The Noir genre has not been mainstream for a long time, but it has also never been fully absent. Whether it’s the neo-noir Nightmare Alley or the neon-noir Bladerunner 2049, the genre has never been far from our screens. With the recent publication of two RPGs, Osprey Games is working to ensure it’s not far from our tables either.

Crescendo of Violence is the neon-noir take. The setting neon-glitz and post-cyberpunk tech paired up with rapid hyperviolent combat. Think Cyberpunk (or Android: Netrunner!) meets John Wick. Meanwhile Hard City is set in the black and white undercity beloved by Humphrey Bogart and Orson Welles. Think smoke-filled speakeasies and dames with loose lips and looser morals.

Both games riff on noir themes, but they differ in more than just setting. The publication and release of these two games so close together offered me a fun opportunity to compare two takes on similar stories.

Crescendo of Violence

Don’t Call it Cyberpunk

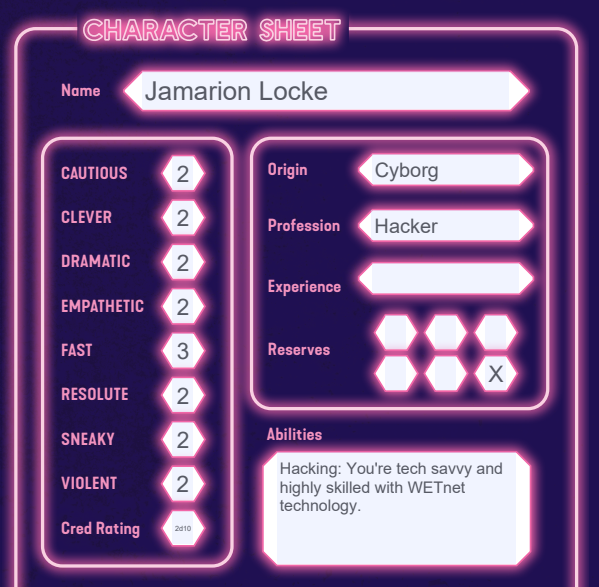

Written by Alan Bahr, Crescendo of Violence explicitly sets out to marry two of Bahr’s favorite genres: neon-noir and heroic bloodshed. Neon-noir is a modern or futuristic take on classic noir stories. Heroes are morally grey, officials are corrupt, violence is rampant, and protagonists tend to be broken down and isolated from the world around them. That’s the noir.

The neon comes in from the world around them and is similar (thought distinct) from cyberpunk. Bahr’s world features the powerful global corporations, body modification tech, and hacking you’d expect from cyberpunk but decidedly turns the conflicts inward. Cyberpunk stories are about fighting the man, Crescendo of Violence is about fighting your demons. In fact, Bahr makes a point of describing the world of Neo York as post-cyberpunk. The corporations rose, and have fallen into a more manageable state.

The world of Crescendo is rich. Advances in energy tech have almost eliminated scarcity, though concerns about AI control and class stratification abound. Citystates have emerged and drift tech means that entire cities can break off from their landmass and float over to join these amalgamations. Amidst it all, crime and corruption never changed.

Active Action

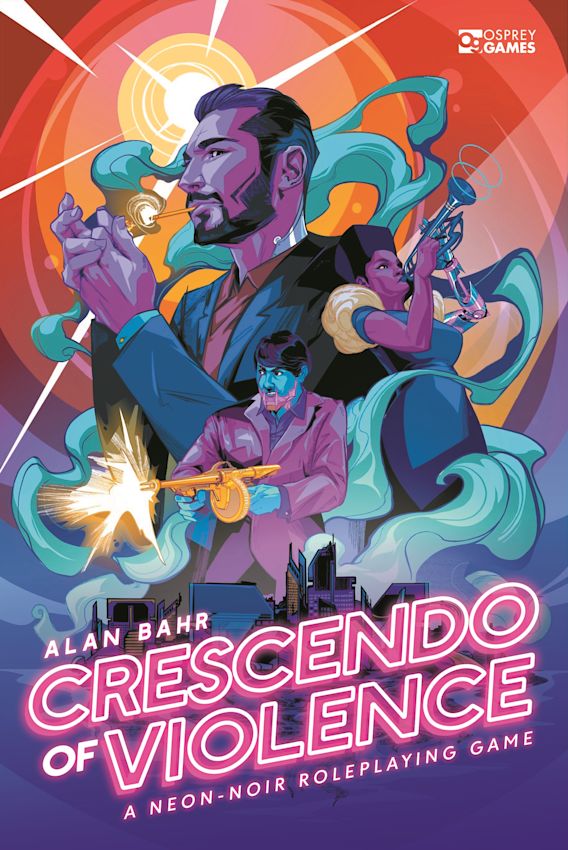

In order to support the heroic bloodshed side of this mashup, Crescendo of Violence sports a rules system that is more robust than I initially expected from this slim volume. There are 8 stats (called Paths) that represent how a character goes about something. The VIOLENT path is commonly used in combat but the EMPATHETIC and RESOLUTE and others ensure that there are multiple, ahem, paths for your character.

Each path has a rating representing how many d10s are rolled when taking a test. The DM will set a target number between 1 and 10, you’ll grab your pool along with any modifiers, and send the dice spinning hoping to meet that number on at least one die.

Where things get interesting is the combination of Action Tokens and Momentum. Each player has three Action Tokens—green, yellow, and red. One must be spent with every roll and each will give you advantage, nothing, or disadvantage respectively. Unfortunately for the player, all three must be spent before they are refreshed. While this is a bit heavy handed, the red tokens ensure that the downtrodden nature of the noir genre are always at the surface.

Momentum is gained any time a natural 10 is rolled on any die, and can be spent to immediately follow up an action with another action. This is how you can unleash your inner John Woo as you chain together actions in rapid sequence. Chasing down an enemy, dodging bullets, tackling them, roughing them up, and then beginning your interrogation can all happen seamlessly through spending momentum.

A bounty of follow-up rules and stats for gear exist, mostly due to a need to support this action economy. I find this a little unfortunate, as my tastes over the years have begun to move further and further away from RPGs with gobs of stats and tables. However, in this case the action economy is necessary to capture the hyperviolent action that works so well.

Chaining actions, pushing momentum, and swinging the spotlight around the table as your team of cyborg detective hackers and broken beat cops take the fight to corrupt mafiosos in the shadows of a neon pink floating city is really fucking cool. While this necessitates detailed stats for everything, it’s well worth it for capturing the unique vibe.

Hard City

Like Other Cities, only More So

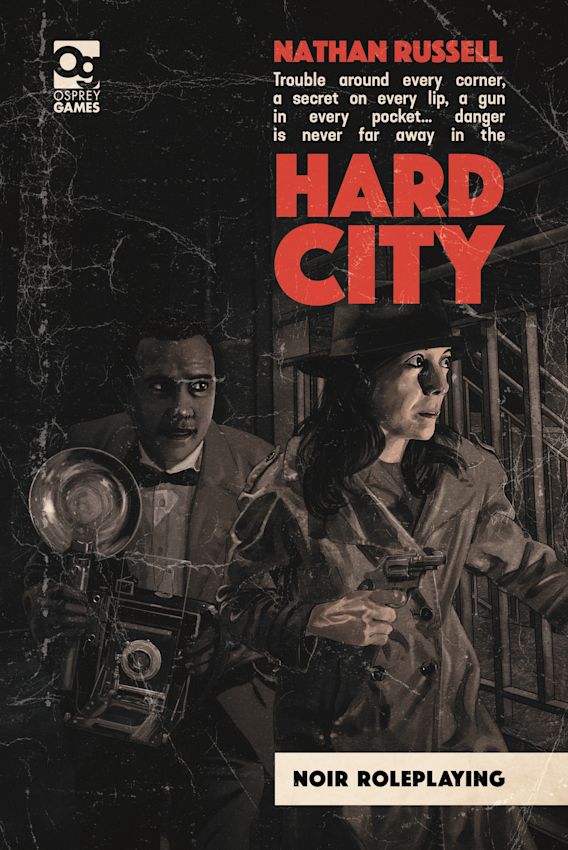

Nathan Russell’s take on noir is classic. The cover features two hard-boiled investigators creeping through their environment, revolver and flash-bulb camera in hand. Hard City is not about any one city, just the city and it’s likely your city will become as much a character as any player’s sheet.

As Hard City isn’t constructing a whole new world like Crescendo of Violence, more of the book is given over to crafting a moody feel. This is pure classic noir, with familiar locations like “The Waterfront” or “Downtown” serving to put you exactly where you’d expect to be. Accordingly, Hard City can be set anywhere from San Francisco, to Chicago, to your local city. As long as there folks being downtrodden and folks doing the trodding, you can weave a story.

A Narrative Mechanism

In a sharp contrast to Crescendo of Violence, Hard City has one of the most open and narratively flowing rulesets I’ve come across. There is a dice resolution system—a pool of offsetting Action and Danger Dice are rolled and any remaining Action dice form the resolution—but it takes a firm backseat to a narrative word-based system of Tags.

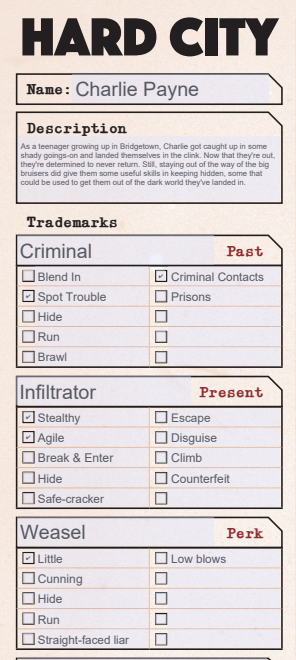

Tags are aptly named, as they function as a sort of narrative metadata layered over the entire experience. Classes as most of us are used to are not featured in Hard City. Instead, players select a few Trademarks (themselves Tags) to define their characters Past, Present, and Perks. These Trademarks come with lists of positive and negative traits but they are notably completely open to modification.

My character might be an Investigator who comes with the traits “Investigate, Notice, Interrogate” and drawbacks of “Personal Code, Hard Drinker, Reckless, and Heart of Gold” but it’s entirely within bounds for me to cross off half of those and reshape my Investigator into something different.

Tags are everywhere, and feed into all the rolling and resolution in the game, but are never prescriptive. They are narrative mechanisms. Their existence should prompt you and the GM to consider the repercussions, whether the tag refers to an item or a person. There are no explicit rules for sneaking or sound, but pistols are Loud so using one should reflect in the story. There’s no such thing as a Bribe check, but Bartenders have the tag “Knows a Guy” and my Past Trademark is High Society which includes the Money trait so anyone can put two and two together.

Tags can even emerge from the story itself. Moxie is a resource that can be spent by players to modify rolls or react to the scene with a voice over. Without getting prescriptive, the instructions say that elements from this Voice Over can become Tags attached to the characters or locations present.

In a way, Tags exist as a shared language between the GM and the players to determine to them what is relevant about any person, place, or thing. While it initially takes a minute to wrap your head around it is remarkably effective at unlocking the communal narrative element that I love so much about RPGs.

It does, however, put an awful lot of trust in the players and GMs to manage it. There is minimal structure to the rules which can mean that things get unwieldly quickly. When anyone can justify anything narratively, players can easily turn their flawed gumshoes into superheroes. Crescendo of Violence‘s red and green tokens force you to take the bad and good together but Hard City depends on everyone at the table wanting to tell that kind of story.

When it clicks, however, it’s amazing. I love the freedom the Tag system provides and relish the way it gives players control over stories. A communal story is my ideal form of roleplaying and despite having a GM Hard City enables that with aplomb.

The Mystery

Because both games are noir at their core, they both excel at telling similar stories. Mysteries full of red herrings and double dealing are what you’re looking for. The catch, however, is that these are very difficult stories to create.

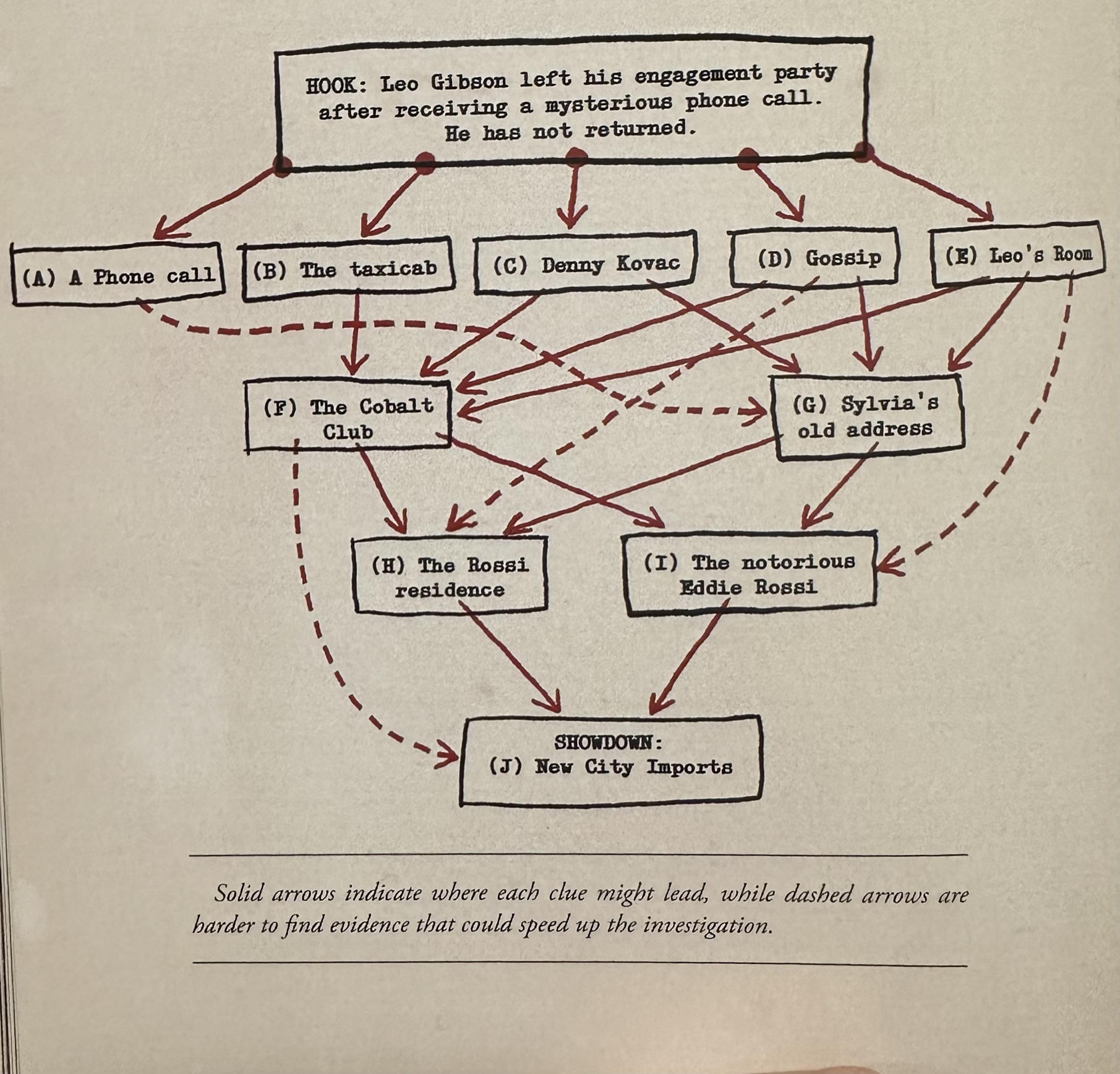

Mysteries have long been a bit of a stumbling block for DMs. The goal is for the players to solve the mystery and enjoy it, but figuring out how and where to weave clues is a challenge. Twists that don’t feel unfair, false leads that seem clever in hindsight, or even just basic facts left hidden due to bad rolls are hard to deal with.

Because of that, I have to tip my hat to Hard City. Both books provide a basic structure to mystery cases but Hard City spends quite a bit more time explaining how to lay them out and move characters from stage to stage. It also provides a full scenario and breaks it out into the same elements it recommends in mystery construction so you can see how the planning notes turn into a story.

That’s All Folks

Noir is classic for a reason. The heroes and anti-heros of dingy jazz bars, synth or traditional, are timeless for a reason. Both Crescendo of Violence and Hard City take different approaches to the genre and will deliver completely different experiences. Crescendo is action packed and glitzy, Hard City is deeply narrative and amorphous. Which one is right for your table will depend on the story you want to tell, but I can easily and firmly recommend them both.

Thank you to Osprey Games for providing copies of these RPGs for review.