For all the endurance of plastic, resin and metal, the games we play are often fleeting and ephemeral. Warhammer and its spin-offs, De Bellis Antiquitatis, and Battletech (among others) are all pushing towards 40 or beyond, but the history of tabletop gaming is littered with lost, dead and abandoned games. On a personal level, we’ve all bought in – fallen hard – for a game only to have an unjust, untimely cancellation (and, ok – sometimes a totally justified one) break our hearts and leave us with questions voiced only on mid-00s BBSs.

When it comes down to it we don’t really know, as a community, how and why games end and we’re not used to analysing them when they do. Does every game that ends fail? Are there clubs somewhere out there where long-defunct rulesets are frolicking in their well deserved retirements, faithful steeds put out to pasture? Do games ever really go away? Why, and what happens to them when they do? Today, we’re asking that question about Starship Troopers – a game which is increasingly fading into memory, but at one time looked like it might just be the one to steal Warhammer 40k’s crown. Today we’ll talk about the history of how Starship Troopers came into being; in part 2, we’ll look at what caused its dramatic fall.

Starship Troopers: Rise

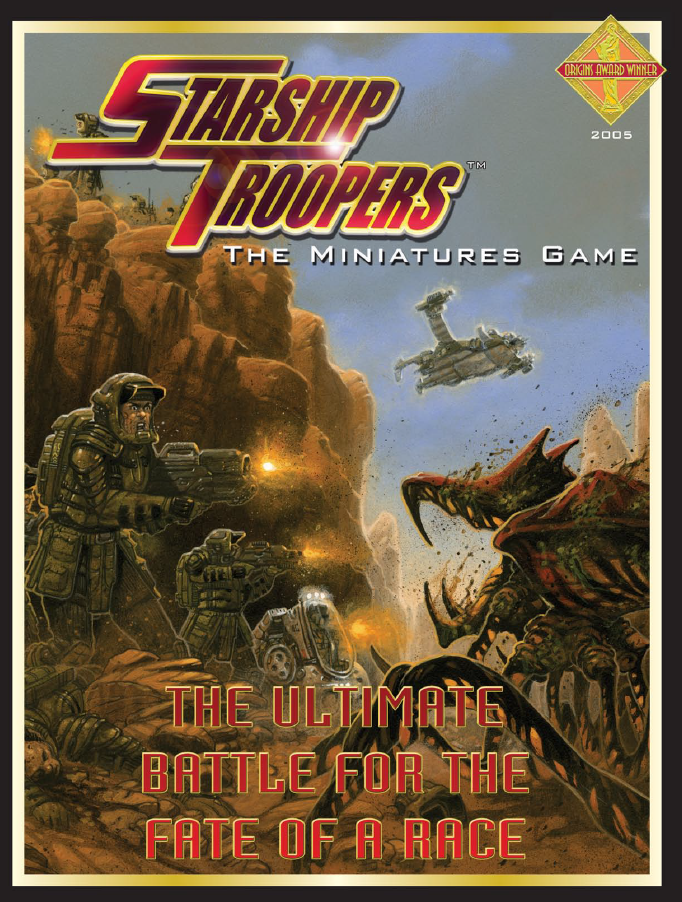

Northern England, 2005. It’s pissing it down and I’m waiting for the bus when my trusty 3210 buzzes – a text, something along the lines of STRSHP TRPS GM FKIN GD, from a friend waiting for me at the Chesterfield Open Gaming Society. Starship Troopers: The Miniatures Game WAS fucking good, and I hunted it out at every con and played every demo game I could find. Heavily varnished black bugs, tiny orange visors and a rule book by Andy Fucking Chambers of all people were absolutely everywhere in the gaming scene until I headed off to University. When I got back home the miniatures were still there – but the game wasn’t.

Starship Troopers: The Miniatures Game exploded onto the tabletop scene in 2005, rode an intense and brief wave of mass popularity, and vanished almost entirely within three years. Produced by British not-quite-indie Mongoose Publishing, it’s often considered one of the great lost wargames. A plastic starter set with gorgeous, movie-looking bugs, a beautifully crafted ruleset, and a wide range of metal releases promised a long and self-sustaining life. Instead, the game is now not just “dead” but almost semi-mythical; the great shining city on the hill, the alternative to 40k that could, and maybe should, have been. Within three years, the game had appeared, peaked and vanished, now only spoken of wistfully by gamers in their mid thirties and upwards, an exciting time when everybody dropped, and everybody fought.

The landscape of tabletop gaming in 2004-5 was not so different from today. A monolithic Games Workshop, a scrappy collection of underdogs – many still familiar names – and a plethora of indies, all competing for a market share that just kept on growing. Tabletop gaming was starting to find a place in the mainstream, pushed there by the relentless phenomenon of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, forcing previously nerdy culture firmly in the public eye and keeping it there. LOTR, Dawn of War, and the Black Library had skyrocketed Games Workshop into an all-time sustained stock high, a massive boom then into its fifth year.

Cracks were starting to appear in the monolith, however, and within the industry it was clear that spaces were opening up. As GW turned ever inward, with obsessive cost-cutting on the one hand paired with taking on strange risks and partnerships on the other, all the while whittling away the creative old guard who had shepherded in the 00s boom, the underdogs and indies circled round. In the US, Privateer Press, WizKids, and Fantasy Flight Games were putting out big, exciting content, with both new editions of existing games and others set in new worlds altogether. The rules were not only new in the GW sense – tweaked variations on a pre-existing rule base – but really new, bringing into being approaches to tabletop gaming which hadn’t really been done before. Back in Britain, there were rumours of blood in the water, that GW was tottering and shedding staff in endless acrimony, ripe for a challenge.

Enter the Mongoose

Back then, Mongoose Publishing was one of many RPG-focused publishers working out of the tabletop scene in the UK. Founded in 2001, and finding early major success with the Slayer’s Guides, Mongoose was a company with a rapidly growing reputation in the scene. In the early days, the majority of the creative output was in splatbooks for D20 systems, riding the diversity of DnD 3rd ed all the way to a comfortable niche. By 2003, the company was moving into the board and miniatures spaces, with Judge Dredd and Babylon 5 games on the horizon, driven by an ambition to become a serious contender to the supposedly-tottering GW; an ambition held in the mind of one man, Matt Sprange.

Sprange had founded Mongoose back in 2001 with his business partner, Alex Fennell. Carving out that splatbook niche – 36 “Quintessential” character class books, and 28 Slayers Guides for DnD alone – had solidified Matt’s Mongoose as a mid-level game publisher with a strong employee base and a wealth of publishing experience. As the 00s wore on, and with the steady business of RPGs to provide backing capital, expansion into miniatures came to be an increasingly important part of the business plan. The Mongoose offices dripped with minis, not just those commissioned by and for Mongoose games but also the ubiquitous GW, indie metals, and Rackham’s Confrontation. Lunchbreaks were mini game breaks, and the idea of developing something quick and simple to play – but still loaded with the breadth and depth of GW’s offer – began to emerge as a serious consideration for Mongoose. What that would be, how it would play and most importantly what it would be about was still up for grabs. As time went on Mongoose leadership were talking more and more about challenging or competing with GW even – and here’s the holy grail so many have reached for – making the fabled “40k killer”. As GW was doing so well with LOTR, perhaps another movie could provide the catalyst needed to siphon off a chunk of their prominence.

He talked a lot about Games Workshop. He chose the name Mongoose because he saw GW as a snake, and mongooses kill snakes, right?

Ex-Mongoose employee

Mongoose leadership didn’t want to topple the golden throne but grab at that market share that GW had so successfully crowbarred open and if, along the way, it got as big and as popular as 40k? Well, no bad thing there, eh? Starship Troopers certainly had potential. Insectile aliens vs Imperial Guard, satire and a loosely built world with plenty of room for players to carve out their own niches, big bugs, power armour, guns, psychic powers and explosions. Hell it wasn’t just potentially 40k, between the movie, cartoon and book it more or less was 40k, or at least a version that could have been had 2nd edition chosen a different narrative and thematic path. The IP had everything Mongoose were looking for, and plans for both an RPG and the miniatures game were set into motion. With a phone call to Sony, the licence was secured and the game was on.

The Day After Tomorrow

The Starship Troopers franchise itself started out with a half-novel-half-Platonist-diatribe cranked out by Robert Heinlein when procrastinating from finishing Stranger in a Strange Land. Ever since release, it’s more talked about than read, a middling military SF of humans in powered armour (admittedly, the armour is cool) shooting up Bugs and Skinnies, going through boot camp and idolising Heinlein’s self-insert moralist, later played by the glorious Michael Ironside, in flashbacks extolling the virtues of proving citizenship through service to a libertarian-fash state. It’s not a bad novel, and still stands head and shoulders above many of its contemporaries, and is, if anything, lighter on the weirder sides of Heinlein’s life and politics than some of his other books. The dedication – “to drill sergeants everywhere who have laboured to make men out of boys” – speaks to the kind of priapic military-worship it desperately tries to engender.

Paul Verhoeven and Ed Neumeier gave Starship Troopers the twist it deserved, making an ostensibly serious recruiting advert for a fascist future, and selling it as straight as possible to the extent where people still don’t get the satire. Doogie Howser dressed as a Gestapo agent. Aryan supermodels dying in the dirt killing enemies they couldn’t possibly understand. Michael Ironside spouting SERVICE MAKES YOU A CITIZEN! Four years later, at the beginning of our own forever war that accelerated the split between military worshipping paranoiacs and, well, everyone else, you couldn’t have got it made. People didn’t get it then, and barely get it now. Verhoeven got away with it in a period of massive tumult and turnover for Sony, leaving them with a fairly popular scifi movie (with great bugs) that seemed to either be dumb entertainment, a satirical masterpiece, a fascist rally, or somehow all three. What do you do with something like that, once you’ve got permission from Heinlein’s estate to take it to Hollywood? Why, you license the crap out of it, of course!

The details of this license are sketchy and hard to come by. For all that it was a tongue in cheek Sci-Fi Triumph of the Will, the 1997 movie had launched with the typical late 90s ranges of toys (damn those Micromachines are tight) and other tie-ins in a move that would now be consciously ironic, but back then was just another way of getting at that Jurassic Park clutter dollar. A fairly well received animated series followed in 99, providing much of the expanded universe that Mongoose would use, but after 8 short months, it too was gone. After a fallow period with only a pretty good RTS to break up the silence, by 04 it seems Starship Troopers was a license Sony was happy to ship out without much input on the finished product. The direct to DVD sequel to the OG movie, “Heroes of the Federation,” had vanished on release in 04 like a particularly large shit in a deep, clean toilet, shot in 36 days and produced on a shoestring budget. In my mind it’s very possible that “Heroes” was an attempt to produce something, anything, to keep the license in Sony’s hands – something that would bode poorly for Mongoose.

Nevertheless, it seems Sony were keen to get the universe out there, and 03-04 saw numerous Starship Troopers franchises taking shape. You might be unfortunate enough to have played the FPS, managing to just about do in 2005 what Kiss: Psycho Circus had, for some god-unbeknownst reason, done in 2000. Mongoose, with a license for an RPG and a Tabletop game, was one of several companies playing around in this space – but the only one to end up with a product worth buying.

Come on you Apes! Do you want to live forever?

In Mongoose HQ, the long term plan was for a deep lineup of miniatures to support a skirmish game on the scale of 4th edition 40k, perhaps somewhere between 40 and 60 models on the table. A skirmish/mass battle rule set, space for several launch ranges and an infinite scope to expand beyond the book, films and cartoon. Big on ambition, and with a massive initial release, it was by a quantum leap above and beyond anything Mongoose had put out before. All energies were focused on the sheer balls-out aggression of the release schedule. Attention had to be not just grabbed away from 40k, but won, wrested, the crown wrenched off and firmly affixed to the Mobile Infantry and Arachnids quickly, before it became just another game on an increasingly crowded scene.

We aimed to release something new each and every month thereafter, so people could get excited about the line

Matt Sprange

For an all too brief moment, it worked.

In context, the big box is still one of the best release boxes for any system, ever. Flat out, no argument. This was full on professional levels of publishing – something that until this point, no-one but GW was really doing. It’s worth breaking down the contents:

- Rulebook including full army lists

- 20 Arachnid Warriors

- 2 squads of 8 Mobile Infantry Cap Troops

- Templates, cutouts and standins

- Cardboard bunker terrain

The plastics were high quality, multipart and – in the case of the (animated series inspired) MI – included excellent detail, full weapons options and the infamous clear orange visors. The bugs were (and remain) pretty fantastic with a huge degree of posability, so the full chittering, chaotic swarm of the movies could be represented beautifully on the tabletop.

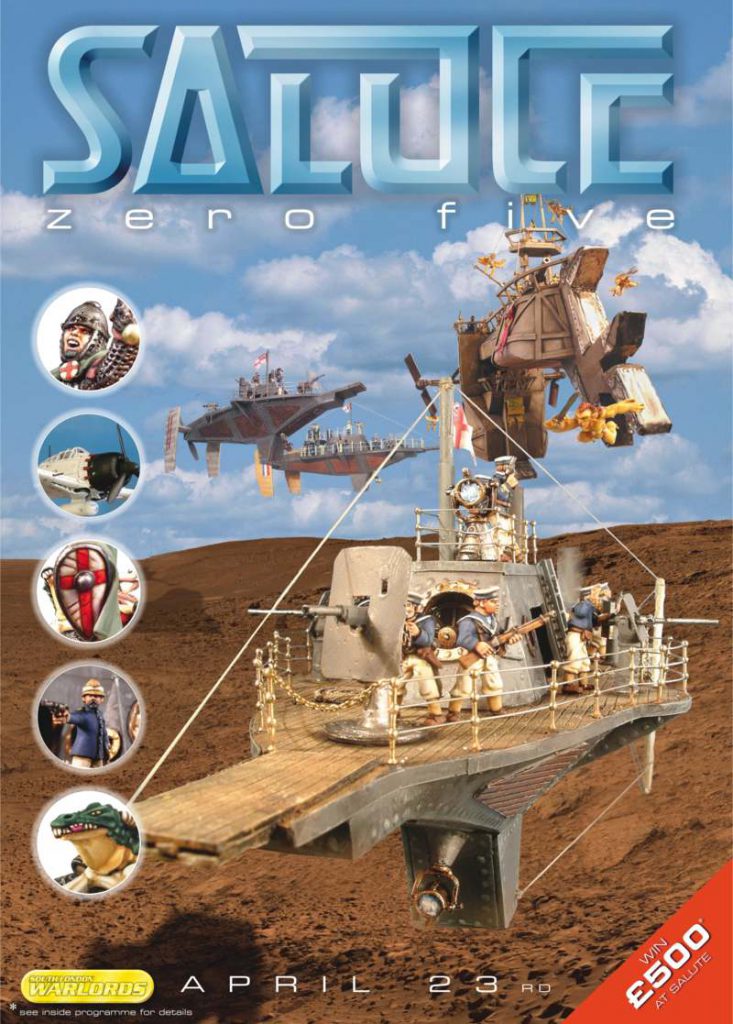

Sprange describes SST “getting snapped up” on release – a hell of an understatement. After previews at conventions in 2004, the full release hit the ground running. At Salute 2005 the crowds were near to fighting over the sprues, with tossed out templates from those purchasing multiple littering the floor. Mongoose had brought some pre-release metal walkers (classic early-mid 00s kits, big chunks of pewter), MI characters, and flame bugs along to the convention, all proving hugely popular. A 2005 Origins award kicked off a wildly successful release.

Within a week of Salute, those starter sets were hitting the tables in wargames clubs around the UK. Between leaving West Kensington where Salute was then held and those first games being played, there was a tidal wave of buzz and press floating around internet 1.0 – that Starship Troopers was great, that the rules were fantastic, that the miniatures were movie-level props, that your mate had got a kit and you were all going to play it next week. And that was just the beginning – hot on the heels of the swarm was a massive, punishing release schedule that pushed Mongoose’s capability to (and perhaps beyond) the limit. Full ranges for the Mobile Infantry (including lines based on the movie, book, and animated series) and Arachnids were just the start – a third army in the Skinnies followed up quickly, and rumours began to circulate about plastic dropships, tactical fighters, an expansion on the movie’s Klendathu invasion, and army books for the Human faction(s), Bugs, and Skinnies. Mongoose loudly promised a full and long-supported range far, far into the future.

Everybody Drops, Everybody Fights

When the reviews came in, it was clear to everyone that there was a fantastic game here, something that was not just playable and interesting, but straight up fun. A lot of this was down to rules – clear, crisp, different, and written by Andy Chambers (teenage me was, and adult me still is, very excited by an Andy-written ruleset). Andy was fresh out of Games Workshop at the time, was pointed at the concepts at the core of the universe (all three of them) and went to design a game from the ground up. The stand out rules – the reactions, dice pools, and stat blocks – have cropped up more or less everywhere since, but at the time were new and exciting concepts. Your bugs would skitter forward when under fire, and your MI would sometimes get one last critical shot off before being torn to pieces. Firing and killing was simple and clear, and zone-based hit allocation made shooting choices impactful and meaningful. Universal special rules for weapons, action-based turns, dice results being misses, hits, and kills, and many other innovative rules gave it a granularity that works well at a skirmish scale without bogging down play with tables and rules clutter.

Something that still breaks my brain today is that you never rolled to hit. Your pieces are either trained soldiers or hyper-evolved bugs, so the initial hit roll, the “can you hit the broad side of the barn” roll, is abstracted out. You shot at an area, 3 inches for most weapons, or 6 for heavier, blast-style pieces. The more firepower you could put into that area, the more likely you were to clear it out altogether, and squads could lay down more than one area of fire. You roll for volume of shots – some will kill, others will give a solid hit that might lead to a kill, and others will ping off chitin, much to everyone’s horror. Units can react to fire in their own ways – often flinching back a couple of inches, letting you herd a swarm into a pile for a mortar strike. It’s a little fiddly at first to get your head around, but it really, really works.

So very many of the games of SST I played I have vivid memories of simply because the mechanics were so elegant that those great narrative situations just emerged through gameplay very naturally

Doug, Mongoose Infantry Lieutenant

The rules created a careful balance of guns and mobility vs swarms of bugs that appeared simple – and appeared to massively favour the Mobile Infantry – but consistently delivered balanced, tense experiences (provided you had equal forces – not something provided in the core box!) where each side would have to carefully consider tactical and strategic plays to get around the advantages of the opponent. Balancing those forces took some experience – but once you managed it, tense, emergent narrative battles were not just allowed but supported and facilitated by the core rules.

Designing Starship Troopers

The lead designer of Starship Troopers won’t need an introduction for most of you reading this. If you’ve played games in digital or tabletop form, if you’ve played 40k and Starcraft in particular, you’ve played an Andy Chambers game. In 2005 Andy was fresh out of Games Workshop, where he’d been one of the leading lights of the second generation of GW designers. Andy was not just a name on the books, an author given a first or second billing on 3rd edition 40k, Battlefleet Gothic and the best codex ever written, Codex Catachans, he was also a constant presence in White Dwarf. Sardonic eyebrow, power mullet, occasional transformation into Evil Lord Valrak, Andy was the younger guy who did the cool battle reports against your dads Rick Priestley and Jervis Johnson. More than that, for those of us who are old enough to remember, but young enough to think working for GW was obviously THE BEST JOB EVER, Andy was the face of the company. It’s hard to overstate the cachet Andy had in a certain segment of the tabletop world in the early 00s.

So it makes sense that when you’re looking for a writer – maybe a writer feeling a bit pissed about some of the decisions made at GW over the last few years and wanting to do something different – you reach out to Andy Chambers. It also means that when you’re writing about that game, you do the same thing. Andy was kind enough to answer some questions on the process of designing SST – so I’ll hand directly over to him.

How did you get involved with Starship Troopers?

When word got around that I was no longer with GW, Matt from Mongoose sought me ought via a

mutual friend, Alex Fennell, in 2004. I was a massive fan of the ST movie and of course like any

growing gamer nerd I had read Heinlein’s Starship Troopers so I understood the difference.

Heinlein, Verhoeven/Neumeier and Chronicles all have very very different ways of exploring the

concept of SST and the forces involved. What was working with all these sources like?

Happily we found a sort of happy middle ground with the Roughneck Chronicles, that took a lot from

the movie but also expanded on the universe with new worlds, bugs and gear for the MI. Just ignore

the last few where things get a bit crazy and it gave us masses to work with. With the movie so

relatively recent and with such strong imagery (and music!) it would have been mad to try to revert

things back to Heinlein’s rather more cerebral seminal work.

In the designers notes you say it’s the first wargame you designed “from scratch” – how did it feel,

starting with a blank slate and a license?

Fantastic to be honest. I was very comfortable with having an established universe to work from, but I

also had more than a decade of pent-up designer-y energy that previously had to be sent down very

certain narrow channels. With the ST miniatures game I was free to do absolutely anything I wanted,

it felt deliciously liberating. I’d spent more than a decade designing within the same space with asides

into Epic and BFG, so that had been three editions of 40K, plus Necromunda and Gorkamorka and

lots of Codexes and White Dwarf articles along the way.

Did you bring any of the game design elements with you from GW?

I consciously tried to leave as much of GW design behind as I could, although I was so thoroughly

steeped in it by that time I have to accept I brought some with me. I guess just the general concepts

of how you handle a battle game for tabletop forces was very GW in its conception in my head, I knew it would be about squads versus swarms and not so much individual characters, although

there would be some big armor suits and bugs, etc etc.

We’d done a lot with 40K game design (including some things we shouldn’t have), but certain

constraints were always inviolable – IGOUGO was the worst example, but also weapons and model

stats, using D6s for everything post-2nd, even how measuring and coherency worked etc. etc. The

truth is if it ain’t bust don’t ‘fix’ it and the real places 40K always got bust wasn’t in the core rules but

in the Codexes and supplemental material. Nonetheless I’d thought of a great many things I’d like to

try over those years, but they were too radical for 40K and its offshoots. A new game gave me a

chance to try them for the first time.

In terms of the game design, what worked best?

The dice pool methodology (and from that model stats) and the reactions* system. I’ve replicated and

riffed off both of those in several miniatures games I’ve designed since then.

What would you have done differently with hindsight?

Made it more approachable as a game, it’s kind of tough to learn and get going with it. These days I

try and think a lot more about how you start off playing and then opening up the game rather than

throwing everything at a player at once, I was just a bit too excitable to be doing not-40K at the time.

The then-unique elements of the game crop up much more commonly now – do you think SST changed game design?

I think all games tend to have an impact like that, games designers are natural magpies and they tend to gather shiny ideas and try to fit them into what they are doing. Makes me kinda proud when it happens to pan out into a move in overall design, but I’ve been…uh…inspired by plenty of other games over my career and I think as much of it comes from picking up on the way things are going as blazing some sort of trail.

What did you take forward from SST to your subsequent work?

That it’s really, really nice to change things up once in a while, and the notion I could design new

games unlike the ones (well maybe a bit like) I had done before. Really that my whole career at GW

wasn’t just a lucky fluke if you see what I mean.

I took the lesson that people will respond really positively to movie and show tie-ins, and that with the right narrative hooks they are more than happy to play asymmetric and even (gasp) non-competitive styles of games. This is not to say we didn’t do army lists and points values for ST, we did and I would never do a game without that kind of guidance, but the mythic force of ‘game balance’ was less important than having a good story.

Thanks Andy!

I’m from Buenos Aires and I say kill ’em all!

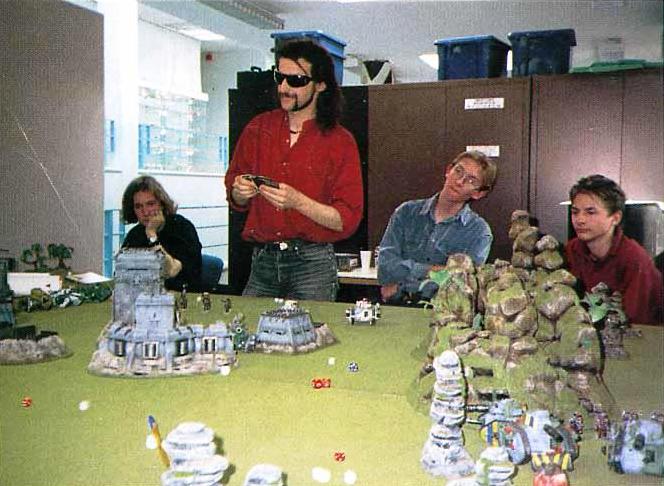

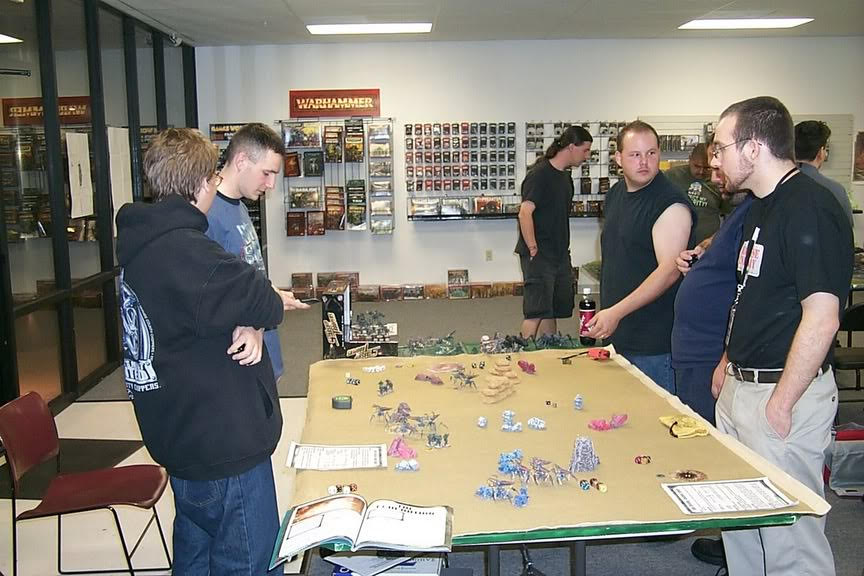

In support of the rules came the releases – Power Suits, multiple heavy walkers, Arachnids by the million and the well-regarded Klendathu Invasion source book – and a publicity push. Mongoose ran the “Mongoose Infantry” (MI) programme, putting representatives into LGSes around the world, relying on them to run campaigns, demo games, previews, and events. The MI programme got the game live in stores, pushing an alternative to Space Marines and showing off beautiful models. Doug (an MI Lieutenant) was instrumental to the writing of this article, and the genuine enthusiasm the MI had for the game, the above-and-beyond nature of their support still shines through, almost 20 years later. My first interaction with Starship Troopers was through an MI at a club night, and that scripted, managed game still sticks in my mind as a great experience.

Shepherded by a solid release schedule and great publisher support, by early-mid 2006 the game was at the height of its popularity. Thousands of starter sets had been sold, the metal range was large and growing, now accompanied by the Skinnies, book-inspired aliens with a tribal structure and high-tech weaponry. The MI had pushed the game into spaces and markets Mongoose couldn’t have reached without them. Anticipation for some promised kits was at a fever pitch, but release dates never quite arrived.

What was being released was (mostly) beautiful. The Tanker bug – standard, thorny and king variants – and the Plasma bug were standouts for the Arachnids. Pictures of them now slightly boggle the mind that anyone could have the sheer brass balls to release huge kits balanced on insect legs. The sculpts, while lacking a little compared to the modern day, were outstanding in their time, far above the S-dragon, the nearest plastic comparison. Other kits live long in infamy and anyone who has assembled the brain bug is truly a hero of the federation.

On the Human side, the mobile infantry suits ranged from Rogue Trader style goofiness to gorgeous hulking killing machines, with plenty of character models and multiple styles of infantry. The Marauder and Cougar exosuits were great, characterful releases with more variety in pose and positioning than comparable kits from other manufacturers (if anyone wants to chuck one my way I’d love a Marauder). The much-promised light mobile infantry (movie-style humans) in plastic never arrived, but Mongoose did release them in metal and they still hold up well today.

When it comes down to it though, the Mongoose SST mini releases come down to two plastic kits that together tell the story of the game in 2005-2007. One, the multipart plastic Arachnid warriors, are still fantastic models. They capture the movement, look and presence of the movie bugs, that ferocious, skittering and dangerous horde. They feel right and look sharp, all edges and chitin. They paint exceptionally well, letting you add freehand detail where you like, and even balance well on their pointy leg-feet-things in dynamic poses. They’re Starship Troopers done exactly right, and were released in both the starter set and their own SKUs – boxes of 6 and 18 warriors. Even with the advent of 3d printing and numerous IP-skimming projects, they remain the best and most faithful adaptation of the movie bugs to the tabletop.

The other is the Viking Dropship. The Viking has a starring role in the movie, deploying Jonny Rico onto Klendathu, while the slimmer, faster Skyhook lifter picks up the remains of the Roughnecks from Planet P. It’s a cargo-lifter style vertical take off and landing ship, with a distinctive chunky profile and a solid SF aesthetic. It’s the Mobile part of the Mobile Infantry (movie version) and was a huge draw to hobbyists. Back in 2006, there just weren’t a huge number of large, flying SF vehicles in plastic. Forge World were cranking out resin kits, but the plastic Valkyrie was still years away. The Viking was an iconic part of the background, would have been a groundbreaker in the industry and a huge opportunity for Mongoose to put a nose ahead of the competition. It never happened. Despite being teased from 2005 onwards, the game was dead long before the release. Mongoose Infantry reps were bombarded with questions on when, how, if, even what materials the dropship would be made from, but no answers would ever come. The prototype would eventually be sent on to one loyal, patient fan, who just kept asking for his preorder, refusing all refunds until the Mongoose team just packed up their dropship and sent it on its way.

The non-release of the dropship became the most visible symbol that something was wrong with Starship Troopers, wrong enough that it was noticed, commented on, discussed at great length and picked apart in LGSs and online. By mid 2007, the game was on its last legs, and the dropship nowhere in sight. By early 2008 it would be dead. What exactly happened – both to the dropship and the game – will be covered in our tomorrow’s article, Starship Troopers: Fall.

We can sum up 2007 for Starship Troopers as; Better Game. Better Models. Same Great System

Matt Sprange, Mongoose Forums