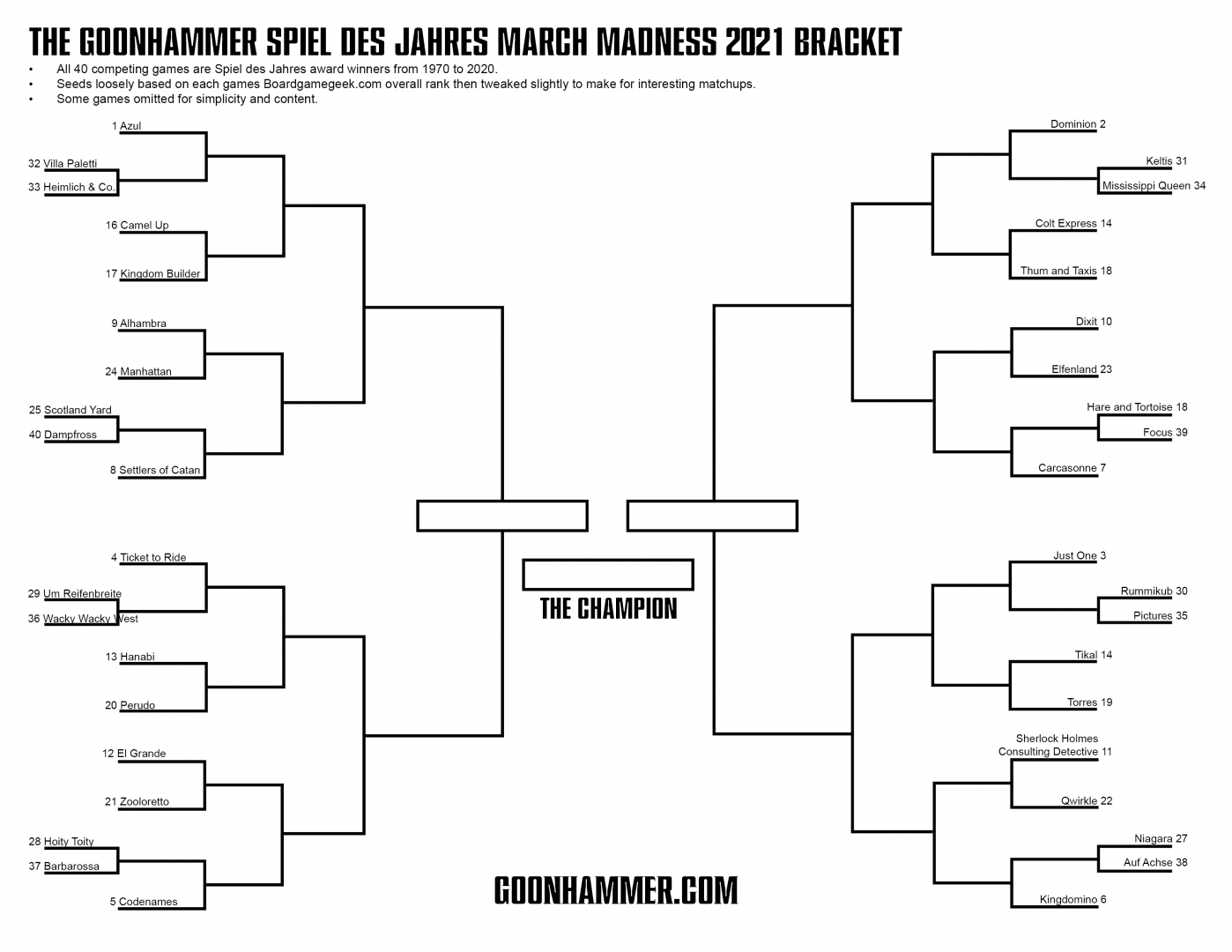

Wondering what this is all about? Check out our previous articles introducing the bracket and breaking down the Northwest Region’s “Play-In Games”.

The NCAA Men’s March Madness tournament is a 68-team tournament played every March, culminating in the crowning of the Men’s College Basketball Championship. It is a single-elimination tournament that takes place across the country; early rounds will see up to 4 games being played simultaneously. For die-hard college basketball fans it is like Christmas. It has not always been 68 teams, however.

Beginning in 1985 the NCAA Tournament expanded to 64 teams. Participants are divided into teams that receive “automatic bids” and teams that received “at-large” bids. The winners of the 32 Conference Tournaments are given automatic bids, while the remaining bids are given to teams based on season performance. For the teams in many conferences the only hope to go to the big dance is winning their tournament.

In 2000, the number of conferences expanded and rather than cut an “at large” bid, the NCAA created what became known as a “play-in” game. The two lowest seeded teams (always automatic bid winners) would play in a game a few days ahead of the start of the main tournament. This game became a popular appetizer, and so the NCAA expanded the field to 68 teams in their quest to fill their coffers with as much money as possible, and support the student-athlete or whatever they claim their mission to be. Now, each region has two teams vying for a spot in the “main” bracket; a couple teams compete for a 16 seed and a couple teams who squeaked in with at-large bids compete for an 11-seed (give or take a seed).

Our exploration of the Spiel de Jahres winners begins with the Northeast Region’s “Play-In Games”. These award winners certainly deserved their awards at the time, however it’s unlikely that they’ll take out any of the powerhouses. You never know, however, if there is a UMBC lurking…

Keltis

Keltis, the 2008 Spiel des Jahres winner, is a multi-player re-implementation by Reiner Knizia of his 1999 two-player classic Lost Cities. To North American audiences, Keltis is almost certainly better known as Lost Cities: The Board Game, which broadly tracks (minus some rules changes) with Keltis.

Keltis is a set collection and hand management game, like Lost Cities, in which the players are working to move their pieces along pathways in an attempt to earn victory points. The further up a particular path a player moves, the greater the reward. On their turn, a player plays a card out of their hand allowing them to move their piece along the path to the value of the card they played. Initiating a stone onto a path, however, places the player in jeopardy of taking negative victory points if the player is unable to move the stone very far. As a result, again, like in Lost Cities, there is advantage in concentrating one’s effort on just a few pathways.

I have played Lost Cities hundreds of times and consider it one of the greatest of all two-player games. This re-implementation is just as good. Like all Knizia games, Keltis is quickly paced, very easy to learn, surprisingly strategic and fun. Having said that, the theme is really there to provide a little ambiance and artistic direction to what is essentially a cleverly designed mechanic.

There’s a certain parallel between this game and Paul Newman’s Oscar win in the 1986 for “The Color of Money.” Keltis is a great game, deserving of its 2008 win, but in a year that saw Stone Age and Witch’s Brew get nominations for the Spiel des Jahres and Agricola getting a special award for “complex game,” it definitely feels like the committee was considering Knizia’s previous designs. History will certainly show that games like Modern Art, Tigris and Euphrates and Ra were perhaps even more worthy than Keltis was…and it certainly was!

Special thanks to Jon Cassie for contributing the Keltis write up.

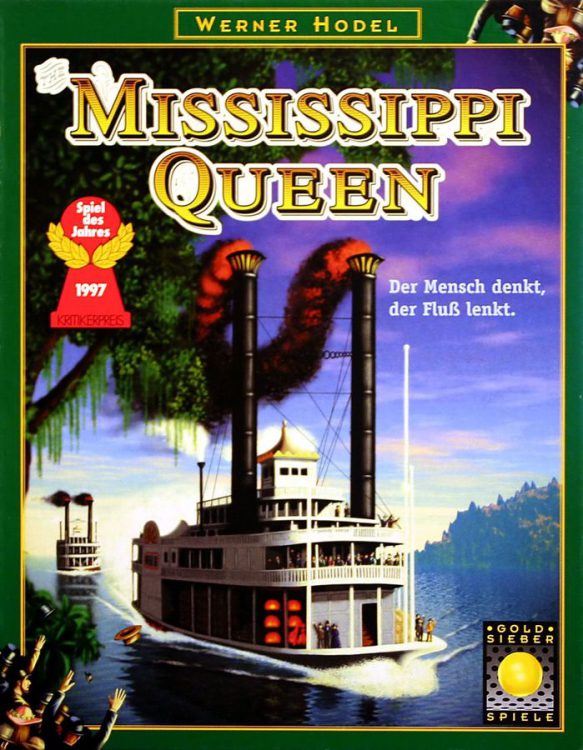

Mississippi Queen

Mississippi Queen is a racing game—but it’s a racing game where you are racing large, slow moving paddle wheelers. This is just one of the things that’s so great about Mississippi Queen: you’re racing things that weren’t really designed for racing. You’re trying to get your paddle wheeler down the Mississippi first, but, in order to win you have to pick up two passengers along the way. This means you have to slow down to pick up passengers and speed back up. So, it’s a racing game, where you’re racing things that you shouldn’t race, and you need to slow down to a near stop twice.

Paddle wheelers start off moving slowly – one hex per turn. On your turn, you can adjust your speed up, or down, by one: paddle wheelers have a maximum speed of six. Then, you have to move a number of hexes exactly equal to your speed, and you may make one, but only one, hex-face turn. You start the game with six coal, and you may spend coal to further adjust your speed or make an additional turn. There are just enough choices you have to make during your turn to keep things really interesting.

The tension in the game comes from the way the Mississippi River is set up: the river is represented by 12 river tiles, each about four hexes long, but the river unfolds as the game goes along. You don’t set up the river at the start of the game, more tiles are added as the game goes on. This means you can plan, but only a little bit. You have balance moving quickly to get to the finish line, but slowly enough to both manoeuver around hazards in the river and pick up your passengers. This really strikes the balance, for me, for just enough thinking: you don’t need to over-analyse everything in the game, but you do need to do a bit of planning. Of course, your planning can be totally ruined by a new river tile with a bunch of floating logs in it appearing.

Mississippi River is one of those games that’s greater than the sum of its parts. It’s tense, it produces a lot of laughs, and your best laid plans can fall apart at a moment’s notice when your boat crashes into a sandbar or some floating logs

Special thanks to Tim Fowler for contributing the Mississippi Queen write up.

Our Winner – SLOW BOATS

Who would win: Reiner Knizia, one of the most decorated and celebrated board game designers of all time or 3 paddle bois playing bumper boats down The Big Muddy? With apologies to the good doctor, we’ve got to give it to the boats.

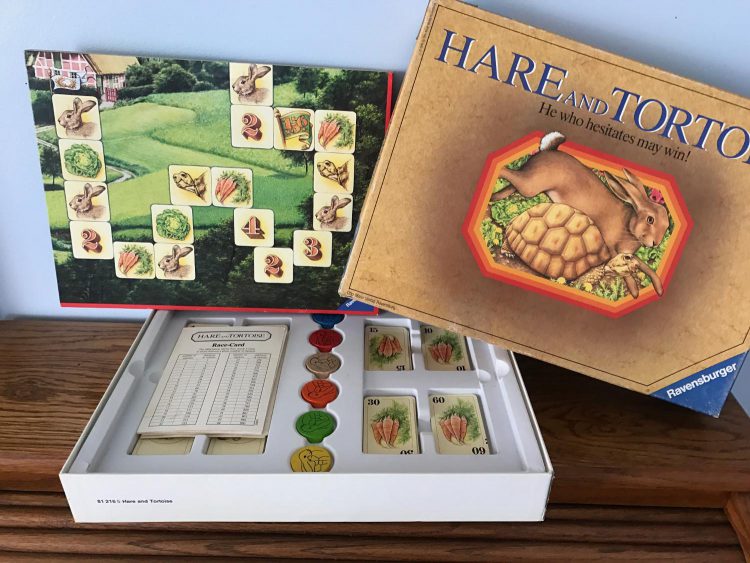

Hare & Tortoise

Another racing game, Hare & Tortoise was the winner of the very first Spiel de Jahre award. As the award has done for countless titles over the years, it transformed Hare & Tortoise into a perennial seller that remains in print today both as Hare & Tortoise (Ravensburger) and as Around the World in 80 Days (iello). In Hare & Tortoise players take on the role of the Hare and must attempt to speed their way to the finish line.

The track is a simple straight line, however it has some wrinkles to space layout. The first is that Tortoise Spaces pepper the track; no player’s Hare token can stop on a Tortoise space. You’re also restricted from sharing a space with other players. Alone this wouldn’t make Hare & Tortoise feel special but it’s the actual movement that gives this simple game its edge. Each player begins the game with a handful of carrot cards that must be spent to move along the track. Moving 1 space costs 1 carrot, but moving 2 spaces costs 3, moving 3 spaces jumps to 6, and so on. The faster you go the more cards you’ll burn.

In order to replenish your staff you’ll have to move backwards to a tortoise space, stop on a lettuce space and “eat” one of the lettuce cards you begin with, or take a calculated risk. Scattered across the track are numbered spaces. If you begin your turn in a numbered space that matches your position in the race, you’ll get 10 times your position in carrot cards. Like the lettuce spaces this can provide an accelerant to those players further back in the race though your opponent’s can conspire to ensure you do not receive the bonus…if it is advantageous to them.

This simple game play leads to tense situations where players are balancing a couple of different considerations. While the decisions aren’t particularly deep, they do branch which helps this game punch above its weight (and can unfortunately contribute to some analysis paralysis as players follow the branching mathematical pathways). Hare & Tortoise certainly holds up these days. While it’s simple, simple isn’t always bad. The Spiel has always valued approachable games and it’s clear how Hare & Tortoise earned its award.

Focus

(To be read in your most Matrix Movie Voice): In a way, isn’t every board game a mere abstraction made from cardboard, wood, and plastic?

Perhaps. But truly abstract board games—with or without the decorative slipcovers that pass for narrative or theme—boil down to the same base elements: math and the moving of pieces. Though not as ancient as Go or Chess, the SdJ-winning Focus is a simple abstract with deep strategy that feels similarly timeless. Focus is the oldest SdJ winner in the field; designer Sid Sackson received the 1981 award 20 years after designing it. Given Mr. Sackson’s huge influence in modern board game design (Acquire, Can’t Stop, I’m the Boss) his win could also be construed as a lifetime achievement award.

On the complexity scale Focus snuggles nicely between checkers and chess. On your turn you’ll move two different ways: 1) move one of your pieces one space onto an adjacent space. Any amount of pieces can share the same space, and if you ever stack your piece atop another piece you now control that stack and it can move as a hive-mind monolith. Or you can 2) move a stack that you control an equal number of spaces as the number of pieces in the stack (2-piece stacks go two spaces, 3-piece stacks go three, and so on). You can also break up and move partial stacks to make smaller moves – but this may “free” previously controlled opposing pieces. The object is to assimilate all of your opponent’s pieces (via math, moves, and stacks) so that there are no pieces on the board they control or can move.

Focus wasn’t even produced as a sellable game at first; Mr. Sackson initially published the game’s rules in a 1963 issue of Scientific American magazine. You likely could play it right now with ingredients from your own game collection: a standard chessboard or checkerboard and two full sets of checkers or other stackable stand-ins is all you need. Ironically, across the game’s sixty-year lifespan it’s been out of print more years in print – because like a deck of playing cards, Focus is more of a game system than a game. There’s no need to rely on a boxed deluxe edition. But because of Focus’s abstract pureness and “minute to learn, lifetime to master” charm, this classic game may be out of print but has never been out of style.

Our Winner: Hare & Tortoise

Unlike many of the winners, Hare & Tortoise has stayed in print it’s whole life. The Around the World in 80 Days edition even has quite a deluxe feel. We like the accessibility and ease of play, and the cute theme means you can play it with your kids as well.