It’s early 1998. Somewhere in north Derbyshire, a Gorkamorka campaign was in full swing, soundtracked by Enya’s Paint the Sky with Stars. Across the UK, there was a clear template for the early months of the year in tabletop households – a kid somewhere excitedly chopping into a plastic truck for their mob, and a parent somewhere listening to that bloody album. To this day, hearing Orinoco Flow brings me back to a very particular memory – shrink wrapped plastic, that new box smell, spilled polystyrene cement, and the first Games Workshop game I ever played.

1998 also saw the release of Digganob, Gorkamorka’s high water mark. In Part One, we looked at what created the game and eventually led to Badshag’s Ladz being joined by Grot Revolutionaries riding Cuttas and Big Luggas made out of spare bases, matches, and the occasional prized bit, individually ordered in the Lenton shop to the great exasperation of the staff working there. For this brief period, the game was in rude health. Two boxed sets – the original starter, with the twin mobs of boyz mounted in trucks and tracks, and Digganob – formed the backbone of the release, and month on month more metals, hybrid-metal plastic vehicles and a range of Gubbinz to stick on them fleshed it out. Special characters, rebel grots, mounted muties and a bizarre range of conversions and kitbashes were still fighting it out on tables all over the GW world. Sadly though, no matter the quality of the models, the game, or the Waaghs echoing around game stores, 1998 would be the final year of Gorkamorka. A game made under extreme time pressure, where top level execs had intervened to decide the path taken for the big Christmas release at near-zero notice, now had to stand on its own two feet, or die trying – and in the event, it died.

I always felt it was something we were bullied into doing given the circumstances

Rick Priestley

At the heart of the story of Gorkamorka is a Space Hulk. While Imperial techno archaeologists are busy studying some interesting pyramids with the support of their monitoring team aboard the starbase Eternal Vigilance, the vagaries of the warp spit out an Ork-infested Space Hulk straight at the planet Angelis. The impact is cataclysmic, creating a ten year nuclear winter and driving a deep gouge into the crust of the planet. Nothing would ever be the same again. In many ways the trajectory of Gorkamorka follows its story, a nice piece of ludonarrative harmony operating at a financial and strategic level. Andy and Gav’s “rush job” game, the game that Sales Directors had fought bitterly for and was supposed to be grist to the mill of the company VISION, is the Hulk. Games Workshop is the planet. Part one of this article led us into the world of the studio, hearing from Andy, Nick, Gav and Rick about the making of Gorkamorka. Part two takes us out of it, into the world of finance and business strategy. This isn’t a story about their efforts in bringing Gorkamorka into the world, but one about the consequences – human and financial – of a very certain corporate culture, one that bet big on Gorkamorka and got it wrong; essentially, part two of “What happened to Gorkamorka?” is the story of the hulk hitting the planet.

Earnin’ Teef

After that frenetically-paced development cycle, Gorkamorka had gone from an undercooked pitch in a sales meeting to a real game, and more importantly in Games Workshop’s eyes, a real product. Now the Sales Directors who’d demanded the game had to sell it. The majority of that sales activity, the vast majority, fell to staff on the front lines of the sales world in Games Workshop stores, independent retailers, mom and pop shops, and all the other places you could buy games in the late 90s.

Back then GW store staff were “Redshirts” both, I suspect, due to their distinctive uniform – Managers were in a different colour, leading to the much more unfortunate “Blackshirts” – and due to the way they were often treated at the time. Replaceable, sacrificial redshirts, as dispensable as in any away team that ever beamed down to a hostile planet like Angelis. When we talk about “Sales” in this article, it’ll be with the capital S. “Sales” is the director-led system operating in Games Workshop UK and internationally. It’s guys with job titles like Director, International Director, Regional Manager making decisions about target numbers in the tens of thousands and directing their subordinates to deliver 100-1000 sales at a time, not the little-s sales teams ringing up £40 starter sets for Christmas presents in November 1997. Sales made the bet that their disruption of the Studio/Sales status quo would pay off, sales had to work with that regardless.

I remember people boasting about the number of staff they fired, and the view was there was plenty more “red-shirts” to fill the gap

Nick Davis

There’s a very simple answer to how Gorkamorka sold: it didn’t. But that masks a much bigger, much more impactful story. To small-s sales staff in Games Workshop retail, Gorkamorka was well received. It did sell, both in a big rush at that first Christmas and then in a continuing flow as long as White Dwarf kept supporting it. It was a fun, silly, self-contained game with lots of random nonsense, the opportunity to shout WAAAAAGH, and a design philosophy of cool models and wacky conversions, and audiences ate it up. Frontline Games Workshop staff I talked to for this article don’t recall it struggling at all. But those weren’t the sales that the VISION was looking for. Flogging starter boxes out of Games Workshop stores was, in 1997, only a fragment of the overall sales figures. GW stores were a big factor in the sales mix, but the company had always sold to independent retailers too, and as they focused more on markets outside of the UK – where it was often difficult for them to establish a first-party GW presence – those trade accounts grew rapidly. By 1995 trade sales had overtaken GW’s own stores in terms of revenue, and as far as management was concerned the bubble would surely never, ever burst. In true Gordon Brown style the only trajectory was upwards, no bust, only boom.

What that meant for Gorkamorka was that it wasn’t enough to move units in GW’s own stores, at a comfortable but unremarkable pace. To meet the ambitious store growth numbers looked for (125% target year on year!), to grow that independent retailer slice, and even more importantly to crack markets where Games Workshop wasn’t well known enough to support multiple stores of their own, what was needed was market saturation, a product flying off the shelves and straining the very limits of production capacity, and that meant exploiting the opportunity to sell in every context possible.

Gorkamorka sold exceptionally well in some of those contexts, because it could be marketed as a fantastic – and well priced – Christmas present that everyone would want. Naturally it had a heavy “toys for boys” slant, because this is the 1990s, and that’s just how things went in Britain back then – a few short years later, an unremarkable chocolate bar would launch a huge advertising campaign in these blighted isles on the basis of “It’s not for girls.” If there’s one thing that marketing geniuses of the Blair era loved, it was telling half the population very firmly not to buy their products.

“Exceptionally well in some contexts” was one thing, but then the Sales targets were exceptionally high, and they weren’t much interested in context – especially when that context was “in our own stores.” Though the UK was still GW’s largest market, and well on its way to every halfway-notable market town having a GW store of its own, it wasn’t by much. In 1997 turnover in the UK was at £21,282,000, but “Continental” Europe was close behind, having grown by just under 30% to £20,265,000. That important European market was at the time concentrated in France, with minor input from Spain and Italy, but Gorkamorka was an opportunity to go full-throttle into the other major European countries, chiefly newly-reunited, very populous, economically-booming Germany; further afield in the US, Australasia, and “other,” sales lagged a long way behind, but as in Europe, Gorkamorka was intended to be the product to storm those beachheads.

The European aspect is key to this story, because it added significantly to the cost of producing Gorkamorka. You could crack the US and Canada and Australia in English, but if you wanted Italians and Germans and Portuguese to play your game, then ideally you wanted to print it in their languages. With this strategy in mind, translated versions spearheaded a sales effort to make this one the true breakthrough game, the one which would boost European sales to unheard of levels, because every major market would get Gorkamorka in its own language. The 1997 annual report had cautiously talked about multilingual support from the UK centre, until a territory was developed enough to release products in translation. That caution now went out the window – the time was now, the product was Gorkamorka. Perhaps they should have just waited 10 more years, by which point any European teenager who might have wanted to buy Gorkamorka would also be a fluent English speaker, and saved on the expense.

Games Workshop have shown they understand word processing by reusing the vast majority of their previous products… what’s added is either funny (and useless) or plays poorly (and this is serious).

We have trucks and tracks whose movement is so random there’s as much chance happening in the movement phase as in combat.

It’s funny, it’s chaotic, but it’s a little boring, no?

Backstab Magazine 1998, Translated from French by the author

The reception was not always warm, but although French magazines may have been unamused (and how wonderfully French that last sentence is, incidentally), Sales was already committed. Not only was Gorkamorka on its way to every corner of the earth, in more languages than ever before, it was even going to appear on the greatest console the world has ever known. A licence was granted to US-based developer Realtime Associates who, through publisher Ripcord Games, put together what would have been a pretty revolutionary pitch – a co-op online driving/shooting RPG for the Dreamcast, with cross-platform play to PC. The game was already well into development when Gorkamorka was finally quietly killed off, to the extent that the Windows version was still being worked on into 2001, where a tantalising alpha build shows us what could have been. I’m convinced I saw a Dreamcast build on display, even playable, at Games Day 2000, but it seems I’m the only one who remembers it. The details of the Dreamcast’s demise are eerily similar to the situation that emerged in the wake of Gorkamorka, and spelled the end of the digital version as surely as what follows killed the physical. For a Games Workshop still a little unsure about mass-appeal video games, this unprecedented approach was a clear indicator that Gorkamorka was believed – or perhaps hoped – to have serious unit-shifting selling power.

Back in the physical world, every market across the continent that could feasibly sell Gorkamorka was targeted on the micro and macro scale. Sales Directors for Europe, the US, and Australasia plotted near-exponential growth on the back of the great gamble. Every store in every market was crammed to the fullest possible extent, “as many copies as they’ll take” being the mantra that ruled over the Gorkamorka pitch, and this is something that everyone who worked in selling Gorkamorka remembers. It led to some crazy situations with toy shops, newsagents, and post offices suddenly overflowing with towering boxes of Orks, Cardboard Forts and Trucks, but the mantra kept repeating – as many copies as they’ll take, as many as they’ll take, and they’ll take them because we’ll make them an offer they’d be stupid to refuse. Sold on the promise, the sure promise, that someone – anyone! – would come and buy the boxes, because THIS was THE game that everyone wanted, the stakes were exceptionally high. Not just reputationally, but financially, because the promise to all those independent stores in all those markets around the world was a risky one – as many copies as they’ll take, sale or credit.

12 copies of Gorkamorka into “Tiny Mom N Pop Chess ‘n’ Games” and then 3 months later 11 copies would be returned for a credit note

Gav Thorpe

So while Gorkamorka sold, it didn’t sell enough. Independent stores, many of them in markets lacking a large teenage audience primed to buy the latest GW Christmas release, were left with piles of the things. I’m sure they all shifted some boxes, even when they didn’t really know what they’d ended up buying, but nothing like as many as they’d been promised they would. Happily for them, it mattered a bit because these unsellable products had taken up valuable space at Christmas, but luckily they were on sale or return and so they could get credit – or cash – back from Games Workshop, and didn’t they just?

Gorkamorka, on release, had sold more copies than Warhammer Fantasy had shifted for Christmas 1996. In a reasonable context, that would have been a fantastic result. This wasn’t a reasonable context though, and what could – perhaps should – have been a triumph of Sales setting the pace went sour almost immediately. Instead of the record-breaking, career making numbers Sales had gambled on, Gorkamorka was being returned, first in English language versions that could plausibly sell anyway due to GW’s absolute dominance back at home, but then in French, in German, in Spanish and in Italian. What the hell does a company do with a product that isn’t just not selling as well as it was meant to, but isn’t selling in multiple languages, multiple languages where the market isn’t developed enough to keep them in circulation, and where instead of having thousands of new happy third party retailers you have a bunch of creditors raging about the thousands of francs, deutschmarks, pesetas, and lire you owe them? Just like in Part One, where the question stopped being “Why did Gorkamorka die?” and started being “How did it happen at all?”, we’re back looking at something that shouldn’t have happened. You’ve developed a product that is, by any objective criteria, quite weird, and then managed to sell it anyway in numbers that should have been very impressive. However, you’ve bet the farm on numbers even bigger than that, and then to deliver on them you’ve gone double or nothing – don’t sell them five, sell them twenty, and sell them in French, and if it means they’ll take the things now then we’ll carry all the risk. It’s a daft position for a company to put itself in, a fanatical all-out assault on the entire global market at once built on the back of a boxed set you didn’t even know you were making in July. Why would you willingly do this? To answer that question, why Gorkamorka flooded the markets with all the economic devastation that entailed, we have to look squarely at the corporate culture that unleashed it.

Always Be Klosin’

I’m torturing a lot of metaphors today, but it’s worth thinking about that flood one a little more. There was a lot of dammed up potential energy in that Sales vs Studio showdown covered in part one. To look at it from a Sales perspective, the company demanded revenue and further demanded that that revenue grow at an incredible rate – and who was on the block for delivering it? Certainly not the Design Studio. It was their necks, their reputation and their target the VISION was concerned with. Perhaps – I don’t know – there were conversations about “just what we could do if….” or “if not for X we could have done Y….” Perhaps it had even been flat-out stated that things would be different if Sales called the shots. I don’t know. What is clear is that, given their head, and given the backing of key members of the executive, Gorkamorka was THE time for Sales to go ahead and do their thing. If not with a product they had demanded, then when? Unleashed, undammed, a raging torrent of sales targets sweeping all before it, and careering straight for disaster. When something like this happens, it’s the culture of an organisation that precipitates it. It’s resoundingly clear that GW’s corporate culture was fully committed to the bit.

Sales was, to a far greater extent than any other part of Games Workshop, driven by cold hard targets. Filtered down from on high, growth would be translated into units sold in determined markets. The Sales Directors for each territory would interpret centrally set turnover and revenue aims into X number of boxes of Y product, with Z tail and various degrees of caveat and condition. Whatever the conditions, or targets, were, with production firmly within GW corporate control, manufacturing and production was much less of a bottleneck than it had ever been. Clever manoeuvring paired with astute purchases of plastics tooling capability and distribution capacity presented GW with the freedom to make these kinds of plays, and the new possibilities opened up by the Bryan Ansell and Tom Kirby approach were the space for that freedom to grow and develop.

What developed out of that freedom seems to have been a relentless, high pressure sales culture. With the VISION demanding incredibly high sales, and not just raw sales numbers but continual year on year improvements in performance, Sales staff faced a massive amount of pressure. It could not have been a healthy environment to work in, and GW staff we talked to stressed how replaceable and expendable a single staff member could be. If you weren’t selling enough – just like Gorkamorka, that isn’t “selling well” that’s selling enough – then you were in a difficult position. “Enough” wasn’t always just numbers shifted, but also about attitude, markets, big sales and size of client, adherence to the plan, and even where you’d entered the Sales team from. Redshirts – those GW employees who’d come from the shop floor – were particularly vulnerable, quickly moved in and out of central Sales when the numbers weren’t quite enough. It was a tough environment that bred tough people – a Sales team that demanded a lot, ordinarily managed to deliver it, and knew their worth to the company. That culture, as it often does, ended up feeding on itself. The VISION demanded explosive, extraordinary growth, and Sales was the engine for that growth. Without Sales – without the hard-selling culture of Sales – the VISION couldn’t be delivered, and the heads of the subsidiary Sales teams knew it. Empowered by Kirby and Prentice since the flotation in 1994, by ’97 Sales knew exactly what they could do within the structure of the company and – importantly – that the company relied on them to deliver on their targets. Without them, GW would face catastrophe, shareholders wouldn’t get their dividend and the VISION couldn’t be translated to reality. That meant that the culture of Sales at the time was unassailable, for good or ill.

I remember several Sales and Retail managers saying they could do without the Studio

Nick Davis

Even with all that, you’d think that someone would have spoken truth to power about the targets, the sales push, and the incredibly risky play it was to bet it all on the Christmas ’97 release of a weird game about Orks in the desert. It’s very possible that someone did, someone who I didn’t reach out to – didn’t even know about – when writing this article. That’s possible, but if they did they would have run smack into the biggest barrier to questioning the VISION that Games Workshop possessed: a slim volume amounting to the second most didactic book in its colour I’ve ever read – The Little Red Book.

Da Uvver Book

The Little Red Book (or Black Book depending on your edition) postdates our story by a few years, but it’s a telling document that gives a snapshot of the prevailing culture that led to the Gorkamorka incident. We’re not going to dive in to it page by page because, come on, this is supposed to be about Orks, but it’s telling that when making notes on it for this article, my first one is “Why the FUCK does it start with a quote from Uncle Tom’s Cabin?”.

The Book is a corporate culture guide cum style bible cum history lesson that speaks to exactly the kind of corporate culture that ends up with massive piles of unsold stock because someone who’d read it and knew exactly what it meant for his job to do anything else said “yes, of course, that’s definitely achievable” to the guy who wrote it. Inside the book, we’ll find gems about how GW isn’t a business but “a big loving family… sometimes we squabble, but we all root for one another”, and that, as a FTSE-listed public company, “we are still a little business”, at the same time as “poor fit means no job” and exhortations against “moral relaxation”. Other areas are a very uncomfortable read – when talking about those dastardly insiders who might harm Games Workshop with their (unspecified) acts and (undetermined) attitudes, it asks “Which of us would not shoot the traitor? Which of us would not shun the heretic?”. As much as anything else, it’s a one-man psychodrama, the kind of book you can read and easily imagine its author delivering in a continuous rant with the tone shifting wildly from moment to moment. The conflict that led to Gorkamorka and the rotting piles of unsold stock is right here on the page – “in a clash between the culture of a business and the nature of a member of staff, only the member of staff will get hurt”.

For all that it is couched in half-jokey 40k-style language, it isn’t a pleasant read and it can’t have been pleasant to receive one, knowing that you would very much be expected to adhere to the philosophy therein. You can feel the dismissal of other viewpoints and the monolithic do-it-our-way-or-leave attitude seeping out of the 59 pages. Even writing about it, I want to dive into hyperbole because reading it is so strange and so out of the normal bounds of what you’d expect from official material at a major corporation that it feels like it deserves it. But to match the tone of the book – alternately bombastic and light, sometimes direct and sometimes filled with veiled allusions – would be wrong. This isn’t a funny artefact of a weird time in GW’s history, it’s a record of a way of running a business, and that means that it affected how people – people who loved their hobby and wanted more than anything to work in it – lived their lives. If you talk to staff members at any level of late 90s to early 00s GW, you may hear about bullying, dismissals, a difficult work environment, and disregard for the wellbeing of staff. There are as many stories of burnout coming out of GW in the period as there are stories about Space Marines, and all of that, ultimately, comes out of the culture outlined in the Book. Everything that would lead to Gorkamorka is here, because the Book is written as a defence of that culture, and the VISION is the manifestation of that culture as formal strategy. If you’re in a company like this, where corporate culture has been enshrined, however jokingly, as something to be defended even unto death, where you are repeatedly told that “fit” is more important than “skill” and even the author of this document describes it as “a bit religious in flavour”, what can you say when confronted with a plan for selling Gorkamorka that has escalated beyond all reason? Is there even an avenue to talk about it?

Isn’t it ironic that you know for sure that someone uttering the words “I know my rights!” is someone who has just behaved in a completely irresponsible manner?

The Black Book

This was the key for me that unlocked the why and how of Gorkamorka’s disastrous impact. Not only was standing up against prevailing wisdom difficult, it’s hinted that this will end your employment with GW. More than that, the culture is a “family”, which is a code for unprofessional if ever I’ve heard one, so you might find yourself in incredibly acrimonious circumstances, or be pushed out due to “bad fit”. When you go up against the executive, even as the head of the Design Studio, that is “bad fit”. When you’re doing anything other than delivering the sales that will fulfill the VISION, that is “bad fit.”

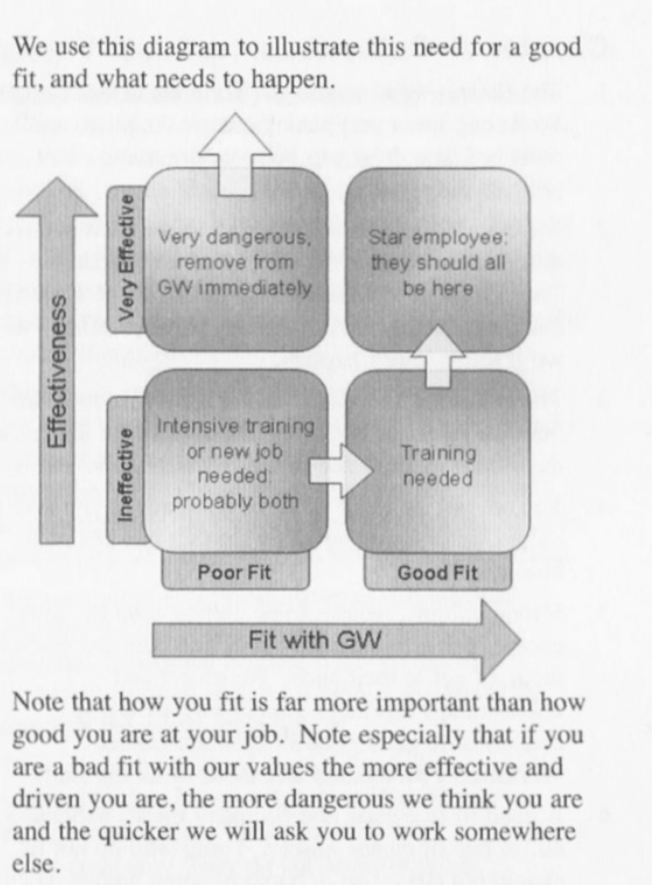

If you’ve worked in a corporate environment before, you’ll probably be familiar with a diagram that’s in the Book (and which we’ve reproduced below); two axes, one of which is “effectiveness” and one of which is “motivation,” and four boxes. In a normal environment, your analysis here is about flight risks – your best employees are the ones in the top right box (high motivation, high effectiveness), while the weakest are in the bottom left box (low motivation, low effectiveness). The ones you’re most interested in are in the top left, low motivation, high effectiveness box, where you’re worried they are strong performers you might not retain, and your goal is to find ways to move them over to the right.

In the Black Book, those people are not a valuable resource you are trying to keep hold of, because the axis is not “motivation,” it’s “fit,” and if you are high performance and low fit you are a threat. The wording in the diagram is stark: “Very dangerous, remove from GW immediately.” The paragraph below continues, “Note that how you fit is far more important [emphasis ours] than how good you are at your job. Note especially that if you are a bad fit with our values the more effective and driven you are, the more dangerous we think you are and the quicker we will ask you to work somewhere else.”

The book is filled with stuff like this, interspersed in the Black Book version with three separate Harry Potter quotes (no, you haven’t had some kind of shock, we are still talking about a corporate handbook routinely given out to managers), but that one page very succinctly summarises the rotten culture which gets us to Gorkamorka. The decree from the very highest level is that the business is run based on fit, not capability, and if people are highly capable but don’t fit, your job is not to find a way to get the best out of them or motivate them, it’s to get rid of them as fast as possible. This isn’t a culture that values challenge and questioning, it’s one that values everyone saying “yes boss” and doing their best not to be the one holding the bag when things go wrong.

When things do inevitably go wrong, and you’re the one unlucky enough to be a “bad fit,” there’s no one around to take responsibility because that’s not in the book either. Everything is personal responsibility – YOUR failure to sell a million quid’s worth of Gorkamorka, YOUR failure to ensure your store is profitable – while the company and the VISION are inviolate. It could be that a very difficult situation emerged – No-one will take learning and development from this, approach the strategy differently or learn to push back when management demands don’t match up with reality; it was your fault, and now you’re gone, and the heretic is cast out so everything will be fine now. There’s nothing in there about the executive’s failure to back up the Design Studio when a carefully worked-out plan is tossed aside at late notice for a half-formed thought which is expected to become a game in two months instead of two years, or how the VISION might have contributed to near financial disaster back in 98/99, because the VISION cannot fail, it can only be failed.

The standard here is excellence. 10 out of 10 every time, the best. And YES we do expect blood!

The Black Book

When it clicked for me was when reading the very end, after slogging through the entire thing, when the book compares itself to Wittgenstein’s lecture notes on linguistic philosophy:

Let’s end by reminding what was said in the introduction about the great philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. He was especially obsessed with how we know things, and he ended up writing an essay known as the Blue Book. He then stopped philosophising altogether as he had solved all the problems. What a guy! If anyone, having read the Blue Book disagreed with Wittgenstein or wanted to argue or wanted further explanation, he just said “Read the Book Again”

Gorkamorka must be a success, selling millions and fuelling growth, because that’s what was in the VISION, and the VISION didn’t bend to reality, reality had to bend to the VISION. Game didn’t sell because markets weren’t ready to go that big? Read the book again. Sales targets unachievable and bonus culture incentivised and primed to pursue them regardless of sale-or-return? Read the book again. Rushed to complete a job you’re not professionally proud of, to make a product nobody bought? Read the book again. It’s all in the plan, after all. With this at the helm, it’s surprising that anything went right, let alone that selling Gorkamorka, after a string of well-to-middle selling games, went wrong.

Night of da Big Choppa

So we have a game that isn’t selling, a culture that went all in on a risky proposition, and a company bible that could have been written by Ayn Rand tripping on fungus beer. By mid ’98 when the Gorkamorka Hulk had impacted and the nuclear winter began, the situation at GWHQ turned. Suddenly, Games Workshop had major debts. Suddenly, instead of year on year growth as they’d had since flotation, pre-tax profits stalled between 1997-99. Suddenly they had mounds of unsold – unsellable – stock, much of it expensively translated, tied up in impossible to part out sealed boxed sets. Most worryingly of all for the VISION, while growth in some of the least saturated European markets had been good, it slowed down to a crawl compared to previous years, all because that wellspring of independent retailers was now used up – goodwill burnt, credit note in hand, and a justifiable wariness about massive orders.

When a company, particularly a company with large and very wealthy shareholders, boards of directors, and massive growth potential sees that growth slow and that cash start to dry up, there’s only a couple of ways it can go. GW had made some big gambles on that growth and a disastrous Q1+2 in 1998 left them threatened with contracting sales that could cover the cost of business – just about – but not deliver growth. Some of their major shareholders even started to question the business practice. More than that, they’d built an investment plan based on costly actions like securing their own plastics supplier and guaranteed shareholder backing with a history of fat dividends. GW always paid out, except this time they were threatening not to.

It’s important to remember that when it comes to accounting there’s always a time lag; a set of accounts is a historical, backwards-looking document compiled after the fact, so the financial impact of an event and the steps taken to mitigate it don’t show up for a couple of years. First came some caution on investment, perhaps a little cutting back on high cost low yield products like new plastics for niche games, or the niche games themselves. By the time the 1999 Annual Report was compiled those actions to cut costs and drag GW out of the hole Gorkamorka had blasted into their finances were getting bigger, costlier, and more difficult. When your biggest cost is staff, what follows is an old story of the three Rs – restructures, reorganisations, and redundancies.

It was a major set-back that no doubt cost many people their jobs because we had to restructure to survive

Rick Priestley

People don’t want to talk about redundancies that much, particularly when they’re getting on to 25 years ago and they’re still working in the gaming industry, and fair play to them. It must have been a difficult time, and a personally very difficult time for many of the people involved. We can investigate it at a remove by going to the 2000 Annual Report from GW PLC to trace the shape of the restructure that followed Gorkamorka. There we can see, albeit couched in the most neutral business language imaginable, what happened, but all the while we should bear in mind the culture these occurred in – “good fit” was all, and every staff member was a resource that could be spent in pursuit of the VISION.

2000 sees the company returning to consistent growth after a slowdown, with the impact of those three Rs starting to tell in the finances. Restructuring becomes a key highlight of the year, that both production and sales had been restructured to deliver “more effective control of logistics and support functions” and “more focus on marketing the Hobby”. The Chairman’s statement outlined that the restructure, already 6 months old, was forecast to take up to another 18 months, really significant amounts of time in a business that had only floated in 1994. The restructure was costly – and remember that this is reporting on 1999 sales, when all those credit notes started to have a major impact – and growth in key markets had slowed, even contracting in the UK when compared to blockbuster numbers in 97 and 98. Attempts to shore up that growth in the UK and continental Europe hadn’t worked, and in the 2000 annual report Chairman’s Preamble, there’s a dark note that “loose talk” had begun to “question the health of the Games Workshop Hobby”.

By our own standards this has been a disappointing year but… we are taking radical action to address the position

Tom Kirby, Chairman’s Statement Annual Report 2000

One major attempt to dig up out of the hole was through a Board restructure in June 1999. Five directors of GW PLC were out, including old hands Rick Priestley and John Stallard, and new directors brought in. The old directors didn’t leave – instead they were moved over to Games Workshop International LTD, so not so much an exit as a redeployment. Still involved, but not on the board making the biggest decisions, which remained within GW PLC. Senior management was restructured around Operations and Executive and populated by external candidates bringing expertise, skills, and corporate experience, replacing positions that had been brought up through the slow expansion of GW through the late 70s and 80s. None of that was cheap, and Directors’ emoluments – already pretty significant – got higher, in addition to termination payments in the range of £100,000-120,000 for some directors.

Other reshuffles and reorganisations followed. It’s difficult to get details, for obvious reasons, but there’s a telling line in the Annual Report – that the reorganisation cost £1.3 million in “Property and People costs”. Some of that will be relocations, moving the Studio firmly into the main Lenton complex, but how much of it was redundancy, settlements and terminations? How much of it was about ensuring that “bad fit” employees at whatever level were shuffled out with a cash settlement? I don’t know – but surely some of it went to these cases, and behind that £1.3 million are undoubtedly sad tales of people who loved their hobby or their job or both paying for the mistakes made over Gorkamorka.

It’s hardly surprising that in some ways we were running to catch up, and occasionally we’d fall over or smack into an obstacle we hadn’t seen

Rick Priestley

The other major restructure was in the Studio. They suffered redundancies too, losing a dozen staff in the production and packaging arm as those areas were streamlined into a single, controllable pipeline. The Studio had been growing more or less organically since day one, and this was clearly a shock to the system. GW management were now firmly involved in the Studio – deciding who worked there and who didn’t, and deciding on the games that would be made. As you will recall from Part One the prevailing wisdom was that the Studio designed and Sales sold, and the initial discussion of what games would be developed was in-house, for Rick to decide and establish with the rest of the Directors. No more. The Studio would become a pitchfest based around those Easter releases, batting ideas up to Sales who would kill, or encourage, ideas based on what they thought could be sold. It might not seem like much, but this is a seismic change. It didn’t kill off the Gorkamorka-style boxed game – Battlefleet Gothic and Mordheim were both developed in this environment – but it did kill off the autonomy. Design would pitch to Sales, and Sales would decide the output from now on. In this new way of doing things, Gorkamorka must have become a totemic word to be avoided – there would and could be no follow up in years to come. What was needed, possibly even demanded, though the awareness that it was coming long preceded Gorkamorka, was a new sure-fire hit guaranteed to do everything Gorkamorka didn’t manage: Third Edition 40k.

What worked when we were a dozen people in a small factory in Newark didn’t work so well when we were a multinational company… [with] chains of shops all over the world

Rick Priestley

Doc’s Serjery

The thing with all this is that in the context of keeping GW profitable for shareholders, it worked. Just like a Mekboy replacing your Spanna’s brain with a bitey squig, it might not be what you want, it might not be moral, or good, or particularly sensible, but it worked, just about. GW’s losses, restructure, the use and abuse of Studio and retailer goodwill (and the careers of god knows how many GW employees) as fuel for the growth engine spooling up in Lenton – none of it cratered the company.

It came as close to major disaster as it ever has before or since, though. There was a sustained stock slump in 98-99 that shows both the impact of the restructure and the flickering, faltering VISION on investor confidence. An Independent investment column paints a fairly dire picture of a short term slump associated with the “stock problems” of warehouses of unsellable Gorkamorka.

Yesterday the sky fell in, with a profits warning caused by the strong pound, temporary stock problems and disruption caused by a move to new premises.

Andrew Yates, Independent Newspaper Investment Column

That 1998 hit was big, taking 70 million off the valuation of GW PLC. If you’d sold a couple of hundred thousand shares at the right time you’d made some significant bank, but if you’d waited until the wider world found out about the problems assailing GW at the time, you were now looking at several years of growth on the stock market wiped out altogether. The misselling of Gorkamorka isn’t solely responsible for all this, because the slide had already started before it all happened. What Gorkamorka definitely didn’t do is help GW cope with the slump – there was no giant profitable sale going on for Christmas 97 and into 98, no boar-mounted cavalry riding to the rescue. Instead, there were stock problems and product returns, boxes of Gorkamorka sent back from that global market they’d just tried to crack with a note attached that said “Erstattung, bitte.” Just as GW needed ready cash, to calm investors and remind the market their fundamental business was sound, it was all disappearing into a big pit filled with Orks.

The slump would last all the way through to December 2001, when a certain Ring-associated release started the climb out of it, and during all this time investor confidence was wavering. By the end of September Chris Prentice, CEO when Gorkamorka was being designed and sold, had resigned. The new CEO would get his shot at fixing the mess left by the Hulk, and in the culture of Games Workshop at this time, there was only one name in the hat to fill the post – Tom Kirby. The promise was that things would be different, and that a “revitalised” GW would soon emerge, one where a new book would guide the masses through the wasteland. A new method – Sales driven, of course, and really rather much the one that had gotten everyone here in the first place – would restore the stock price to the dizzy heights it had reached before the Orks.

A disastrous run of form for the group, which has seen its shares dive-bomb more than 86% since May 1998

Laurence Fletcher, City AM

We know the story of GW as it picks up in the 00s to now and it’s a story of two periods of massive growth, one fuelled by an outside force and the other of their own making. A lot of that is down to the choices and directions made in this period, choices and directions that gave us Gorkamorka and the resulting towers of boxes on sale or return. The enduring lesson for those in charge seems to have been control. We’ve mentioned vertical integration, sales strategies and market penetration and that’s obviously about control – a single strategy that determines how you make, market and sell your product, even to the extent of buying up the plastics producers that give you the raw materials that let you make it.

The clash with the Studio that left Andy holding the bag to put out a game in eight weeks is control too. Games Workshop was in the business of selling miniatures, and it was, under the VISION, inconceivable that anyone other than growth-oriented corporate management could possibly dictate what miniatures would be made. It might say “Games” in the company name, but Ansell and then Kirby’s GW was not about creating rules, but creating miniatures that sold, and that meant that if Sales said they wanted something, it would happen. The clash with the Studio was inevitable in a corporate culture that saw the game designers not as a leading part of the company but as a means to an end and prized devotion to the VISION over anything else. That’s control, and Gorkamorka provided not just the framework for asserting it but the perfect excuse to consolidate it forever. Once someone has seized control away from you, it’s almost impossibly difficult to take it back.

Another key part of that control seems to have become a permanent part of GW’s business strategy. After Gorkamorka, the lesson that has stuck around is perhaps that debt – any debt, even “good” debt you take on to expand and invest – is not a road they want to go down. GW plc is a cash business, operating almost entirely on revenue from year to year, and they’ve done very well out of it. It’s almost impossible to conceive of a modern multinational company, which turns over hundreds of millions of pounds a year, with a world-wide distribution network and a vast and increasingly lucrative IP, being run on income alone. In the modern, financialised business world everyone has debt; it’s what fuels the grab at the next big market segment, the thing that lets you scale up, no matter how big the business – but not GW. In their most recent half-yearly report, they had zero debt and were sat on £85m of cash, an inconceivable position for basically any other business of their size; did someone look at 98 and 99 and simply say “never again”?

Gorkamorka didn’t nearly kill GW, but it did kill a version of GW, perhaps providing the smokescreen needed to dispense with autonomy, with design-focused business practice, and to refocus the company around what the senior management were planning anyway. It gave a reason to do “back to the wall” restructures, shedding both people and patterns of work. Gorkamorka didn’t kill GW, it just pushed a bit harder on the brakes when they were already slowing down, and during that slowdown control was once and finally consolidated in the hands it had been drawn towards since the buyout in ’91. Regardless of what happened to Gorkamorka, exactly the same actions would be taken in the future every single time. Remember that the VISION can’t fail, it could only be failed – if you don’t get why, Read the Book Again. Perhaps even after all the other echoes of the Hulk’s impact had died away, all the redundancies finalised and the executive board renewed, even after Brian Nelson’s blister-packed metals had been replaced with finecast and clamshells, that is the single enduring legacy of Gorkamorka. Where, once upon a time, Design designed and Sales sold, now and ever after, Design designed after Sales had approved.

Dark Futures

What the failure of Gorkamorka – no, the failure of the VISION – did to the company perhaps goes some way to explain how much it has been airbrushed out of GW history. Gorkamorka didn’t sell enough, but it still found its way into plenty of eager hands, and it remains enduringly, if slightly bafflingly, popular. It never received a follow up, either as a second edition (as Necromunda did in 2003), or even in the short-lived GW Specialist Games section of the website. The rules were uploaded as PDFs for a while, but not to the extent or duration that Mordheim or Inquisitor were. In fact, when Rick argued his way into setting up the Specialist Games wing in the 00s, Gorkamorka was the only 90-00s specialist game that received nothing at all in Fanatic Magazine. Even the notoriously light-touch GW forums (yes, GW used to have forums!) had Gorkamorka discussion moderated out. Was it embarrassment that the Sales intervention had nearly cratered the company? Did someone on high airbrush Gorkamorka out of history like Nikolai Yezhov – covering their tracks by pretending nothing had ever happened?

That doesn’t mean that Gorkamorka was forgotten about, or that it became an unspeakable blight on the system. For what it was – a six-month game about Orks bashed together by Andy and Gav from Necromunda and whatever plastic kits were in the pipeline – it was, and remains, extremely influential.

Gorkamorka was a stepping stone to several new directions for Games Workshop, and not just financially. Gav, Andy, Nick, and Rick, who had all worked on the game to some extent, moved on to bigger things as a result. For Rick, Gorkamorka was a spur to set up the Specialist Games wing of GW after leaving the Studio, ensuring that no matter the financial strategy, GW long had a space for the niche, the exploratory, and the interesting. For Gav, Digganob was his first big solo project and in talking to him you can still hear the pride and challenge that taking on that opportunity entailed. Gav would go on to author dozens of codexes, editions of 40k, 50 published stories for the Black Library (and counting!) and what must amount to hundreds of White Dwarf articles. He says it “set the course of my career” and didn’t it just? It was a much less positive experience for Andy – the rush, the pressure, the whole attitude to the Studio must have sat poorly, and I can’t help but think it’s a step in the direction that leads us to his exit from GW, and the wider pastures we’ve already discussed in this series. For Nick, the experience led eventually to moving around GW and finally off and out to work on his own projects as a writer and artist with his company Alt World Studios. All four were involved in the next big project – Warhammer 40k – and given the time pressures on the studio, would have moved on very quickly. Lessons learned, and now applied to rejuvenate GW’s flagship franchise.

While the 3rd edition of 40k was developed and released in the context of GW needing a product to rescue them from the hole, it took a surprisingly large amount of creative direction from the brief shining light that was Gorkamorka. Both figuratively – in the lower-tech grittier and grimier galaxy that 3rd edition presented – and literally in the liberal reuse of art and art styles in the 3rd ed rulebook, the visual language of Gorkamorka seeps through in the look of its bigger, older cousin. Warhammer 40k had, of course, been in development alongside those early stages of Gorkamorka, releasing in October 1998, and it would have been well into the production cycle by the time Digganob was released, so this is perhaps more of a current that lifts all boats than a Gorkamorka inspiring 40k situation. If you have it, though, look at the Big Black Book, and then again at Da Roolz and Uvver Book in Gorkamorka. For all that 40k has many, many armies, there’s quite a lot of art in that 3rd edition tome of Orks hanging off buggies and trakks, of Slavers and grots and Scorchas and Nobs. Most of it is by Alex Boyd, Wayne England, and John Wigley, and most of it comes straight from Gorkamorka. The Grim Dark future begins in 2nd edition 40k, but it gets a turbo-boost straight from Angelis in 3rd edition, firmly entrenching the grey and black vibe of the 40k universe that would rule aesthetically through to the days of 6th and 7th.

Fittingly it’s for the Orks that Gorkamorka had one of its most significant influences over the 40k we know today. Prior to Gorkamorka the Orks had a much brighter, higher-tech, comical background, with some decidedly uncomfortable elements. The comedy of Shokk Attack Guns and the brightly coloured vehicles like Spleenrippas and Lungbustas rolled up against Stahlhelm-equipped Grots and outright fascist Stormboyz. It makes a kind of sense for Orks as football hooligans to be fash aligned as so many football firms were back in one of the UK’s many, many, bad old days – but both sides of the coin no longer aligned with GW’s direction. Gorkamorka allowed for a reset of what Orks could look like, and both the art and Brian Nelson’s superbly realised Orks provided a new, much more brutal (and much more kunnin’) look for everyone’s favourite 40k faction. Without Gorkamorka there’d be no Ironjawz or Mega Ghazkull and it was only in Age of Sigmar Dominion – released in 2021 – that Games Workshop moved even slightly out of the design space created by those Gorkamorka sculpts.

The Brian Nelson look continues to be definitive to this day

Gav Thorpe

The release defined Orks to the extent that the models released in the core Gorkamorka box have only just gone away. Ork Codexes going all the way forward to the release of the 8th edition version in 2018 featured the old Trakk and buggy kits, and even occasionally the Rokkit buggy metal and plastic hybrid made for Gorkamorka. Until Assault on Black Reach (2008), the Digganob special character Dregmek Blitzkart was the only Deffkopter model GW made, and until January 2022 he was the only one you could buy outside of a Patrol box. Even the Trukk, the much maligned tiny Trukk that the 3rd edition plastic Orks dwarfed to a comedic degree, could be bought as part of the Build+Paint kits until 2020. Those models, rushed into production, squeezed into a game because they were what was being produced anyway and something had to fill that Christmas gap, outlasted not only the design team that made the game, but the corporate culture that forced it. Plastic, after all, sticks around.

Other sculpts haven’t lasted as long, but they provide an interesting legacy of the route untaken. Paul Muller’s Diggas are intriguing sculpts filled with character and little touches, very much the scavenging Ork-wannabes of the fluff. Paul and Trish Morrison collaborated on the Muties, with Trish then, as now, the absolute master of the gribbly monster, and they’re very clearly degraded Imperial mutants, armed with plasma weapons and lasguns jury rigged after hundreds or perhaps thousands of years after the Hulk brought their civilisation crashing down. Both are a place that GW has barely touched until very recently, but their design has echoes of the Lost and the Damned and the xenos-cult of the Genestealers both of which have seen recent revivals, so perhaps even with these slightly less enduring sculpts there were lessons to be learned at Lenton.

For all that Gorkamorka was forgotten, killed like a Digga in the Mektown fighting pits, faint embers have flickered ever on beyond the reuse of art assets and model kits. Whenever GW reaches into its big bag of tricks looking for something fun in the endless darkness of the far future, it pulls out Gorkamorka. Gav’s Rebel Grots have become impossibly popular long after their context has disappeared. Da Red Gobbo – once the occasional scourge of the Angelis Desert – gets treatment that even the prime, universe-spanning characters don’t. He’s had a novel, Christmas cards, tree ornaments, multiple special edition models, and even a (now recalled) plush toy squig. The latest fun Ork model, the Goff Rocker, harks back to a much, much older design, but check his tour schedule – Angelis is on it. Even the Necrons have a soft spot for the game, and the in-universe explanation for what happened to Gorkamorka is that it ended up in Trazyn the Infinite’s collection. Gorkamorka for all its faults is still fun, still anarchic, and still joyous, not just for the company who clearly still enjoy the occasional rummage around in the background, but for its legion of devoted fans.

Da Unnamed Gorkamorka Fan

So Gorkamorka is still very much alive. It is still cared for – and still played. Various fan communities keep the flame alive, while multiple Facebook groups, Discord chats and subreddits keep fans discussing, converting and creating new rules for the game. These are fans with an Orkish fanaticism, that still hold out hope the Meks will give them janglies to book their place in the great Waagh. I put the question “Why Gorkamorka?” to the 3600 fans on the largest facebook Gorkamorka page, and within an hour I’d been deluged with replies. They speak to the enduring place Gorkamorka has in their hearts, not just as a historic oddity or even as a mark of how GW used to do things, but as a living, breathing game that offered and continues to offer something that people want to play. Their responses are varied, centering around fun, freedom, ludonarrative harmony with Orks and chaotic brawls, conversions and campaigns, everything that made Gorkamorka great, but one really hit the nail on the head for me.

Warhammer 40,000 is a franchise where the frenzied, zealous, space-catholic-fascists and their super eugenics space knights are the “heroes” by proxy of everyone else being utterly worse. It’s a miserable ‘world’, with darkness around every corner and a penchant for repaying hope with unrelenting, hideously traumatic violence.

Meanwhile Gorkamorka is a ‘world’ of Looney Toon esque antics, where you and your mates ‘ave a skrap over literal junk in the hope of becoming bigger, meaner, Greased Lightnings all for the purpose of getting a one-way-ticket to an EVEN BIGGER FIGHT. What’s not to like?

Jimbo Green, Gorkamorka Facebook Page

One of the brightest lights in the long dark since the death of Gorkamorka has been the site. You might know the one, it doesn’t have a name – the Unnamed Gorkamorka Site. TUGS has kept Gorkamorka going since the collapse of Geocities purged the web of the early days of GW fan sites, and holds on to a lineage stretching back to the earliest web 1.0 discussion boards. TUGS might have slowed down a little at times between 2009 and 2023, but it’s still there and still going. It’s also, amazingly, still going strong on the Gorkamorka url, which, if anything does, shows how forgotten Gorkamorka is over in Lenton – a fan site using the actual, full on name of a Games Workshop game? Can you imagine?

TUGS directs you to third parties for the bits and the vehicles and the terrain as much as it does GW, crawling the web for the shiniest gubbinz, the best Orks and the weirdest conversions to keep us all going for our quest for teef and janglies and to be da best dere eva wuz. Over on TUGS, the Gorkamorka Community Edition (GCE) is going strong, releasing the first core faction pack – Gorkers and Morkers – in September 2022. The GCE represents the future of Gorkamorka, far from the Design Studio and the Little Red Book, making much needed clarifications, updating the layout for a slightly less late-90s confusing approach and – shock horror – adding a glossary. The game mechanics are rewritten, updated, licensed under creative commons and open for you to play around with. The core “fan gangs”, some with a pedigree stretching back all the way to the Citadel Journal – Dust Rats, Feral Orks, even Dark Eldar – have added new and exciting elements to the game, picking up where GW so terminally left off in November 1998. The GCE means that Gorkamorka is still there, still living, and if scrapping for that one way ticket to the WAAGH interests you, you can, if you want, dive right in.

Da End

So where do we leave the story? If we stopped in 1999 or 2000, we’d be left with a company reeling, the 2nd generation of executives gone, cash reserves becoming perilously low and mounting debt repayments to cover both Gorkamorka and the vertical integration driving the VISION. You’d not write them off – the big pension funds owning their stocks certainly didn’t – but you’d perhaps be looking at those targets, and the restructure, and the new approach, and the early drafts of the little red book and everything else Gorkamorka kicked off, and wondering if it was viable in the long term. The outcome here could have been fairly disastrous, with the new strategy of Sales calling the shots and the design studio reduced from a creative engine to just another avenue for profit and growth generation tripping and falling on the first major hurdle. Not even, really, the first hurdle but the first time the new way had even been tested. The sales-focused executive had gambled and lost comprehensively on Gorkamorka, interfering with a long-standing and highly profitable way of doing things in search of the impossible growth targets, and not even come close to justifying it. But that’s the thing with these kinds of strategy shifts; the only failure state possible was complete and total destruction. The Red Book makes it clear that the plan was always – could only ever have been – to carry on regardless because the remaining leadership was so firmly behind the VISION it was incapable of doing anything else.

Perhaps Gorkamorka could have been the beginning of the end, and I’d be writing this as a curiosity piece about what was once the world’s biggest wargaming company on a website with a very different title. But I’m not, because even as the echoes of the engines and WAAAGHs and that shattering impact of the Hulk were still resounding in the corridors of (GW’s) power, and the courtyard of Warhammer world, there was a white rider on the horizon. In the dying days of the 3rd age New Line Cinema were shopping around for ways to shore up their own gamble, that a Kiwi schlock horror director could pull off the Lord of the Rings trilogy. When the licensing for a tabletop wargame version was pitched, Games Workshop were there and waiting. The Fellowship of the Ring hit cinemas in 2001 and Games Workshop’s vertical integration, global reach, and tightly controlled sales strategies were ideal for getting 25mm versions of Viggo Mortensen and Orlando Bloom into every shop, news agent, family home and gaming store. The LOTR bubble supercharged Games Workshop, easily doubling their revenues practically overnight, “justifying”, however retroactively, every decision made that had led to Gorkamorka. You could go so far as to say it justified everything – anything – because it’s then that GW explodes worldwide, whatever stats you can pull about shop growth and market penetration from earlier annual reports. The thing that saved the VISION, that GW would rely on their own properties and tight control of every element of the process, was, in the end, an outside force.

So what, then, of Gorkamorka? How can we think of it in its context when Gandalf et al were about to arrive and make all that fallout much, much less important? For the company at the time, it caused a huge upset that shaped how GW would operate in the future, much of it bought in acrimony and friction with the design team. It wasn’t the last specialist game – Inquisitor, Warmaster and Battlefleet Gothic would follow – or even the last big box side game – Mordheim, released soon after, remains popular to this day. In terms of its ethos and import within the company, it was the last of one way of doing business and the first of another. It’s a relic of a time when a single botched release, or even the struggle over what scale of miniature they’d release at Christmas, could worry the board enough to threaten the company. In a way, that’s the real legacy of Gorkamorka as the final representative of the version of Games Workshop before LOTR; from this point onwards the design team would pitch to sales, the exec would follow the VISION, and the stock price and the unfailingly reliable dividend would grow almost endlessly higher as the properties turned ever inward on 40k and Fantasy and mined Tolkein for all he was worth.

The version of GW that Gorkamorka brought into the world persisted for some time. The age of the VISION brought us through the millennium, a range of games and multiple editions of the core properties. Specialist Games didn’t even die away. Many of the most fondly remembered ones from the early years of the century would have at least been a twinkle in the studio’s eye when Gorkamorka was hitting the finances hard, and there’s a clear tail of these six-month supported games that brought us Mordheim and Battlefleet Gothic and Inquisitor. These games were launched and supported in a new way, largely collected under the Fanatic brand and Rick’s guidance, even, eventually, with their own spin-off design studio. All of those games were released in the post-Gorkamorka status quo, but no-one bet the farm on them in the same way; largely they existed in a twilight zone of patchwork ongoing support, still being sold but with no overall plan for how to keep expanding on them beyond the first six months unless it could fit in a White Dwarf article. Perhaps GW became more risk-averse, but once the LOTR money started coming in, it mattered less and less if a single side release struggled. It might not have been the beginning of the end of Specialist Games, but perhaps – as much as I’m loathe to quote Churchill – it was the end of the beginning. None of those futures, even the grimmest and darkest one, had any space for complicated skirmish games about Orks that created a wide open creative space for the players.

It’s important to note as we close that the version of GW that brought us the Book and the towers of unsold Gorkamorka isn’t the GW of today. In the modern day, GW is a different place with a different culture. While the transformation that started in the exec when Rick went to talk about Warmaster kicked off a long phase of GW’s history, it did eventually end. The last seismic leadership shift that completed the metamorphosis from Steve and Ian in their flat to the modern FTSE 250 behemoth strangling the competition happened in 2015. GW is a very different place now – different ways of operating, different cultures, different people, different books.

But Gorkamorka is evergreen, and not just because it’s about Orks. The impact it had on giving us the 40k that stands astride the miniature gaming scene like a giant effigy of a poorly understood Ork God was significant, and in directing and launching careers of key staff at GW, much of what came after was born out of those few Gorkamorka boxes. While there was no future then for Gorkamorka, that doesn’t mean there isn’t one now. Necromunda is back, and better supported than ever. Warmaster lives on in Warlord Games, an entire company thriving off Rick’s pitch back in 1996. Games Workshop is once again in the business of creating these kinds of niche games and Gorkamorka is, after all, green. Every year faithful fans await an announcement on 1st Orktober – only ten months to go, perhaps. Gork (or Mork) could be good to us yet.

Sources and Thanks

Thanks to everyone interviewed and interrogated for this article – thanks especially to Gav, Andy, Nick and Rick, and to the GW shop staff who told the story from the sharp end. None of this would have been possible without their honesty, transparency and willingness for me to bother them with questions. Thanks also to everyone at the Gorkamorka Facebook page, especially those quoted and to Kieran for pointing out the Revell kit partnership. Goonhammer writers Jackie, Lupe, and Condit were of great help. Thanks to Dylon for all the photos. Lenoon and Corrode thank each other.

All sources for the financial information for GW LTD and GW PLC, including quotes, are publicly available via Companies House and were sourced from there, without the input of the interviewees.