Welcome to the first design update for the Goonhammer Historicals project where we develop a skirmish miniatures game set during the Flower Wars, the pre-Columbian semi-ritualised warfare between the Aztec peoples.

Designing a new wargame is always a formidable task, and one of the hardest things is just getting it started – what I term “initial design”. This is because it’s at this very first stage where the broad sweeps of your concept come together, and any fundamental errors that creep in here can cause enormous problems later on.

But what do I mean when we talk about Initial Design? Well, it’s helpful for us to break the process of creating a game into several stages:

- Scoping and Research is where we work out what we want the game to be and then do the necessary research to ensure we’ve gotten that right and to try and understand the topic as best we can to ensure our design fits that brief. We’ll be covering some of the research on the place and period that the team looked at in future articles, and we touched upon the basic concept for the piece a little in our introductory article.

- Initial Design is where you take the research and concept and begin to marry the two together. You start making decisions on what the game will look like, some key concepts of how it will play, and work out if those things make sense together and if you can come up with the real guts of the game. It’s not essential at this point to actually have every single mechanic sketched out (in fact you shouldn’t) and we use a lot of “placeholders” – mechanical inputs/outputs that are simplified or entirely abstracted versions of the intended end result. The goal here is not to get a draft of the full game, but to produce a playtest alpha that has the broad strokes of the game and we can see if these basic concepts are working. The people who make these core decisions and create this initial design are Game Designers.

- Alpha Development then takes places with a lot of what we term “internal playtesting”. Internal playtesting just means testing that you’re not doing with a wider group – people connected to the project, or a select group beyond the development team, are playing it and feeding back. The goal here isn’t to polish each part or balance the factions or anything like that – it’s to answer the core question of: do these basic design choices fit the intended product, and is the basic framework fun. If it’s not then someone needs to fix it – this is the job of the game designer if it’s a fundamental change, but if it’s just a case of tweaking and altering things to get them back on track that’s done by Game Developers (who, in a small team like this one, are the same people as the designers).

- Secondary Design is what comes after you have that development done. At this stage the game still isn’t remotely complete but there’s some limited version of it that can be played and is fun and matches your theme and intent. Now is when the game designers step in and design the rest of the game – they fill in the gaps, flesh out the missing mechanics, put in the faction specific rules and unique elements and produce a playtest beta. This document might not include all the flavour text, fluff, full diagrams and worked examples, etc but it’s functionally a complete game – you can take it and play it and get the full experience of what the game will be.

- Beta Development is what happens at this point. Internal playtesting continues, but also you usually try and open it up to wider testing. You stop hand-holding and guiding your testers so much and throw it out to them to devour in its raw state and you encourage them to try as many configurations as possible. There’s a whole art to running good playtesting (which we won’t get into here) and generally the more the better. During this process the Game Developers really step up as the primary actors – they tweak, balance, rework and edit the game until it is polished and working as it should.

- Rulebook Writing is one of the last steps. A Rules Writer (again might be the same people, certainly will be here) takes the playtest beta after all the development that’s happened and writes it up into the actual text that will be in an actual rulebook. They write that flavour text and further explanation, make sure that diagrams are created, and so on. This is half editing, half writing and always a complex task. Often this happens simultaneously with beta development, because you really want the later stages of that development to revolve around unguided testing, where you throw a rulebook at players and let them get on with it and see what happens. What you end up with is a manuscript, which can be handed off to an editor and layout artist for publishing.

At this point you then head into layout and graphical design and all the other aspects that are more to do with publishing than with game design and development, so we’ll ignore those steps. Not every games studio follows this process exactly. Many have more (or fewer) iterations of development and design. Some skip over whole sections – but it’s a good rule of thumb, and it’s roughly how we’ll be working for The Flower Wars.

Getting Started

So here’s the design brief that we agreed up initially:

To create a historical skirmish game (with roughly 4-12 controlled units per player) that allows, on a small play surface, games that evoke and recreate the Flower Wars, ritual wars of the Aztec Empire that focused on personal glory, the capture of prisoners and feats of martial prowess.

Mechanical unit here doesn’t mean “group of models” necessarily, but rather any individual “piece” that mechanically operates as a single thing. So we could be looking at anything from 4-12 individual models all the way up to 4-12 large warbands – it’s keeping it intentionally vague at this point.

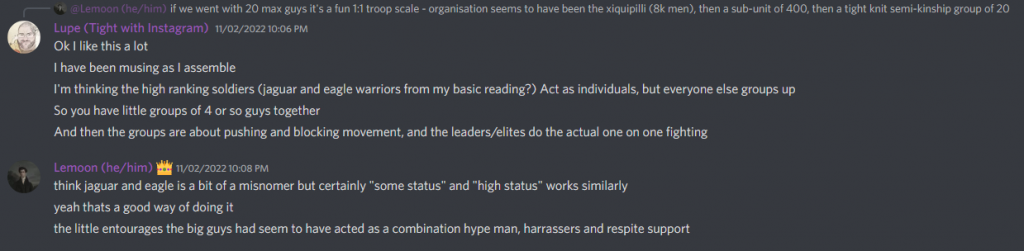

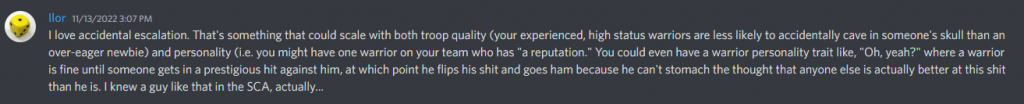

We started with a sound reading of the historical facts that, as ever, sent us down a rabbit hole it would take days of discussion to escape:

![]()

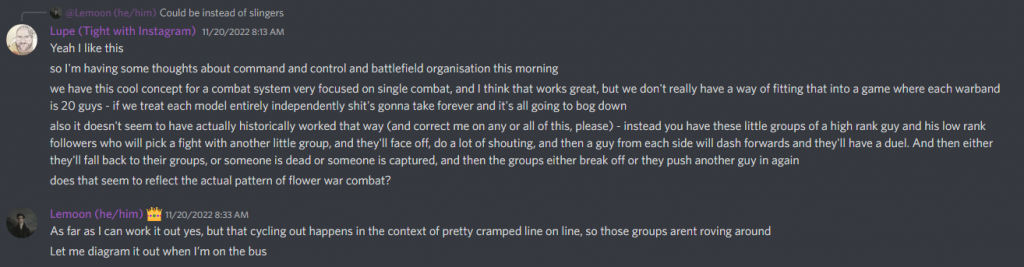

This immediately inspired the group, and we started sketching out how we’d create the game based around this number. This led to conversations about how those troops were arranged:

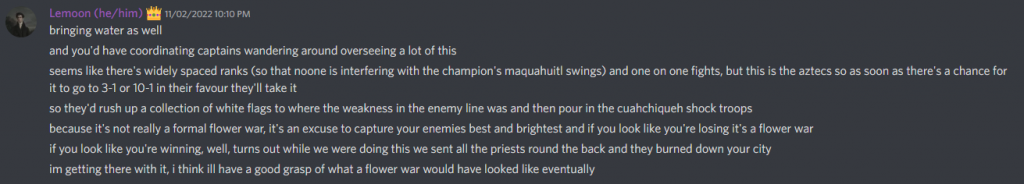

Before we ended up with some sense of what a flower war in particular was:

[Lenoon: I was wrong about some of this]

Even if there were some hiccups with the less academic of us:

But this actually left us in a good place, we had the dynamic nailed down:

You have your champions who fight alone and who end up pairing off in one-on-one fights. Activation-wise once they’re engaged together activating one will immediately snap off an activation of the other, so these fights can be nice and tense and a back and fourth without lumbering us with a reaction system that seems unnecessary on top of alternating activations. Then we have our little groups of common fighters, who mostly fight with spears and slings and bows, and who are activated in their little units. They generally harass and block and screen, but if there’s an opening you just have them shoot the hell out of their opposite numbers. Tie this together with a deception/escalation system where everything starts nice and formal and ritual and you can choose to escalate it at opportune times to make everything more “real”. Obviously you are trying to pick the best time to do that. And maybe that last bit is what lets you “upgrade” your little groups from “I’m bringing the guy water” to “blocking enemy units” to “shoot you with arrows”.

There was a key tweak to the escalation concept though that needed incorporating:

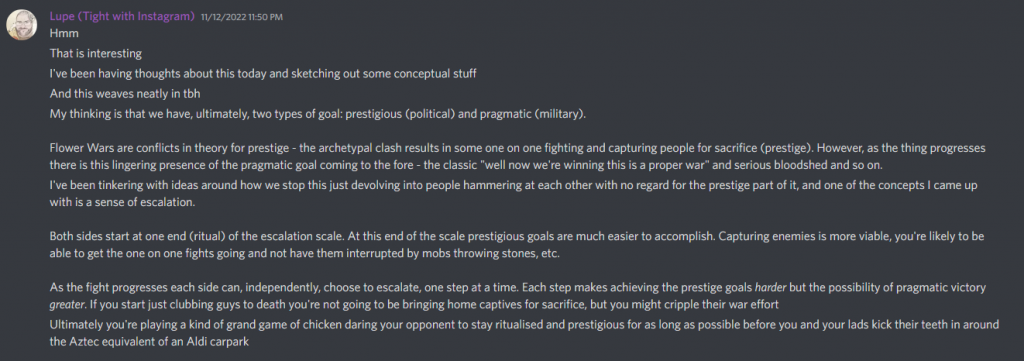

What we were trying to hit next with the “vibes”. How we wanted the game to feel. This whole discussion went back and forth a lot but we ended up here:

Contact with the Enemy

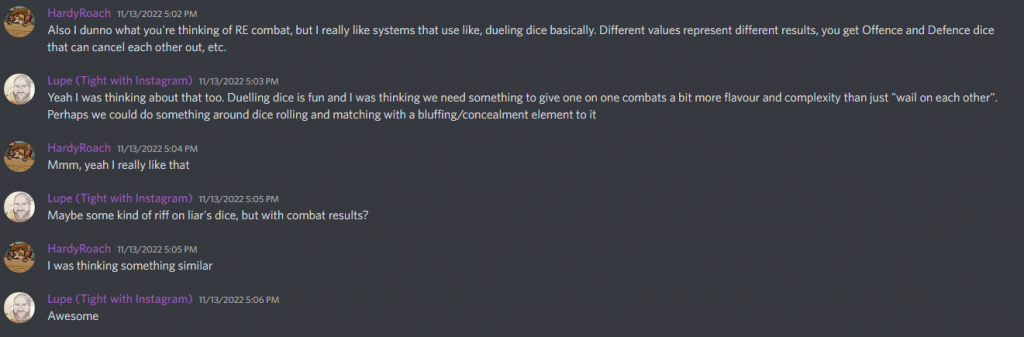

Obviously this was early days and we were soon to encounter some problems. We started having some discussions about actual mechanics, and top of our list was some kind of combat mechanic. To begin with things went well:

Before we were immediately distracted by researching traditional Aztec games, that mostly seem to have involved beans with holes in them:

We knew that the duelling, the one on one fights that could result in captures, were absolutely essential, but building a system that only did that would cause problems if we ever wanted the groups to actually fight too. Building a mechanical system that supported quick 1v1 duels and group clashes began to present some problems:

This provoked a flurry of ideas: breaking the overall numbers into ritualised groups, having the groups be more formal “single models” formed of multiple models on a single base, a bunch of weird discussions about beans, at least one discussion about the definition of a miniatures wargame, and then a lot of talk on how to reduce spiralling complexity of tracking twenty guys at once before a moment of sanity:

Turns out the original design brief probably should have been something we stuck to – the alpha playtest draft has 4-10ish guys on each side.

Got Your Back

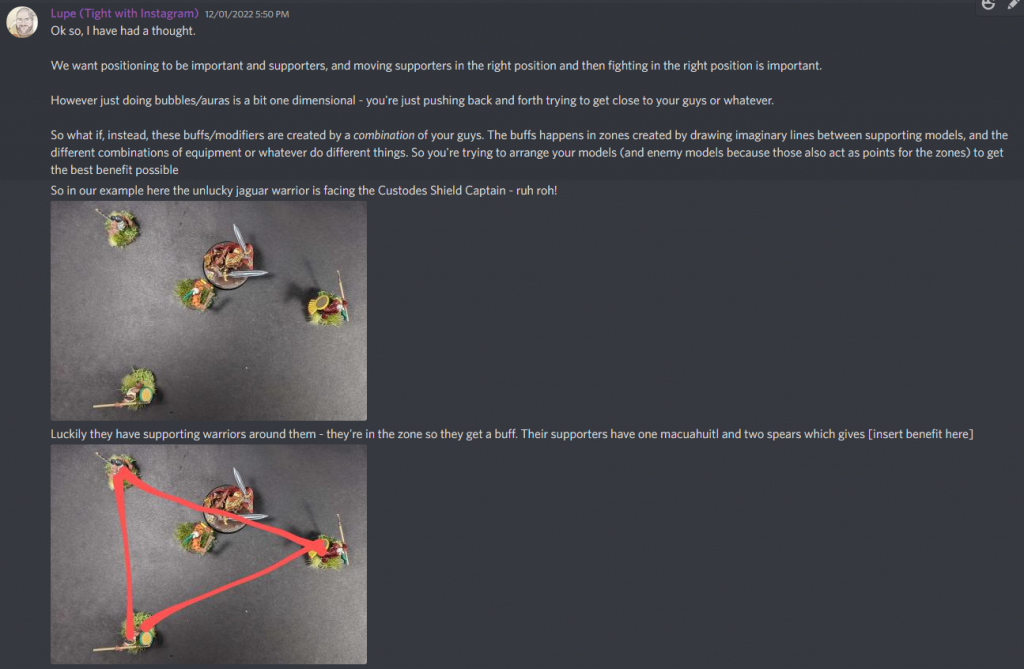

One thing we really needed to nail down was that sense of a bunch of warriors supporting a champion in a duel. We talked about a lot of different options (hexes, auras, etc) and then I woke up one day from a nap with a headache and some Thoughts:

This seemed to solve the problem though one of the team had a very prescient comment:

I would stubbornly hold out for multiple polygons for days until testing showed it was an absolutely insane idea and we settled on one.

The Alpha Playtest

From all our discussions (and there are far far more than I could possibly show here, days and days of talk about the direction of the game) an Alpha Playtest document was compiled. We all did bits of design, filling out a mechanic in draft and then it being talked over and revised.

What we’ve ended up with is something playable – you can get it to table and you can throw dice and move models around and someone will win. And that’s basically where the Initial Design phase ends – from here we move into Alpha Development, and that’s always where things get exciting. We’ll talk about that in the next design update.

If you’re a Patron you can sign up to playtest the alpha! If you have any thoughts, ideas, comments or criticisms leave them below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.