There’s a through line in Ted Lasso, most notably in Season 1, Episode 8, involving sense memories, hobbies, and ones relationship with their father. For him, it’s BBQ sauce. For me, it’s the smell of wood and a leather couch in the condominium in Utah my father had owned since he was in college. He’s on a business trip, and he’s taken me with him.

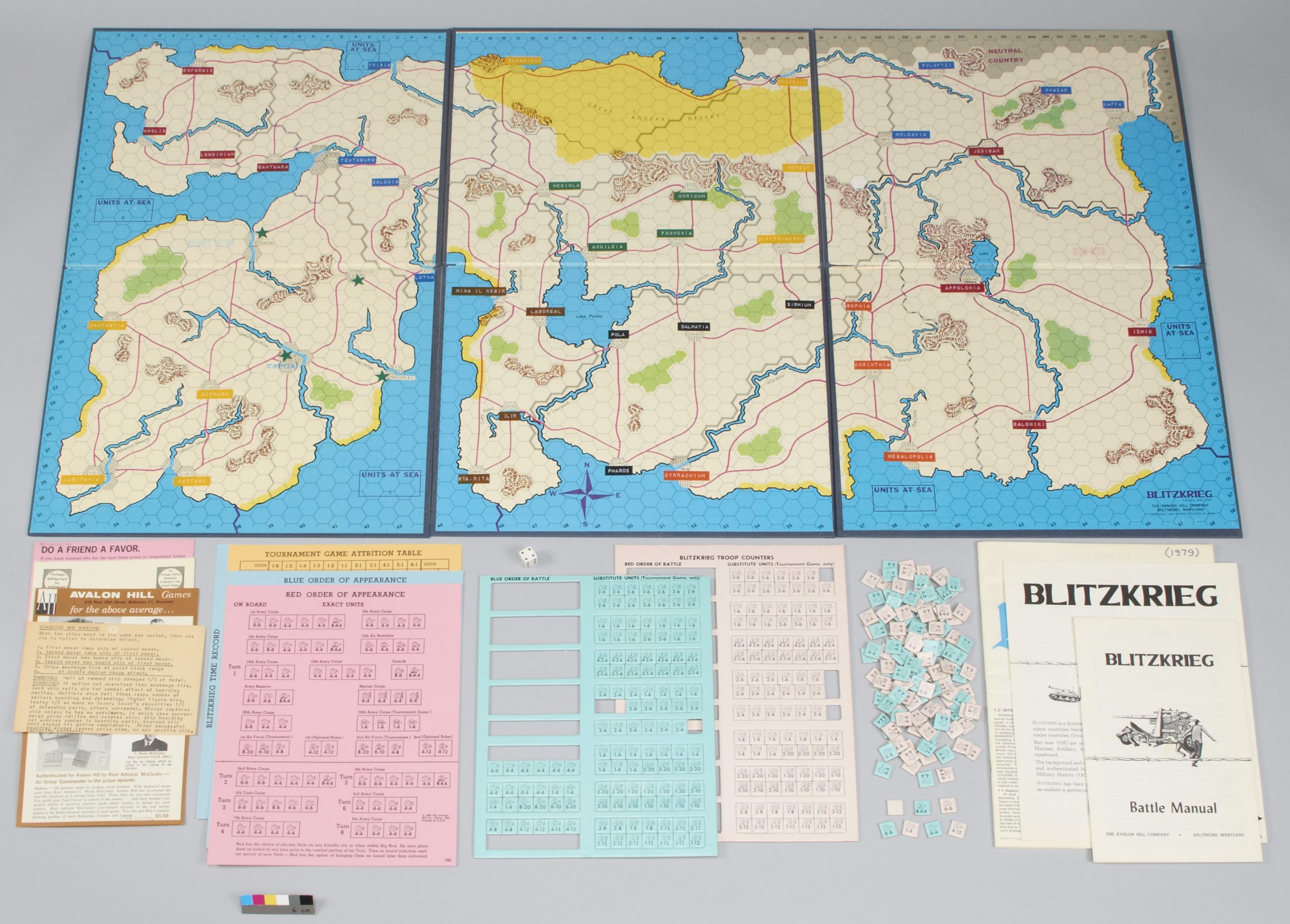

I’m nine, maybe ten years old. We’re playing Blitzkrieg. I’m playing “Blue” as is my preference to this day, and thanks to the combination of the Blue Marine Corps plus the “Great Koufax Desert” meaning I can land those troops almost anywhere on the northern edge of the map, I have accidentally invented the concept of a “fleet in being” – though I won’t learn the name of it for the better part of two decades.

But demands for shoring up another flagging battle demands the deployment of the marines, and absent the threat of them landing behind the “Red” advance and cutting off their supply lines, the northern front collapses, and by the end of the night, Blue has surrendered. My dad explains what went wrong as we fold up a well-worn game board and put small pile of blue and pink square cardboard tokens back in little plastic bags.

This is how I got into hex-and-counter wargames.

I want you to join me.

What Is a Hex-and-Counter Wargame?

Hex-and-Counter, or sometimes Hex-and-Chit or a number of other names, are a classic, and now extremely niche genre of wargame. Arguably some of the very first wargames, like Kriegspiel, fall into this category.

While we often think – and talk – about hex games (which I’m going to call them from now on for brevity), we’re often invoking objects from the past. Half remembered boxes on the bookshelves of parents or relatives, games that went out of print before a lot of the readers of Goonhammer were born. Inherently something from the past.

Equally, we often think of wildly complex games – like the near legendary Campaign for North Africa or Starfleet Battles. Games whose devotion to the simulation of military combat render them nearly unplayable.

Both of these reputations are honestly well deserved, but don’t really capture the full picture of what’s out there. And while there are some games perhaps best left on those dusty, half-remembered shelves, there’s some others that are worth your consideration.

Why Bother When We Have Miniatures?

Miniature wargaming, while a niche hobby all its own, definitely ate hex games for lunch. There are no publicly traded hex game manufacturers, let alone ones on the FTSE 100. The leaders of the industry in its heyday, Avalon Hill and Simulations Publications Inc. (SPI), were acquired essentially for their IP by Hasbro and TSR respectively, and have, for all intents and purposes, vanished.

And let’s face it, miniatures are quite cool.

But as much as the aesthetics of miniatures games can carry them quite far, there’s a different, but never the less quite pleasant visual and tactile experience to a well-designed hex game. Moving little stacks of counters around has it’s own kind of charm, and the maps involved are often lovingly detailed works of genuine art, especially if you like a good map.

I was in the state finals for the Geography Bee back in high school. I love a good map.

In retrospect, these two things might be related.

But beyond a different aesthetic experience, there’s also a gameplay aspect which we’ll go into more: you own the game, not an army for the game.

The Best Parts

Asymmetrical Conflicts

Let’s get into that last sentence in a little more detail. Miniature wargames are often (though not exclusively, especially in the historicals space) somewhat confined by the notion of a “balanced” game – that I should be able to show up with my army, and you should be able to show up with yours, and we should both have a reasonable chance of winning.

While narratively things like doomed last stands, desperate gambits, etc. are wildly compelling, actually getting people to play asymmetrical games is a tough challenge.

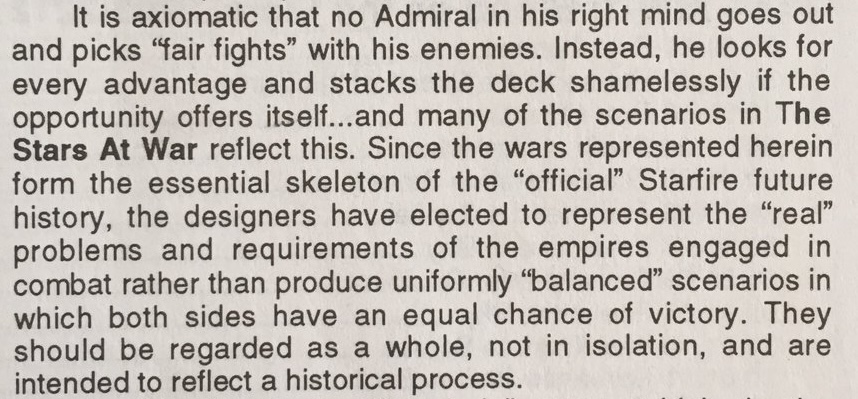

Hex games, in contrast, do this very well. Indeed, it’s often baked into the game – recognizing that very few generals go into a fight where their chances of winning are a coin toss, and those that do are, at best, remembered as idiots. One of the introductory passages to Stars at War, a “future history” campaign for the game Starfire, lays this out explicitly:

But because counters don’t represent hundreds of hours of work and hundreds of dollars invested, you can play an unbalanced scenario. And when you’re done? Flip the board around and play the other side. I played a game about the fall of Berlin – in this game, the Germans will lose. It’s only a matter of time. But that matter of time is what they’re fighting for – can you slow down the Soviets enough that the British and Americans take Berlin instead? Between you and your opponent, who wins faster?

Fog-of-War

It’s hard to do proper fog-of-war with miniatures, especially without elaborate setups. In hex games? Counters often have a backside with little/no information. Some games outright include “Yeah, that was a decoy…” counter, or the ability to split units, so it’s hard to tell if that fort’s garrison is three regiments, or three companies.

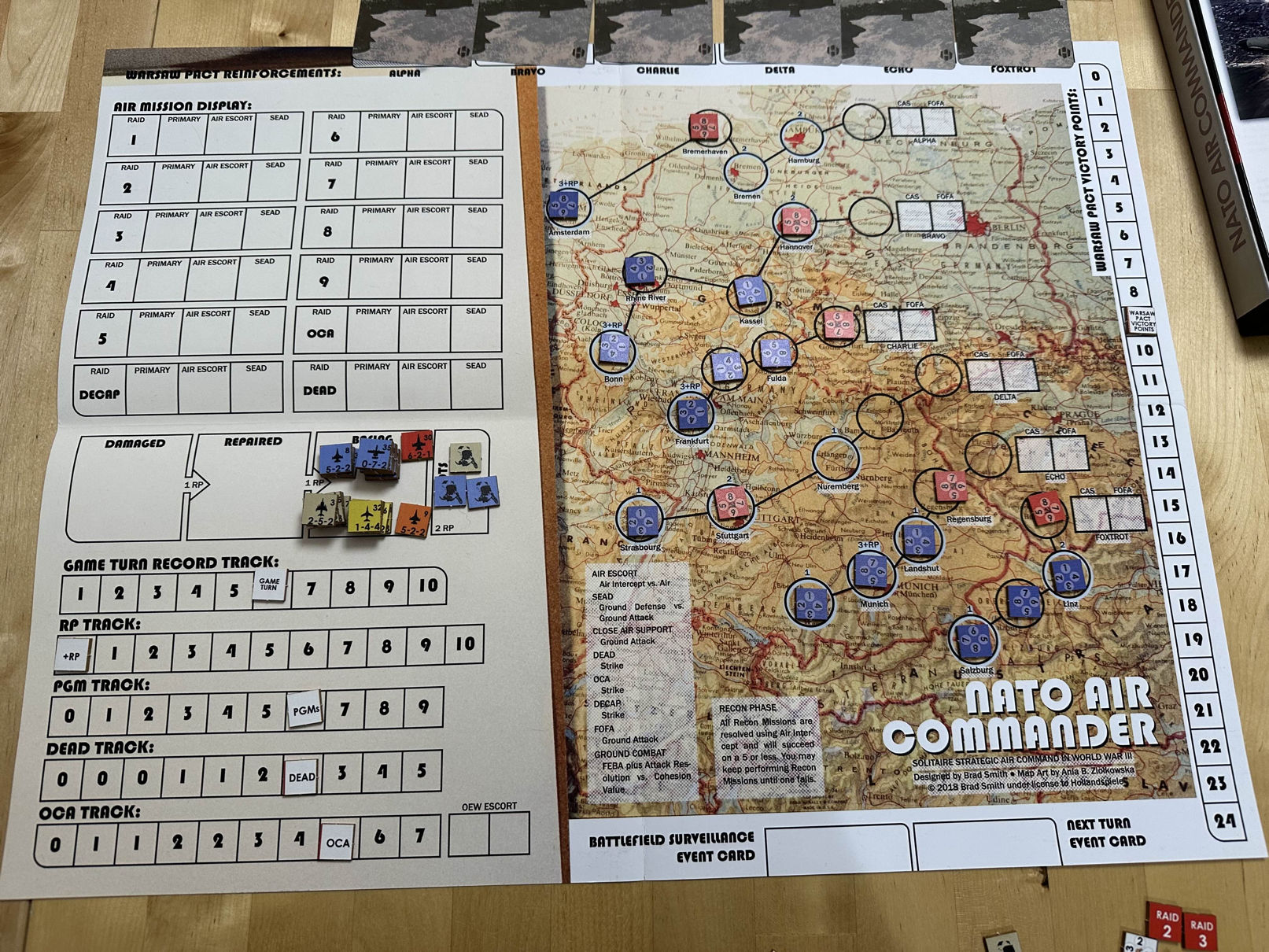

Solitaire Games

While solitaire miniatures games – Silver Bayonet, Five Parsecs from Home, Rangers of Shadowdeep, etc. have a dear place in my heart, hex games have been doing solitaire play for a very long time. Most games are at least moderately capable of being played alone if you can sort of compartmentalize your mind and throw the game for someone. Some are expressly designed to be played solo, and a have mechanics entirely devoted to that purpose.

There’s a peace and a joy in solitaire games – they can be played whenever you please. Often for me that means about two in the morning, with just the dining room light and the fireplace on, listening to the wind and letting my mind unspool from work. If you’re tired – you quit. And if you’re having a game against “that guy”? Well, to paraphrase a colleague of mine, that’s an iss-you.

Scale, Scope and Subject

For all the variety in miniatures wargames, they are inherently somewhat limited in scope. Even smaller scale games, like Legions Imperialis, or the mad lads running 2mm Roman armies, are limited to a single battle. Hex games can range from the very small scale tactical game to operational-scale games representing entire theaters, fronts, or wars. Back in the day, when Games Workshop wanted to make a game about the entire Second War for Armageddon?

They did it with a hex game. Well, not technically hexes, but one in spirit.

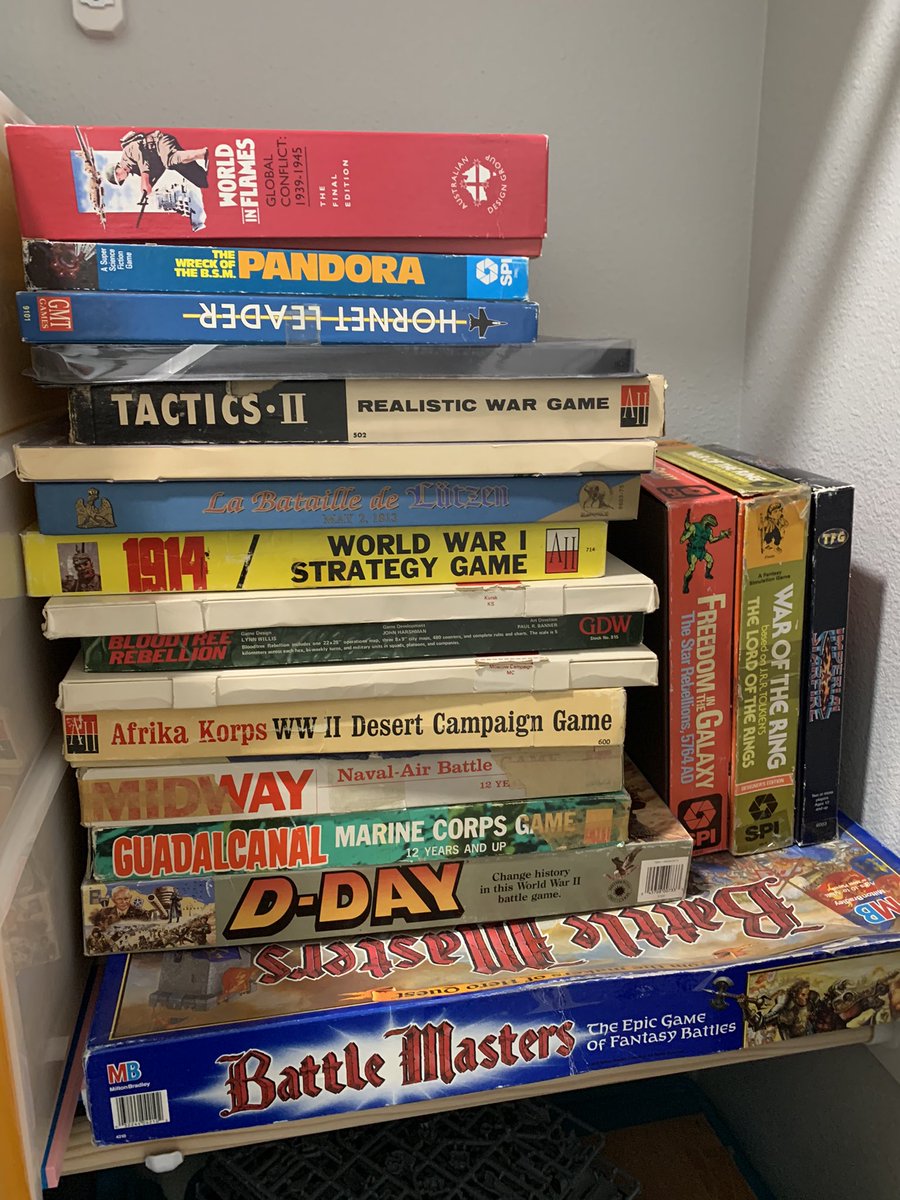

This can get to truly staggering levels, like World in Flames, which covers all of World War 2. All of it. There are literally thousands of counters.

These monuments to game design and/or mankind’s hubris aside, many of these games are also essentially as practical as a skirmish game – meant to be played in an couple of hours, and by design intended to fit on a dining room table. Modern hex games are under the same sort of pressures to fit into people’s increasingly busy lives and be playable.

The final real benefit is that hex games can do a very deep dive into something, where miniatures games might struggle to find the means to justify sculpting, even in this age of 3d printing. There are some very obscure subjects with games about them out there, half-games, half-academic (or at least quasi-academic) explorations of a topic. This results in an amazing amount of variety. Within reach of my desk, I’ve got games about the Cold War from a tactical level, the post-Gustavus Adolphus campaigns of the Swedes in the Thirty Years War, Charlemagne, the Japanese naval campaign against Germany in WW1, the Cold War from the perspective of a NATO air commander, the Cold War from the perspective of the North Atlantic fleets, several science fiction games, a game about Gettysburg, a game about Operation Market Garden, and Meltwater, which helpfully describes itself as:

“…a bleak satire, a compellingly nasty two-player game, and a pointed critique of unchecked military spending in an age where a fraction of that money could end world hunger.”

In case we were worried that interest in these games only comes from one side of the political spectrum.

This variety also lets designers play around with mechanics, explore particular aspects of conflicts, etc. Indeed, there are many successful series of games applying the same sort of mechanical tricks to a variety of topics – GMT’s COIN series about counter-insurgency warfare covers everything from the Russian Revolution in Finland, Vietnam, Marxist Guerrillas in Columbia, and a rebellion on Mars. Oh, and the fall of Roman Britain.

If there was ever a battle near your hometown, or some niche topic you’re interested in…odds are there’s a game about it.

The Not-So-Great Parts

Availability

There’s just no promise you’ll be able to find that game. The hex game market is a brutal one, and one where things are often out of stock, produced by companies that no longer exist, etc.

That Battle for Armageddon game? It’ll be about $150 on Ebay. There are examples far more expensive than that. And often, this just involves sitting on a waiting list waiting for a reprint, or trying to navigate a site that was probably coded when GeoCities was still a thing, and features a rotating “Under Construction” gif. Many of these games are passion projects, produced by a single creator, and available until they aren’t.

There are ways to find them. Noble Knight if you’re in the United States carries lots of new and used games. Ebay is Ebay. But often, if you want a particular game, be prepared for a hunt. And to accept the occasional beat up box.

Community

There are two aspects to this I want to talk about: The absence of a community; and the community that is there.

The first one is a reality of being a niche of a niche hobby. Odds are there is not a thriving hex game scene in your area, or at least not one that’s easy to find. You might have to build it yourself. But this is a familiar thing with any game outside the Games Workshop sphere – sometimes you just have to be the person who builds it yourself. And in comparison to the buy-in for both sides of most miniatures games, a hex game is probably more affordable. I got someone to play Battle for Armageddon with me by just showing up to our club’s normal Friday night game and saying “Instead of 40K, would you be interested in trying this out?” We had a blast, and several other people have expressed an interest.

And again, there are always solitaire games if you’re really passionate about wanting to play something without worrying about bringing anyone along with you.

As for the community that is there…it has a reputation. As much as I’m trying to reclaim the phrase “grognard,” it’s a thing. It’s there, and it’s undeniable.

But I’ll say this – if you’re reading Goonhammer, that same criticism has been leveled at the part of the hobby you’re passionate about. Don’t uncritically accept that that’s just how things are. Communities thrive under active, positive influences. Be that for your community, regardless of whether your little toy soldiers are plastic, metal, or cardboard squares.

Untrammeled Complexity

You know that one player in your club who keeps coming up with homebrew campaign systems, with multiple layers of special rules, a character advancement table, a unit attrition table, seasonal weather effects, etc.?

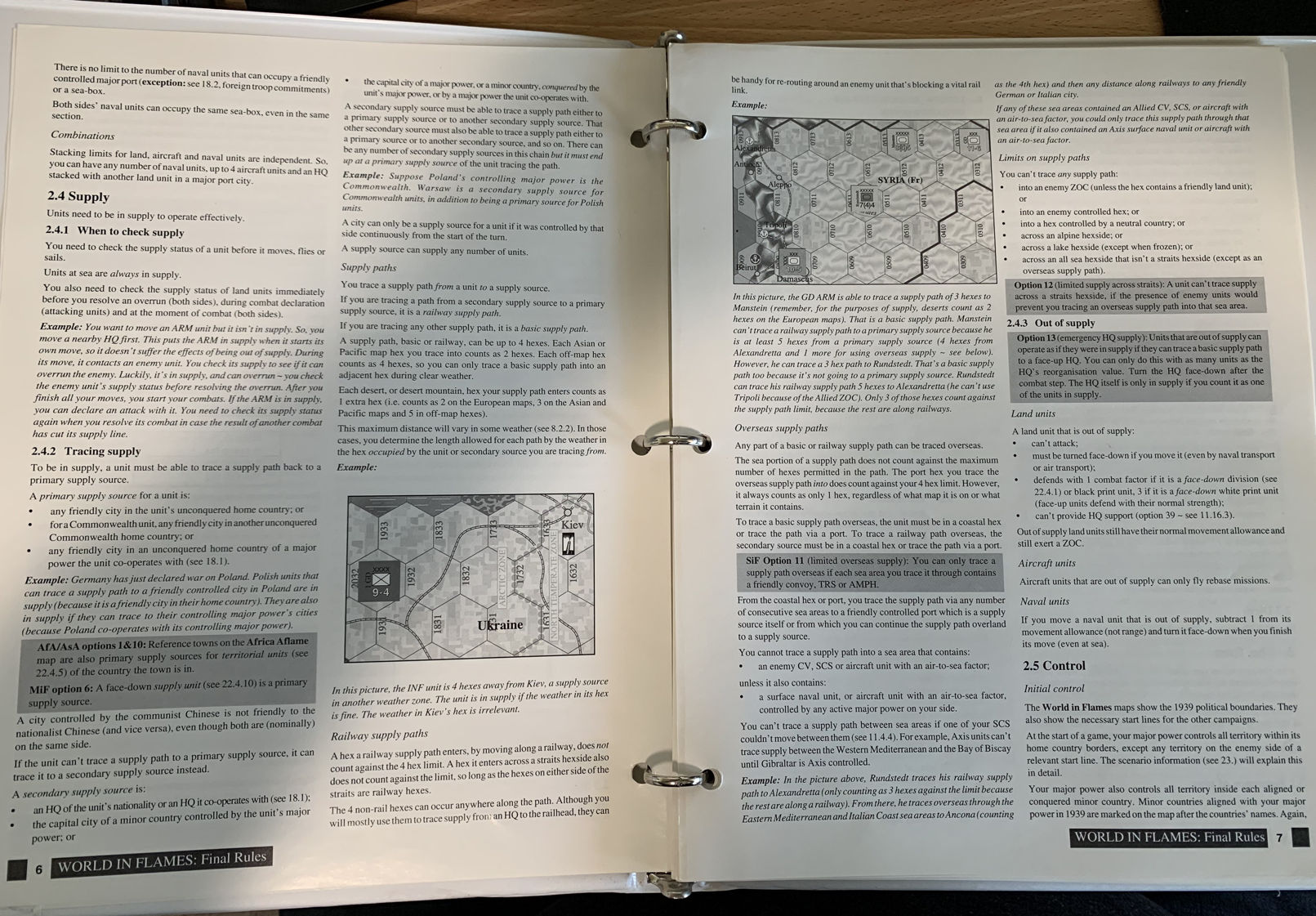

In a hex game, there’s no one there to stop them. While there are many beginner friendly, approachable hex games, there are also some very complex ones. This is a single two-page spread about supply lines in World in Flames.

This isn’t necessarily bad. It just is. And it is the source of my continually puzzled expression when people say things like “The rules for Horus Heresy are so complex…”. But it is definitely there, and is definitely daunting. There’s a reason World in Flames is on my shelf and hasn’t ever actually been played.

Fortunately, there are beginner friendly games. Compass Games has a whole section devoted to exactly that. And most wargames have, on the box, ratings for both Complexity and Solitaire Suitability. Meltwater is designated as an “Intro” game. NATO Air Commander is “Medium”. I think most miniatures wargamers can comfortably contend with a medium complexity game without much issue – and this is where almost all the games I own fall.

There is however a stylistic difference – many miniatures games are written as a sort of guide for learning, and teaching you how to play. This is partially driven by the idea that most people learn games by having someone tell them the rules, rather than reading the book.

This is why Games Workshop rulebooks are often fairly pleasant to read, and an actual nightmare to look things up in.

In contrast, most hex game rulebooks are intended as references – easy to look up things in, but not presented in a way that is as approachable from a learning standpoint. This is how you get things like Section J, Part 4, Subsection 6: Point Defense Firing Arcs. It takes some adjusting, and again it feels daunting, but stepping through it, and then playing your first turn somewhat carefully, presents a usually fairly straightforward path.

Where the Grog Games Are

So…if I’ve sold you on this, what now?

There are some places I’d point those interested in getting into hex games. I’ve mentioned one already, Noble Knight Games, which is a retailer with an extensive used game selection. It’s where I’ve picked up a number of games, and they often have decent clearance sales and the like where if I just want to try a game out, I can pick it up fairly cheaply. They also buy games, and give better rates for store credit, so if you’re looking to get rid of some old stuff…you could turn it into new-to-you old stuff.

Another major producer of games is GMT Games – they have well into the hundreds of titles. They have an interesting system, called P500, which is essentially a crowdfunding mechanism. A new game is offered up for a year, and they take heavily discounted pre-orders. When the game reaches 500 orders, it’s “Made the Cut” and heads into production. There’s often previews and the like, and you can cancel your orders. This has let GMT make a lot of fairly speculative games, and often means new games or reprints of old games can be had for a decent discount.

Compass Games is another well-known manufacturer, with both a curated list of good games to get started with, video tutorials about some of their games, and a semi-periodic magazine with a game, which is dangerously tempting. I’ve ordered a few of them – stay tuned.

Finally, because I’ve mentioned several of their games, Hollandspiele out of Detroit makes very cool, somewhat offbeat games. Want a solitaire game based around the Shackleton expedition? Supply lines in the American Revolution? Combat Search and Rescue in Vietnam? They’ve got you.

And where can you find discussions about these games? Reddit’s r/hexandcounter is decently active. And, it’s our intention, you’ll be finding more of these discussions here on Goonhammer.

Welcome to Hextoricals.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.