It’s time for something a little different than our regularly scheduled content, a historicals project showcase. This week we’ve got HardyRoach showing off his 28mm Soviet women’s platoon and running down some of the history behind it.

As a historicals wargamer, it can get frustrating how rare it is to be able to depict anyone besides imperialist white dudes. That’s not to say that there’s not a rich tapestry to draw from, but that a combination of disinterest from manufacturers and perhaps limited roles for marginalised historical groups on the battlefield (particularly in the case of women) creates little incentive to create a great deal of miniatures outside the norm.

Thankfully, there are a handful of manufacturers that are dedicated to representing those who are too often forgotten by history. One of which is Bad Squiddo, an excellent company that focuses on depicting women in historical and fantasy settings. While perusing their site, I came across their excellent line of Soviet women. I, like many others, had heard about how the Red Army employed women as snipers, tank crew and engineers, but was curious about the feasibility of an entire platoon. This took me down a research rabbit hole, and also a significant spending rabbit hole, and now I have a full women’s rifle platoon. As will become clear below, the women’s rifle brigades were never deployed to frontline duty, and as such using them in a wargame will always be something of a “what-if?” scenario – but women undeniably did see frontline duty in other units, sometimes en-masse.

Before I show off the project itself, let’s go on a voyage of discovery on the role of women in the Red Army. Or you can skip to the bottom and just look at the models, if you’re some kind of rube.

Content Warning: the following contains passing references to sexual abuse, gender discrimination, torture, and sexual assault. At no point are these described in any detail.

Women At War

The full role of women during WW2 would fill many books, as indeed it does, but it’s worth having a quick overview for comparison’s sake.

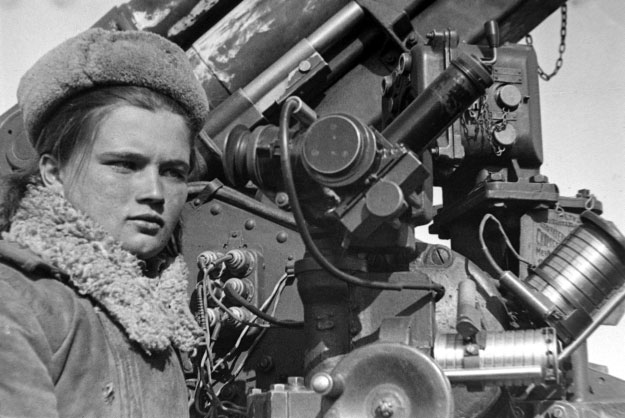

In the UK, there was general resistance towards women taking active frontline roles. Women were employed as anti-aircraft gun crew, but the rule was that they were not allowed to actually fire the weapon. Instead they acted as loaders, spotters and engineers. Other backline duties included roles in Women’s Auxiliary Airforce (which my gran was in, funnily enough), which mostly transported aircraft between sites in the UK; the Women’s Royal Naval Service, which fulfilled a wide role of non-combat duties, including radar operation and code-breaking; and the Auxiliary Territorial Service, which was the division that housed, among other things, anti-aircraft crew and spotters; and some women were even employed by the SOE and by european partisans as resistance fighters, spies and saboteurs. A total of 640,000 British women served in uniform over the course of WW2.

In the US women fulfilled similar roles as in the UK, but with a less pressing need for personnel, in much smaller numbers. Despite being considerably larger than the UK (don’t quote me on that), and with a massively larger armed force, the states fielded just under half as many women in uniformed duties as the UK (around 350,000). They were similarly reluctant to employ women in any kind of frontline duty. Nurses were the closest to the front at times, but were usually in stations well behind the lines.

Germany was the most unwilling, unsurprisingly, to field women in any kind of uniformed duty. It wasn’t until 1943 that Hitler authorised the use of women in anti-aircraft crew. Of course, as the noose closed, this unwillingness loosened considerably. By the end of the war, there were around half a million women auxiliaries in the Wehrmacht, including several thousand concentration camp guards.

There’s an obvious throughline across these countries – most governments were willing to deploy women in the military, but only for non-combat duties, and only behind the frontline. Germany is an exception, but this is a symptom of late-war desperation. As you might have guessed by now, the USSR was different, fielding women on the frontline in various duties as early as 1941. To discern why this was, first we need to examine the political conversation surrounding women in the USSR over the 1930s.

Women and Gender in Stalin’s Russia

The driving thrust of the 1930s in the USSR was modernisation. Still mostly an agrarian peasant nation with little industrial or financial clout, the 30s saw a breakneck advancement in industrial capacity, education and social organisation. This advancement necessitated the regendering of the workforce, an incorporation of women into a previously highly male-dominated sphere. This process was part of the development of the cult of the heroine – a reimagined Soviet woman acting as a representative of progress and modernisation.

Pravda and Komsomolskaya Pravda, the newspapers of the Communist Party and the Young Leninists (Komsomol) respectively, all but blanketed the Soviet public with comparisons between the lot of women in capitalist and fascist nations, and in the USSR – “fascist ideologues relegate women to domestic duties; ‘the place of women is at the hearth!’, they cry. What an evil taunt!”. Pravda argued that the Soviet women needed to be “mobile and prepared to substitute for men in industry and agriculture”. This process also included the expansion of womens’ presence in education, with literacy among women rising from 42% to around 83% between 1926 and 1939 (even if Soviet definitions of ‘literacy’ may have been somewhat more permissive than our own).

The language of political education in the USSR of the ‘30s was explicitly militant, as was the language surrounding the mobilisation of women in the industrial workforce. Soviet women were portrayed not as simple labourers, but as “fighters” for socialism, imbued with the values of optimism, self-sacrifice, heroism, and discipline. The Komsomol was a major organising force in this new Russia, viewed as the “most powerful, political mass non-party organisation”, providing a model of “steeled discipline” and military martyrdom for the Stalin generation of youths to emulate.

Media was inundated with depictions of socialist martyrdom, and films extolling the heroism of those who fought in the civil war were a frequent filmic motif. In the extremely popular 1934 film Chapaev, one of the main characters was Anka, a young woman machine gunner. In a triumphant moment, while the male soldiers are paralysed by panic, Anka grabs the Maxim gun and mows down White cavalry, turning the tide. Anka was the picture of the soviet “new woman” – serious, resolute, courageous, taking her place alongside her male compatriots in the new Soviet world. In 1935 the film Podrugy [Girlfriends] depicted three Red Army nurses during the civil war, on frontline duty. As in Chapaev they demonstrate courage under fire and demonstrate traditionally masculine military virtues, while still affirming the ‘feminine’ qualities that were popular under Stalin’s reign – attractiveness, loving, and desiring motherhood. In other media similar values were being extolled. The novel How the Steel was Tempered by Nikolai Ostrovsky became a massive success following its publication in Young Guard. Although the story depicted a male veteran of the civil war, the book became a major inspiration for the future frontovichki (the women frontline fighters). The political discourse of the time encouraged Soviet citizens towards a more gender neutral perception of heroism, and in doing so inadvertently imbued women with more of a militaristic spirit than what was perhaps intended (more on that below).

The Osoaviakhim is an important institution in regards to the eventual militarisation of women. Founded in 1927, the Osoaviakhim was a volunteer organisation funded by donations, charged with providing paramilitary training to civilians outside of school and working hours. Under the slogan “Every kolkhoz [collective farm] and every socialist factory a fortress”, the organisation established a network of military-sporting groups in every enterprise and educational institution. These networks taught and supported civilian communities dedicated to the pursuits of shooting, flying, parachuting, skydiving, gliding, machine gunning, and skiing, quickly becoming a favourite recreational activity for millions of youth. By early 1935 the Osoaviakhim claimed to have 13 million members, including 600,000 sharpshooters, 300,000 parachutists, 50,000 gliders, 500,000 aeronauts and 113 flying clubs. Pravda stressed the importance of “mass aerial sport”, and made a point of saying “not excluding young women”, and was frequently flush with images of uniformed, bemedalled young women sharpshooters, parachutists and pilots. By 1939 the organisation boasted nearly two million women members.

This fervour somewhat masks the often inadequate provisions of these sporting clubs. Frequently low on provisions, bullets and guns, and often with highly unsatisfactory standards of training. Accidents that resulted in deaths were not infrequent, as with those deaths came an increasing sense of unease about the presence of women in these endeavours. Women-only clubs and courses were dissolved in 1931 on the pretext of equality, while a maximum quota of 10% was set for women trainee pilots.

Numerous deaths in the mid to late 30s during flying feats created some unease among the powers that be. Although the Stalinist state was eager to valourise a handful of exemplary achievements by outstanding women, they were not intended to make the integration of women into paramilitary and military spheres a general rule. Increasingly, the priority was in imparting industrial skills to women that would allow them to free up male workers for the military. While Soviet media depicted women on the frontline, it was usually framed as a desperate necessity, rather than a model for a progressive, gender-neutral military. By International Communist Women’s Day 1941, it was clear that Stalin’s state had retreated from their previous lionisation of women as frontline fighters, which had inadvertently created an entire generation of young women who believed that they not only had a right to fight on the frontlines, but an obligation.

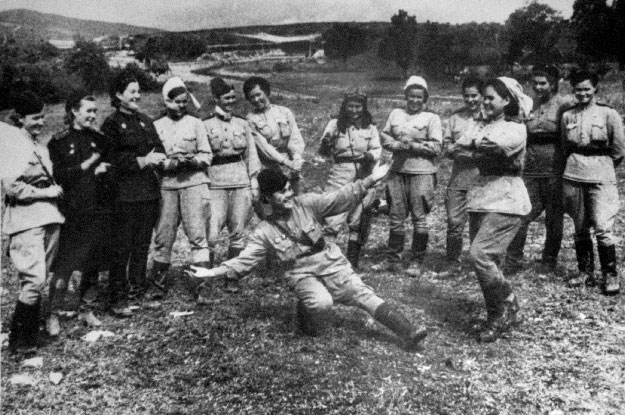

Early War Mobilisation

On Sunday the 22nd of June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Around four million soldiers drove deep into Russia territory, routing an unprepared and unprovisioned Red Army. Within 24 hours of the German invasion, thousands of Soviet women swarmed to meetings and recruiting posts, “begging, demanding and crying” to be sent to the front, weapons in hand. In cities, military commissariats were overwhelmed by young women, mostly aged 17-25, determined to enter combat, and the Komsomol, Stalin and the air force chiefs were inundated with letters from women Komsomol members. Though we lack firm data, it appears that in some areas women consisted of up to 50% of the applicants to join the army in the first months of the war, many of whom where accepted.

Women flooded into the traditionally male dominated workforce, and by 1943 represented 53% of industrial workers and 73% of the agricultural workforce. They were also immediately mobilised into civil defence: fighting fires, building fortifications, in the militia, and in anti-aircraft defence. Women made up 78% of Moscow’s 5500 self-defence units (samozaschchiti) formed over the course of the war (a total of 150,432), and 123,722 women volunteered for the 6000 fire-fighting units. Despite over a decade of military propaganda, popular participation in these units only came at the outbreak of war, once it became increasingly obvious that Moscow was ill-prepared for an attack. For nearly half a million women, the first taste of the war would be that of back-breaking labour, digging anti-tank ditches often under direct enemy fire. Girls as young as 15 were called up by the Komsomol to build defence lines, labouring 12-14 hours a day. After the Germans broke through at Vyazma, a further 250,000 workers (majority women) were mobilised for service digging up to 4.5km of defensive trenches and embankments per day. Over the course of the war, 600,000 workers (three-quarters women) constructed 676km of anti-tank trenches, 16,500 rifle pits, 27,000 firing points, 32,620km of anti-tank hedgehogs and 38,500 hectares of timber entanglements – all to protect Moscow.

Prior to the war, women were encouraged to join the medical profession as nurses and even doctors, with up to 40% of the medical profession being women by 1940. Despite this, by the time of the war the USSR medical sphere was woefully unprepared to deal with a major war, with inadequate medical services and a shortage of qualified surgeons. However women surgeons “proved to be hardier than the men, they could operate for 30-36 hours straight, and still be capable of working”. Likewise, female medical assistants could “work for 36 hours, but the men could only manage 16-18 hours”. Like in other armies, women took up a considerable role as nurses. Unlike in other armies, however, women nurses were expected to serve as frontline medics (despite initial reluctance). After 10,000 male frontline senior paramedics were killed in 1941, male paramedics began to be replaced by female ones, with only a month and a half of training. In the American, British and Canadian militaries, recruitment was drawn from registered nurses with professional experience – all were volunteers and unmarried, and already highly trained. By comparison, Soviet nurses were drawn from civilian populations, given short crash courses and shipped off.

The sheer brutality of the eastern front made a mockery of traditional military engagement rules, and as such women medics came under frequent fire, and in many accounts even took up weapons from the bodies of their fallen comrades and returned fire. In media and propaganda, Soviet nurses were presented as fighting, frontline heroes – defending their wounded charges with machine guns and grenades, rough and ready “militant girlfriends”. A far-cry from the Allied depictions of nurses, which were uniformly more traditionally “womanly”, with makeup and exceptional grooming.

Movements to deploy women as actual combat units were underway as early as 1941, with a secret decree requiring Komsomol women to undertake the same mandatory military training as men (Vsevobuch training). This decree was not made public until spring 1942, when young women were mobilised en-masse. By the end of the war around 220,000 women had received Vsevobuch training.

The Night Witches

One exception was made to the early war prohibition of women combatants – Stalin’s secret Order No. 0099, issued October 1941, allowed the formation of three women’s air regiments by 1 December 1941, spurred on by the Komsomol central committee and lobbying from Hero of the Soviet Union, Marina Raskova. One of these three regiments was the all-female night bomber regiment, the 588th/46th, which the Germans contemptuously dubbed the “night witches” (Nachthexen), a nickname the flyers embraced with pride. Out of the 86 women Heroes of the Soviet Union (HSUs), 30 of them came from these predominantly women’s units. Aside from hailing a few select heroines, such as Stalingrad fighter aces Yekaterina Budanova and Lidya Litvyak, the Stalinist regime seemed profoundly uncomfortable with publicising the exploits of the Night Witches. None of the main male war correspondents covered them, and it was not until 1944 that the writer Boris Laskin was allowed to visit the 46th Night Bomber Regiment. Indeed, the Soviets publicly denied that they were mobilising women soldiers.

Over the course of the war, the Night Witches flew more than 24,000 combat missions (including a record 324 sorties in one night), and won 25 out of the 30 HSU awards won collectively by these three air regiments. Some of the recruits came with previous experience as pilots or flying instructors, but there was overall a major shortage of qualified navigators, an unfortunate symptom of the pre-war propagandistic lionisation of the more glamorous role of pilot. While most of the women recruited were urban elites, from highly educated and politically active families, there were exceptions. Yevdokiya Bershanskaya, commander of the night bomber regiment, went from poor rural village to air force cockpit via pre-war aeronautical clubs. The allure of flight, particularly the role of combat pilot, was strong for the enthusiastic young recruits. Some women wept when consigned to a support or desk role.

Training was arduous, with three years of training crammed into four months. Most of the recruit pilots had flying experience, but few had experience with the demands of night flying. Even less experienced were the navigators, half of whom had no flying background whatsoever. Technicians and mechanics had to acquire theoretical and practical knowledge on the job, and the staff officers had no prior military training, bar a rudimentary three month crash course for flight staff.

Of the three regiments, the night bombers were the most poorly equipped. The 586th Fighter and 587th Day Bombers were equipped with the latest Yak fighters and Pe-2 bombers, at a time when there was a desperate shortage of planes. The night bombers, however, had to make do with the Po-2, a pre-war training biplane never intended for combat. The biplanes were without radios, armour, bomb bays or sights, and were only equipped with parachutes and machine guns near the end of the war. They only had four small bomb racks, and a top speed of 120km/hour. Despite their limitations and vulnerabilities for daytime use, they were effective enough at night, flying low (around 1200 metres, any lower and they risked blowing themselves up) and exhausting German troops with continuous harassment. They flew without instruments, only watches, compasses and eyesight, pilot and navigator communicating through a tube.

Bonds between pilots were incredibly intense, with a great deal of explicitly homoerotic relationships. Navigator Rudneva had a strong affection for her “best” pilot Nikulina, writing in her diary that “You are my delight, how I love to ruffle your luxurious locks, look into your little blue eyes…” Nikulina reciprocated affections in a night time song: “I will never cause you grief, Let it remain a secret forever more”. Not all were comfortable with these sorts of affections. Dokutovich, a pilot, wrote about another women, Zhenichka, who made pseudo-amorous advances on her. Scared of upsetting her, Dokutovich attempted to keep something of a distance.

In June 1943, the Night Witches were bestowed the title of “Guards” regiment, and granted a Guards’ banner, accepted with a reverential kiss by Commander Yevdokiya Bershanskaya. Despite their numerous accolades, most men in the air-force saw themselves as the real fighters, and dismissed the night bombers as “little girls”, and referred to them as the “death battalion”, a reference to the women’s battalions of 1917 that failed to prevent the seizure of the Winter Palace by the Bolsheviks. It wasn’t until the resurgence of Soviet historiography in the late 20th century that the Night Witches began to be remembered for their exceptional service.

Partisan Warfare

Part of the Soviet strategy for repelling the Nazis was in mobilising a civilian resistance to German occupation, a core element of the “patriotic war of liberation” which Stalin had called for in a 1941 speech. Secret directives to Communist Party and Komsomol organisations urged them to “ignite partisan warfare everywhere” in order to create “intolerable conditions” in the rear lines. The Soviet press publicised the worst atrocities of the Wehrmacht in grisly detail, looking to awaken “the flame of allpeople’s partisan war”. By the end of 1941 the partisan movement was 90,000 strong, with around 3% women, most of which were not armed fighters. Though a small number in comparison to other fields, the woman partisan was a central element of Soviet propaganda and in the creation of a cult of martyrdom.

In late November 1941, an 18-year-old partizanka called Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was captured in the village of Petrishchevo, around 80km west of Moscow. She was tortured and finally hanged. Zoya became the central point of a veritable cult, an almost canonised figure of martyrdom for the Motherland that was relevant even in post-Soviet Russia. As put by historian Yelena Senyavskaya, “only a symbol can fulfil definite ideological functions…converting the individual into a monument, a slogan, a legend, a model for mass emulation.” Zoya’s cruel fate was first publicised in Pravda in 1942. A fortnight later, she was posthumously awarded an HSU, and soon enough her mother was brought onto national radio. Zoya’s depiction in Soviet media typifies the general trend in the depiction of women in the Patriotic War – a synecdoche for the ravaged and terrorised Motherland, a victim designed to appeal to masculine, militaristic values to defend the innocent. Heroines existed to bolster the morale of male soldiers, rather than to encourage a generation of women to take up arms. Regardless, that was a consequence, at least to a limited extent.

In terms of actual partisan involvement, women were primarily employed as saboteurs, scouts and spies. The Komsomol CC and NKVD played a key role in the deployment of 648 women, working behind enemy lines. Maria Baturina was one such woman, a partisan who sent transmissions and summary reports to the Minsk underground via a hidden radio receiver. She later joined a partisan brigade as a scout – scouts would usually be plain clothed women, posing as refugees and residents. She later conspired with escaped POWs in the Jewish town of Slutsk to rob the police armoury and blow up the post office, radio and electricity stations. Disguised as a peasant, she delivered food and medical supplies to partisans hidden in the Pripyat marshes. Unfortunately, these endeavours were treated with suspicion by the authorities, seen as “damned Minsk spies” for the Germans. The liberation of Minsk in 1944 was followed by the mass arrest and execution of underground fighters. It wasn’t until after Stalin’s death that the group was able to clear its name of collaboration.

Mariya Osipova, a 29-year-old member of the Communist Party and Belarus supreme court, took the path from underground operative to political assassin. In spring 1943 Osipova resolved to eliminate the General Commissar for White Ruthenia (Belarus), Wilhelm Kube, a man responsible for the deaths of more than two million people. The Germans had threatened that if he were killed, “the population would be annihilated”. With the help of two other women resistance members, Nadezha Troyan and Yelena Mazanik, Osipova devised a plan to smuggle a mine into Kube’s lodging, which was placed under his mattress. At 2.20am on the morning of 22nd September, 1943, the mine went off, killing Kube. In retribution 2000 men, women and children were executed, and twice as many sent to concentration camps. Miraculously, Osipova, Mazanik and Troyan all survived to become HSUs.

Unsurprisingly, women faced not only the threat of torture and death at the hands of the fascist, but sexual discrimination, harassment and even abuse at the hands of their comrades. Relationships with men and pregnancy were a source of shame and ostracisation for women partisans, even in the cases where the pregnancy was the result of assault. Aleksandra Berezhnaya, secretary of the Dobrovensky district Komosomol, sought permission to have an abortion on the grounds that she had been raped by the Germans. The Komsomol had little sympathy, assuming that she was dissembling in order to cover up her failure to complete her mission behind enemy lines. She was dismissed from her post in disgrace. In some partisan units, militant young women with military experience were turned into cooks and laundresses by the commanders, who did not view them as fighters. Some women partisans were forced to “cohabit” with their brigade commanders under threat of expulsion, blackmail, intimidation, and even accusations of being German spies. Women in the isolated partisan units were at the mercy of their male commanders.

While there was a concerted Komsomol campaign to improve the lot and perception of women partizanski, they were to remain second class citizens in an overwhelmingly male movement, a state of affairs masked somewhat by the cult-like worship of Zoya and other women martyrs. While the authorities proclaimed high minded ideals of equality and sacrifice, the reality was rarely so rose tinted.

The Women’s Volunteer Rifle Brigade

By mid-1942, the Red Army was haemorrhaging male soldiers. In this desperate climate, the People’s Commissariat of Defence (NKO) proposed the formation of all-women’s infantry units. There are no official histories of the two most known units, the 1st Separate Women’s Reserve Rifle Regiment and the 1st Separate Women’s Volunteer Rifle Brigade, perhaps due to their incorporation into the NKVD’s “shadow army” at the end of 1943.

The motivation for the mass mobilisation of women in late 1942 was a direct consequence of the massive losses of personnel and supplies incurred by the battle for Stalingrad. In September 1942, the NKO demanded the implementation of previous orders requiring the substitution of women for young male soldiers in support roles in the rear and frontlines. In October 1942 and February 1943, Stalin authorised the formation of the 1st Separate Women’s Volunteer Rifle Brigade. The October decree stated that the brigade was established “to satisfy women’s desires to take up arms to defend their socialist motherland”. While this sounds like an incitement for women to join men on the frontlines, the actual main duties of the women’s brigades were to be as garrisons at military sites, railway junctions and supply facilities. A role that somewhat contradicted both official rhetoric and the aspirations of many of the young women who volunteered, expecting to fight on the front.

The women’s brigade (OZhDSB) had four rifle battalions, a training battalion, one automatic weapons unit, one reconnaissance unit, a communications company, a sapper company, an automotive company, a medical-nursing company, a mortar division, and a bakery. Initially the brigade was planned to have 6983 personnel, but the GKO increased the number of women soldiers responsible for crewing various weapons, in order to reduce weight per soldier (in a male unit, 7 soldiers crewed a 76mm gun, in the OZhDSB 10 women were required). Military training included endurance marches of 17-40km, night and day assault techniques, shooting, and specialised training in artillery, mine laying and anti-tank operations. In April 1943 the brigade commander, Lt. Colonel P.D. Karasaev pronounced the unit “ready for combat”. However, the unit was not deployed to combat, but assigned to non-military duties such as digging trenches, building defensive installations, and undertaking agricultural labour. Unsurprisingly, this was a disaster for unit morale. By the end of 1943 the brigade was incorporated into the internal security forces of the NKVD, and used for defensive duties, and later for law enforcement in liberated regions in 1944.

Recruitment of the brigade was a rushed affair, taking place between November and December 1942, which took its toll on the brigade from the off. Poor health, inadequate checks on social and political backgrounds, and doubts about the willingness of some to join the military abounded. Women being transported for training dealt with horrible conditions, and often arrived plagued by lice, flu, skin infections, malaria, and frostbite. Nearly 400 women were sent away for ill-health, and 54 were required to have a second pregnancy check, finding some pregnancies and venereal disease. Although nominally voluntary, the mass participation in the 1942-43 recruitment waves were not entirely spontaneous, being largely organised by the state through the Komsomol. Around 1000 women in the brigade had already been on the frontline prior to volunteering, but many others actively did not want to join the military. Private Anfisa Kravtsova declared that “we are doing nothing here, it was better in the rear and our parents fed us better”.

Living conditions at the Ochakova training camp were awful. The main barracks were repurposed from a rundown former brick factory, and were too small and spartan to adequately house the brigade. The rooms were dirty and dark, toilets didn’t work, there were no buckets, brooms or basins, and the women were forced to wash with snow. The only water came from a water pump, leading to frequent stomach complaints. The cooking and eating facilities in some units were filthy, and infested with rats and mice. It’s worth noting that these conditions were by no means remarkable. Both military and civilian accommodation in the 1930s was substandard, and these conditions remained extremely poor across male units as well as female.

Perhaps crueller than the horrific conditions was the deception that the women’s brigades would be deployed to the frontline. The new recruits were kept in the dark about the real purpose of the brigades, to fulfil rear duties, and thus had false expectations. During the first six months of its existence, the brigade was ridden with desertions. Ironically, these desertions were not to the home front, but to the frontline. Komsomol secretary Mikhailov noted that 131 women had run away by September 1943, most of which to the front, and more than 200 letters had been written to Stalin begging to be deployed to the front. Despite being clearly motivated by patriotic loyalty, these desertions were treated as a failure of military discipline, and as evidence of women’s weaknesses and unwillingness to adapt to military life. In reality, many of these women had the expectation that they would be trained as officers or middle-ranked commanders, and felt betrayed by the military. Some of them had already been on the frontline, so joining the brigade as rank-and-file privates with no hope of advancement, on rearline duty, was seen as a big step backwards. The spate of suicides, attempted suicides, desertion, drunkenness, and theft was seen as a failure of the individuals in question, rather than as an indictment of poor conditions and broken promises.

The initial plan for the OZhDSB was that the officers would mostly be men to begin with, with women commanders trained up to replace them as time went on. 913 male officers were temporarily brought in to command the 6240 women soldiers. In practice this idea conflicted with ingrained gender roles and prejudices. Male officers were often reluctant to acknowledge and respect the authority of their women superiors, and instances of sexual harrassment, cohabitation (forced and voluntary), and sometimes abuse created an untenable situation, and rather starkly reveals the difference between official proclamations of equality and the experiences of women in daily life. Only five women reached the highest level of leadership in the brigade, with several others appointed as politruki at lower levels. A training battalion was established with the aim to train lower-rank women officers in-house, with the Ryazan Infantry School responsible for training middle-rank women commanders. A series of gender and sexual disciplinary problems speeded up the proposed replacement of the all male junior commanders, and in the following months, discipline and order in the garrison improved.

Judging by the large number of disciplinary penalties dispensed on all sides, the relationship between the female politruki and the male commanders was not smooth. Often, male officers conducted themselves like a “boys’ club”, using their military experience, rank, and friends to avoid disciplinary action from theft of property, cohabitation, or mistreatment of women subordinates. In one case a machine-gun company commander, Lieutenant Morosov, lived with four successive women sergeants, and demoted or abused several others as punishment for refusing to cohabit. He was eventually expelled from the Communist Party and stripped of his commander for rudeness to the official inquiry and cohabitation.

By 1944, with the tide of war thoroughly turned, women were no longer needed for mass service, even on the rear lines, leading to the disbandment of the rifle brigade. Left behind was a legacy of betrayal and mistreatment. The women of the Rifle Brigade were promised a glorious fate, the chance to sacrifice themselves alongside their male comrades – what they received instead was horrific conditions, lies, and abuse.

Success on the Frontline: Snipers, Tank Crews and Engineers

While the Rifle Brigade was a failure, this only represented the mass mobilisation of women into infantry units. Elsewhere, women were trained and mobilised to serve on the frontline in various combat duties, including famously as snipers. Most notable among these women was, of course, Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a sniper with an official record of 309 kills who was elevated to the position of international celebrity. Despite her future fame, Pavlichenko was initially rejected when she volunteered for duty. Instead of joining up officially, she simply attached herself to a rifle battalion retreating from the Dniester River in Ukraine. Able to lie in wait for up to 18 hours, besieged by artillery fire, Pavlichenko saw herself as a warrior, and freely admitted “I can observe German corpses indifferently, but a living German I cannot stomach”.

Pavlichenko, like Zoya, became a symbol of Soviet womanhood at war. Unlike the partisan martyr, she was not a victim of fascist brutality but a militaristic inspiration, not just at home but abroad. With Stalingrad under threat in 1942, the USSR was eager for the Allies to open a second front in Western Europe. 26-year-old Pavlichenko, along with male sniper Vladimir Pchelintsev, was sent on a tour of the US, Canada and Britain, during which Woody Guthrie wrote a folk song about her – “‘cause more than three hundred nazzy hound/ Fell by your gun”. In the US, she became frequently frustrated by the insistence of US women journalists to ask her about underwear, makeup and the cut of her uniform: “one reporter even criticised the cut of my uniform, saying that in America women wear shorter skirts and besides my uniform made me look fat. This made me angry. I wear my uniform with honour”.

However skilled Pavlichenko was, she was only one woman. And yet she partially inspired the women’s “sniper movement”, beginning with the training of snipers on the front, and ultimately formalised with the establishment of a central training school in the spring of 1942, which accepted both men and women. In May 1943 The Central Women’s School for Sniper Training was established, which went on to contribute the bulk of the 1885 women snipers deployed on various fronts, and the school commander boasted that in a mere 16 months “the school had accounted for 18-20,000 dead Fritzes”.

Conditions during training were rough – plank beds, poor rations, and continual physical exertion. Training consisted of battlefield preparation: digging trenches, preparing firing and defensive positions, camouflaging, crawling and target practice. “For an entire day you had to run, crawl and shoot, however much you wanted to collapse and sleep. Your legs pained, your eyes ached from the prolonged stress, and your shoulder throbbed from the recoil of the rifle butt.” In addition to the physical training, the sniper students were required to attend regular political classes, aimed at instilling them with “pride in their moral superiority over the enemy”.

Like in the Rifle Brigade, gender relations were often strained and occasionally abusive. Junior Lieutenant Mazhnov “love to show his authority” over the female recruits, covertly force-marching them against the orders of his superiors, and forcing one of his subordinates to crawl through a filthy puddle in freezing weather. He was later dismissed for his abusive conduct, and replaced by a woman, Junior Lieutenant I. Papikhina, who led the platoon to the front. Soon enough women commanders replaced men in all platoons. “Things became somewhat simpler”, recalled a recruit, “not that this meant there were fewer demands on us…no, it was simply that we were better understood.”

These snipers were deployed as a full unit (rather than being distributed across multiple units) to the front towards the end of 1944, though the reception by their male comrades was somewhat mixed, to say the least. The Reserve Regiment of the 31st Army “offended” them, with the commander asking “Well, why have you come, to fight or…fuck?”. The reaction from the 611th Rifle Brigade to which they were later assigned was more polite, but somewhat sceptical – “they’ve sent us young girls”. Despite that, they participated in the Russian offensives into Germany, right up until the end of the war.

While not mobilised on a mass scale as they were with snipers, women had a role in various other frontline duties. A few dozen tank crew, and even a few tank commanders, were women – Nina Ilynichna Bondar, who commanded a T-34, and Alexandra Leontievna Boyko, who commanded an IS-2. Reports of the occasional riflewoman in men’s units, and even of entire women’s platoons within male companies, have surfaced in the years since the war. Women engineers were fairly widespread in both frontline and rearline duty, serving as either mechanics or sappers.

The sad addendum to this story is the fate which befell POWs, male or female. Despite experiencing unimaginable horror in concentration and POW camps, upon liberation many women found that their troubles did not end there. Those who had “given themselves into captivity” were suspected as traitors, cowards or even collaborators. Authorities also fear that the frontoviki, having seen the more developed central European countries, would become “neo-Decembrists”, infecting the Soviet polity with foreign reformism. Anna Timofeeva-Yegoreva was one of the few women fly the Il-2 shturmovik ground-attack aircraft, and was also one of the few women aviators to be captured. Shot down on her 277th mission over Poland in 1944, she was imprisoned in a concentration camp for five months until being released by a Russian tank unit in January 1945. Despite this, she was subject to harsh suspicions, and was only awarded her HSU in 1965. In actuality, she had been awarded the HSU in 1944, under the assumption that she had died. When it was found that she survived as a POW, the award was stripped from her.

Despite mobilising women on a larger scale than any other nation during WW2, they quickly became forgotten by an uncaring post-war state, eager to valorise the Great Patriotic War through the lens of male struggle – and even then, only through heavily propagandised accounts. It was only in the Khrushchev era that memoirs of the war by the people who actually fought in started to see the light of day, mostly in floods of accounts from male veterans, but occasionally from women as well. Despite the heroic individual examples of great women fighters on the frontline, such a thing was the exception, not the rule, even in the most desperate days of 1942-43.

The Project

Phew, that was quite the trek. If you’re still there, well done for being a history nerd.

The models themselves for this project are almost all from Bad Squiddo (bar the vehicles and bannerwoman), who I recommend heartily. I was aiming for a depiction from around the autumn of 1943 or 44, and as such I purchased a mix of summer and winter uniformed troops, with the idea that not all troops were either able or willing to switch to greatcoats just yet.

My platoon scale game of choice for this period is Chain of Command, so I constructed the force itself with that in mind. A late-war Soviet Infantry Platoon in that system has a baseline of three squads, each consisting of 7 riflemen, two LMG crew, and an NCO; as well as a commander.

For support options, I limited myself to things I knew that the OZhDSB had access to, or were more likely to have access to had they deployed to frontline duty. An anti-tank gun, tank hunter squad, anti-tank rifle team, HMG squad, sniper team, mortar team, sapper team, and scout squad were all easy first picks – the OZhDSB demonstrably had access to all of those resources. When it comes to armour, however, things get a bit more difficult. The brigade had an automotive company, but that would have been trucks and cars, not tanks. I could easily have gone without tanks in Chain of Command, but damn it, tanks are cool. A T-34/76 seemed like a reasonable allowance, there were recorded women T-34 tank commanders. A BA-10 was more of a stretch, but justifiable due to its age, the unit was unlikely to receive much other than obsolete dregs. Finally an SU-122, because they’re cool. Sorry, the rule of cool applies. All three vehicles are from Rubicon.

I encountered something of an issue with the anti-tank gun – Bad Squiddo do not yet make a gun crew, just mortar and HMG crews. I took a couple of riflewomen, snipped off the ends of their rifles, then filed the remaining bits smooth so they appeared to be large shells. The remaining two crew are an artillery spotter, with radio, and a tank rider, conveniently pointing towards the enemy. I also made a square base to represent tank riders, but this is mostly if I use this platoon for Bolt Action, or some other game that allows for tank riders (Chain of Command does not, as tanks were ridden between battlefields, not on them).

For painting, I first zenithal primed everything with an airbrush, then gave all the uniforms an airbrush coat of Vallejo Khaki, and the helmets a deep green. The fun thing about Soviet uniforms is that you can get away with basically any shade on the spectrum of green to brown. Uniforms were made somewhat hurriedly, and there wasn’t any real system of standardisation. Besides after field use uniforms tend to change colour from wear, so yeah, any shade you like, as long as it’s earthy. Greatcoats in particular varied enormously in colour, so they’ve been painted a mix of khaki, green and dark grey-green. The scout squad, I figure, were better equipped for the winter due to their more precarious position, so they’re equipped with the white smocks and trousers issued to snipers and scout units for winter camouflage. The snipers have khaki uniforms, but with winter capes for the purposes of camouflage.

Equipment pouches and boots were likewise extremely non-standardised colour-wise, so I opted for a deep green for the pouches and a dark brown for the boots. The guns get a light brown on their wooden housing, with some lowlights of deeper brown, and the metal on the guns get a coat of Vallejo Metal Colour Gunmetal Grey, then a Nuln Oil wash, then some Gunmetal Grey highlights.

For skin tones, most troops have a somewhat pale beige, but Russia was more ethnically diverse than is often credited, so I threw in a few troops of darker skin tones. Most troops have been painted with black or brown hair, but a few are blonde or ginger.

The vehicles got an airbrush layer of olive green, followed by judicious weathering and coats of Green Stuff World’s White Dust liquid pigment, to reflect a hasty white-wash. Tank crew uniforms tended towards dark grey or green, but again, any colour in the green-brown spectrum works as well.

For basing, I wanted to give the impression of the beginnings of snowfall. First everyone gets a layer of polyfill to cover up their puddle bases (I would have used the new Wargames Atlantic bases with the double-sided feature, but alas, I didn’t have them yet). Then a layer of Vallejo Russian Mud, which is a very dark brown with little chunks of foliage, followed by a drybrush of a deep brown. On top of that went Geek Gaming Scenic’s autumn flock, followed lastly by a dusting of their snow powder in small patches.

Thanks for joining me on this adventure, and stay tuned for perhaps some other showcases and histories of underrepresented troops.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.