Star Trek Adventures (STA) is turning seven years old in August, and Modiphius is celebrating with a brand new Second Edition of the game. There aren’t a lot of major changes, but the systems have been honed and revised to be more streamlined, and there’s a whole new emphasis on making each player the star of the show by putting them in charge of how and when their character changes, and letting them mechanically influence the details of every scene they’re involved in. Let’s see if players will boldly go on this journey with Modiphius.

Thank you to Modiphius Entertainment for providing a copy of Star Trek Adventures 2nd Edition for review.

Character Creation and Development

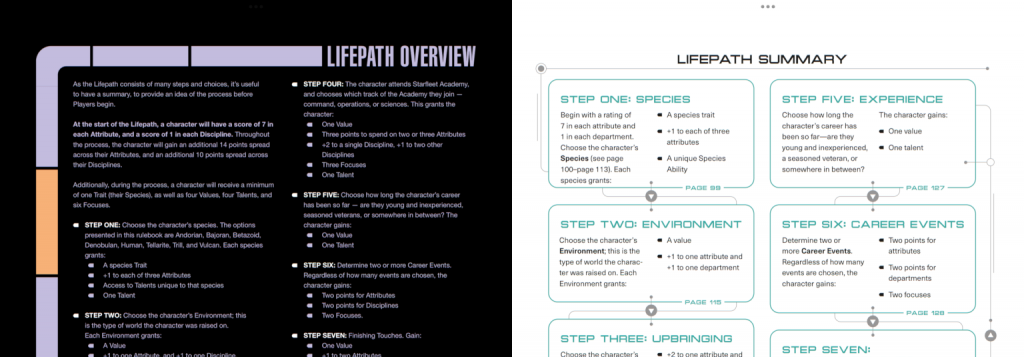

Character creation will feel straightforward to anyone with RPG experience, and easy to pick up for any first timers. There are two methods of character creation covered in the book: lifepath creation and creation in play. If you go with lifepath creation, you go through a series of stages making choices for your characters’ background (species, homeworld, education, etcetera), and at the end of the process you have a complete character. If you decide to go with creation in play, you decide the bare minimum before the campaign begins, determining attributes, species, the rating for two departments, and a single value (we’ll talk a lot about values later, they’re important). Everything else about the character is determined by the player when they come up during the course of play. For example, when asked to roll using a department that hasn’t been given a rating, the player can then assign a new, permanent rating to it. Both of these methods make the player start building their character with an eye to the setting and how they fit in it, which gives a level of buy-in that’s important for making the rest of the games’ systems work well, as many of them need a lot of player input and willingness to creatively influence the game session beyond just playing their character.

There’s a fairly standard six Attribute spread covering the normal things like fitness and reason. Instead of skills the game uses six values representing different Starfleet departments like Security, Engineering or Medicine to reflect a character’s training. Adding these two values together will set the baseline difficulty for most tasks, so it’s important for a player to make sure their character is proficient in the areas they’d most like to use in play. For example, you might use fitness + security to set the target for a roll to punch someone, or insight + engineering to figure out why life support is losing power.

Aside from those basic stats, the player assigns their character Traits and Values. These are the more freeform parts of character creation. Traits are words or phrases that describe something about who the character is or what they do, like “Human,” “Starfleet Officer,” or “Bartender.” Values are similar, but they reflect a character’s internal belief system. These can be hard to come up with on the spot, but the book gives a lot of examples in both a generic list and more focused selections in the write-up for each species to give players guidance on what’s expected. Examples of values given include “I can make something from nothing,” “spoiling for a fight,” or “I am my own keeper.” Both traits and values can be interacted with for various mechanical benefits and penalties, but I believe their main function is to keep the players engaged with the roleplaying aspects of the game, and to give the GM guidance on what kinds of challenges to put in a player’s way. If a player takes “Exploration runs in the family” as a value, they’re probably not going to want to be in a campaign where they hang out on Deep Space Nine the whole time.

Character advancement in STA is entirely player-driven. Instead of the gamemaster awarding experience whenever the crew overcomes an obstacle or completes a certain number of encounters, advancement is driven by characters using or challenging their values. During a mission, when a player interacts with one of their values, they note it down on a provided “personal log” or just take notes. Then, in a later mission, if the player uses that same value, they can tie it back to the events of the first mission and explain how that experience continues to shape their character. This is called reaching a milestone, and it allows you to improve your character in a number of ways, like improving attributes, gaining traits, or even improving your starship’s characteristics.

For longer term advancement there are “character arcs,” which function as a more powerful version of a milestone. If a player uses a value, and they can point to a previous milestone using the same value, they can complete a character arc, which confers stronger advancement choices than a normal milestone. These arcs can only be completed rarely, and get harder each time, requiring more and more missions to be referenced each time one is claimed (starting at 3 missions, then 4, and so on).

For more immediate advancement, there’s a reputation system that keeps track of how well regarded you are in your faction, organization, or general life if you’re a civilian with few formal ties. For example, a Starfleet member gains a positive reputation if they solve issues without physical conflict or save the lives of innocent people, while they take a hit to the value if they lie or otherwise act unethically. Being a reputable member of Starfleet leads to the player being able to spend points to buy their character medals and awards, such as the Christopher Pike Medal of Valor, which give various benefits in play. There are also punishments given if a character’s reputation falls too low. These awards or penalties are rolled for after every mission.

Mechanics and Conflict

Star Trek Adventures uses a version of Modiphius’s 2d20 system, where the goal is to build a dice pool of 20-sided dice and then roll under a target number with as many of them as possible. Target numbers are generally set by adding together the value of a character’s relevant attribute and department, with the baseline difficulty for a character with no training in something being around an 8 or 9, and an expert character rolling against a 14 or 15. If a player rolls under the combined number they get one success, and if they roll under the chosen department they get an additional success. Difficulty is further set by designating a number of successes needed to accomplish a task.

There is a meta-resource called momentum that is generated by a player rolling more successes than they need to accomplish a task, which can be spent immediately for benefits or saved for the entire party to use later. Momentum is one of the ways to get extra dice during a roll, allowing players to attempt high difficulty rolls, and it’s important enough that the game encourages gamemasters to let players roll against a difficulty of 0 at times so that every success they roll will give them some momentum. Players can also get extra dice or benefits by giving the gamemaster threat, a different currency that is like momentum but that can only be spent by the gamemaster to make the players’ life worse. This allows players to make high-risk gambles and ratchet up tension on their terms, and not just have things dictated to them.

Each scene during the game has its own set of traits, and players can use momentum and actions to change them or add new ones. When exploring a derelict spaceship, for example, the scene might have the trait “Powered Down”, which would make tasks needing energy either more difficult (opening a door) or impossible (accessing a computer log) until a player either performs a task to restore the power or spends the momentum to change it. Players can also add new traits to turn things to their advantage, spending momentum and narrating their actions. For example, a player might decide to disable the lights in a room, giving it the “pitch black” trait and making it easier for them to hide from a creature or enemy that’s searching for them.

STA explicitly defines three types of conflict in its rules: Personal Conflict, Starship Conflict, and Social Conflict. The first two of those are your standard combat subsystems, with rules for attacking and defending and things like that. The Personal Conflict station is concerned with allowing players to escalate and de-escalate conflict as needed (setting phasers to stun or lethal, for example), while Starship Conflict section has mechanics for what each station on the ship allows a character to do, but for the most part the rules are of the same kind that you’d find in any mainstream RPG.

The Social Conflict rules are interesting because they attempt to give mechanical weight to what would often be handled strictly by roleplaying, or maybe with a skill check or two. I’m not sure it entirely succeeds at this, but let’s break it down. A Social Conflict revolves around one character attempting a persuasion roll to get another character to do something for them. This could be anything, ranging from doing a favor to acknowledging a belief. Players get to use a variety of techniques to influence the difficulty of this role, like presenting evidence of a theory, coming up with lies, or intimidating another character. There’s a lot of flexibility here, but I’m disappointed that everything in the system still culminates in a single roll. You can do all the set-up and planning in the world, but if you roll a 20 the other character can still just ignore it all. This is an easily DM’d around problem, but it’s still not a great state for the rules as written.

Production Values

The greatest rules in the world are useless if you can’t find them, and STA avoids this problem by having both a fantastic layout and a thorough index. The LCARS-inspired layout of first edition is gone, replaced with a sleeker layout that still uses a lot of text boxes and callouts but looks much more modern. This is a trend that continues from the later releases of first edition, and I’m glad they continued to refine the look. The color palette is used masterfully, with consistent, specific colors used across the book to represent in-character, in-universe text or examples of play and make sure you can distinguish them from rules content at a glance.

Attention to small details shows when looking past the design ideas to the nuts and bolts layouts as well. Each different section of the rulebook has different colors, so it’s easy for everyone to remember that if they want the main rules, that’s in the red section, while the gamemastering chapters are over in the yellow section. The “subchapters” are kept from the first edition, but this time every single one of them starts at the top of its own page, instead of just sort of falling in place wherever the text dictated. Each species write-up fits on its own page so you never have to flip around. These are all small things individually, but they add up to a very pleasant reading experience and make the book simple to use during play when you want to spend as little time as possible paging through things. The index is four pages long and very thorough, but to be honest the book is laid out clearly enough that I didn’t really need to use it outside of when I was specifically looking at the index to see if it was any good or not.

There’s also a ton of great art in the book, so if you’re curious about what a specific type of starship or a certain alien species looks like there’s probably an example of it in there somewhere. I’m glad they didn’t go the “cast photo/screenshots of the tv shows” route, as that always looks pretty low rent to me.

Is It Star Trek?

I think so! While there aren’t a bunch of rules or advice explicitly telling gamemasters and players to act like they’re in the middle of a Star Trek episode, most of the rules are implicitly about doing just that. From character development being couched in the language of “character arcs,” to each character having a reputation score that, in a Starfleet centered campaign, boils down to showing how good they are at being a member of Starfleet, which in turn is mostly based on acting like they’re on TV. My favorite example of this is perhaps that if a player ever decides to use lethal force, they’re required to add some threat to the gamemaster’s pool. This is a great way to handle the idea that Starfleet crew aren’t ever supposed to want to hurt people, and if they’re forced to, something has gone very wrong and people are in mortal danger.

For existing Star Trek fans, there’s a lot of stuff to dig into. There are a lot of different alien species and a bunch of starships in the book, all mechanically different from each other. There’s advice for running pretty much any type of campaign you’d like to, from any of the TV settings or something more esoteric that focuses on time travel, or the evil mirror universe that pops up on occasion. For those new to the IP, all of those settings are well explained and they have good examples for what a crew might do in them and why they would be exciting to play in.

Is It Good?

Yes. The second edition of STA is more of a refinement than a revolutionary change to systems of the game. The years of experience gained from the game being out have been used to iron out most of the worst flaws first edition had, and the switch to making character advancement and much of play player-focused makes the game more fun, provided you have a play group that likes to influence the setting of a scene and handle more of the creative world building for an adventure than normal. If your group, or someone in your group, is on the quieter side or shy in social situations, there are a number of mechanics that won’t work as well as they’re meant to and the experience could be awkward or disappointing because of that.

The licensed nature of the game also helps it work well as a bridge from more traditional RPGs like D&D or Pathfinder to more narrative and player-driven games like Blades in the Dark. If the group is new to the idea of doing something like establishing a scene’s traits, the game eases them in by giving creative aids like the “Treknobabble table”, where a engineer player can just roll on it to establish that, say, they’ve “amplified the isolinear tachyon field stabilizer” and therefore players in the scene get a bonus to something they were trying to do. Having a bunch of examples from decades of TV and movies takes a lot of the pressure off of players when they need to come up with an idea that sounds like it fits the setting.

I’d recommend STA 2E to both Star Trek fans and fans of science-fiction roleplaying in general. There’s a very nice engine handling the mechanics, and with some tinkering to things like the reputation tables you can make the game play any way you want, so the group isn’t stuck trying to uphold the values of the Federation when they would rather be playing it more like a comedy or traditional action game.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.