In a very fundamental way, FTL is a game about doors.

Let’s back up. FTL: Faster Than Light is not a new game; unlike with Hades or Slay the Spire, we’re not reviewing it here in an effort to help raise awareness for an early access title. We’ve got more of a historical interest. FTL was one of the games that pioneered the Kickstarter funding model — one of the first massive successes of that sort of backer build/early access type of development that now more or less runs the marketplace below AAA development. Released in 2012 and receiving a substantial free content update in 2014, it was also one of the first innovators in the rogue-like space that games like those mentioned above would build upon; Spelunky and Rogue Legacy were both part of that first generation. Spelunky is probably the most favorably remembered of that generation of games, but in terms of system innovation, FTL has it beat: instead of being a side-scrolling platformer that takes cues from the Castlevania and generic platformer lineages, FTL is in many ways an entry in the puzzle/optimization genre that Slay the Spire would eventually epitomize, though it’s far from a card game. Developer Subset Games would go on to make the follow-up title and in many ways spiritual successor Into the Breach, and it wouldn’t be shocking to see that game get review space here as well in the coming months.

The premise of FTL is rather simple, as the premise is for just about every rogue-like given that you’re intended to play them for hundreds of hours: you are the captain, or really the disembodied machine-spirit, of a single Federation starship fleeing the Rebel fleet to deliver information vital to the war effort against the Rebellion. You are being pursued by said massive fleet, moving left to right across various star sectors and trying to stay ahead of certain death — yes, it’s a bit weird that the “Rebels” are so powerful that their fleet strength is represented by an annihilation zone you must avoid at all cost, but whatever; the lore is not this game’s strength. To get from your starting point to the end of the game and the fight against the Rebel flagship (just roll with it), you have to master a couple of interlocking systems.

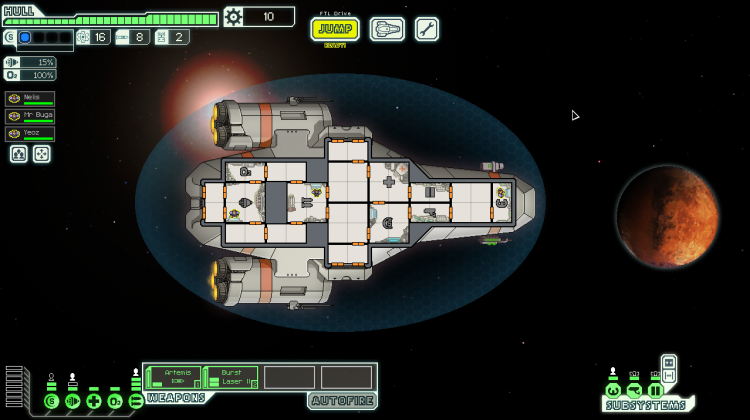

The first are your ship’s systems and subsystems: shields, engines, medbay, life support, and weapons from left to right on the left-hand side of the screen, then piloting, sensors, and doors on the right-hand side of the screen. Generally speaking, systems are higher-level concepts which allow your ship to do things in space and to other ships, and subsystems are secondary concepts that pertain to internal ship maintenance, though that’s hardly hard-and-fast; life support, piloting and medbay could fall under either. They are what they sound like for the most part; the only slightly unclear one is sensors, which allows you to see rooms in your ship that you don’t have crew members staffing. These systems define the strengths and weaknesses of your ship: a high weapons system ranking (defined by the green bars over the system) denotes a ship that can equip more powerful weapons to its hardpoints, while a high shield system gives more points of ablative shielding, and so on. You can upgrade these systems with scrap that you collect throughout the run, but there are a lot of things vying for that currency, so upgrades should be very carefully considered.

Interacting with these systems are your crewmembers, who can come in a variety of different races, each with its own benefits — there are rock men who are impervious to fire, slugs who cannot be mind-controlled, electricity creatures that can juice system output, and so on. Figuring out which stations each of your crewmembers are best suited to man and then keeping them alive is a key skill, and so is figuring out which crewmembers are best to take on as you proceed through events in the run. And you’ll probably lose one or two as things get hairy later on in your run.

Which brings us to combat. Unlike Slay the Spire, the vast majority of the game in FTL is actually happening in the individual instances of conflict. Combat works by, well, shooting weapons at each other, and trying to sequence their application well to deal with how your opponent has built their ship; if you’re using lasers and they’ve got a shield build, you’ll probably need to hit their shields more than once and then time your laser shot with the interval where their shields go down, and so on. If you know what you’re doing, and you’re very, very good at executing it (which you can be, due to a very generous pause feature that high-skill streamers like to eschew), you can save your bacon in most discrete instances of danger; it’ll be attrition that kills you. Bad rolls on shops and equipment can doom a run, but skilled play will save you more often than not.

So…doors.

There was a doors subsystem mentioned above; you can see that it has two toggles, which are respectively open all doors and close all doors. Individually, you can click on a door to open or close it, and force it to remain in that state, so long as the doors subsystem is functional. One thing the doors do seems very obvious, almost like their main function: when you’re boarded, they make it more difficult for your enemies to move from room to room. But this isn’t actually their main function. Take a look at the picture of that spaceship there, and notice that there are some doors that open into space.

This is the fury and the romance of the doors in FTL. Venting oxygen is one of the most important tactical decisions you can make, for a variety of reasons. The first is defensive in nature: venting oxygen starves fires that spring up when your ship gets shot with weapons, allowing you to suffocate those flames without dispatching crewmembers with fire extinguishers and taking them off their main work. The second is…still defensive, but more offensive: if you have the ability to lock boarding parties into specific rooms, and you open the airlocks out to space, you can vent the air and kill them (except for the races that can survive without breathing, of course, such as the robots). In certain games and certain builds, with robot-only crews, this can lead to situations where optimal play is to vent the ship to the void at all times, leaving the ship completely inhospitable to aerobic life and fire.

Later on in the game, both boarding parties and mind-control beams become staples of the enemy repertoire — if you want to get good at the game, you need to know how to control your doors. There are very few games you can say that about. FTL is almost certainly the best of them.

Final Verdict: FTL: Faster Than Light is $10 on Steam now. I’m running out of ways to say “this game would be worth that at $60,” so I’ll just say it outright, like that.