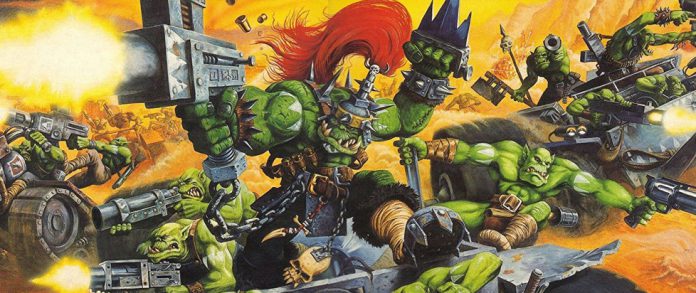

The first ever character I named was a Nob, much to the bemusement of my Dad. Ten year old me used a table at the back of the rulebook that came with it to innocently dub this Nob “Badshag”, and the bemusement tipped over into full on “what the Christ”. Badshag the Nob and his gang careened around a 4×4 bit of yellow painted chipboard precariously balanced on a kitchen table for a couple of years, constantly trashing my dad’s mob, made on kind sufferance. Badshag’s ladz endlessly grew in power, and mob rating, and teef, because I was ten, and I cheated.

When Gorkamorka went away, I never asked what happened, or why, because I was too busy playing it and having an absolute blast. By the time I noticed that there weren’t any more articles appearing in White Dwarf anymore, the game was long dead and buried.

Gorkamorka is probably the most short lived of what would become the “Specialist Games”. There are a lot of dead games out there, but Gorkamorka only lasted six months in the dying days of the second millennium. On its face that’s not much of a basis for an article, but it’s also a game I really liked. This article isn’t just about that, though; Gorkamorka is perhaps a little more important to the history of Games Workshop than some of the other boxed games that emerged in the late 90s and early 00s, even some of them that are around to this day. What remains interesting and important about the game is its end, and the rumours that surrounded it. That someone bet big on Gorkamorka, as big as the Hulk that brought Orks to Angelis. When that Hulk impacted, Games Workshop would be forever changed.

Unlike when we looked at Mongoose’ Starship Troopers, this is a story internal to GW. There’s no competitor here, nothing pushing GW to kill Gorkamorka from the outside. Their own internal pressures killed it, and went beyond, setting in motion some seismic changes. Gorkamorka was the herald of the end of an era, of a style, a business practice, and the start of something new and very different. Part One of this article will look at exactly what Gorkamorka was, how it came to be, and what we got out of it. Part two will look at the Hulk plummeting to Angelis, and the massive impact it had on the wargame landscape.

Da Roolz

For those of us who were solidly 90s kids, Gorkamorka isn’t (and perhaps never will be) the name of the Orruk God of destruction. Gorkamorka was a 40k spin off game, a weird, complicated, anarchic play experience set in the deserts of the Ork world Angelis, inhabited by gangs of truck and bike mounted gangs with names like Da Red Arrer Boyz, Da Spike Boyz and Burzuruk’s Bad Boyz. Written by the big names of the GW design team – Rick Priestley and Andy Chambers, plus an up and coming Gav Thorpe – it was light, fun, heavily randomised and all about your own ladz– Necromunda with a decidedly Orky twist.

At its heart, it was a narrative campaign system bolted onto a very granular classic 90s GW model. Gangs of 6-8 Orks divided into Kunninly Brutal Morkers and Brutally Kunnin Gorkers fought over the main campaign resource – scrap – while haring around the board on bikes, half tracks and trucks, getting blown up, shot, kicked off the side of moving vehicles, chopped to bits and then returning to Mektown for the campaign resolution. The rules, at all stages, were pretty complex and detail oriented. The classic GW statline and 40k 2nd edition DNA meant that granular detail was the order of the day, a far cry from the complex but semi-streamlined GW games we’re now used to. Fights were resolved via dice comparison, vehicles had individual hit locations with effects that would spiral into glorious, complicated chains of actions – skids, out of control slams into terrain, trucks spilling Orks all over the harsh desert sands.

The games were fast, a little silly, and the mechanics didn’t really slow the game down

Nick Davis

The rules governing your Orks, and later Diggas, Grots, and Muties, were all pure Necromunda with the slight Orkish slant that melee was significantly more effective and powerful than blasting away with a shoota or slugga. Where the game really broke away from its older, underhivier sibling was in the vehicles. Gorkamorka was all about vehicles, and the real innovation at the time was the emergent, out-of-player-control gameplay that arose from them. Orks being Orks, passing too close to an enemy vehicle could result in a chase, boarding action or ram. Vehicles moved with a push your luck system of gas (predictable, standard and controllable movement) and thrusters – literally just your drivers hitting a big red button marked Go Fasta. The vehicles themselves determined how big your Mob could be – everyone needed to physically fit onto a vehicle, be it truck, track, or bike, and there were no gameplay limits as to what your vehicles could look like. You were beholden entirely to your imagination.

That’s probably the main bit anyone around at the time remembers about Gorkamorka. As a player you were unleashed as a modeller, converter, or kitbasher in a way that no other Games Workshop game has ever allowed. The only rule was that you had to be clear whether something was a truck (faster and more manoeverable) or a track (better over the rough ground that formed a big slab of the terrain you’d use.) Double- or even triple-tiered trucks crammed with boys, full model sailing ships with wheels on for the rebel grots, and whatever other fever dream you could construct was the order of the day. Everyone in the studio, in the mail order team, and around the country went crazy for it. Badshag’s lads rode around in a double-decker truck festooned with bits of Imperial Titan (for some reason), and a frequent opponent in Sheffield mounted his gang in a heavily chopped up Rogue Trader Land Raider.

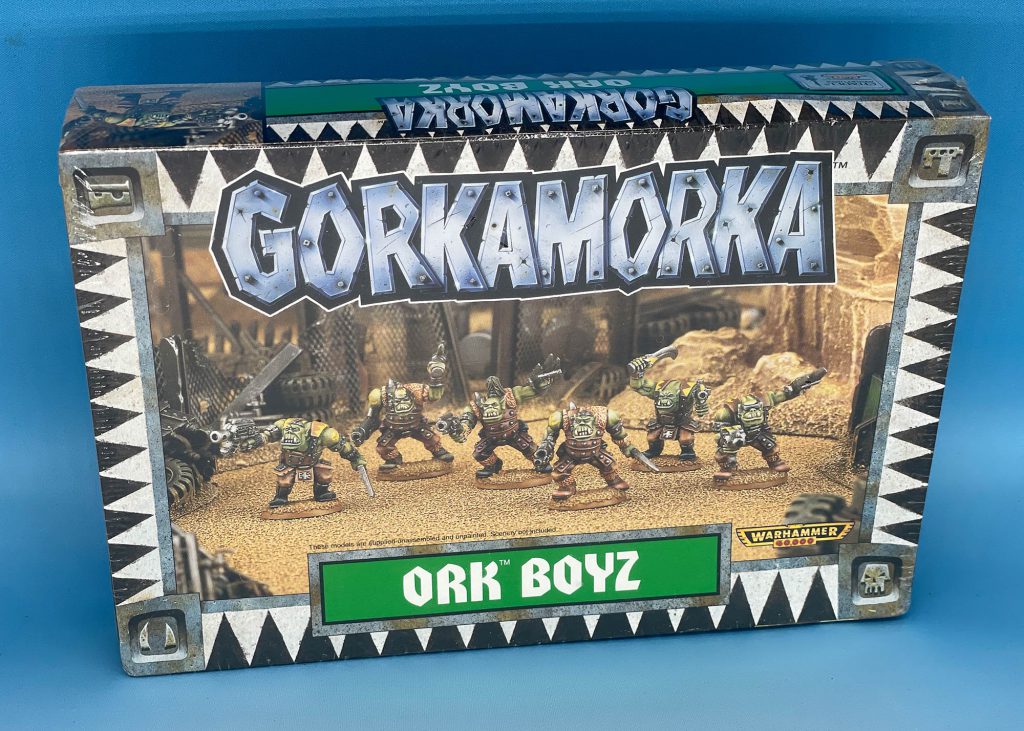

That focus on conversions supported a great range of metal and plastic kits. The release box, a classic example of GW’s £40 big box releases, had two complete gangs based on the only plastic kits Gorkamorka would receive – a brand new Ork Boyz sprue (not remembered particularly fondly!), two half tracks, and two trucks. The old stalwart Ork Buggy and Bike kits complimented the new lads on the block, but the real advance in Gorkamorka came from the metals. There, the full force of Brian Nelson, the greatest sculptor of Orks (and Orcs) GW would ever have, was unleashed. Brian brought a new vicious and savage look to the Ork kits, moving them firmly away from the cartoony, smiling lot of the Rogue Trader days into the hulking monsters we know and love today. Colin Dixon, another stalwart in the late 90s GW sculpting scene, brought his considerable skills to the range as well, giving us a delightful array of characterful, interesting boyz and vehicles. Colin and Brian’s Gorkamorka Orks meant business, and the Grots in particular remain absolutely classic, almost perfect, sculpts to this day. Though scale creep has hurt the boys, many of the metals still show up in Ork armies hitting the tables 25 years later, and rightly so – they’re just that good.

Those models found a new visual language for the Orks, one that we’ll return to in Part 2, but they weren’t the only thing in the box. Because this was the late 90s, GW also provided a huge amount of cardboard terrain – a massive Fort in the core box, a crashed starship and tents in Digganob and, on release, a watchtower in White Dwarf. Tank traps, barrels and assorted other battlefield gubbinz accompanied them, plastic terrain that would long outlast Gorkamorka and sold as the Battlefield Accessories Sprue all the way through into 7th edition 40k.

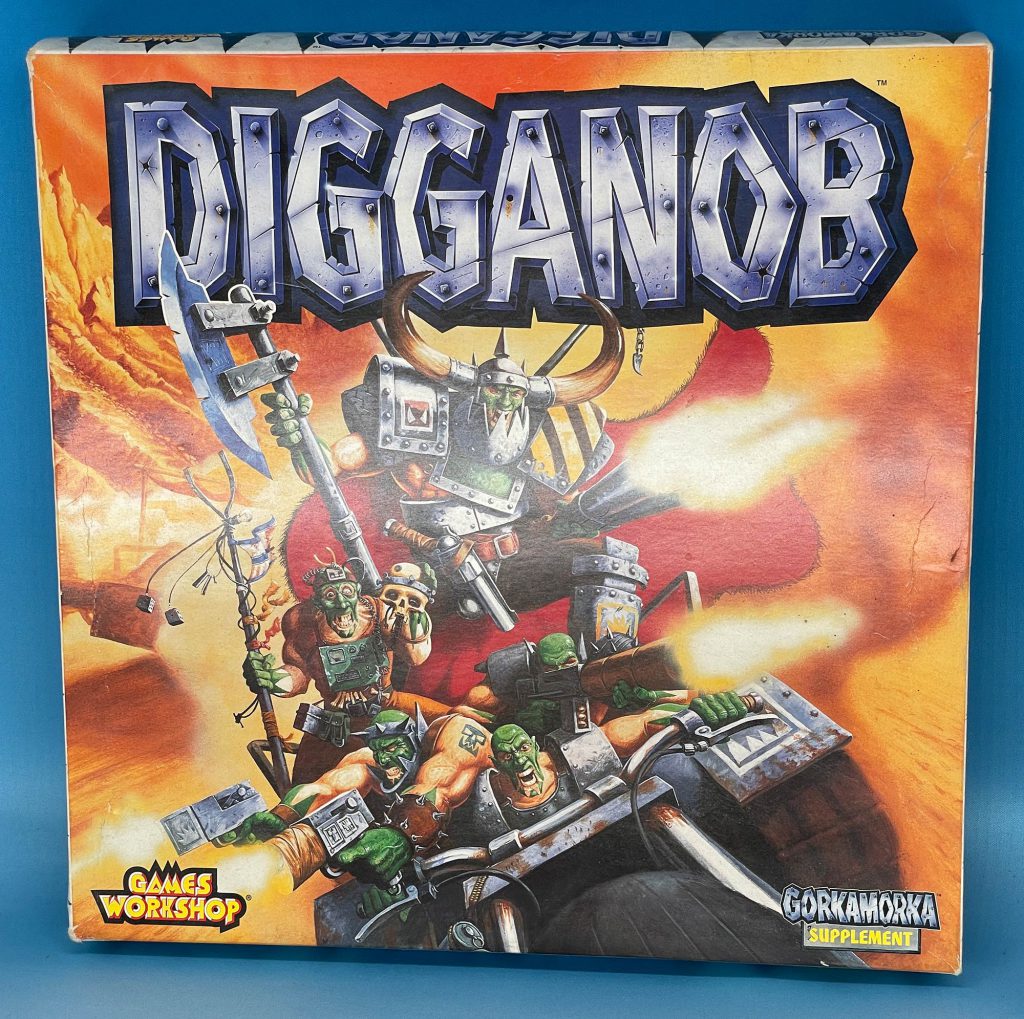

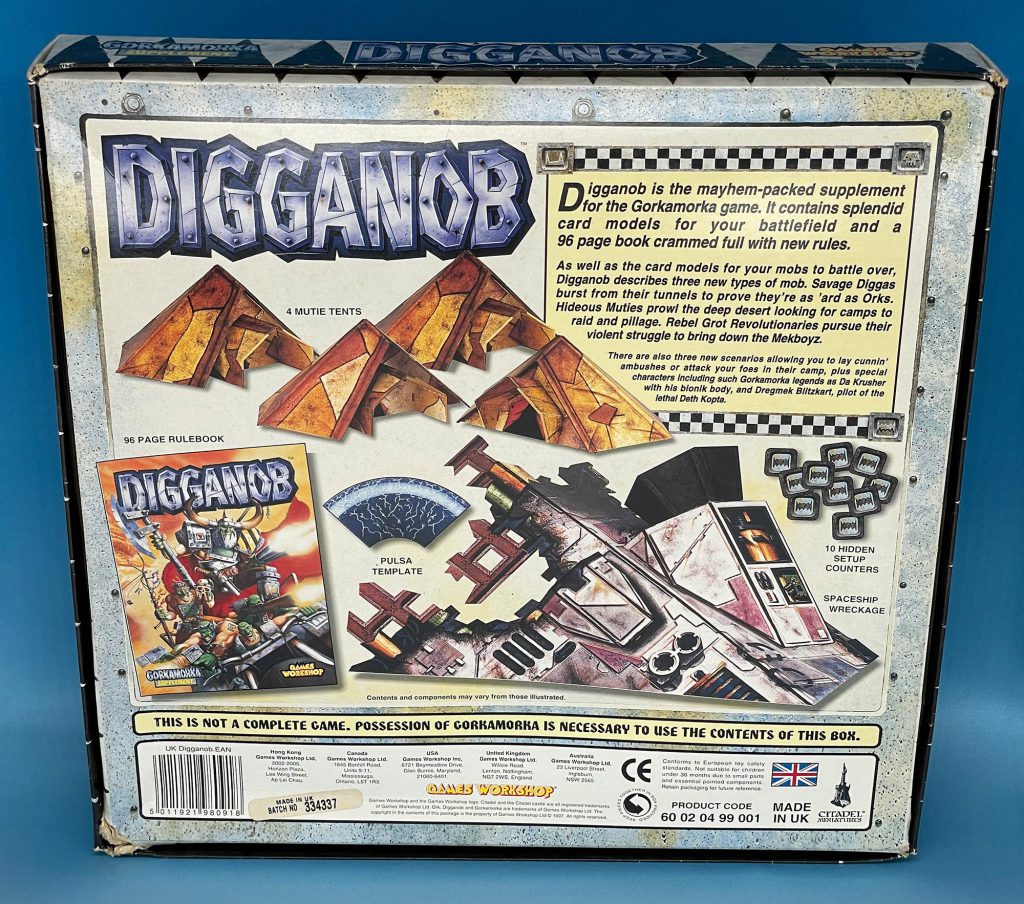

In February 1998 Gorkamorka got its first and only official expansion, this time penned by rising design star Gav Thorpe, that brought depth, variation, and some fantastically well-loved miniatures to the game. Digganob saw us learn about the Diggas – wannabe Ork humans, the first occurrence of Communist Hero Da Red Gobbo and da Komittee for Equal Rides, even the first solid look at the Necrons, who would ultimately give us the in-universe answer to what happened to Gorkamorka.

Trukks and buggies howled corkscrews across the display, ripping across the desert shanty town built around the enormous idol of Gork – or Mork.

Trazyn’s investigation had turned up mixed answers on exactly whom it represented.

The Infinite and the Divine, Robert Rath

Until Battlefleet Gothic: Armada was released in 2003, it’s arguable that Digganob was the best expansion box for any GW game. Others had added complexity to the games they supported – Warhammer Magic and 40k’s Dark Millennium adding so much that they fundamentally broke the editions they accompanied – but only Digganob radically changed the game for the better. Once Digganob had released, Gorkamorka was a five-gang game, complete with special characters, a wide range of scenarios, meaningfully different choices at gang level and a solid – if shaped entirely by random d6 and d66 rolls – campaign system, one that that supported narrative gaming in local groups, where rivalries, trading, archaeotech hunts and Grot raids rubbed up against the Squig brain transplants and intricate vehicle upgrade systems of the core book. Digganob represents the game at the peak of its powers, albeit not at the height of its popularity. It was, unfortunately, always going to be downhill from there.

Timeline

Perhaps suiting its focus on Orks and their world, the timeline of Gorkamorka’s demise is nasty, brutish and short. The initial release box came out in September/October 1997 just in time for Christmas, splashing into a big White Dwarf release where the hallowed magazine itself – for one issue only – was rechristened The White Ork. Content packed the next few issues – example games fought by designers Andy and Gav, Andy Kettlewell taking the reader through making your gang and a three-game campaign, extra scenarios, example conversions, Grand Warlord Adrian Wood’s terrain building masterclass and massive piles of mail order gubbinz you could buy from both Warhammer and 40k ranges for your mob. There was a clear wave of enthusiasm coming out of GW for this crazy, conversion-heavy skirmish narrative game, one that was felt very strongly in the prepubescent almost-hobbyist community I found myself in 36 miles north of Warhammer World.

The demo boards in the Sheffield store (still there on Fitzwilliam Gate) showing off the first wave hosted my earliest GW experiences, my intro to tabletop gaming. That Christmas was all about Gorkamorka in the store, with stacks of Ork Boyz being glued together by enthusiastic kids, and Gorker and Morker gangs beating seven shades of snakebite leather out of each other for the scrap that could win your boyz tickets to the great big Waagh. Badshag’s lads – and I suspect most of the fellow led-by-ten-year-olds gangs that I played against – grew preposterously ever more powerful, and all my pocket money went in to flicking through component lists and catalogues, cherry picking bits from 40k and fantasy to weld onto my trucks with the two part epoxy I was unwisely given as glue.

Christmas 1997 came and went, and February brought Digganob and a new range of Mutants, Ork-obsessed humans and Rebel Grots. Just three issues of White Dwarf – three months – after the release of Digganob, Gorkamorka slipped out of focus. The final time that Gorkamorka would appear as a supported game in White Dwarf was an advert on the back of WD 221, and a D66 table in WD227 – November 1998, a year after release. Gorkamorka, like all of what we might now think of as “specialist” or even “boxed” games back in the 90s, had a complicated half-supported life after White Dwarf. Under the auspices of GW’s Old Guard, all the classic games – Necromunda, Gorkamorka, Battlefleet Gothic, even Warhammer Quest – were given a brief injection of life via Fanatic Press. Gorkamorka got a single issue of a new magazine – “Gubbinz” – collecting White Dwarf and Citadel Journal articles published in 1999, and then nothing else. Even for the Fanatics, Gorkamorka was done.

When researching and interviewing people and bombarding ex-GW staff with questions, at first I found this pretty baffling. Why go through all that trouble to make games and support them with a range of models – plastics and metal – and all the glossy output that in the late 90s only GW was capable of doing, to see it wither and die in six months? The answer: that this was the whole point of these releases – didn’t at first make a lot of sense.

Itz not un-oosual

Games Workshop had a track record of releasing, supporting, and quietly dropping games throughout the 90s. Usually these received a big splash in White Dwarf, an initial wave of releases, an expansion box, articles and then…. gone. Blood Bowl (1993) had Deathzone (94 – though both reissued again shortly after Gorkamorka), Necromunda (1995) had Outlanders (1996), even Man O War (1993) had Plague Fleet (and Sea of Blood). Most recently prior to Gorkamorka – and highly relevant to the eventual fate of the game – 1997 saw the release of Epic 40,000 – the third edition of GW’s 40k-in-6mm. Six months of support – and a massive range of metal and plastic models – and then gone. Each one of these games, for all that they’re loved now, would be launched, supported with at least one major expansion, and then they would disappear from the shelves into the back catalogue and eventually even that access to the models would dry up. This was long before serious reprints – though Blood Bowl was a noticeable exception to this – and far in advance of GW making any rules for anything available online. Once a game was gone, only the Mail Order team (then still “fondly” named the Trolls) knew where it went.

This was a fairly concrete model for GW at the time. Release schedules, set in concert between the two powerbases of the company at the time, called for alternating releases of the big two – 40k and Fantasy – with side games, each one requiring a big box launch timed to coincide with a key release window like Christmas or Easter. Three months of consistent support, followed by slowly tapering content in White Dwarf and the Citadel Journal, was a reasonable commitment that allowed a burst of sales, some space to innovate around the core concept, and then some hype time for the next major release. Gorkamorka was a filler product, never intended to last beyond its launch window.

Given all that, the question of “What Happened to Gorkamorka?” suddenly felt very clear. It was released, it filled the Christmas sales gap, and then once it had done the job, it went to the big pile of Specialist games in the sky. So the question changed. Why, in the dying days of second edition 40k, did Gorkamorka even happen? A complicated, fairly difficult skirmish level game with entirely Ork-focused factions and a massive focus on conversions and where nearly everything you’d ever need was right there in the launch box. Necromunda, but with vehicles. No tie to 40k beyond that kits could be used in both games, provided you played Orks, and there wasn’t even a Space Marine in sight. The more I looked into it, the stranger it became. The question isn’t why Gorkamorka died, but why it happened at all.

Da Cycle

To answer that one, we need to understand who made Gorkamorka. There’s a simple answer to this and a slightly more complicated one. The simple answer is that the Design Studio made Gorkamorka – it was their job, after all, they made the games. The Design Studio was GW’s brain trust, responsible for producing not just Gorkamorka, but everything GW released at the time.

In 1997, the key figure of the Design Studio was Rick Priestley. Rick was in charge; in Gorkamorka terms, the Nob of the studio. Rick had been one of the key figures in the early days of GW, finding initial fame (if not fortune – yet) with Reaper, a skirmish fantasy game co-written with Richard Halliwell. Reaper brought Rick into contact with Brian Ansell and eventually Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone. Reaper led into Warhammer Fantasy, releasing in 1983 and almost immediately becoming the core of the then-nascent GW empire. By the time Warhammer hit its third edition in 1987, Rick was also writing Warhammer 40k: Rogue Trader and soon after became an Executive Director of the company. It’s important to remember that, because everything that follows might seem like a David vs Goliath situation, but it wasn’t. This isn’t about the little guy being squashed by the relentless march of capital, but two competing philosophies jostling for space, different really in their intent, not their kind – not David v Goliath, but, fittingly, Gork versus Mork.

Like the rest of Games Workshop, the Design Studio was going through a period of expansion in the late 90s, and with expansion came a furious pace of releases. Core game editions, Specialist Games, Codexes, Army Books, Campaign Supplements, weird side games using loads of cardboard in White Dwarf, even special Games Day scenarios all came out of the Design Studio – and always had. The Studio was growing, pulling in people from across the company with varying levels of expertise in game design, but all with the same enthusiasm, desire, and will to spend their days designing, testing, and fine tuning games. A mix of industry vets, young designers brought up through an apprenticeship programme, and long-time GW staff formed the core of the team, and they were held to a punishing release schedule to fuel the ever-growing need for content. The release output of the design team in 97 gives a good indicator of the pace of releases. Two Warhammer Army books. Rules for the Vyper, Falcon and Attack Bike (all, hilariously, still on sale). A worldwide campaign. Warhammer Fantasy 5th edition. Epic 40,000. Campaign boxes for Warhammer Fantasy. Gorkamorka.

We worked, you were worked, it was always busy

Nick Davis

The Design Studio had a wide ranging brief, mainly outlined by Rick working in a three year plan – imminent releases in year one, solid plans in year two and sketched out release schedules in year three. Every year, Rick would put designs in front of his fellow Execs, still at that time largely long-standing games design veterans. The plans would be discussed, and out of that discussion would come the plan for the next year. There’s a bit of an inbuilt tension there that I’m sure is obvious to even the most oblivious Grot. How long could the Studio remain autonomous when plans went through the executives dealing with sales, logistics, staffing, investment? Only as long as a rough balance existed between Rick as head design honcho and all the other execs. However tenuous it was, that was the situation as it existed in the late 90s. Once it had been checked off and approved – perhaps with a caveat or change, but usually minor amends at most, the plan went to the Design Studio, and then the work began. Design designed, sales sold. Once the studio knew what it wanted to make, it was off and running.

To design a game like Gorkamorka – or Epic, the other side game release in 1997 – you needed two things: lead designers and a full calendar year. The big release window was September so that the ubiquitous £40 box would be on everyone’s Christmas lists – and that meant work had to begin the previous summer. It took – and takes – a long time to get a GW game to market. Plastics came first, with initial designs in December and the final toolmaking process completed by April. Metals could come later, a simpler and quicker process being slightly more responsive to any changes coming down the pipeline. Printing, logistics, translation, White Dwarf support all cascaded into place 4-6 months before release and the final pieces of the puzzle were all sales related – by June, it was out of the Design Studio and into the wider company.

You needed a year to do a big box game properly – the best games tended to have two years lead-in time

Andy Chambers

The design process would kick off with some core concepts – scale, army size, theme – and once approved, a sign-up sheet would go up in the Studio offices for playtest and refinement. The culture of the Studio team at the time was towards mass involvement, core writers sparking ideas off the wider team, who would playtest, tweak and improve. Gorkamorka was characterised by a massive and widely popular playtesting phase, one “won” to some extent by Nick Davis’ Red Arrer Boyz who grew through painfully devastating losses and stonking victories to be the absolute top dogs of the studio campaign.

It was a conveyor belt of stuff going through Games Dev

Gav Thorpe

It wasn’t all playtest fun and riotous campaigns though. The pace of work in the studio was fierce and the pressure immense. Content was absolutely king, so there was never a break, never a point when the studio could vaguely rest. Even with Rick’s hand on the tiller, the studio was still worked hard and relentlessly. Whatever time was available had to be put to the task of making a new thing, or putting the final push on an upcoming product, or even pitching madly to fill those sketched out 2 and 3 year plans.

Rush Jobs and Last minute surprises were very, very commonplace at GW

Andy Chambers

Once you had the time frame, you needed the designers. Andy Chambers was the lead on many of the big projects coming out of the team at the time. Tuomas Pirinen, Nigel Stillman, Jervis Johnson, and many, many others – all still big names in games design to various extents – were key players in the expanding team. Side games were still led by the major players – Andy Chambers would get Gorkamorka – but they were also places where newer members of the team could make their name. Most relevant for Gorkamorka, this meant Gav Thorpe.

We know Gav from his consistent involvement in much of the 00s and 10s output of Games Workshop, from large releases like Inquisitor to the Path of the Eldar series and the Raven Guard and Dark Angels sections of the Horus Heresy. In 1997 though, Gav was a junior member of the team and Gorkamorka gave him the opportunity to fly solo – Gav was kind enough to talk to us about his involvement in Gorkamorka and the enthusiasm for his first solo effort comes across clearly, even 25 years later:

Digganob was quite a step forward in terms of career. I’d been writing WD articles for three years at that point, and I had finished my first Codex – the Sisters of Battle. Previously I had worked on two Warhammer Quest games supplements – the Pit Fighter and Catacombs of Terror – but that had mostly just been the words, not really any interaction with artists, miniatures designers, production and so forth. Digganob was me pretty much flying solo as a Games Developer. Not that I was abandoned – Andy, Rick and Jerv were on hand with advice and playtesting. But from the brief from Rick onwards I had quite a bit of latitude to develop the ideas for the extra gangs, their style and rules. I also had assistant games developers to boss around. I remember a specific conversation with Iain Compton about the mechanics of sailing vessels and how they don’t apply the same to land ships (for the Rebel Grotz vehicles). All-in-all it was about taking full responsibility for a project.

Thanks for that Gav!

Gorkamorka set Gav off on a trajectory that would have some pretty huge impacts for GW, ones we’ll return to in part 2, and his experience speaks to the collaborative (if time constrained) spirit of games development in the studio. While periods of work were stressful, some games were rushed and work expanded to fill all available space, the system and the time given to games development led to the regular release schedule of major and minor games that formed the backbone of GW’s offer. New releases kept coming, support kept ebbing and flowing, and the conveyor belt of games, rules, expansions and reissues kept on running. For a solid chunk of the 90s the Design Studio cranked out new editions of core games and created enduring spin off games that are still with us in one way or another today. Time pressure might have occasionally bitten, sales and design might have seen different paths forward, but Necromunda, Blood Bowl and Warhammer Quest were all produced in this context, and all continue to be sold (albeit with some interruptions) today. It was a stressful, but successful, environment working to clear deadlines and with the support of the wider company.

Gorkamorka was different.

I know the love for Gorkamorka is real, but I banged that out in eight weeks basically by heavily re-writing Necromunda

Andy Chambers, Reddit AMA

Kirby’s Dream Land

It really was different. Gorkamorka was a new way of doing business. But it wasn’t an unpredictable one, because smashing into the Brutally Kunnin’ world of the design studio was the Kunninly Brutal world of the Executive. Games Workshop was an ever larger fish in the pond back in the mid to late 90s and everything about the company was changing, and changing quickly. Those final years of the 2nd Millennium form a transition period between a company that was still blinking in the light of a stock flotation and international popularity and the relentless profit juggernaut of today, so we need a little GW history lesson to really understand why Badshag and his Ladz tore up a bit of chipboard in a Derbyshire garage in 1997.

Games Workshop had kicked off in 1975, when a couple of lads making wooden games in an upstairs room managed to somehow wangle the exclusive European distribution rights for a little game called Dungeons and Dragons, leading surprisingly rapidly into a UK-wide sales, design and distribution network for a wide range of gaming-and-nerdery related stuff. The company grew and grew, establishing Warhammer in 1983 and Warhammer 40k in 87, pulling in an ever wider crew of designers, miniature sculptors and painters and growing fairly haphazardly – even expanding across the pond to the US. In the late eighties, it was still more or less operating as it had in the late 1970s. Some guys, there forever, making decisions based on what they wanted to make, paint and play, on games they wanted to design, and ways they wanted to sell them – a business plan based on hard-won experience, but mainly, it seems, on vibes. But the company was growing internationally, and management burdens (design, sales, management, HR, accounting – all the stuff that you don’t really need to think about when you’re some dudes in a flat selling Gygax’s early work), were getting larger and larger. Professionalism – or at least an attempt at professionalism – loomed.

New staff, and new approaches from existing staff, started that process in the late 80s and early 90s. In the mid-80s Bryan Ansell, originally in charge of Citadel Miniatures, became group managing director of the entire company. Along with executive control came increasing shares in the company, first a minority stake in 1987 and then a majority one in 1989. At some point, someone must have thought it was time to hire some management staff without games design experience – perhaps “management experts” or some such – to bring in a decidedly non-vibe based approach. Tom Kirby was brought on first as Sales Manager then as General Manager; in 1991, he led a management buy-out which removed Ansell and also the last remaining shareholdings of original founders Livingstone and Jackson.

We also didn’t have a stand-out candidate to run the Games Workshop side of the business. We knew we needed Bryan, but then, Bryan needed us too. It wasn’t too hard to convince him to stay on by promising him we would back him when the time came for us to step down

Ian Livingstone, GW Founder, Dice Men

From the minute Ansell took over in 1985, GW’s plan for growth was based on their home made settings, younger audiences and controllable properties. For much of his time in charge of Citadel Miniatures, Ansell waged a long war to focus GW’s business on what his part of the business did, i.e. making and selling miniatures. When you’re coming from that manufacturing background, you know what you need to do to sell: control the manufacturing arm, make what you sell, and keep people buying it. The buyout sees the (partial) end of GW ever being at the whim of anyone else, focusing in on selling what Citadel was making. They own the retail, they own the advertising/magazines, they own the factories, and it all feeds off itself to keep customers within your closed ecosystem. At the time, GW simply wasn’t big enough, or integrated enough, to do it all, but with Ansell and then Kirby at the helm, the new, insular, approach was set. In the half-decade between Ansell taking charge and the 1991 buyout, the tone changed – much less large-guy-with-beard-and-pipe 1970s style fantasy, and a new focus on Warhammer and 40k. The vibes-based business was dying to a firmly management-oriented approach.

The board believes the Group will continue to grow, and is committed to increasing shareholder value

Brian North, GW Chairman, Annual Report 1994

By 1994 the new approach to the business led to a flotation via venture capitalists ECI Partners for a then astonishing £52 million (for those little guys? made of lead and that? those guys?). This is the age of Tom Kirby moving from Managing Director, Senior Executive Director and then finally Chairman of the whole kit and kaboodle. The aim was relentless, endless growth under his own particular (and peculiar) way of running the business. We’ll come back to this management style – and little Red Book – soon. But for now, it’s enough to say that the line was drawn – there was a new boss in town, and he had a new way of doing things. From a financial and business perspective, it worked, propelling GW from niche to a key portfolio piece for institutional investors. GW’s growth after the flotation was incredible – expansion across the world, new games, new premises (Warhammer World, as we know it now, comes from a 1997 consolidation to Lenton) and vertical integration, buying up tooling and printing and plastics injection firms, even plastics producers. GW was rapidly turning itself into the world-spanning behemoth we know and love (?) today. Though times certainly were different, once GW was settled like a hair squig into the always faintly sweat-smelling Lenton factory/castle courtyard, the major patterns and approaches were set in motion. There’s differences between now and then, but they’re differences in degree, not in kind. The seismic change can be charted in the Annual Reports to Investors, because once they’re in Lenton, they go from exactly what you’d expect from a company, you know, things like sensible formatting, a serious tone, black text on white pages, clear financial statements, etc to what you’d expect from a company under the Imperium of Man – giant Imperial Aquila, black glossy cover, quotes from Space Marines, bombastic promises, formatting like an Administratum employee had their final fatal embolism before Servitorisation. The company had VISION now and was careful to put that VISION front and foremost, integrating everything into one single plan to the extent that the design language in the 1998 Annual Report is the same as the 40k 3rd Edition rulebook released that year, and damn anyone who thinks that is weird (it is).

The board believes the Group will continue to grow, and is committed to increasing shareholder value

Brian North, GW Chairman, Annual Report 1996

The reports outlined a giant, endless, priapic thrust for growth, delivered in 90s business-speak to investors looking for a solid dividend return in an environment that apparently would only ever get better. This was true end-of-history venture capital and the transcendent dream of the executive acting with unlimited power and impunity of the kind you saw over the pond – just swapping in lead for silicon. The targets were ambitious to the point of insanity – 20% year on year expansion in store numbers, cracking open Europe, America, Japan and Hong Kong (still a British Colony and seen as a doorway for GW into Asia), translations into every major European language, virtually every plastics supplier and toolmaker in the Midlands bought and relocated to the ever more imposing Lenton facility, endless consolidation, streamlining, efficiencies, corporate cultures, every word you can imagine coming out of a fin-de-millennium exec. Expansion into international markets, so far cautious and tenuous, even bouncing off and out of a few – was now the major target. Increasingly, the money, the growth, the opportunities, the challenge, was coming in from overseas, and the markets showed rapid expansion, growing sometimes up to double their revenue base year on year. Growth powered the VISION, and the VISION was simple.

The march towards total global domination goes on

CJ Prentice, GW Chief Excecutive, Annual Report 1997

The VISION – a fully vertically integrated, international juggernaut that relentlessly seeks out every potential hobbyist and sells them a closed ecosystem of high-price, high-quality kits begins here. That meant the top dogs of the company had to change, and those hold outs from the old days and old ways, particularly in the design team, could no longer lead the way. Sales would go from from King to God-Emperor. This was new, and different and Gorkamorka was the result. When Rick went to confirm – not even pitch – the Christmas ’97 release, the empowered Sales team and the Executive panel said no. There was a new plan, and the Studio’s plans would be entirely suborned to the play for exponential growth. Gorkamorka was the result – the sound of engines and dakka echoing over sand dunes was the birth pangs of Kirby’s new Imperium.

Job’s a good un

In early 1997, the design team were working on their Christmas release, as they always were at that time of the year. The main game for Christmas was a fantasy follow up to Epic 40,000 – Warmaster. In ’96, just before the VISION was firmed up, Warmaster had been approved for release by the combined Execs. Production was well underway, with two armies in plastic, a fortress, and supporting siege machines all entering the six-up phase ready for tooling. This was a big project, another flagship release, and one that Rick was clearly very proud of, not only in the way he speaks about it, but that it was released, sadly bereft of plastic miniatures, three years later (and in a way went on to form the backbone of Rick’s later successes with Warlord Games). Warmaster was firmly killed off in a Sales meeting attended by the collective heads of the sales companies – UK and international. Whatever the state of the game going into the meeting, it never emerged.

What Sales wanted was something they knew they could sell everywhere, and after the relative failure of Epic 40,000 to shift in the required numbers to fulfil the VISION, it certainly wasn’t going to be Warmaster. Sales wouldn’t back another 6mm game. Whatever the Studio would create for release, it had to be 28mm. It most likely had to be 40k, too. In previous years, that might have been up for debate. Not anymore.

Tom Kirby was keen to give the sales companies anything they wanted

Rick Priestley

So, in the space of a meeting, the design team plan had changed. Not a 6mm fantasy game, but a 28mm game of….. something? What the hell was it going to be? Four months at least behind schedule, and nearing the cutoff point where plastics couldn’t be made in time, Rick was left with a “decision” – though perhaps less of a decision, and more of a forced response – to make, and quickly. For resources, the team had kits that were made but unreleased, the Ork Truck and half track, a very small amount of spare capacity, and the ability to fill a box with cardboard quicker than it could plastic. What they needed was a game – and sales had at least some of the solution.

Necromunda did so well, so the sales companies said We Want Necromunda 2!

Gav Thorpe

Necromunda 2 had been murmuring along in the background for a while. A skirmish 40k series investigating different parts of the increasingly detailed universe the team were building – Necromunda as both the inspiration and the first of the breed – was a popular theme in the design team. The ideas thrown out remain fantastic venues for exploration; a ruined craftworld, a Genestealer Cult planet (oh man imagine that one), a lost hulk. With the plastic kits in the pipeline, it quickly became obvious that something along those lines would fill that yawning void in the ’97 release schedule. “Orkworld” was on, using the Necromunda rules and whatever kits were available. While there’s no doubt Rick felt the time pressure, when it came down to it the responsibility for getting the game done fell squarely onto Andy. Memories after 25 years have differed as to the timeline of the game development, but it appears that instead of the one year leadup, Andy was faced with eight weeks. Eight weeks, and a design brief of “use the plastic kits we’ve got coming out”. Eight weeks.

I had to turn it around from a bag of notes into a full game, with a campaign, progression system, scenarios, the whole nine yards, because of the rush job and recycling, I just wasn’t professionally satisfied

Andy Chambers

Gorkamorka started, then, with the idea that the basic Necromunda system, a kind of extra-skirmished 2nd edition 40k would do for the basic bones of the game. Necromunda, in its 1990s incarnation, had been a popular release with wide takeup. It was still going fairly strong by 1997, two years after the original release. Necromunda had a fantastically long tail – the period post release when it was widely supported in stores, White Dwarf, and the Citadel Journal. It had come with rules for six gangs, the now widely known Escher, Orlocks, Delaque et al, and then bolstered by the Outlanders release – another four gangs – and a series of articles in White Dwarf. So far, so much like Necromunda would be, but with significantly more content. Necromunda would even have an additional gang published for the 1995 version of the game published well after the demise of Gorkamorka with the Pit Slaves expanded up and out of their hanger-on status in Outlanders into a fully fledged gang in White Dwarf 224 in August 1998.

When you compare it to Necromunda, you can see the time pressure at play in the design period for Gorkamorka. The game was never going to get multiple plastic kits (the Orlocks and Goliaths had both been in classic 2nd edition monopose plastic), or ten full gangs worth of metal releases. There was a single Ork sprue, so whatever you made in the core box had to be made out of that, so the game became about two identical gangs with slightly different progression rules. As the Truck and Track kits would be a major pillar of the release, the game needed vehicles, so vehicles joined the Necromunda bones to make the Gorkamorka we know and love. One more plastic kit – the Ork boys sprue being the only one commissioned for the game – was squeezed out in time. When models drive games, the mantra of GW since long before Gorkamorka came along, your game becomes about whatever models the company can make, especially when your game design time is significantly shorter than the lead time for plastic models.

On the other hand, metal models could be put into production quickly, and that’s where Brian Nelson came in, with the absolutely classic sculpts described above. But that’s all the game would get, with the longer lead time for Digganob allowing for another wave of metal releases. What the game needed was something that would let players explore the design space for themselves. The simple fix was in the vehicles, where a nice little rule – all models must be mounted, and all models must physically fit on the vehicle – threw open the conversion and customisation space that, in other games, would have been provided in the rules. While Andy, then and now, says that Gorkamorka was a rush job, this is a pretty inspired shortcut. We can’t provide the depth of model releases that Necromunda had, so instead, throw open the vaults and get hobbyists to do that bit themselves. The rush job led to the most enduring and fondly-remembered bit of Gorkamorka, the crazy conversions, sense of freedom and Orkish charm that seeped through every custom gang I saw on those tables in the Sheffield store.

Of everyone working on the project, perhaps (bar Gav) no-one loved this more than the Mail Order team. Gorkamorka was the high point of mail order customisation, and the “Mail Order Trolls” threw their weight behind it, pushing the game in their catalogues and semi-independent newsletter. Here was a game that was tailor made to boost their sales, back in the day when you could still very happily buy an individual component, have it picked out by a real life person, and mailed to you ready to superglue onto your buggy, trak, or bike. Gorkamorka, in the same style as other GW products at the time but to a far greater extent, exhorted you to dig into the back catalogue to pick up fantasy Orcs, 40k Orks, anything that might be found on a Space Hulk that had travelled through the warp for Gork (or Mork) knows how long. This was a game figuratively made for mail order, another bit of the rush job coming up trumps for what was then a fat sliver of the GW sales market. Unfortunately, and we’ll come back to this later, it wasn’t the sliver that the VISION was focusing on.

For something that was almost throwaway, as much effort went into it as any other design studio project

Gav Thorpe

Whatever happened to the design time the team – and the game – deserved, Gorkamorka wasn’t a half assed project. Massive time and effort went into the lore and modelling sections that stand head and shoulders above anything GW had put out since the 2nd Edition revolution in 40k lore. Gorkamorka established long-standing concepts in 40k like Ork spore reproduction, human explorator teams, even Necrons. Modelling and painting sections were comprehensive and clear, setting a standard that would be followed in every release to come. Combined with all those metals, the massive playtesting campaign squeezed into those eight weeks and the enthusiastic reception around the studio, Gorkamorka was a proper release, with enormous work put into it and a solid game coming out as a result. Somehow, a cannibalised ruleset themed around various plastic kits knocking about ended up on sale around the world in time for Christmas.

I’m proud of it now, if only for the durability of it, and that we pulled off a miracle, but at the time I really wasn’t

Andy Chambers

Da Hulk

That, more or less, is the story of Gorkamorka – or at least the one of dates, times, the how and when it all happened. However, there’s a deeper story to what was going on here. Gorkamorka was very much a product of its time and the tensions inherent in the increasingly fraught structure of GW, but even within that tension, the design team really had pulled off a minor miracle getting the game to market. Those competing contexts cast Gorkamorka into several very different lights. In the context of the new demands of the VISION, it was another release to fund growth. In the context of the design team, it was a barely copable burden slotted into a tough workload. For Sales, the teams who had demanded a change to the status quo – and got one – it was a bet. The success or failure of GW was a showdown. Could the Studio be forced to work to the sales plan? Would sales justify their newfound confidence with massive returns? If they pulled the bet off, then the primacy of sales over design was almost certainly cemented forever. If not, would the VISION – even could the VISION – really be the way forward? Either way, Gorkamorka, in all its glory and weirdness, was out in the world. In part 2, we’ll look in more depth at that bet by Sales, and what it all meant; for now, the Hulk was about to hit Angelis, and Games Workshop would never be the same again.