Last year’s stacked lineup of games for the Game Awards had us thinking: What was the best year in gaming? As part of our series on determining gaming’s best year, we’re putting together an article on each year, charting the major releases and developments of the year, and talking about both their impact and what made them great.

The Year: 1990

1990 marks the true beginning of the 16-bit era for video game consoles, with the Super Famicom releasing in Japan in November and in the United States one year later. Nintendo execs had been in no rush to build new hardware, but as the PC-Engine and Mega Drive began to erode their market share, they changed their tune. The Super Famicom, or Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) in the United States, was by far the most graphically-powerful of the three 16-bit home consoles, boasting the ability to display up to 256 colors simultaneously from a palette of 32,768 and a set of eight graphics modes for manipulating and displaying background layers. The most famous of these is Mode 7, which was used to distort and scale flat images to create the illusion of 3D effects. The Superfamicom launched with two titles, Super Mario World and F-Zero, and added Actraiser, Final Fight, Gradius III, Pilotwings, Populous, Ka-Blooey, and SD The Great Battle one month later.

On the PC front, Microsoft released its Windows 3.0 operating system in May 1990. The OS featured an overhauled graphical interface and Microsoft had put a ton of work into making the software more appealing to the general public. Part of that was building games into the OS, and Windows 3 shipped with Tetris, Solitaire, and Minesweeper. Windows 3 would be a solid program for games, seeing a large number of releases before the release of Windows 95. It’s during this period that games largely moved from Apple computers to PCs, for a variety of reasons.

In 1990, Peter Adkinson founded Wizards of the Coast, a company dedicated to publishing role-playing games. They’d go on to shift their focus to card games a few years later, however. Also founded in 1990 was wargame company GMT games, which would go on to publish the COIN series of games and Twilight Struggle.

SNK Launches the Neo Geo

In 1990 developer Takashi Nishiyama (the creator of Street Fighter) was working at Japanese arcade developer SNK Corporation on a new hardware project and asked the question: “What if we built arcade hardware which could run on swappable ROM cartridges like a console?” From there, SNK released both the Neo Geo 4-slot arcade cabinet (which held four swappable cartridges), and its Neo Geo home console, which hit shelves that same year. Unlike other consoles of the time the Neo Geo was considerably more powerful graphically and marketed as a 24-bit console. Compared to other machines, the arcade cabinet was pretty cheap, allowing arcade operators to add or swap out games as needed, making it a commercial success. In comparison, the console was not cheap, retailing in the US for a whopping $649.99 ($1,581 in 2024) for its two-controller version with a pack-in game and $399 for its no-frills version. That’s insane, and would largely ensure that the console was more an interesting footnote than a real contender, particularly since its library would end up being mostly fighting games.

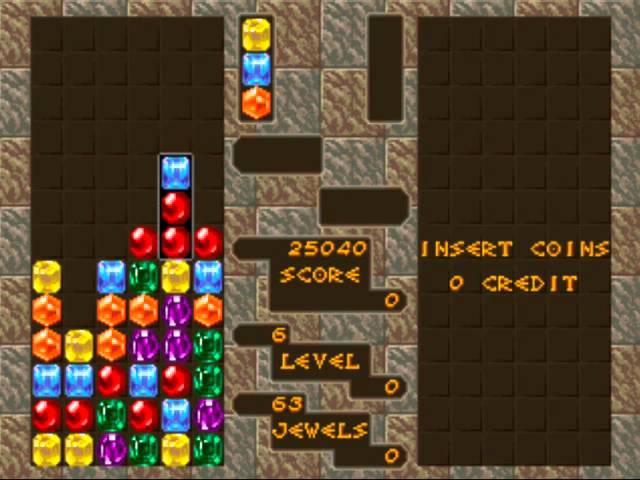

Columns

From the release of the Famicom/NES, Nintendo held an iron grip on the industry through its licensing agreement. You couldn’t make games for Nintendo platforms without a license, and you wouldn’t be granted a third-party license without agreeing to Nintendo’s policies. Some of these were quality-related, as a way to avoid saturating the market with mediocre games, but others were just focused on killing competition. Specifically, Nintendo’s third-party licensees could not bring the same game to competing consoles. This meant that if a game released on the NES or SNES, it wouldn’t be coming to the Genesis or Turbografx-16. So what do you do if you’re Sega and you want to add a puzzle game like Tetris to your library? Build your own. Or, in the case of Columns, buy the rights to the game from its creator, Jay Geertsen.

Enter Columns, which Sega released to arcades in March 1990. Columns is a tile-matching game where players drop columns of 3 gemstones of varying colors. Matching three or more gemstones of the same color in a row or column (diagonally counts as well) will cause them to disappear, leaving gems above to fall into the open gaps. Players compete to score high points as columns drop faster on higher levels. It’s a wonderfully addicting puzzle game and one that’s easy to understand, with solid two-player head-to-head play.

Dr. Mario

On the other side of the console war was Nintendo’s own entry into the puzzle game space, Dr. Mario. Another tile-matching game, Dr. Mario confronts players with a jarful of colored viruses, and players must match colored pills to those viruses in groups of three or more to eliminate them, clearing the jar to advance to the next level. Dr. Mario had a banger soundtrack and was a hit on the US and Game Boy.

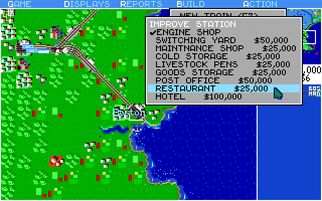

Railroad Tycoon

In 1990 MicroProse released Sid Meier’s Railroad Tycoon, a business sim in which players build and manage their own railroad company. Players build stations and track, schedule trains, and handle the day-to-day operations of the company as they attempt to build an empire.

Cyberpunk 2020 and GURPS Cyberpunk

Although the movement started to pick up steam after the publication of William Gibson’s Neuromancer in 1984, tabletop and video games were really starting to latch on to the cyberpunk aesthetic in 1990, feeding on fresh imagery from 1988’s Akira, released in December, 1989 in the west. 1990 would see two major attempts to bring cyberpunk worlds to the tabletop, Cyberpunk 2020 and GURPS Cyberpunk. Cyberpunk 2020 was the second edition of the game, replacing 1988’s Cyberpunk 2013, and would create the specific universe that would go on to house CD Projekt Red’s 2077 and Cyberpunk: Edgerunners. That same year Steve Jackson Games released their own sourcebook for cyberpunk games through the GURPS system. Both games featured lengthy rules for netrunning and attacking computer systems.

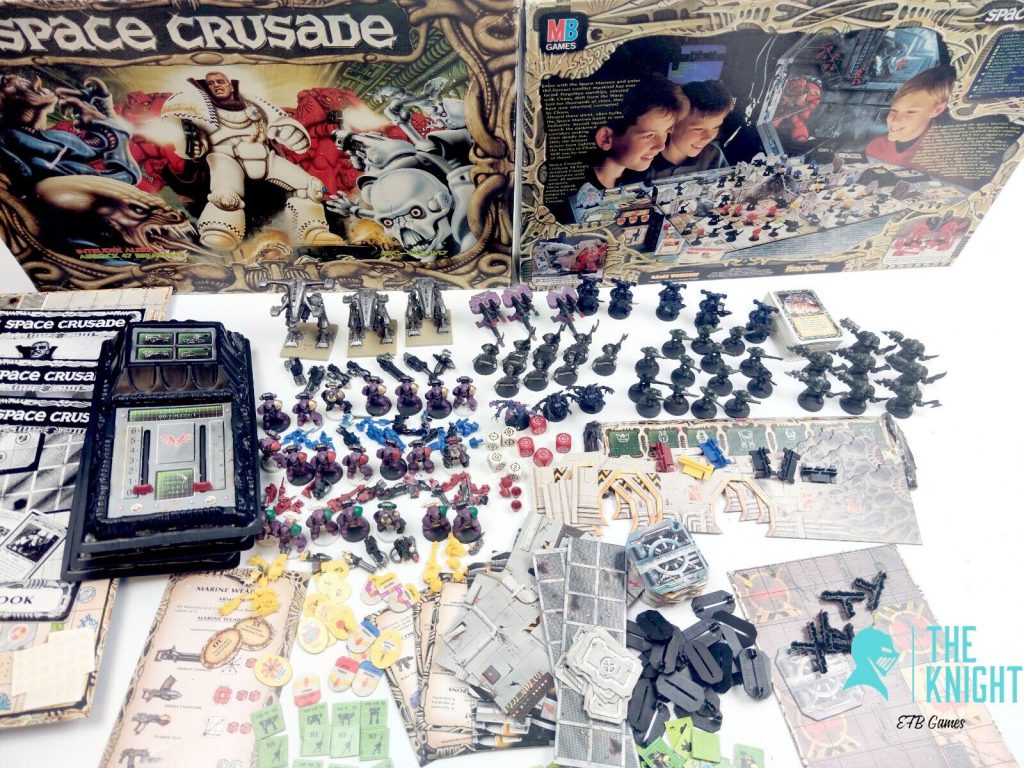

Space Crusade

Somewhere between Rogue Trader and Warhammer 40,000’s second edition was Space Crusade, a 2-to-4 player game released in 1990 and published by Milton Bradley. The game pits teams of space marines against Chaos, Orks, Genestealers, and a set of aliens who look remarkably like Necrons, all controlled by a GM-like player. The whole thing plays like a sort of HeroQuest in space set against the backdrop of the 40k universe, but it’s a much more competitive game than story-driven. Space Crusade isn’t the best game but it’s an interesting stepping stone for Warhammer 40k.

Super Mario World

The fourth (or fifth) mainline game in the Super Mario Bros. series, Super Mario World debuted with the launch of the Super Famicom in 1990 and introduced the world to Mario’s biggest adventure yet, with a large, more open world, branching paths and exits, and all new power-ups. In many ways it’s a superior game to its predecessor, though there’s a bit of a trade-off in simplicity and accessibility. Still, if you were to argue that this is the best Mario game, you’d have many supporters.

F-Zero

The other big launch title for the Super Famicom, F-Zero is a futuristic racing game which really acted as a showcase of the console’s Mode 7 graphics to place a 2D sprite on a shifting, futuristic race track. The game’s tight controls and colorful, imaginative tracks made it a stand-out title for the console despite its punishing difficulty.

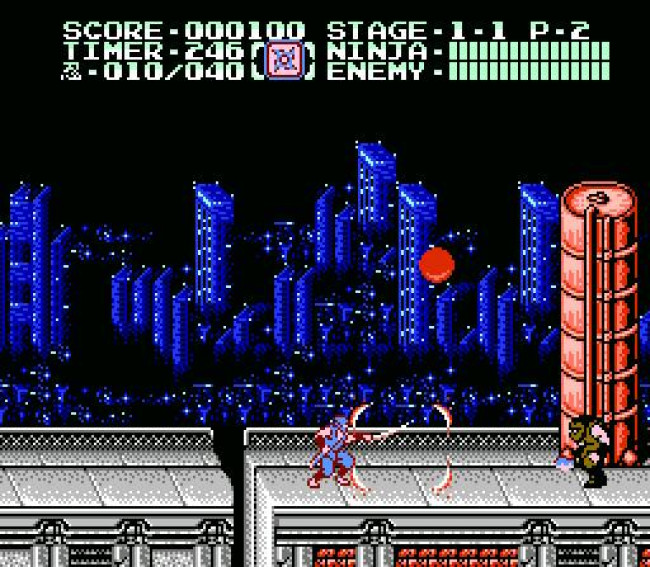

Ninja Gaiden II: The Dark Sword of Chaos

Tecmo wowed players with its home console port of Ninja Gaiden three years earlier, overhauling the game with cinematic cutscenes, a twisting narrative, and an emphasis on platforming. They’d perfect that formula with the console follow up in 1990, once again following Ryu Hyabusa as he deals with a new threat one year after his defeat of Jaquio and the demon. Ninja Gaiden II does everything the first game did but better, with better graphics and sound and much sharper gameplay. It’s a great example of how console developers were hitting their stride with the NES well after the release of 16-bit competitors.

Aliens

Konami had already done a pretty solid job ripping off the imagery in the Aliens movies with its Contra franchise, first released in 1997, but they’d get the chance to do the real thing with their 1990 arcade release of Aliens. The game offers two-player co-op gameplay and has players taking on the role of marines fighting their way through LV-426 in a variety of levels which loosely model the movie’s progression. Aliens was incredibly good fun and is one of the best arcade games to never receive a home console port.

Smash TV

In 1990 Williams released this twin-stick shooter in 1990 to limited critical acclaim and moderate commercial success but in the decades following have been very kind to the game. Smash TV has players take on the role of contestants on a dystopian game show, trying to survive an onslaught of bullet hell-style obstacles while collecting power-ups and cash. It’s a hectic game which paved the way for games like Monday Night Combat, Enter the Gungeon, and Helldivers years later.

Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake

Hideo Kojima’s fourth game and the sequel to 1987’s Metal Gear on the Japanese MSX2 PC platform, Metal Gear 2 is notable for a few reasons, one of which being that it never received a western release and was developed as a response to Konami’s Snake’s Revenge for the NES. Snake’s Revenge was developed by Konami to be the sequel to Metal Gear, but when Kojima learned about the game he requested (and was granted) permission to make his own sequel. Metal Gear 2 follows a top-down formula much more similar to the original game while giving players a much larger set of moves and tricks to evade enemies. The game also goes much, much heavier on the plot, leading to a showdown with Gray Fox and setting up the series for a triumphant return nearly a decade later. Metal Gear 2 is a bit of a lost relic in the west but was a big hit on the MSX on release and is an underrated gem.

Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest close out their time on the Famicom

Both Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest received sequels in 1990 – Final Fantasy III and Dragon Quest IV, respectively, and both represented the franchises’ final entries on the original Famicom. Behind the scenes work had already started behind the scenes on the series’ next chapters for the Super Famicom but only Dragon Quest IV would see an English translation and western release. Both games are interesting in their own right, each taking things in a new direction for their respective franchises – FFIII with the introduction of a job system and DQIV with a chapter-based storytelling approach and a larger cast of changing party members.

LucasArts Redefines the Adventure Game Genre

Although LucasArts, the game development studio of LucasFilm, was no stranger to adventure games, having created Maniac Mansion and several other notable titles, they’d completely redefine the genre in 1990 with the release of two games; Loom and The Secret of Monkey Island, establishing themselves as the genre’s foremost pioneers. Of these, The Secret of Monkey Island was a much more traditional point-and-click adventure game, following the adventures of Guybrush Threepwood as he solves puzzles in service of thwarting the ghost pirate, LeChuck. The game was particularly notable for its sense of humor and tight writing and would spawn a series of beloved sequels.

Loom on the other hand was a much more serious game, telling a fantasy story while centering gameplay on musical notes and sequences which can be played, combined, or reversed to create specific effects and interactions. Players explore the game’s island solving puzzles with the notes they have (you get more over the course of the game), fulfilling various prophecies and potentially saving your people. It’s in the same genre as Monkey Island but a very different game in terms of tone and mechanics, and a great example of how varied the genre could be.

Hoity Toity

Willie H: In Hoity Toity, you vie for the best collection of valuables acquired through legal or illegal means. You can either pay for valuables or steal them with thieves. As you grow your collection you’ll start to “exhibit” them, granting you movement around the board. This is important, as the winner is whoever is farthest around the board and near the dinner table near the end of the track. So, tending to your collections and exhibiting them at just the right times will gradually progress you towards the end.

Despite the odd fractions, Hoity Toity is a whimsical set collection game with the right amount of auction and take-that gameplay that made every choice, no matter how small, very intrinsically important overall. It stood out to me six years ago, and it still stands out in my memory today.

Why It Was the Best Year in Gaming

1990 isn’t the strongest year for the 16-bit home console generation, but it was a solid year for tabletop games, and a fantastic year for PC gaming. Adventure games in particular were thriving, and not just the LucasArts games – in addition to Monkey Island and Loom, King’s Quest V, Rise of the Dragon, and Quest for Glory II: Trial by Fire gave us a full slate of games to explore. On the tabletop we saw the rise of the Cyberpunk genre with Cyberpunk 2020 and GURPS Cyberpunk, the former of which would define the genre for decades to come.

Just because the 16-bit generation wasn’t firing on all cylinders doesn’t mean that home console gamers didn’t eat well in 1990, either: the 8-bit NES received some of its best titles that year, from the likes of Dr. Mario to Mega Man III, Ninja Gaiden II, Final Fantasy III, Dragon QUest IV, StarTropics, Little Nemo, Snake’s Revenge, and my personal favorite, SNK’s action RPG Crystalis. Meanwhile the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis was building a sizeable lead over its Super Famicom rival, with standout titles like Michael Jackson’s Moonraker, Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom, Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse, and the home port of Columns.

Finally, 1990 was a massive year for arcades, featuring both a number of classics which would stand the test of time – Aliens, Merc, Smash T.V., Columns – and some more controversial picks which nonetheless made a big splash and changed the future of arcade games. Specifically, Pit Fighter and American Laser Games’ series, including Mad Dog McCree, which reintroduced FMV games and digitized sprites to arcades.

So while 1990 is shorter perhaps on All-time greats – though Super Mario World definitely belongs in that list – the year saw a massive breadth of titles and quality releases across genres and formats.

This article is part of a larger series on the best year in gaming. For more years, click this link. Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.