The Warhammer 40,000 universe is a massive place, and the “Narrative Forge” hobby articles encourage thinking outside the box (literally) when putting models together and stretching yourself out in the hobby. They aim to make hobbyists and players comfortable growing beyond imitating the models they see in their Codexes and playing the rulebook missions, and serve as a source of inspiration for anyone wanting to forge new experiences in the hobby. This week, Robert “TheChirurgeon” Jones is picking his multi-part series on campaigns back up, this time talking about running map campaigns for Warhammer 40k, Age of Sigmar, and a Kill Team (or any other systems, really).

Alright, break’s over. I’ve skirted around doing this article long enough, but now it’s time to talk about Map-Based Campaigns. For most wargames, map-based campaigns are the first thing everyone thinks of, with armies pushing around a larger battlefield or realm, fighting over key points of interest as players make tactical decisions about when and where to strike.

Map Campaigns

Map campaigns are so named because they feature a large map for players to compete over, allowing players to plan moves, occupy territory, and play out some of the oft-neglected aspects of warfare in the Warhammer universes, accounting for things like supply lines, fortifications, and attrition as players attempt to conquer the city/country/realm/planet/system/galaxy. Map campaigns add an entirely new layer to the proceedings, essentially creating another full game outside of the standard game that players must consider. They’re also some of the most open-ended, allowing players to determine when and how they challenge other players, and often, the battlefields they’ll be clashing over.

That said, Map Campaigns are also the most challenging and time-consuming campaigns to run. Because they’re essentially a new game layered on top of games of Warhammer, they require you to design or implement well, an entirely new game for players to play. That means you’ll need to design or pull mechanics from somewhere, and give your campaign rules the same considerations a designer would give any game. Also, note that, while all of your players are (presumably) into Warhammer, they may not like this other, non-Warhammer game very much and not share your interest in it. And because of the complexity involved, map campaigns need players who are A. Experienced veterans with the systems you’re playing with, and B. Very into the campaign idea and committed to playing games.

Why Run a Map Campaign?

There are a few reasons to run a map campaign:

- They’re cool as hell. Everyone dreams about running map campaigns, which from a distance, are easily the coolest-looking campaigns, with large maps showing army movements and control. They also give you the biggest feel of being a real general, commanding troops not just in an individual battle, but over the course of an entire campaign – you aren’t just moving from game to game in a preset fashion, you’re determining where and when your troops will strike.

- Tons of player control. Map campaigns give players the most control over the narrative, and make it easy to see who is in the lead and who’s behind at any given point. They also make the campaign feel more “real” as an object than other campaigns, which may

- You have experienced, dedicated players looking to take the next step. More than any other campaign type, map campaigns demand that you have players who are really “into it.” If your players have been talking excitedly about playing in a map campaign, that’s a good sign.

- Clear game outcomes. Map campaigns have some of the clearest outcome tracking of any campaign type – you win, you increase your map control. Lose and you cede ground. This makes it easy to visualize who’s in the lead at any given point.

- Works well with teams. Map campaigns can handle teams pretty well, and can support things like alliances and intrigue, where players can cede territory willingly, allow save passage, bargain for resources, or potentially team up to take down a bigger foe.

Consider a Map Campaign if: You have 4 to 8 people who are really into the idea of a map campaign, you’ve got a ton of time and energy to devote to campaign prep and materials, and you’re looking for an excuse to stretch your game design wings and fly.

Before You Start: What’s Out There

Before we dive into building your own map campaign, it’s important that we explore what’s already out there; we don’t want to reinvent the wheel but rather start with something that has been tested and worked before, then tweak or alter that as we see fit. You may even find that one of these systems perfectly encapsulates what you wanted to do anyways, and you don’t need to do the extra work.

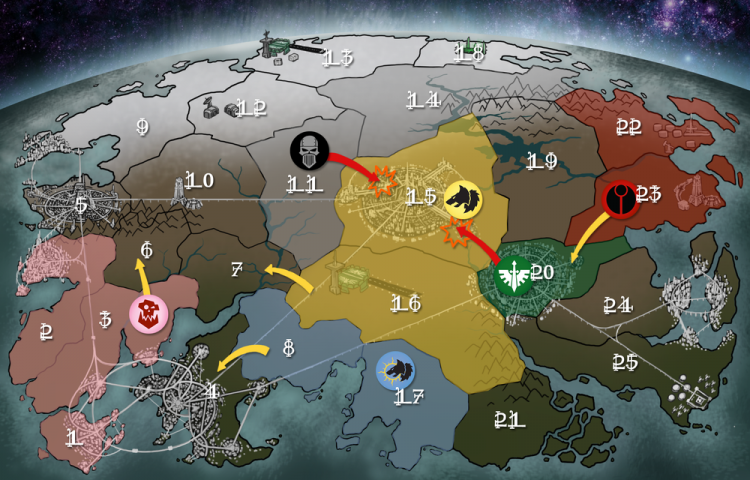

Firestorm Campaigns (Age of Sigmar)

Published in late 2017, the now out-of-print Firestorm campaign supplement for Age of Sigmar laid out a map-based campaign for the Age of Sigmar, set up for four players (though it could handle more with some custom work on players’ end) to clash under the banners of the Great Alliances over a map of territories in the realm. It’s set up to ideally be played by a small group of friends who can meet up on a weekly basis to review the map, make strategic decisions, and challenge each other over territories.

How it Works

Players start off in four corners of a large campaign map representing the available territories. Players then blind-place altars on the map to represent points of power for their factions. Each round, players challenge other players to battles over territory, either neutral or controlled by a player, and determine the size of the game they’ll play. Then each player draws a hand of 6 Domain cards to apply to the game (cards are discarded at the end of each round so there’s no incentive not to play all of them). For the most part, the cards give players effects in the battle, though most are either awarding Strategy Points, which are used to buy a series of in-game effects, or Muster Points, which are used to bring larger armies to the game – when building an army for a battle, each muster point is worth 10 additional matched play points in your army. Battles fought on a player’s home turf or territories they control with a garrison may give further bonuses (such as extra Domain Cards), so challenging a territory a player controls will likely result in a tough uphill battle against a larger army. The territories themselves also affect the game, with random effects that change the battlefield, give players specific effects, or provide extra bonuses to the winning player.

After each battle, the winning player puts their command marker on that map territory to signal that they control it and then players are awarded Build Points and Glory Points. Build Points are used to build garrisons on controlled territory or buy more Domain cards to add to their deck (these have better effects and tend to represent build-able structures like walled settlements). Glory Points are essentially campaign victory points, and the campaign has two ways to win: Either have the most glory points at the end of the campaign, or conquer each of a set of three special map territories and reforging the Sceptre of Flame, the magical mcguffin everyone is fighting over.

In addition to this, the Firestorm campaign gives special rules to each of 10 different Allegiances, so you can represent that you’re fighting for Archaon or Nagash or whoever in this specific campaign.

What It Does Well

Despite being a bit rough around the edges, there are a few things that Firestorm does pretty well that are worth considering if you’re building your own map campaign and looking for inspiration:

- Challenges. The challenges mechanic neatly solves the issue of how you’re going to handle unclaimed regions: A player can’t claim a region without fighting someone for it. The aspect of allowing players to call each other out, then determine where they are fighting can help solve this nicely.

- Home Turf bonuses. Having a bonus for trying to conquer a held/garrisoned territory makes it tougher for players to just take territory from other players, which is something you will generally want to happen more later in the campaign as opposed to earlier. Map campaigns are all “zero sum” affairs at the end, but early on there should be opportunities for players to build up resources without losing anything if they lose, to prevent snowball effects.

- Alternate Win Condition. The alternate win condition of conquering three specific territories and reforging the Sceptre adds some much-needed tension to the campaign, and can give players who are behind a way to eke out a win despite ceding massive amounts of territory. It also gives players a way to meaningfully band together to defeat an advantaged player late, by making an alliance in a last-ditch effort to stop the player in the lead.

- Card Assets. The campaign card assets are more than just cool resource for your players to lose between games – they give players a tangible resource that can be spent or traded to other players (the campaign has mechanics for this), allowing for negotiations and intrigue that can really enhance the feel of the campaign and lead to some cool stories.

- Build Points. The ability to use build points to either garrison regions or buy cards to add to your deck creates an interesting feeling of being able to build upon and improve your captured territory, while also adding a bit of an interesting deckbuilding game aspect to proceedings that will be familiar to anyone who has played Dominion or similar games.

- Allegiance Rules. The Allegiance rules are neat, and create some interesting incentives to build armies that are thematically appropriate to the setting. That’s a neat idea, even if it does potentially create a bunch of extra balance headaches – it can be a good way to encourage a certain type of army construction.

What It Doesn’t Do Well

Firestorm is clearly an early work for Age of Sigmar; it hews closer to the game’s pre-General’s Handbook sensibilities and tends to gloss over a lot of necessary mechanics in its rules. So there are some aspects of it that are pretty clunky:

- Fixed map. This isn’t a huge issue, but if you want to play more than one Firestorm campaign, it’s the same map every time.

- No priority rules. The Firestorm campaign has players challenge each other each round, but doesn’t offer any helpful rules or structure around who can issue challenges to whom, and who has priority when declaring challenges. The rules specify that players should take on challenges as “honour” dictates, but can’t issue or accept other challenges while they have an open challenge. This means that the first player to yell out their challenge has an advantage, and a winning player could just keep challenge the player at the bottom to gain resources in increasingly lopsided games. No good. We need a mechanic for determining who gets to make the first challenge each round.

- Territory decisions. Players are generally asked to agree on where they want to play, and use a roll-off to determine who gets to pick the region if they don’t agree. This isn’t ideal – it reduces a lot of the tactical aspect of determining where to fight to a coin toss, and also basically ignores the map, allowing players to fight battles for territories on the other side of the map from their power base.

- Lopsided games. While Age of Sigmar probably handles these better than 40k, many games in Firestorm are likely to have players matching up with uneven forces. This can mean that with the right draws, even early on a player can find themselves outmatched by a hundred points. While uphill battles can be good if you’re trying to do something like smash an enemy stronghold, having regular battles be uneven doesn’t seem desirable.

- Snowball Effects. There’s no restriction on challenging players for their territory and the bonuses you get for winning mean that a player who wins several games in a row early in the campaign is likely to build an insurmountable lead, frequently coming into games with 500+ points more than their opponents. While you want some momentum effects in a campaign like this to allow winning teams to break through, you also don’t want the entire campaign to be over because one player got too much power too early.

- Kingmaker issues. The ability to deal and give resources to other players can create “Kingmaker” problems, where one player in a losing position can just decide to give all their resources to another player, ceding the campaign and giving that player a boost that other players can’t compete with.

- Build Points Don’t Do Enough. Build points are a neat mechanic but they don’t go quite far enough — there isn’t enough of a mechanical connection between what I’m building and how it benefits me. Players want to have more tangible benefits tied to regions rather than abstract benefits that reflect a structure that could be anywhere.

- No “catch-up” mechanics. Similar to the snowball effect, not having a mechanic for catching up means that players who get behind will tend to stay behind, and find themselves in a position of either getting steamrolled repeatedly or dropping out. That’s not good. That said, the alternate win condition does give players some way to get around this.

Overall, the online reviews I’ve read for Firestorm are positive, and the firsthand recounts I’ve gotten from other Goonhammer authors is that the campaign they ran with it was fun, but quickly snowballed out of control as the Sigmar player steamrolled everyone. Possibly worth looking into if you can find a copy and have a play group who’d be into it.

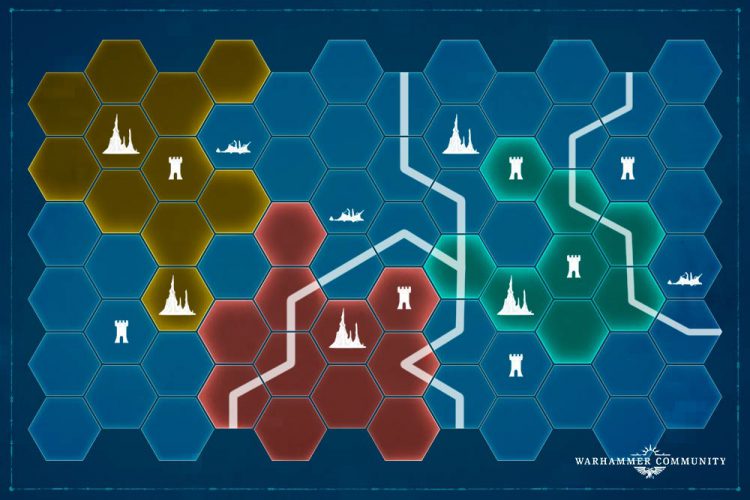

Streets of Death Campaigns (Warhammer 40,000 Urban Conquest)

Not to be outdone, Warhammer 40,000 also got its own map-based campaign expansion in early 2019: Urban Conquest. Rather than focus on a broad map spanning a whole planet, Urban Conquest has players fighting over a single massive city, attempting to conquer it block by block. In addition to a city map, the box also included a series of Location Cards to build the campaign map with, a set of Strategic Resource Cards to play during games, some Random Event cards, and a set of three Strategic Goal cards that give players additional goals during the campaign. Urban Conquest leans heavily on the Cities of Death rules for Warhammer 40k 8th edition, which add more detailed rules for fighting in urban environments. Unlike the fixed map of Firestorm, Urban Conquest uses location cards to randomly generate maps each campaign, creating a more procedural element.

How it Works

Players start by picking an Army Faction they’ll build their lists from, then they generate a cityscape by shuffling the Location deck, and then placing those in each slot on the campaign map (the box comes with a clear plastic card holder for these). The Locations deck has a series of regular locations plus six Special Locations like the Prometheum Reactor and Orbital Shuttleport that require special resources to assault and necessitate playing a special mission based around that location (these have a predetermined terrain setup). Once locations are set, players generate a Starting Random Event from the Random Events deck, a Strategic Goal, and pick their starting territories. There are multiple layouts players can start with, depending on the number of players they have, and each one dictates a different Strategic Goal.

Each round of the campaign is split into two phases: The Action Phase, in which players play Cities of Death games with each other, and the Strategy Phase, in which players determine initiative, earn and spend campaign and strategy points, seize territory, and generate random events. Urban Conquest is relatively vague on the nature of how games are determined, and language similar to Firestorm is laid out to suggest that players should always accept a challenge and fight battles in the time allotted. There’s no limit to the number of games a player can play per round, though they recommend every player get in at least one. Players win Glory Points for winning a battle during the Action Phase (3), but still score for a tie or loss (1) and score extra Glory Points for killing the enemy Warlord (1).

After games are played, the Strategy Phase begins. The player who scored the most Glory Points during the Action phase wins the Initiative in the Strategy phase, and players progress in Initiative order, scoring Campaign Cards for their held Resources (each resource card has a value showing its worth in Campaign Points), and accomplishing the Strategic Goal. Players then earn Strategy Points based on the values of all locations they currently control (again, these values are on the cards), which they can then spend in Initiative order on purchasing Strategic Resource Cards, which are used for extra effects or to upgrade the locations held on the Cityscape Map. Next, players go in Initiative order capturing a single location, then repeat the process in reverse order. You can only capture a location adjacent to one you already control (including diagonal), and you can only capture one held by an opposing player if you won a game against them in the prior Action phase. Special locations can only be captured using a special Strategic Resource card. If a player has zero locations at this point, they lose 3 campaign points and have to start over with a single location on the map, preferably one that is unoccupied. Finally, players generate a new Random Event to apply to the next round of the campaign.

Urban Conquest comes with rules for Cities of Death Games, plus more than a dozen missions, giving players both matched play Cities of Death game options that can use either Eternal War or Maelstrom/Schemes rules (these are pretty good missions, generally), a set of special Narrative missions reflecting certain situations, and a set of special location missions that reflect battles taking place over specific locations like the Saint’s Basilicum and require specific terrain set-ups.

What It Does Well

Urban Conquest clearly takes a lot of lessons from Firestorm and applies them to great effect. The supplement improves on a number of good ideas and adds a few of its own.

- The Cities of Death Rules are pretty good. Urban Conquest stakes a lot on the Cities of Death rules, and it’s good for them that the rules are pretty strong. The changes to the cover rules are a significant improvement over 8th edition 40k, and additions such as -1 to hit obscured targets, hard/soft cover distinctions, and bonuses for firing on units from above make terrain matter significantly more.

- Good rules for capturing territory and managing wins. The “capture a maximum of 2 territories per round” mechanic, coupled with the mechanics for Glory Points, help cap a player’s advantage for winning games in a round and advantages players who play more games without getting out of hand. The game also has a mechanic for ensuring that eliminated players get to stay in the game and attempt to claw their way back or play spoiler.

- Location upgrades. Location upgrades are a cool idea, allowing players to improve their territory and make it more difficult to capture. This is a key element of map campaigns and the way it’s implemented here creates some small bonuses that feel tangible but don’t break the game.

- Procedurally-generated maps. Every time you play an Urban Conquest campaign, the map will be different, creating a dynamic experience each time you want to start a new campaign.

- (Somewhat) Game-agnostic. Although the core missions and Cities of Death rules are designed for Warhammer 40k, the book includes some ideas and suggestions for applying the city map to games of Kill Team, and you could likewise apply the broad mechanics to any game with a few modifications. You could also probably do something similar with Necromunda, if you really wanted. Though Necromunda has some better options already.

- Location Missions. The Location missions are a pretty cool idea, and a great way to make a game actually feel like it’s being fought over a specific location on the map and not just another abstract representation of a campaign asset.

- Blank Cards. There are a few blank cards you can use to create your own locations. That’s pretty great!

- Connection to Planetary Onslaught. The “Taking Streets of Death Further” section is chock-full of great ideas, including a few on how to use the blank cards and how to combine Urban Conquest with Planetary Onslaught, going from a Planetstrike campaign into a Stronghold Assault campaign into Cities of Death. This is pretty neat, but it essentially tacks a map campaign on as the final leg of a linear narrative campaign, since no matter how forcefully the defenders repel the attackers in Phases I and II, they’ll still end up in the cities at the end. It would be cool to have a more malleable narrative, but there are some ways to do that we’ll get into later.

What It Doesn’t Do Well

While Urban Conquest improves on Firestorm, there are a few areas where it still leaves a bit to be desired, and doesn’t work particularly well.

- Not Enough Map Variety. The map in Urban Conquest is, on the whole, good. And the random aspect of it is also good. But the map is always the same 5×5 grid, designed for 2-4 players, and that means that even shuffling the locations likely won’t make the game feel significantly different. There’s also no aspect of discovery – it’s very city-focused (understandably), and would need real work to adapt to more locations.

- Location Missions. Location missions are a double-edged sword: They’re certainly interesting, but they require specific layouts (and Citadel terrain kits), and they’re always the same mission, which can make them tedious if you play them multiple times over the course of a campaign. This can also make them expensive to play, or lock players who don’t own the kits out of playing them.

- Complexity. The Cities of Death rules are, on the whole great. The core rules, anyways. In addition to the core rules, the game mode introduces an extra 21 stratagems, of which most are either bad, extremely situational, or tie directly into a specific Citadel terrain kit, plus another 6 Key Building Stratagems that upgrade a building. This is a lot of extra cruft the game doesn’t really need added on to an already bloated stratagem pool. This could have easily been cut down to a single page of 6 stratagems: Point-blank Overwatch, Breaching Gear, Hunker Down, Wrecker, Grappling Hooks, and Demolitions.

- No Narrative. Unlike Firestorm, which builds around a particular campaign narrative, Urban Conquest is just kind of generic, and as a result the story is incidental. Yes, this will naturally tie into the campaign being modular and procedurally-generated, but it would have been helpful to have content that talks about expanding it for a particular narrative.

- No Alternate Win Conditions. One of the more clever things Firestorm did was have an alternate win condition for the campaign. It would have been cool to see that at play here — the Strategic Objectives giving bonus points is nice, but it doesn’t quite have the same feel as “securing the mystical doodad and claiming the points of power.”

Overall Urban Conquest is a pretty clever map campaign resource for players. It comes bundled with some terrain, which is kind of weird, since it inflates the cost and box size without offering much you’d actually need. It also repackages a number of rules from Chapter Approved 2018, though there’s enough new stuff here – especially the Matched Play Cities of Death missions that weren’t in Chapter Approved. This is a pretty solid template if you just wanted a quick-and-dirty map campaign setup, and there’s a ton here I’d recommend stealing if you’re planning your own map campaign.

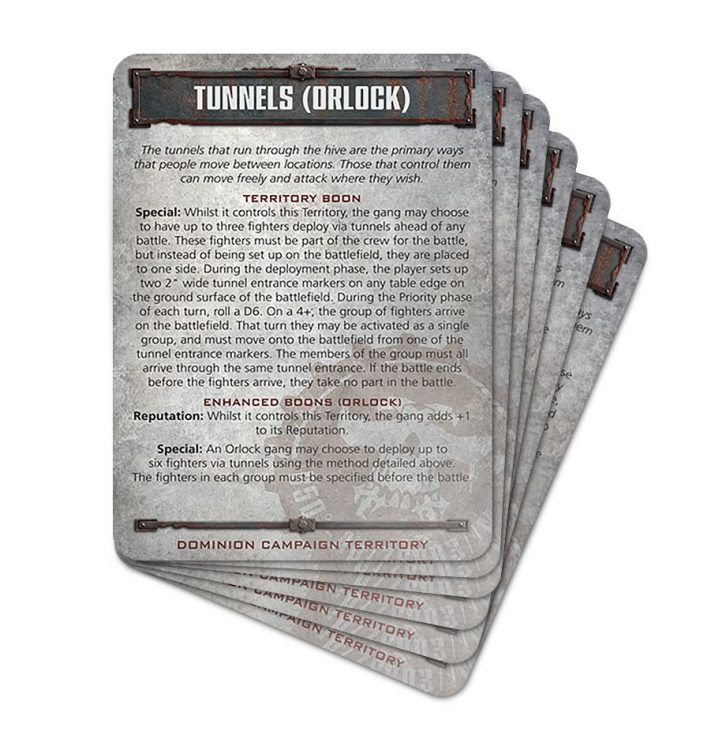

The Dominion Campaign (Necromunda)

Introduced in Gang War IV, the Dominion Campaign and folded into the second edition of the Necromunda rulebook, the Dominion campaign is based around gangs fighting for control of territory in the underhive, with every battle fought over the control of a specific territory at stake. Holding a specific territory grants the gang controlling it a benefit called a boon and the campaign lasts a specific amount of time, after which the winner is determined based on which gang controls the most territories, has the most rep, resources, and how many enemies they’ve taken down.

For a more tactical view of the Dominion Campaign’s assets, we’ve compiled a ranking of all of the Dominion Campaign territories here.

How it Works

In a Dominion campaign, players use the Dominion Territories deck, a deck of cards where each card represents a specific territory for gangs to fight over and claim in their quest to dominate the underhive and expand their turf. At the start of the campaign, the Arbitrator generates a number of territories based on the number of players in the campaign and reveals a number. Then players challenge each other to fight battles over the revealed territories, with each game having one territory at stake that goes to the game’s winner. After all the revealed territories have been claimed, the Occupation Phase ends and the Downtime Phase begins, during which gangers recover, captives are returned, juves are promoted, and new gangers are recruited. Once that ends, the Takeover phase begins, in which players challenge opponents for territories they wish to seize and fight battles over held territories.

Each Terrain card has a unique effect that can apply to the games a player plays, with a variety of effects and bonuses if they happen to fall into specific gangs’ hands – some territories are just a better match for some gangs than others. At the end of the campaign, players are awarded titles for having the most territories, reputation, fighting the most battles, taking the most fighters out of action, and amassing the most wealth.

Note that the Dominion campaign doesn’t technically use or need a map, and it runs perfectly fine without one. But you can certainly give it one, and assign territory cards to the map you’re working with, either ahead of time, or dynamically allowing players to add territories to an expanding map as they’re claimed/discovered. In a Dominion campaign, any maps you add are completely aesthetic additions, and useful only for visualization. Still, the core concept of collecting and holding territories is very reminiscent of what map campaigns want to do, even if it lacks a physical map.

What it Does Well

There’s a reason the Dominion campaign is the default Necromunda campaign in the core rulebook. It does a lot of things well, and it’s easy to run:

- Easy to run. Everything you need for a Dominion campaign is in one place and the rules cover a few pages. The cards make understanding what territories you control and what their benefits are very easy.

- Combines with other campaigns. You can combine/stack the Dominion campaign with other Necromunda campaigns like the Law & Misrule campaign or the Dark Uprising campaign, adding an extra layer of craziness to your campaign.

- Territory limits. Because new territories are revealed each round and players can only play until all the territories are claimed in the Occupation phase, and whatever you can win from other players in the Takeover phase. This essentially limits how much territory a gang can claim in a given round.

- Separate claiming and capture rounds. Separating the claiming territory and capturing territory rounds is pretty smart – it allows players to get multiple chances to get territories, and players aren’t forced to challenge other players for their territories if they don’t feel up to it.

- Natural risk mechanics. This isn’t part of the Dominion campaign per se, but Necromunda has natural risk mechanics built-in during a round – injuries make it so a player is less likely to play a ton of consecutive games each round before healing and recruiting happens.

- Multiple goals. Dominion campaigns don’t produce a single clear winner. At least, not unless one gang manages to win every award. Instead, the awards give players different goals to strive toward, and there are lot of consolation prizes.

What it Doesn’t Do Well

That said, there are a few things about it that aren’t so great:

- No game caps. There’s nothing limiting how many games a player can play per round outside of the injury mechanics catching up to them, so a very lucky player could get out to an early lead that gets them way ahead, amassing more credits from their empire.

- No catch-up mechanics. Conversely, a player could get completely destroyed early on with some bad luck and struggle to catch up.

- Territories vary wildly in power. While the territory cards are very cool, they also vary wildly in power level from “so good you should try and own this immediately every campaign” to “this is complete trash and if you end up with it you should get rid of it.” That can mean that fighting over territories you don’t really want.

- Challenge-based. Games Workshop really loves to have rounds revolve around players challenging each other. Again, there’s no priority for this, so it’s whoever challenges each other first, and there’s nothing stopping a strong player from challenging a weaker one repeatedly, and either beating up on them or getting free territories if the challenge is refused. This mechanic really wants Arbitrator intervention.

- No clear winner. While the Awards system is neat, if you did want a clear campaign winner, you’ll need to do some work on your own to determine it. This probably goes against the spirit of Necromunda but on the other hand, the goal is total hive domination.

- Scenario generation. The Necromunday boys have talked about this a lot, but the standard scenario generation tables for Necromunda are pretty bad, and can lead to playing the same scenario over and over. Fortunately, we’ve offered a few solutions to this issue.

Titandeath Map Campaigns and Subsector Map Campaigns (Adeptus Titanicus)

I haven’t played with these rules yet, so I asked Condit, our Warlord Wednesdays head writer, to give a rundown of these rules.

Adeptus Titanicus has its own map campaign systems, and has been plugging along with these for some time now. The Titandeath expansion in 2019 introduced rules for campaigns to Adeptus Titanicus that allow you to command your legion as it fights for control over a planet and its resources at the height of the Horus Heresy. Later, Shadow and Iron expanded on this, adding more rules and letting you take expand your campaign to cover an entire subsector.

How it Works

Both campaigns are fairly standard map campaigns, and they function similarly to how you’d expect a map campaign to run – each round players determine an attacker and a defender, then the attackers declare the territories that will be the target of their attacks, and more than one attacker can choose the same territory. Defenders then choose territories to defend or neutral territories to claim, and more than one defender can choose the same territory. Then players play a battle for each territory containing attackers and defenders, and the winners get control of the territories they were fighting over. Undefended territories are automatically claimed. In order to incentivize defense and spread out attacks, players attacking undefended territories can choose to Raze them, reducing their value.

As players win terrain, they gain Armoury points that can be used to effect repairs, refit titans, and build reinforcements. They can also improve their territory over time. The sub-sector campaign rules from Shadow and Iron are a bit more involved, but either provides an interesting and immersive backdrop for your Titanic battles. Players will muster their battlegroups and move across the map, build and scavenge for reinforcements, and manage losses as they vie for dominance over whatever unfortunate chunk of rock they happen to be fighting over.

What it does well

These rules are neat because they do a few things that the other map campaign systems don’t, adding their own advancement rules and having a team pay aspect with the loyalists vs. traitors rules.

- Battlegroup Advancement. As you play games and win victories, you’ll have the opportunity to expand your battlegroup, adding new Titans and opening up additional strategies. On top of that, your Titan crews can gain experience and new abilities, and your Titans will be outfitted with new and unique weaponry and wargear as they advance through the campaign.

- Team Coordination. Since you’re splitting into loyalists and traitors, you have the opportunity to work together with your teammates to seize victory and defeat the other side, and you’ll need to work together if you want to win. Rather than presenting you with an “every player for themselves” situation, AT’s campaign rules encourage you to coordinate with other players for your mutual benefit, which can be a lot of fun.

- Fluffy and Flavorful. Each objective in an AT game has unique traits that make it worth fighting over: whether you’re fighting over a hive spire or spaceport in a planetary campaign, or contesting an entire forge world in a sub-sector campaign, every move you make will feel meaningful. Plus, in a sub-sector campaign, each individual world winds up being different from the other worlds of the same type due to unique traits and environmental effects that both impact its strategic value and impose various effects on your battlegroup as you fight over it.

- Persistent Narrative. Titans don’t just gain experience and wargear, they also suffer damage and losses that will need to be repaired or replaced. If you take a bad loss, your battlegroup will still be feeling it into the next campaign round. This can be incredibly punishing, but also lends additional weight to every decision you make – if you mess up, it’ll come back to haunt you, but a lucky shot could have an impact not only on this game, but on future ones as well.

- Scorched Earth Mechanics. The ability to raze undefended terrain really helps ensure players spread out their attacks broadly, and that defenders rush to the defenses of their territory.

What it doesn’t do well

There are a few things that these rules don’t do so well:

- Limited catch-up mechanics. As with some of the other campaigns here, it could be difficult for a player who gets a few bad beats in early games to catch up – being unable to reinforce your battlegroup can be crippling, and a dead Titan crew can’t gain experience.

- Territories and planets vary in power. While not quite as drastic as some of the other systems here, the differences in various territories can make a huge difference in how much your players will have to work with. The planetary campaign balances this a bit by giving each player a fixed set of starting territories, but the sub-sector campaign is entirely random, which could lead to some rough starts depending on how the dice shake out.

- Only Two Teams. As it’s the Horus Heresy, you’ll have to divide up into two factions: Loyalists and Traitors. While this makes defining a winner a bit easier as you’re only looking at the combined points for the faction, it also means that you’re somewhat limited out of the gate. Individual players can switch sides over the course of the campaign, but it gets kind of weird and will require some work on the part of the GM to make sure it goes off smoothly.

- No Scenario Generation. The rules for generating scenarios for campaigns are very thin, and AT’s matched play rules can get repetitive after a bit. Your GM and players will need to get creative to keep things interesting over the course of a campaign and differentiate later games from those that come earlier on.

The Planetary Empires Campaign (5th Edition Warhammer 40,000)

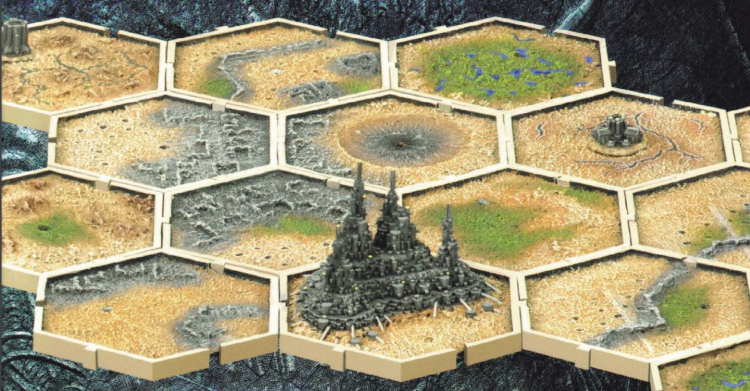

Introduced late in the lifecycle of 5th edition 40k, Planetary Empires (and its sister publication, Mighty Empires for Warhammer Fantasy Battles) wasn’t the first 40k campaign supplement (Cityfight has that claim), but it was the first map-based campaign supplement for Warhammer 40k. In Planetary Empires, players battle over a map of hexes that come packaged in the campaign box, with captured hexes giving players various bonuses and abilities. Players compete to be the first to control an empire of 10 tiles.

How it Works

A Planetary Empires campaign starts with one player or a GM building the map by randomly snapping tiles together until an appropriately-sized map has been created (the rules recommend 6-8 tiles for each player – the box came with 48, allowing campaigns of up to 8 players). Once they’ve done this, each player claims their starting tile by placing their banner on the tile they want to control, and players go in order repeating this process with tiles adjacent to one they control until all tiles have been claimed.

Planetary Empires campaigns are split into Campaign Rounds, during which players organize games against each other of any size they want, and play as many games as they want. When these games are played, players receive bonuses in the form of Bonus Points for things like having fewer tiles than their opponent (holding more tiles indicates that your army is stretched thin over a larger area). These bonus points can be either added to a player’s army, used to take mercenary units from another faction, or take allied units from another player. At the end of each round, a player can attempt to claim a tile from a defeated opponent, starting with the player who controls the most tiles. Capturing tiles requires a 2D6 roll of 3+ if the tile is adjacent to one of the winning player’s tiles or a 7+ if it is not, and several things can modify the roll in a negative fashion, such as the tile having a mountain or space port, or if the victory is only a “moral one” (this was determined by 5th edition mission rules). Players can also attempt to capture multiple tiles, but incur a -1 penalty for each tile after the first.

The tiles themselves contribute to a player’s resources as well. Pieces like Power Stations, Shield Generators, and Manufactorums give tiles additional value. These structures give their controlling player a Bonus Point bonus that varies based on the player’s faction, with different factions benefiting in different ways.

What it does well

Although it’s nearly 20 years old at this point, there are still some very interesting things about Planetary Empires that are worth considering. It’s unfortunate that Games Workshop didn’t think this was an area worth more expansion.

- The cool map tiles. The physical, 3D map is pretty damn cool. It’s a hobby project in its own right, and there’s something that just owns about having a bunch of physical tiles to look at for your map. I’ve seen players do some great stuff with these, including making maps that feature several planets (represented by groups of tiles in circular groups). They also offer cool ways to convert up things like multi-tile mega hives and represent all kinds of neat stuff. The whole thing just looks awesome.

- Procedurally generated maps. The random construction of maps means that no two games are the same, and layouts can vary greatly. You can do all kinds of narrative things with the tiles, like the aforementioned multiple planets approach, or paint them differently to create water/ocean tiles, ice wastes, deserts, volcanic flats, and so on.

- Capture limits. While it’s not a ton, the capture mechanic is interesting, adding some (manageable) randomness to the capture mechanic and making it more difficult to capture multiple locations. It also makes positioning matter in a way that not every map campaign ruleset doesmore .

- Faction distinctions. There aren’t a ton of rules for the factions in Planetary Empires, but it’s neat that not every resource type benefits all factions equally. It creates some interesting incentives and objectives for different players that’s a neat addition.

- Strong tile distinctions. There’s a clear, obvious difference between different tiles/territories, and it’s not just visual – each of the major structure types has different advantages and disadvantages, and makes them more difficult to capture than a standard piece of territory. The Spaceport letting you capture non-adjacent tiles without penalty is a particularly strong touch.

- Rules for a player losing all their tiles. There’s no “home base” tile for a player, so if they lose all their tiles, they stay in the game, but they can’t have tiles claimed from them anymore. Having a way to handle this is good, even if I don’t love this implementation.

- Rules for adding new players/players dropping. Planetary Empires includes guidelines for what to do if players drop from the campaign or if you want to add new players mid-campaign. That’s a great thing to have, and acknowledges the reality of running a campaign.

What it doesn’t do well

Planetary Empires is an early attempt, and it’s really rough. The rules are more a pamphlet than a real rulebook, and if you were to argue that the thing is more designed to sell plastic tiles than be a full campaign system well, I’d have a hard time rebutting you.

- Too much emphasis on the tiles. Look, the tiles are great, but they’re really just an aesthetic representation. And putting too much focus on them means that if you did want to do something around this nowadays, you either have to scour ebay for expensive OOP tile sets, or make your own. The good news is, making your own hex map is pretty easy.

- No rules for who plays and when. With no limitations or structure around who can play and when, a Planetary Empires campaign can end up a little lopsided, particularly if one player can keep beating a weaker player to get ahead. It also means that, while there are rules for a player with no tiles, there’s no particular reason for a player to play against that player or accept their challenge, since they have nothing to gain by doing so. This is a challenge all map campaigns must reckon with.

- Balancing/Catch-up Mechanics. The extra points a player gets for having fewer tiles is both a great way to balance things and thematically appropriate, given how they’ve explained it in the rules. It’s usually going to be offset by the special territories a player controls, but it’s a good way to keep things pretty even. Also the capture mechanics making it more difficult to capture a tile based on what it has helps make defense of key tiles meaningful.

- No home bases. Although players start with territories in Planetary Empires, there’s no real distinction in the tiles themselves, and there’s no “home base” tile for a player. That’s a bit of a missed opportunity, and means that taking a player’s last territory is the same as taking their first.

- No terrain improvement. While tiles in Planetary Empires can have buildings on them, you can’t add to them or improve them. That’s a bit of a missed opportunity. Note that the rules mention building new structures, but doesn’t provide rules for how to do this – it’s left up to players to create a system. That sucks, because it’s a pretty complicated mechanic and it needs a bit more thought given to it than just “hey this will be fun to figure out on your own!”

Other Systems

Of course, these are just the systems related directly to Games Workshop games. There’s a whole host of map campaign assets for other game systems out there. One of the most common terms for these is “hex and counter” games, because of the map assets they use. These can get pretty complicated, but if you’re interested in exploring them more, I’d recommend heading over to reddit, where the r/hexandcounter subreddit is a great resource for these. I’m not directly familiar with any of these but one day I may convince Lupe to talk about them on Goonhammer, since he’s a million years old and plays historicals.

Creating Your Own Map-Based Campaign

Up to this point we’ve spent a lot of time talking about what’s out there, and what we can learn from it, but what if you want to build your own campaign system? One that takes from those and doesn’t repeat their mistakes? Well in this section I’m going to talk about how you can do just that, and the things you need to keep in mind while making a campaign.

Things Your Campaign Needs

Map campaigns are complicated. They don’t have to be extremely complex, but by their nature, they need a lot of rules that more linear campaigns don’t. If you’re making your own map campaign system, you need to make sure you have the following:

- A map, with multiple territories outlined on it. The more players you have, the more you’ll need.

- Rules for how players determine their starting positions. Also what territories, if any, they’ll start with.

- Rules for how players acquire new territory and lose territory to other players. Ideally, you’ll limit the advantages a player can get for playing more games than another player, and at the same time, give players an incentive to play games.

- A system for handling unclaimed/unowned territories. Do these just get claimed? Do players have to fight over them? If you have unclaimed/unexplored territory, you need a system for determining how players will gain control of it.

- Rules for how players challenge other players (or are matched), and how to resolve disputes and timing. Initiative systems are great for this, but a GM/Arbitrator can also assign matches if need be.

- A goal or endgame for players to work toward. Players need to know how they’ll win your campaign. This can be as simple as “we’ll play X rounds and at the end whoever has more territories is the winner.”

- Rules for how to handle players dropping or losing all their territories. Ideally this doesn’t just boot players out of the campaign, because it really sucks when you get kicked and all of your friends are buys playing games for the campaign you’re no longer in.

- A set of limiting rules or comeback mechanics to prevent the campaign from becoming a foregone conclusion if one player wins a few games early on.

Things That Are Nice to Have

In addition to those things you have to have, here are a few things that in my experience make for a better map campaign:

- An Arbitrator or GM. These things run much better if you have an arbitrator/GM to manage disputes and set scenarios. Ideally they’re impartial, but it’s OK if they’re also players. GMs can also dictate mach-ups and create campaign events.

- Territory Distinctions. You want the territories to matter beyond just being assets for players to control and count. Having rules for the battlefields and having special bonuses for specific terrain assets/types really makes the map matter beyond just being a thing you look at between rounds.

- Terrain Improvement. Giving players a way to improve their terrain helps them feel like it’s actually theirs and raises the stakes for battles that take place over that territory. This can be as simple as “improve one territory per round of your choosing” or can involve complex resource systems.

- Home Bases. I’m a big fan of having home bases for players. They give players a central location to expand from and can create some cool narrative moments around a player desperately attempting to fend off an attempt to capture their base and run them off the map, and can lead to some daring

- Custom Mission Rules. Another way to make terrain matter is to apply battlezone rules or special missions to battles being fought over it. These help mix things up and really make the map aspect feel real. I’ve already talked at length about battlezones in 40k and which ones are good – check that out here.

- Alternate Win Conditions. These provide some extra drama during a campaign and can help players who fall behind on controlling territory catch up.

- Multiplayer Rules! Something that all of these systems somehow left out is how to handle a situation where more than 2 players want to claim a territory. I’d recommend shoring this up and having ways to resolve having 3+ players fighting over the same territory. This can be as simple as a 3-player game, or you can work something else out.

- P R I N T E D M A T E R I A L S. I’m a sucker for printed cards and other asset markers that make it easy to know what you have and when. You don’t need these, but they’re very cool, trust me.

Things to Avoid

Finally, here are some things you want to make sure you don’t do when designing your map campaign system:

- Too many bonuses. Keep bonuses small and try to make them easy to remember. Even if your players are into it, if you’ve got too much stuff to track between games or as bonuses, your players will quickly forget about it and then it’ll all be wasted work.

- Too many resources. Gold. Minerals. Prometheum. Morale. Requisition. Power/Energy. Strategy Points. There’s a lot of stuff you can use as a campaign resource for spending but I’d caution against having more than one to keep track of and spend. It’ll quickly make things a real chore to manage and track.

- Too much complexity. As a general rule, try to keep things as simple as possible. The more you add on, the more likely some of it will be forgotten or left by the wayside.

- Lopsided games or tying too much to terrain. Giving players army points bonuses for controlling territory or tying any advantages too heavily to terrain will ensure that the players who are in the lead get out to further leads, leading to snowball effects that cause the campaign to end early. You want to avoid these.

- Too much narrative focus. It’s important to remember that the campaign is still a game. Make sure you have a balanced experience planned for your players and don’t focus too much on the in-universe backstories. If you’ve got 4 Order and 2 death players, find a reason for your Order players to split up or have one ally with Death. Having a good experience is more important than staying accurate to the game’s lore, and there’s really nothing in the 40k or Age of Sigmar universes that can’t be justified somehow.

- Reinventing the wheel. If you aren’t publishing this to make money, no one is going to care that you took elements from another game, or even the map and card assets. Steal everything you like from anywhere you can get it, then fill in the gaps for the rest. What matters is creating a fun experience here, no showing off your game design chops. You’ll have plenty of opportunity to show those off in the process regardless and all at the end all people are going to remember is whether they had a good time.

Go Forth and Conquer

Generally, my recommendation is that you start by taking one of the systems above and modifying it to fit your needs. Trim out the parts you don’t like, add the parts you do, and go from there. There’s no reason to reinvent the wheel here, and the systems we’ve already seen do a lot to really showcase how flexible you can be when it comes to map campaign rules.

This pretty much finishes off my long-running series on campaigns. We’ll be doing some more work around campaigns in the future, as Alice “RagnarokAngel” Lirette will be reviewing the Age of Sigmar campaign supplements and I”ll be offering some more campaign assets and templates, but for now I’ve said pretty much all I have to say about campaigns without just pushing out more Goonhammer Approved content. I’d like to give a big thanks to everyone who asked for help while I was working on this or gave suggestions, and as always if you have any questions or feedback, feel free to drop a note in the comments or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.