Welcome to the third installment of Goonhammer’s ongoing chronicle of the history of the Black Library (40K Edition). Today we’ll be looking at the close of the Watsonian Years, including his conclusion to the apocryphal Inquisition War trilogy. By the end Games Workshop would have its first 40K novels, and we would have four of the wildest things ever written for the property.

Our Story So Far

Games Workshop’s foray into Warhammer 40,000 fiction began in 1990. By then they’d watched other games like TSR’s Dungeons and Dragons and FASA’s Battletech spawn tie-in novels in an effort to expand the market for their creative worlds.

CEO and co-creator Bryan Ansell had a high ambition. He didn’t want to just settle for pulp fiction, but rather wanted “real books by real authors set in his beloved Warhammer domains.”1

To do this, Ansell leaned on series editor David Pringle, who had joined the company in 1988. Pringle was particularly well-positioned for the task, being the publisher of the fantasy and science fiction magazine Interzone.

According to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Interzone- whose first issue was published in 1982- was behind the reinvigoration of British sci-fi after “long years of near-stagnation…catalyzing a second new wave of UK science fiction.”2 Amongst its many recognitions Interzone would eventually secure both Hugo and Nebula Awards.

As a result, Games Workshop wasn’t coming to the task cold. Ansell had Pringle source talent from his network of writers, and Pringle delivered.

The Mid-90s

By 1997, everything we’d seen so far for Games Workshop’s foray into speculative fiction would change. Gone would be the startup model of hiring established voices to put their spin on the Warhammer universe, and in its place a more deliberate effort to develop and cultivate talent that could channel GW’s developing vision of what they wanted their properties to look like.

But the mid-90s, those still belonged to Ian Watson.

When asked how he ended up writing for the sci-fi side of things, Watson noted that when Pringle had put out the call for writers, “all the buggers chose to write a normal medieval fantasy and just put in Warhammer names. So when I came to realize I was going to have to bite the bullet… there was only 40K left.”1 A slightly uncharitable take, perhaps, but certainly Pringle had no shortage of writers for fantasy stories as Games Workshop released two full anthologies of shorts in the Autumn of 1989 (Ignorant Armies and Wolf Riders) alongside the novel Drachenfels.

Watson had no particular attachment to the Warhammer properties, but was certainly keen for a paycheck. Games Workshop’s offer of £40,000 for services rendered was too good to pass up.3 Very quickly, however, something in Watson changed as the mercenary wordsmith element took a back seat.

“As soon as I started,” he noted, “I became thoroughly involved and had wonderful hectic fun going over the top in bizarre lurid Gothic madness. Writing should be fun. Writing should disorder and then re-organize readers’ minds so that they see the world in a different way.”3

“I did have such fun writing those books. You can go completely over the top in gothic lunacy.” – Ian Watson3

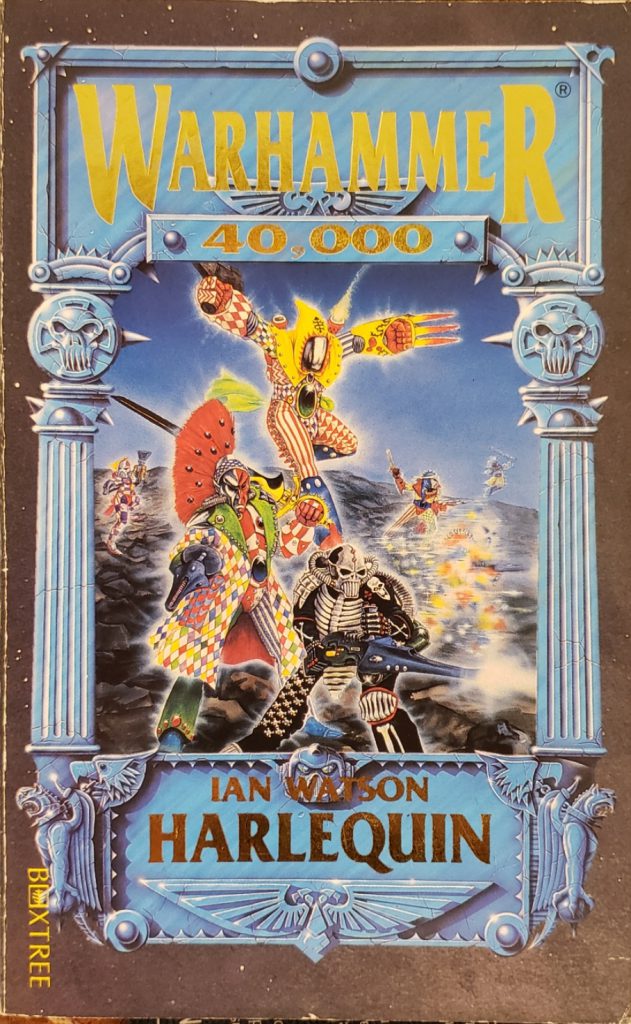

Harlequin, 1994

The successor to 1990’s Inquisitor, Harlequin was not only published four years later but also set a century after the events of the inaugural book. Inquisitor (now turned renegade) Jaq Draco and his retinue are continuing to contend with a conspiracy within the very Inquisition itself, one involving a psychic Armageddon weapon which may lead all the way up to the Emperor.

A mysterious group of Harlequin are mustering to hold a Ceremony of Cataclysm, while the Inquisition alongside Space Marines move to stop them (and plunder their arcane secrets). Draco and the gang are thrust in the middle, as they race to unravel a mystery that takes them through the webways and all the way to the Black Library itself.

In addition to the wild plotting, the writing too is unmistakably Wilsonian. We examined some of his more lurid prose in our last installment, and Harlequin does not disappoint:

Meh’lindi dropped her Sirian silks to the obsidian floor. By the light of the glowglobe Jaq saw how her tattoos of snake and beetles and spider had faded. Those seemed to be mere mottlings of sublimely muscled skin, dapplings as though she stood naked in a leafy grove shafted by golden sunlight.

Soon, the heart under the neat high breasts pressing against him beat quickly. Her lips breathed into his ear, “My heart must beat faster to be an Eldar heart.”

Soon, due to their ecstatic exertions – sinuous on her part, blunter on his – it did beat more swiftly.

“I consecrate you,” Jaq gasped when his chrism streamed within her unguent.

Who says romance is dead?

In a development that will certainly be familiar to Black Library readers of today, Harlequin was also released by the publisher (BoxTree) in a collector’s edition, a large hardback book priced at £14.99. (For reference, according to our friends at the Bank of England that would be the equivalent of £30.23 today, but truly a bargain at any price!)

As Watson recounts, BoxTree sent 200 copies of the edition to Game Day in Birmingham4, where he would be doing a book signing. Every copy was gone within two hours. But his success was not met with the hoped-for enthusiasm as he soon learned that Games Workshop had opted against carrying them in their retail outlets giving the rationale that the book was “too big for their shelves.”5

“I soon realized that the book was perceived as competing with cardboard boxes containing some bits of plastic… for which there was a much higher profit margin.”5

A victim of his own success, perhaps. All the same, Watson was on the hook for one more book to round out the trilogy and it dutifully arrived the following year.

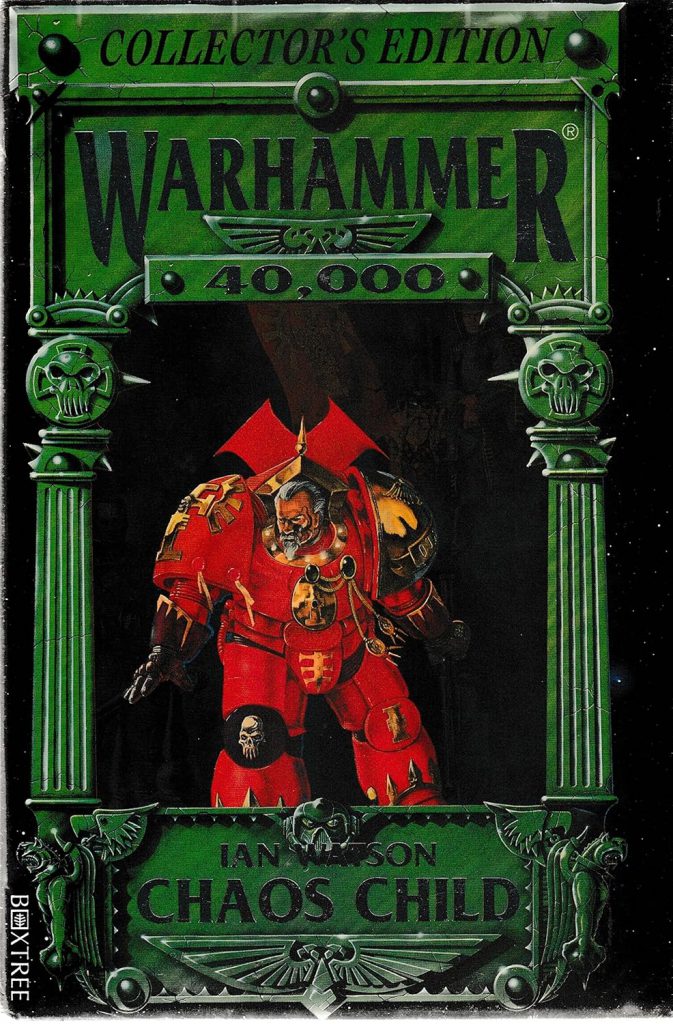

Chaos Child, 1995

In a number of ways, Chaos Child signified the end of an era for Games Workshop. David Pringle had already exited the company in 1991, and the Inquisition War was the last of the early trilogies to conclude. Kim Newman’s run on the vampire Genevieve Dieudonné wrapped up in ’93 with Genevieve Undead, while David Ferring’s Konrad Saga saw it sunset that same year with Warblade.

In fact, we wouldn’t see another new Warhammer novel hit the bookstore shelves until 1999. Until then, hungry readers had to content themselves with the final act in Inquisitor Jaq Draco’s sordid tales of derring-do.

Ultimately Chaos Child turns out to be far more Empire Strikes Back than Return of the Jedi. Plans go awry, misfortune abounds, and the whole thing ends on a rather somber note. The story centers on Draco’s efforts to resurrect his assassin companion Meh’Lindi, who had been killed in the webway by a Phoenix Lord in Harlequin. Consumed with grief, Draco trespasses well into heretical territory in pursuit of the forbidden knowledge as he spirals into obsession. It was a bleak coda to the series, one which Watson himself has said he had half a mind to remedy.

“I did have a further Inquisition War novel in mind,” he noted, “because by the end of Chaos Child one of my characters was insane, another was hopelessly lost, and a third was dead, and I had come to care for the characters, so I thought I should get them out of these particular scrapes, even though in the world of 40K there aren’t exactly going to be happy endings in the usual sense.”3

Assessing Watson

While foundational to the Black Library, Watson’s body of work hasn’t aged well and, when remembered at all, is mostly invoked for the more salacious bits. That’s not entirely unfair; Watson was given an opportunity and he chose to populate it with imagery like phallic boarding tubes penetrating Tyrranid sphincters, poop marbles, and tentacle violation.

By the same token, Games Workshop could not have been entirely in the dark about what it was getting. This was, after all, the author who had published a book titled Orgasmachine in 1976. By the time he was recruited for Warhammer he was a well-established author in his own right, with his own style and own voice.

But if we’re inclined to fairness, we should remember too that this was largely uncharted territory. Today’s aspiring Black Library author has an endless amount of material within which to marinade their imagination. Watson’s point of entry was a stack of gamebooks and issues of White Dwarf.

“When I wrote the four Warhammer books,” he noted, “the biggest problem was converting mentally from a Citadel miniature and board game with rules and background studies, and characters almost like human machines, and trying to give them some kind of human feelings, emotions, background and motivations, which nobody had managed before.”3

Today, Watson remains stubbornly unapologetic about his work for the Black Library.

“The audience at the time for these first novels were Goths who were 20 years old, 21 years old, with rings through their noses and tattoos on their breasts. You know I also imagine that they engaged in some sexual capers as well, so this is really normality.

“But it’s controlled in my book. Fox example, Jac Draco only makes sacred love once, with the female assassin Meh’Lindi. I mean, you know that it’s rather like in ancient Babylon, when it was the legal duty of every young woman to go and sit in the Temple of Ishtar. It is worth exploring. On the many, many worlds of the Imperium there are bound to be all sorts of different social customs. And heresies!”1

Next Time…

With the Watsonian pre-history now in the rearview, 1997 is the seminal year where the Black Library as we know it today begins to take form. And it’s all because of a little magazine of short stories called Inferno! See you then!

Footnotes

- As Watson himself put it in an interview at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=msoXVz-bJZo

- Source: SFE: Interzone

- So he says: A Bundle of Interviews – Ian Watson

- Not in Alabama

- Source: BACK TO THE FUTURE: SPACE MARINE! – Ian Watson

- It’s quite a tale, as Watson relates on his site at Orgasmachine – Ian Watson

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.