A few weeks ago, I talked about Apocalypse World and its impact on RPGs, particularly about the way AW is paradigmatically different from more “traditional” RPGs and how many of its “Powered by the Apocalypse” successors unfortunately missed the mark when it came to cohesive game design. Today I’d like to continue that conversation by highlighting one that did it right: Shawn Tomkin’s fantastic Ironsworn.

First released in 2018, Ironsworn is a sort of viking-themed medieval fantasy game that focuses on hard people living in a hard land. The central conceit of the game is that the PCs are of a class of people known as the “ironsworn,” those who swear solemn vows to see justice done, wrongs righted, fell beasts slain, and vengeance visited upon those who deserve it. In other words, adventurers embarked on dangerous journeys and quests that pit them against all sorts of foes, natural and supernatural.

The Setting

The Ironlands are a collection of regions with a broadly “fantasy Nordic” theme – jagged, heavily fjorded coasts, mist-veiled mountains, dimly-lit old-growth forests, rugged hills, expansive bogs, and to the far north the perpetually frozen wastes. But within this broad thematic framework, there are options and decisions for the players to make collectively – what was the calamity that befell the “Old World” and brought the people who now call themselves Ironlanders to this harsh realm? What is it that gives the Ironlands their name? How large or numerous are the human settlements of the Ironlands, and how are they ruled? For these questions and more, there are a set of prompts given that collectively set the overall tone of the setting. Here’s one of my favorite examples, which deals with “Horrors,” the fell supernatural entities that may or may not haunt the land:

- Nothing but stories to frighten children.

- We are wary of dark forests and deep waterways, for monsters lurk in those places. In the depths of the long-night, when all is wreathed in darkness, only fools venture beyond their homes.

- The dead do not rest in the Ironlands. At night we light torches, scatter salt, and post sentries at the gate. It is not enough. They are coming.

Each of the 11 questions in the “Your Truths” section has three such options to help “tune the knobs” on the setting, but the group is encouraged to “color outside the lines” if someone has a particular idea they want to run with. To provide further inspiration, each of these options has an associated “Quest Starter” that might be used to provide backstory or motivation to one or more of the PCs. For the second option above, it suggests:

“You bear the scars of an attack by a horror. What was it? Are those scars physical, emotional, or both? How do you seek to make yourself whole again?”

I found this to be a really engaging process, and everyone at our (virtual) table had some great ideas. This kind of collaborative world-building is nice in that it is somewhat limited in scope (much more so than Apocalypse World, which by design provides only the barest framework for the setting), but introduces new players to the idea that they even get to make these kinds of fundamental decisions about the setting in the first place. For a lot of gaming groups, you’re playing in whatever setting the GM happens to want to run and that’s that. But getting player buy-in during “session 0” of a game can really pay dividends down the road in generating long-term player engagement. Firming up peoples’ understanding about things like the power or prevalence of religion or magic especially can help manage expectations.

Character Creation

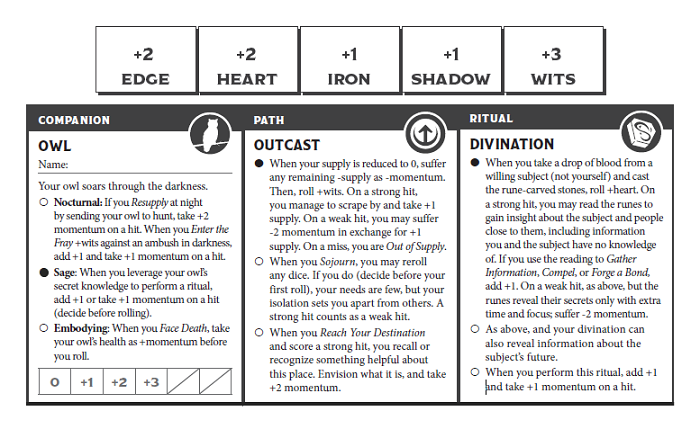

Like most PbtA games, character creation is slimmed down and fairly easy. Each character has five attributes – Edge, Heart, Iron, Wits, and Shadow – that collectively describe their personality and approach tackling problems. Characters with a high Edge are more apt to rely on skill or speed, characters with a high Heart are going to rely more on courage, willpower or empathy. Iron is all about forcefulness, aggression, and strength, Wits speaks to approaching problems with insight, observation, planning, and preparation. Finally, Shadow is about subtlety, cunning, and deceitfulness. As hacks go, I like these attributes and their split of the “parameter space.” The names of the attributes are both descriptive and colorful, they are distinct from one another, and they are well mapped to the fundamental actions the PCs are going to want to undertake. And importantly for a story-based game, they are marks of one’s personality rather than absolute, measurable physical quantities.

Among these five attributes, the player spreads out a +3, two +2’s, and two +1s, as like most PbtA games your attributes are actually a modifier to your rolls. One caveat with your attributes, though: choose wisely, as unlike most other PbtA games it is very difficult to increase your attributes through experience. Your character is much less mutable than in games using the usual “playbook” structure of Apocalypse World, which has both advantages and disadvantages. And when I say, “choose wisely,” I don’t mean that there’s an “optimal build” or anything ridiculous like that (lookin’ at you, D&D3.5), merely that your character will naturally approach challenges a certain way and you’ll want to be comfortable with that. Iron +3, Heart +1 means you’re more likely to want to solve problems with your fists than your words, which has… ramifications for how the story develops.

Assets

Once you’ve chosen your attributes, we get to one of my favorite parts of character creation in Ironsworn, which is the selection of your “Assets.” Broadly speaking, your Assets are the things that make your character special, and they break down into four categories: Companions, Paths, Combat Talents, and Rituals. Importantly, no two characters can have the same Assets, which preserves the PbtA concept of niche protection. Only one of the PCs can have a creepy-ass giant-spider as a Companion, for instance. Companions are animals – or even people – that tag along with you, and covers all the standard fantasy tropes like hawks and hounds and ravens and horses, but also includes some more exotic stuff like the aforementioned giant spider, the cave lion, the wooly mammoth, and the “young wyvern.”

Paths represent upbringing, skill, or professional training unique to your character, like being a Wildblood or an Outcast or an Herbalist or someone Banner-Sworn to the leader of a particular faction.

Combat talents are exactly what their name implies, but also serve to distinguish different styles of fighting during game-play – a Swordmaster is going to feel very different in a fight than a Shield-Bearer, which in turn will be different from a Cut-Throat.

Finally, Rituals give access to supernatural abilities, and this is one of the areas where the Assets really serve to help reinforce the game’s themes. These aren’t really “spells” so much as broadly defined abilities like Scrying or Divination. Most offer special moves complete with very evocative trigger conditions and effects, for example that for Bind:

When you wear an animal pelt and dance in moonlight, roll +wits. On a strong hit, you or an ally may wear the pelt and add +1 when making moves with the related stat (wolf-edge; bear-iron; deer-heart; fox-shadow; boar-wits). If the wearer rolls a 1 on their action die while making a move using the pelt, the magic is spent. On a weak hit, as above, but the wilds call as you dance; Endure Stress (2 stress).

There are something like 75 different Assets, each of which has a starting condition (selectable for Companions, fixed for the others) and two improvements, which you can unlock as your character advances. These generally improve your chances of success or the effect when used. At character creation, each player chooses three Assets for their character, and you can gain additional Assets (or improve existing assets) as you advance. In fact, improving or gaining new Assets is the only method of character advancement in the game by default (though there are variants described at the end of the rulebook that change this). Some Assets also have requirements (like Oathbreaker, which requires you to have forsaken a vow and is one of the few Assets that can – eventually – allow you to increase an attribute).

Finally, there are a few “meta-attributes” that define your character’s current physical and metal health (Health and Spirit respectively), overall preparedness (Supply), and degree of control over your current situation (Momentum). These will change throughout the course of a session as the result of the moves the characters make. One of these (Supply) is tracked collectively by the group if there are multiple PCs, which is great when your Alchemist wants to use the last of your resources to make a potion to help the Slayer overcome some fell beast but the Wildblood wants to hoard those resources for the journey to get to the fell beast in the first place (starving on your way to the beast’s lair is bad form, apparently, but what do I know).

The Dice

This is the biggest departure from your typical PbtA game, in that move resolution is not simply 2D6+attribute. Instead, the game uses 2d10 (the “Challenge Dice”) and 1D6+attribute (the “Action Die”). Degree-of-success on any given move is determined by comparing the Action Die to the Challenge Dice; if the modified Action Die is higher than both Challenge Dice, this is a “strong hit.” If the modified Action die is higher than only one of the Challenge Dice, the result is a “weak hit” (i.e. success with a cost or complication). And finally, if both Challenge Dice are greater than or equal to the modified Action Die, the result is a “miss” (a golden opportunity for the GM to complicate your life with prejudice).

This system also includes the concept of “doubles,” which is when both Challenge Dice show the same value. Doubles indicate a “significant” result – on a “strong hit” this could be interpreted as some kind of “critical success.” Likewise, on a miss this could be some suitably dire or disastrous outcome.

Momentum

Importantly, this is where a character’s Momentum comes in, as you can burn Momentum to cancel any Challenge Dice equal to or less than your current Momentum value. For instance, if your Challenge Dice are a 3 and a 9 but your modified Action Die was only a 2 (say rolling a 1 when using a +1 attribute), you’d be looking at a miss. But if your Momentum were a 3 or higher, you could cancel the 3, at which point you’d only have one Challenge Die exceeding your roll – which is a weak hit! If you wanted to go nuts and had 9 Momentum to burn, you could cancel both Challenge Dice and turn your 2 into a strong hit.

Momentum ebbs and flows during the session, and many of the choices in the moves are about accruing it or shedding it to keep worse stuff from happening. Managing your momentum is important and can mean the difference between a successful quest or getting the opportunity to become an Oathbreaker. Importantly, it’s another way the PCs can influence the odds in their favor; if you’re sitting on lots of Momentum, you can take bigger risks or take actions that use your less stellar attributes. It widens your horizons. But beware – Momentum can go negative and if you hit the minimum value of -6, you’re guaranteed to fail. Importantly, burning any amount of Momentum causes it to reset to its starting value (usually 2, though certain Assets or conditions can change this).

I’m always a little leery of changes to the base dice mechanics, but I’ve run the numbers on this one and the probability breakdown of miss/weak hit/strong hit roughly tracks with Apocalypse World’s dice mechanics. Specifically, it has a nice, broad, smoothly-varying “weak hit” range which is great, as it lets the PC succeed in what they are attempting but introduces additional complications that help drive the story forward – remember, in story-based games the rules aren’t modeling the physics, they’re modeling the story.

This dice mechanic took a little getting used to, but especially once we got the hang of using Momentum things started to work out nicely.

The Moves

This is where I think Tomkin really nailed the design – all of the basic moves in Ironsworn are thematic and tightly written, and collectively they cover pretty much the entire range of things the PCs are going to want to attempt as the story progresses. They are more numerous than the basic moves in Apocalypse World, but many of them occupy a space similar to AW’s “peripheral moves” for things like subterfuge or using barter. As such, I think they’re not too overwhelming in number and in line with what I want to keep in my head at any one time. A few of them bear special mention:

Face Danger

I have often gone on record as disliking Dungeon World’s defy danger move, mostly because it’s written in such a way that it conveys that a player can simply choose whatever stat they want when making the roll. This isn’t actually what is intended, but man is it confusing to people – especially those new to PbtA games in general. It is loosely-written enough that I’ve seen it provoke arguments at the table, as the Bard tries to justify rolling +charisma to avoid damage from a rampaging troll because it’s his highest stat and therefore the most likely to see him escape unscathed. Ironsworn has a similar move in face danger, but it explicitly ties the attribute that is being used to the approach the character is taking to address the situation. It clearly and consciously asks the player to state how their character is approaching the problem. It therefore puts the narrative first, and thus even though it uses the same basic structure as Dungeon World’s move it is just better-executed as a result.

Draw the Circle

This move’s trigger is pure magic: “When you challenge someone to a formal duel, or accept a challenge, roll +heart.” This move is 100% about reinforcing theme. It is instantly evocative of determined foes settling a disagreement with dedicated – but structured – violence inside an accompanying crowd of onlookers/witnesses. It explicitly puts forth the idea that duels are a thing in this setting, that using violence to solve disputes is both normalized and socially acceptable. From the perspective of driving home the game’s tone, this one is 100% gold and I love it.

Progress Moves

One of the other innovations of this ruleset is the inclusion of “progress moves.” Many of the game’s central activities – travel through the dangerous wilderness, fighting an enemy in open combat, or completing a perilous quest – are tracked with progress trackers, each of which has 10 boxes. Depending on the difficulty of the activity, some number of “ticks” or “boxes” are accrued towards completion of that activity each time a character succeeds. It takes 4 ticks to fill a box. Activities are rated as troublesome, dangerous, formidable, epic, or extreme, with troublesome challenges filling three complete boxes per success and extreme challenges filling only a single tick. The game then provides “progress moves” as a way to determine whether or not the PC has accomplished their goal (finished their trek, defeated their foe, etc) and what complications might arise as a result.

The mechanics of the progress moves are easy – simply roll two Challenge Dice and treat the number of completely filled boxes in the progress track as your Action Die. Importantly, Momentum may not be burned on a progress move.

As an example, the progress move end the fight governs, well, ending fights. If you were fighting a “formidable” foe, for each point of harm you inflict you would fill a single box in that foe’s progress track (and conversely, every time the foe did harm to you, it would be a base of 3-harm). At any point, you could choose to end the fight by rolling the Challenge Dice and comparing the total amount of damage you had inflicted so far to the roll. The more harm you’ve inflicted before choosing to make the move, the more likely to are to get a strong hit. A weak hit still makes you the victor, but forces you to select between a bunch of ugly choices:

- It’s worse than you thought: Endure Harm.

- You are overcome: Endure Stress.

- Your victory is short-lived: A new danger or foe appears, or an existing danger worsens.

- You suffer collateral damage: Something of value is lost or broken, or someone important must pay the cost.

- You’ll pay for it: An objective falls out of reach.

- Others won’t forget: You are marked for vengeance.

On a miss, well, the fight is over but you didn’t win it. You will pay the price (Ironsworn’s version of AW’s prepare for the worst, meaning the GM is about to put the screws to you).

In an abstract sense, this introduces a kind of sliding-scale “hit point” system to the game, where you are tracking progress towards an overall goal. While this can feel sort of weird for a story-based game – especially if you’re running in “guided” mode with a GM – it makes a hell of a lot more sense in the context of playing the game solo (more on this in a bit).

That said, if you are running the game with a GM, it is incumbent upon the GM to weave this progress into the narrative such that fights become more than the old “I stab it in the hit points until it has no more hit-points” that fights in D&D often devolve into. This is an area where I feel like the game’s mechanics put a lot of burden on the GM without necessarily giving the GM the advice they need to make this feel organic and natural rather than like the old “Progress Quest” game. I understand completely why these moves exist, but in play they feel a little artificial and jarring when compared with the rest of the game.

The other potential downside of the progress moves is that there’s nothing stopping you from getting enough ticks to fill two boxes on an “epic” quest and saying, “nuts to this, I’m finished” and rolling the dice. You’re unlikely to get a strong hit, but if you do then your quest is successful. You could be miles away from the object of your quest and never have even learned what terrible monster was guarding it, but now it’s yours and with no narrative support for how that happened. As a result, the “milestones” that make up a quest (i.e. the places you’re ticking progress when you reach in the narrative) feel somewhat disconnected from the actual story that is being told. In a fight or a voyage this is usually less an issue – you can often narrate landing a lucky hit or finding a shortcut – but for quests specifically it’s a bit of a disconnect. You’ll definitely want to anchor these in the fiction as much as possible.

Combat Moves

Ironsworn introduces a concept to combat that is missing from most other PbtA games, that of “initiative.” To players of traditional RPGs, the idea that many story-based games have no deterministic order in which the PCs or their foes take their actions probably seems like crazy-talk, but it’s a concept that is completely absent in Apocalypse World. Indeed, it is purely up to the GM to determine the order in which things happen, as well as how long each player’s action might take. It’s all bound up in giving the GM more control over the dramatic pace of the action in combat.

But Ironsworn brings the concept back – sort of. When involved in combat in Ironsworn, initiative isn’t so much the order in which players or the GM make their moves, but rather the term hews more to its original textual meaning of who is exerting the most control over the fight. A PC either has the initiative – and thus can dictate more about how the fight is progressing – or doesn’t, in which case they have to react to the NPC’s actions. Under the hood this is sort of what is going on in a well-run Apocalypse World game, but Tomkin pulls it out from beneath that hood and puts it in full view. Many of the combat moves (and options within those moves) are about seizing or losing the initiative, and in many ways it is as important as the amount of damage you inflict or sustain.

This does have a downside, however, as I feel like the difference between strike (the attacking move you make when you have the initiative) versus clash (the attacking move you make when you don’t) is not well defined in a narrative sense. The moves and their triggers are very clear and I have no quibble with the way they are written structurally, but I feel like differentiating these two moves in the game’s unfolding fictional space might be challenging, especially for new GMs.

Finally, because of way the “progress moves” work, I feel like combat in Ironsworn – especially against really tough foes – runs the risk of degenerating into “I do it again” with strike and clash. Here again I feel like anyone who is going to run Ironsworn would benefit from an in-depth dive into the MC chapter of Apocalypse World to hone their narrative skills to keep combat from becoming repetitive, and I wish that that advice were more up-front in Ironsworn itself.

Solo Role-Play

“What madness is this?!?” I hear you say. Well, believe it or not, Ironsworn is designed from the ground up to be able to support solo play. Create a character, put that character into difficult situations, and roll some dice to see what happens. “But where is the surprise?” you cry, “Where is the joy of discovery?” Well, Shawn Tomkin has you covered here too through the clever inclusion of “Oracles” to help the solo role-player decide what happens next.

The Oracles

The “moves” in well-written PbtA games have explicit success and failure conditions, and Ironsworn is no exception. For most of the basic moves, the failure condition is: pay the price. If you are playing with a GM in “guided” mode, this is the GM’s cue to do exactly the kinds of stuff they would do in any other PbtA game – fuck with you in a way that fits what is happening in the story. But if you don’t have a GM, coming up with appropriate consequences may not be so easy. After all, yours is the only character, so you have a vested interest to keep the consequences from getting too dire!

But if you’re playing solo, pay the price takes on a different meaning, because that too is a move in solo-play. This is what it says:

When you suffer the outcome of a move, choose one.

- Make the most obvious negative outcome happen.

- Envision two negative outcomes. Rate one as ‘likely’, and Ask the Oracle using the yes/no table. On a ‘yes’, make that outcome happen. Otherwise, make it the other.

- Roll on the following table. If you have difficulty interpreting the result to fit the current situation, roll again.

Roll Result

1-2 Roll again and apply that result but make it worse. If you roll this result yet again, think of something dreadful that changes the course of your quest (Ask the Oracle if unsure) and make it happen.

3-5 A person or community you trusted loses faith in you, or acts against you.

6-9 A person or community you care about is exposed to danger.

10-16 You are separated from something or someone.

17-23 Your action has an unintended effect.

24-32 Something of value is lost or destroyed.

33-41 The current situation worsens.

42-50 A new danger or foe is revealed.

51-59 It causes a delay or puts you at a disadvantage.

60-68 It is harmful.

69-76 It is stressful.

77-85 A surprising development complicates your quest.

86-90 It wastes resources.

91-94 It forces you to act against your best intentions.

95-98 A friend, companion, or ally is put in harm’s way (or you are, if alone).

99-00 Roll twice more on this table. Both results occur. If they are the same result, make it worse.

The rulebook also gives a couple of other easy options if you come up with a result that seems inappropriate, like reversing the dice on the d100 roll or looking at the results above or below the result you rolled. If something sparks your imagination or seems to fit, the pick that and run with it. By putting this kind of a randomly-generated system in place for determining consequences, it lets the solo player tackle those situations where they don’t have any inspiration for “what happens next” or where they really want to put some distance between their character decisions and the ultimate consequences of those decisions.

And as mentioned previously, this is where the “progress moves” become really important – If you are playing solo, it’s a way for you to disclaim narrative decision making and determine when a particular activity is “done” or an important objective is achieved. In this context, the progress moves make perfect sense and are actually really well constructed mechanically.

Collectively, the Oracles are a set of tables for things like NPC professions or personality characteristics, actions, themes, NPC combat actions, major plot twists and more. If you’re ever at a loss for how to incorporate the consequences of a roll into the fiction, chances are good that there’s an Oracle that can help give you ideas.

Finally, an aspect of solo role-play that is really interesting to me (and a number of other folks out there) is the utility of this kind of a system as inspiration for would-be authors. I have often heard writers say that “well-written characters can surprise even their authors” and this seems like a really good way to encourage that. A framework like this can force a would-be author to really put their characters into some dire situations or suffer really interesting consequences, which is a great exercise for anyone who wants to write believable characters. I guarantee that if you follow these guidelines and let the dice fall where they may, your characters aren’t always going to succeed at everything they try. This approach is a great way to save you from Mary Sue/Gary Stu syndrome. I write both recreationally and semi-professionally (for a small game company) and have recently been running a solo Ironsworn play-through as an exercise in incorporating unexpected elements into a narrative. So far, it’s been a lot of fun!

Oracles as GM Teaching Tool

In addition to offering solo opportunities for folks who may not have a regular in-person or on-line RPG group, I think that Ironsworn has another potential use as a tool to help GMs develop and strengthen the kinds of skills that will make them better at the job when they actually bring it to the tabletop. Running the game solo and using the randomization to provoke inspiration for consequences might give aspiring GMs practice at thinking outside the box, which in turn broadens one’s outlook as to what could happen next. It flexes your mental muscles for adaptability and improvisation, which will stand you in good stead when you need to do it in front of players. And if you practice envisioning what is happening narratively at each step, that’s good practice for giving the players an experience that is engaging and captivating.

Co-op Play

The same game mechanics that support solo play also support co-operative play, where you have multiple players but none of them is acting as the GM. When dice are rolled the whole table can get in on the action, deciding collaboratively what the results or consequences should be. My first exposure to Ironsworn was in this mode, and given that the COVID-related lockdowns had just started it seemed like a good way to ease into the (at that time) unfamiliar territory of gaming over Discord because no one had to take on the role of GM.

Unfortunately, this particular mode of game-play didn’t seem to work as well as we had hoped when put into actual practice. Much of this was due to the circumstances – without all being at the same table and all being relatively new to virtual gaming, there were no visual social cues and everyone was leery of talking over other folks. Similarly, people didn’t want to feel like they were making too many of the consequence decisions. When there were multiple suggestions, the process of hashing through them and deciding which to use took time and really broke up the narrative flow. One of my group dubbed it “GM-by-committee” and that felt like an apt assessment.

I suspect it would go more smoothly in person, but honestly I’m not sure I’d recommend it. If you are lucky enough to have an in-person or on-line gaming group and want to give Ironsworn a try, I think you’d have a better experience if one of the members acted as the GM, using the Oracles any time they were at a loss for what should happen next.

Hacking the Hack

One of my most frequent criticisms of PbtA games is that they often assume that the people playing the game are familiar with how PbtA games work. Many times there’s precious little advice on “how to run/play this game.” Not so with Ironsworn, which has a very good chapter called “Gameplay In Depth” that goes into a lot of the really important stuff about story-based games in detail. Concepts like centering the mechanics in the fiction, using the narrative to express difficulty, zooming in and out the scope of the moves, and structuring/managing quests are all explained really well, often with helpful examples. This is a real boon for players or GMs new to story-based games, and it’s very well-written.

Additionally, Ironsworn includes an entire section on ways to modify the game. Different experience systems, altering the setting, modifying or creating your own Assets, etc. I appreciate when authors take the time to give explicit advice like this, as they are in the best position to have a sense for what works and what doesn’t within the context of the game’s mechanics. I was really glad to see this section and look forward to seeing if anyone uses Ironsworn as a stepping-off point for another generation of cool games.

The “Delve” Expansion

Following shortly after the release of the initial game, the Delve expansion is like a set of Oracles for location encounters. It works by pairing a theme (Ancient, Haunted, Cursed, Infested, etc) with a location (Fortress, Tanglewood, Ruin, Ice Cave, and so on). Each theme and location has a set of features and a set of encounters, and when combined they can form a sort of “procedurally-generated dungeon.” This is mix-and-match approach is a godsend in terms of inspiration, especially for new GMs who aren’t used to running heavily location-based adventures in the context of a story-based game. Or who want to run “a dungeon” but don’t have a canned module to draw upon.

Even if you’re not interested in Ironsworn itself, it might be worth checking out the Delve expansion, because it is just chock full of neat ideas that you can steal for use in other games. As an example, the principles in this expansion recently inspired me to run this kind of landscape-centric encounter for players in my weekly Apocalypse World game, with three of the PCs exploring the ruins of a nuclear power plant in search of someone they felt they needed to kill. It worked out beautifully.

Aesthetics

One of the things I really appreciate about Ironsworn is it’s art. It’s all photo-based rather than drawn, which is a really neat choice. It brings a sense of realism to the setting. The panoramic landscapes and grizzled characters are all incredibly evocative, perhaps none more so than the dude fleeing through the snow from an Elder Wolf that graces the beginning of the chapter on “Foes and Encounters.” It definitely has an “Oh, shit!” vibe to it.

But in addition to reinforcing the setting and themes, I love the attention that has been paid to representation. Yes, there are plenty of hairy, viking-lookin’ dudes in there, but there are also women and people of color – all just as fierce and imposing and heroic as the hairy white dudes. We all want to see ourselves in the media we consume, and Tomkin’s choice of character artwork conveys the idea that even though the Ironlands might have a rough Scandanavian analog in our own world, fiction allows us to be whomever and whatever we want to be.

A Vow Fulfilled

Whether you are an old hand at PbtA games or new to the genre, Ironsworn has a lot to offer – especially if you don’t have a regular gaming group and want to try a solo-RPG. And I may just have saved the best part for last: it’s free. You can go to the official Ironsworn page and get digital copies of all of the goodies, including the Delve expansion and a host of handy player aids. Print copies are also available for sale, and the printed cards for the Assets and Delve locations/themes are really nice. You literally have nothing to lose, so go check it out. Then you too will be ready to swear an iron vow and take the first steps on your road to adventure.