This is the second part of a two-part article series on the Royal Game of Ur sponsored by Spartan Development.

We’ve had a look at Spartan Games Ur: The Royal Game, and dived into the origins and history of the game itself. But the newest version isn’t just a repacked and reissued old classic, but a full rules (and board) update, so for our final article on Ur: The Royal Game it’s time to have a look at what’s changed and why. This isn’t a comprehensive article – you’ll have to get the rulebook for every little change! – but instead focuses on the three changes I found most interesting: movement, spawning and strategic points.

Why Update Ur?

First off though, let’s ask the big question – why update this most ancient of board games at all?

The interesting thing with all modern Ur rulesets is that they are already doing a huge amount of interpretation of the “original” game. Scribe Itti-Marduk didn’t write down a play-by-play guide in straightforward game designer language, but a form of gloss – as much a commentary and a set of asides as a guide to actually play. When we sit down and play Ur in older translated forms – like the Finkel ruleset that is probably the widest played – we aren’t playing Ur as Itti-Marduk played it. That game is largely lost to us, and where we do have information about it, it reads like this:

You will stand in exalted places; you will be powerful like a lion

You will go up the path; like one who weighs up silver you will draw fine beer

You will cross the ditch; like one who owns a herd, you will cut meat

From On The Rules to the Royal Board Game of Ur, Irving Finkel

As a result, all versions of Ur that are actually playable are interpretations – “house rules” for a game where the instruction manual was so well known that Itti-Marduk didn’t have to write about it. It’s much like trying to piece together how Warhammer 40k works from our Competitive Innovations articles. You’ll learn something, sure, but the rules of the game will be an approximation at best. Each iteration of Ur brings something new to the table: Finkel’s version is a chase game in the backgammon tradition. The Spartan Development version is almost more of a wargame, with fortifications, strategic movement and ambushes.

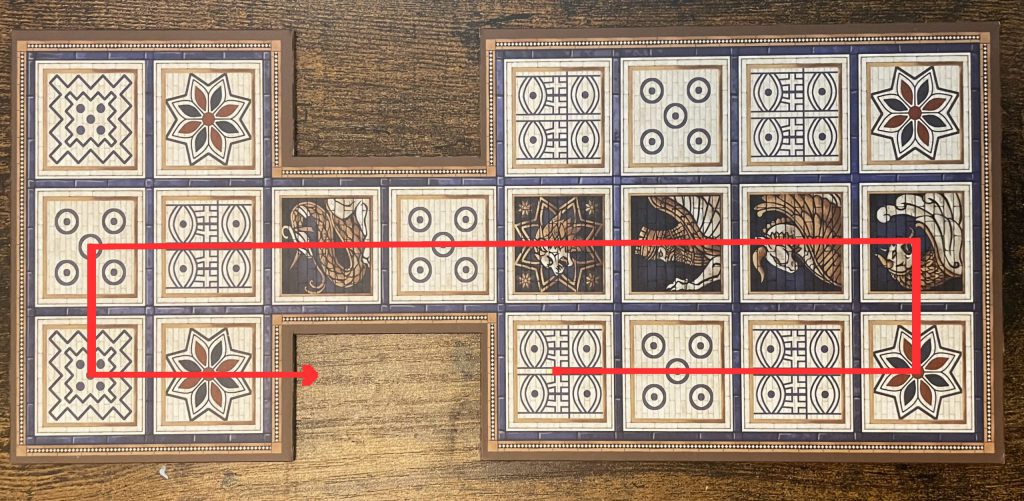

Movement

As we’ve previously discussed, the Game of Ur is a luck-based chase game where dice rolls (and a little strategy) discuss what you can do and when you can do it. In the Finkel Rules – the most commonly played version of the game – your pieces proceed around the board in an orderly fashion. Counters move along opposing tracks in a single direction, with a shared common path in the centre of the board. Your pieces can move over 14 squares – eight of which are “combat” squares where your opponent can take your pieces – with their final move being off the board. Each of your entrance and exit tracks are for the player alone, making safe areas where you can load up the board, reserve pieces in the hope of the particular rolls you need and generally make smug faces at your opponent when there’s nothing they can do to interrupt your stately procession to victory. These tracks are illustrated below:

Other suggested tracks are slightly more complicated, possibly navigating around the initial 3×2 area before moving down the central path and around the 3×4. I’ve played Ur like this and if I’m honest, it makes it a very long, slightly tedious game!

There’s a great deal of strategy there in determining when you move and how you do it, but the direction of travel is always forward. Ur: The Royal Game has changed this up, with backward and forward movement. That’s a relatively simple change, but it makes for a significant difference. Board states become more variable and more precarious, significantly expanding the possibility space for each move. I’ve illustrated this again below:

Shared entrance and exit tracks operate in much the same way, taking away the safety of your staging areas and replacing it with combat throughout. This very much opens the play space – all squares are potentially open to your pieces – and, again, makes for strategic, careful play. Except when you’ve specifically set it up, nowhere is safe and nowhere is off limits to you. This was a huge adjustment in my early games and opponents who weren’t conditioned to think of board sides as “mine” or “yours” really took advantage of my rules inertia.

There’s an interesting point here on the purpose of each game. If we accept – and lean into – the “original” Game of Ur having had a significant divinatory purpose, forward-only movement within your own line makes sense. Your pieces are drawn forward on a track individual to you, telling a story of the future. You can be interfered with, stopped, and have your pieces taken, but ultimately this is your future beckoning to you. Backwards movement gives you a choice to avoid it, but that isn’t the point – you can’t avoid your fate! Introducing backward movement actively strips away this aspect of the original and that aspect’s evolution into a “game” via the Finkel rules, but in doing so makes it a more considered and strategic experience. We aren’t relying on a board game to tell us the future (well, I’m not at least), but to test ourselves against an opponent, keeping an eye on every section of the board lest the dice roll against us and generally, you know, play!

Spawning

Part of that increased level of strategy is found in the new piece spawning mechanics in Ur: The Royal Game. Our “original” game of Ur spawns pieces on the entry tracks, one for each side. Spawning is risk-free and predetermined – if you roll high enough movement to move a piece onto the board, then there you go! You can place your piece on the entrance track, and that’s that; you rack them up and set them off on their journey down the board. Most rulesets have this as a safe and predictable practice. Each side of the board has a protected area, and each player can spawn pieces only on their own side. There’s definitely some strategy there, but the choices are largely premised around if you spend a roll on bringing a new piece onto the board – where you bring it on is limited to whatever tiles are empty out of your three or four (depending on dice roll interpretation).

Changing this up makes for substantially different gameplay. In Ur: The Royal Game, you can spawn pieces on either side track, not just your “own” and, depending on your dice rolls, in the centre of the board on certain tiles. You’re not only doubling the number of places you can bring a piece on, but you’re removing any safe squares from the board. You can no longer slowly build up a substantial army before they move down the board in absolute safety, because with a lucky roll your opponent could pop up right behind you, or spawn on top of an entry tile and remove your just-placed piece.

That’s a lot more decision-making to do, and a better game as a result. One of the downsides of the safer spawning of the older rulesets is that you (or your opponent) can start to stake out the beginning of the central path, eventually to a point where any move you can make will always leave a piece open to capture. Knowing that you can spawn pieces on both tracks allows you to develop more strategies around trading pieces, baiting out unwise moves, restricting opponent options with clever play and, in my experience, makes for a tenser, closer game.

Strategic Points

What brings all this together into a tighter, more interactive game is the addition of special strategic points to the board. The traditional Ur board has three types of tile – Entrance, Normal and Rosette. Rosette tiles, or “forts,” have a variety of different meanings and rules ascribed to them, usually along the lines of an additional dice roll or protecting a piece from capture. They’re important, and using them intelligently – often making sure you have a piece that could get onto a rosette to secure a reroll if the dice don’t go your way – is the key to victory, but they’re not essential.

With a new ruleset comes new interpretations of the tiles. In this version, the Rosette forts are the victory condition – hold all four Rosettes and you win the game. Positioning is therefore all-important, particularly if the classic rules are wedged in your head and you lose most of the review games through thinking you’re aiming to get pieces off the board (but who could possibly be daft enough to do that?). Holding forts in “Heaven” (the 3×2 section of the board) or “Earth” (the 3×4 section) grants you bonuses to your movement as well, so it isn’t quite all-or-nothing. Making an early play for one board section certainly makes your game easier, but it doesn’t guarantee you a victory for one important reason – pieces on forts can still be captured.

Enter our other strategic points, the tiles of Ishtar and Marduk. Ishtar, the Goddess of Love, War and Fertility (what a collection of things to be God of, eh?) owns the most powerful tile in the game, and one that presents a pressing strategic need. Hold Ishtar and your forts can’t be captured – but the Ishtar tile is still vulnerable. With only 7 pieces at your disposal, holding all four forts and Ishtar is tricky, but possible; you’ll need to outmanoever and outthink your opponent to keep it. Fitting for the Goddess of War! Marduk, patron God of Babylon itself, allows you – or your wily opponent – to set up ambushes and unexpected moves, acting as an entrance tile far up the board, bypassing a long and potentially dangerous slog up through the entrance tracks. Combining both tiles gives you a strategic point that you absolutely must seize and hold – Ishtar – and a way to do it when your opponent least expects it.

Ancient Mesopotamia was a land of important strong points, monuments that have lasted astonishingly well into the modern day, and, of course, the incredible Ziggurats. It’s good to see these echoed on the Ur: The Royal Game board – vital points to hold and monuments to your impeccable skill and intelligence as a player!

If your interest in this new version of an ancient game has been piqued by our coverage, do check out the Kickstarter for Ur: The Royal Game.

Questions, Comments, Suggestions? Contact@goonhammer.com or leave a comment below.