The play is an interpretation of the text. You’ve got to know all that. You have to understand, you’re making not the act of them reproducing, but rather your aid in their reproduction. You’re creating tools for them to produce.

Finally, finally, through all of that, if that is all true, you don’t want to be thinking about, “How can I make them feel? ” or “How can I control them in having an emotional reaction?” There could be impulse to control, to produce an emotional reaction. It’s not really meaningful.

Instead, what is very valuable is- for example, going back once again to my wizard game, thinking about power, thinking about patriarchy, thinking about masculinity. In that game, you are incentivized to not pay attention to your wife until you need something from her. She is just kind of a figure quietly doing the dishes in the background of your life. Sometimes you need something from her, so you go to her, and you spend time with her and take her on a date, and then sometimes she gets hurt. Now no one’s doing your dishes, and your dishes are piling up, and you can’t cast certain spells because your office is too much of a mess, and that sucks, but “Oh shit. I need my wife. I gotta go get her back.” She’s invisible to you until you need her.

That is a game mechanic that is not about making you feel a certain way. I’m not really invested in being like “and that makes you feel angry or that makes you feel sad.” I’m just interested in being like, “Here’s how the world works.” The question is are you going to let that be or are you going to spend time with your wife, even when it’s mechanically suboptimal to waste time on your wife.

That’s great, that’s fun. That’s interesting to me, because it’s apathetic. Here is the way things are, and the story will emerge from the way things are. I want a game that is just like, here is how, here’s how things work in this world. Maybe the way things work is really silly, or it’s tropey. If I’m playing a wuxia game, it’s like, yeah, the way things work in this world is absurd. It’s wuxia. It’s people gliding around with their swords. It’s not concerned with realism.

Yazeba’s, I like to joke, is a simulationist game that is simulating a narrative world. It’s simulating a book, but it’s not itself actually that narrative. I’m just interested in providing the mechanisms of the world. What emerges from that, what is the next step after that, is to me, what’s interesting. I think that game designers would benefit from letting go of the impulse to be like, “and then this mechanic is going to produce this plot point, and then this plot point.” The kind of impulse to be like, “and it’s going to make you feel angry and sad, and I want to get you to feel these ways.” It should be more, “here are the mechanisms, here are the operations, and I trust that things will emerge from it that are compelling.”

Jay, thank you so much for taking some time to chat! This could’ve gone on for another hour and I would’ve been thrilled the whole time.

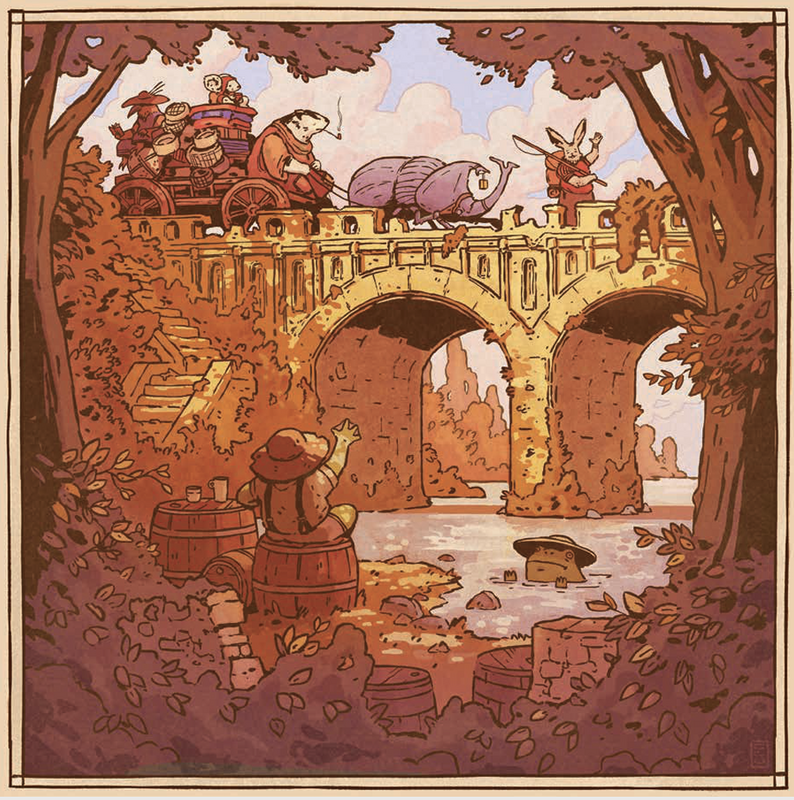

Everyone else: thanks for reading! If there are more game designers you’d like to hear from, or more game topics you want to get some perspective on, let me know and I’ll reach out. My Twitter is @luke_taylor23. Also, again, play Jay’s games! That cozy, pastoral art you’ve probably seen is coupled with some extremely fun and unique game design.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.