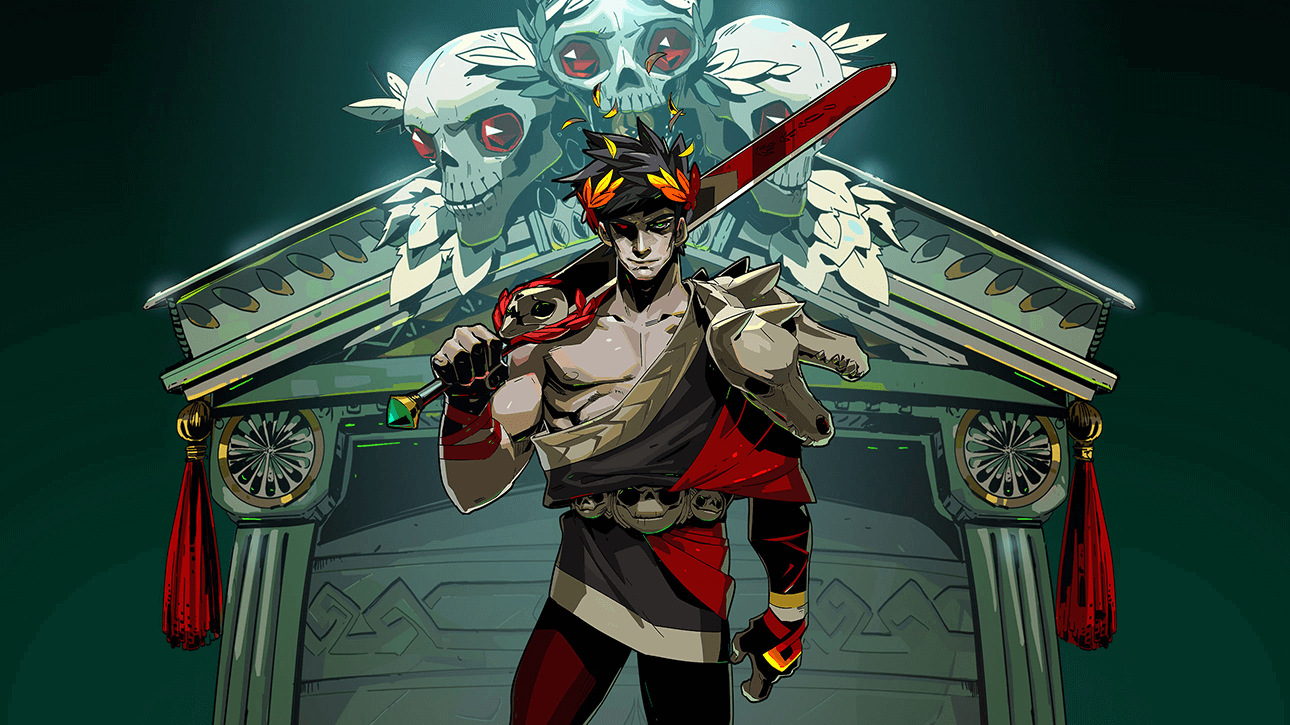

We’re starting something new here on Goonhammer; most obviously, it’s something that’s not going to have anything (directly) to do with Warhammer 40K at all. We’ve sort of run out of 40K video game titles to cover at the moment, and while more will definitely find their way down the pike and onto this website at some point, until then we’re going to be taking a look at the wider world of video games. Some of the time these will coincide with some aspect that might appeal to those interested in 40K — either the sci-fi aspect or its aesthetic — but we’re going to launch with a title that has no connection to the franchise at all, save perhaps a love of Greco-Roman pillar work: Hades, by Supergiant Games.

The premise is simple: you’re the Prince of Hell, and you want to get out of Hell, and you’re going to die over and over and over again until you finally do.

“Hades,” of course, is the name of the place in the Supergiant Games release by the same title; the Underworld also shares a name with your father. You play as Zagreus, who in real Greek mythology was an entirely incidental minor god who was likely an aspect of Dionysus, the god of wine; in this telling of the tale, he is the son of Hades himself, and he’s trying to get to the mortal world — which, in Greek mythology, is also the surface world — to find his mother. Hades doesn’t want to let him leave, for personal, petulant reasons as well as a hinted-at, larger plot, but Zagreus has the help of his estranged, extended family, the gods of Olympus, and thus the power to spite his father and escape… if he can survive the Underworld’s dire gauntlet. If not, no worries; he’ll sputter out of the pool of blood in his father’s audience chamber at the lowest level of Tartarus, and you’ll get to try again.

Hades is a rogue-lite, meaning it’s a run-based game where even failure to complete a run gives you more tools and resources to succeed the next time around. You’ll never carry over the powers of the Olympian Gods — things like Zeus’s boon to imbue your basic or special attack with lightning, or Poseidon’s boon of knockback tidal waves on strike, or Artemis’s boon of homing ranged attacks and higher critical rates, or Hermes’s boon of increased dash and movement speed, and so on — but there are a wide array of passive effects, tied both to Zagreus’s chosen weapon (as of this writing there are five in the game, all of which play completely differently, with a conspicuously empty spot for a sixth) and he himself, accessed via a point-buy magic mirror in his bedroom.

The gameplay is third-person isometric combat, within the same painted-animation genre as Supergiant’s previous titles, but occupying a distinct stylistic space (as each of those three games did from each other). There’s a mythological, larger-than-life aesthetic to all of the characters in Hades that wasn’t present in the squat, everyman Bastion, the fashonista sci-fi Transistor or the odd apocalyptic fantasy of Pyre. Like all Supergiant games, Hades is made for controller play; on the face buttons, players have a basic and special attack (the specifics of which vary wildly depending on what weapon is equipped), a cast which fires a lightly-homing projectile dealing a flat 50 damage with a limited number of charges (which can be regained by picking up missed shots from the environment, or hit shots when the enemy in question is damaged enough or defeated), and a dash, which functions as a directional dodge. Basic gameplay is very simple, but with each room you complete the Olympian gods, or the smith Daedalus, or the Underworld itself, might bless you with new powers that change the entire complexion of your build (the other option is you’ll earn those persistent resources that let you engage with the game’s passive between-run systems). In this respect, Hades splits the difference between a deck-building game like Slay the Spire and a traditional run-based combat game focusing on fast-twitch reflexes and technical competence. There’s always an element of luck to what kind of Zagreus you’ll have by the time you face dear old dad near the surface — but if you’re smart, just about any combination of godly powers can be worked into victory. And if not, there’s always next time.

Perhaps just as impressive as the game itself, though, is how Hades has handled development in Early Access. Most haven’t played the title thanks to it being Epic Games store exclusive for the first year or so of development, but I took the tumble and bought it at launch. I’ve kept up with it constantly since then, and I’ve been extremely impressed with the theory Supergiant has behind how to do this kind of ongoing development. At launch, Hades was a product with a complete gameplay loop: all of the mechanics were in there in one form or another, from the passive buffs to four of the five current weapons to the concept of NPC relationships to all of the forms of active, run-based power; some gods have been added since the game was first rolled out, but the majority of the roster was already there and usable. What wasn’t there was the majority of the content loop; you could only fight to the end of the first zone, and then if you succeeded you got bumped back to the start to do it again, while keeping all your accumulated power. There was even some special dialogue from Hades himself grumbling about “construction” in the Underworld that those playing the complete game (or even the game as it stands now, which more or less is just waiting on an ending zone) could never see.

The core gameplay loop, however, was in the title from the start, with all the mechanics that would eventually make it into the near-final product, and from there the progression was just building those mechanics out a little bit more. There haven’t been any forced resets of progress (and why would there be?) and even the first, earliest version of the game felt fully playable — in fact, I’ve still probably faced the original boss of Tartarus twice as much as any other boss in the game, and she’s now in a three-person rotation. Supergiant is hardly the first studio to recognize that this is the proper way to come to Early Access, but with length being the main constraint of the early product rather than diversity of play options, Hades encouraged backers to keep playing (and keep giving feedback) throughout the dev cycle, rather than playing it a couple times, then putting it down and waiting for the full release. Not every title has a concept that works as well for Early Access as Hades does, but given the precarious buy-in that Early Access games require — there’s no strict guarantee they’ll ever actually be finished, of course — it’s appreciated when something launches with a complete experience that promises to expand, rather than with an encouraging experience that promises to become whole.

Final Verdict:

It was worth it when it was $30 on the Epic Games Store, and now that it’s $25 on Steam with more than three times the content it had at launch, it’s something of a steal.