When Wizards of the Coast created a collectible card game, they were inventing something with potentially inherently toxic characteristics. The 30-year history of magic has included a lot of headlines about the real world value of certain magic cards, largely because the original print runs were small, and many problematic cards were printed in the early years of Magic, long before its designers understood the game they were creating, which would be fundamentally unbalanced.

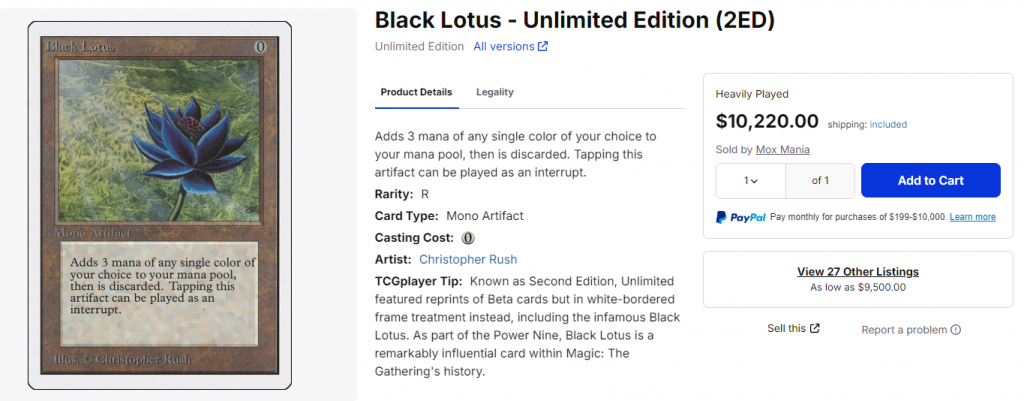

Black Lotus remains the most glaringly obvious example.

Magic as a game has always had to exist in an uneasy state of tension between its status as a game and its status as a collectible product. In those early days the idea was that players would buy a couple of starters, a few boosters, and have a collection to build from – limiting their ability to build based on what they owned. As the game matured and competitive deck construction rules were codified, this changed, and players were expected to assemble decks using multiple copies of the same card. Soon, the collectability became a barrier between the player and the “real” game of Magic, i.e. the game that occurs when players can build any deck they can imagine.

The original rules of Magic called for 40 card decks with no per card limit, because neither Richard Garfield nor anybody else involved foresaw the arms race that would occur when people realized that, in Alpha, the best deck list is mathematically something like 14 Black Lotuses, 25 Timetwisters, and 1 Lightning Bolt. If you go first you Timetwister until you get a Lightning Bolt, cast it, and keep Timetwistering until it comes back.

There’s no game there; it’s just applied statistics. A mint condition version of that deck in 2024 would cost something like One Million Three Hundred and Twenty Six Thousand American Dollars. Or more or less, since there really aren’t 25 alpha Timetwisters you can even buy kicking around on the open market at any given time. And just so we’re clear: That’s for 40 pieces of cardboard.

This is not a good thing. Obviously it’s kind of irrelevant what the optimum make-up of an Alpha-legal Magic deck is other than to make a point – the point is that the price of the cards has gone way up.

These cards were always expensive; as early as 1995 a Black Lotus was already the most expensive single card in any CCG, priced at $300. But those costs skyrocketed thanks to speculators and communities and movements like mtgfinance, which is an abomination. I am not an investment advisor and this is not investment advice, but I can build a Black-Scholes model from scratch, and in fact I used to hedge mortgage servicing for a bank as part of my job, and I can tell you that my exposure to cardboard in my retirement plan will be zero.

Magic cards, and other card games, and games in general, should not be treated as an investment and when speculators drive the value of pieces from games it’s toxic for everyone who wants to play the game. Kids who want to buy cards can’t afford them at inflated prices and even precons are increasingly out of their reach as people hoover up certain Commander decks and they begin selling above MSRP long before their actual public release dates, usually because the price of individual cards in the precon outweigh the product cost. Dockside Extortionist was a perfect example of this, people saw how broken it was almost immediately, and within a month or so of release the Mystic Intellect deck. Which meant that they sold out nearly immediately, because you could essentially get 99 cards for free and make a profit by buying the deck and selling off the dockside.

We’re now at a point where you can watch the price of Commander decks rise before the precons even release.

So the fact the rules committee did something really good, and banned several overpowered, expensive cards, is awesome. Because it helps break this cycle of speculation, wherein people are buying cards simply because the price of them always goes up. I myself have been guilty on occasion of thinking that I should just buy up cards I know will be good, pre-ordering a bunch of starters, and parting them out later, because it’s essentially free money for flipping cards, and I hate the thought. It really ought to have nothing to do with a game like Magic.

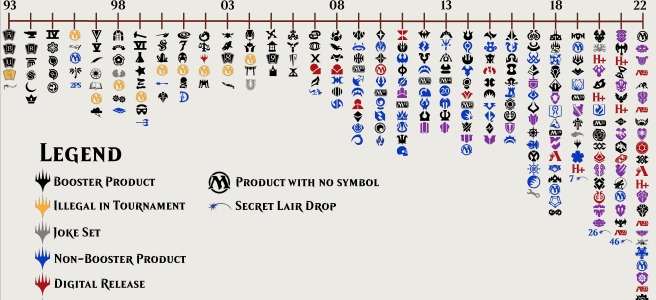

A huge part of the problem of course is Wizards of the Coast themselves, and their parent company, Hasbro. With the demand for increasing revenue gains year-over-year, Hasbro/Wizards have been more than happy to lean into these markets, both treating Commander as fertile ground for half a dozen or more new products every year, and leaning into the speculator/collector markets with new card treatments, booster types, and secret lairs. The result has been an explosion of products, with a decrease in overall quality and an increase in the number of banned cards. And of course, more Secret Lair drops, now with limited print runs to maximize collector value. Up, up, up.

Wizards’ relationship to the secondary market has always been one of an uneasy alliance, with the company having to both acknowledge that the toxic speculation bubble has been fueling card purchases forever and that it’s bad for the players and the game. But the game only matters to Hasbro insofar as it leads to sales. The company has taken great care to not overly disrupt the secondary market, revising the Reserved List policy after outcry in the late 2000s and carefully choosing which cards it reprints, and at rarities designed to help the originals hold their prices. Choosing to ban cards has always been a move at odds with this policy, as doing so can erode the misplaced confidence speculators have that card value will always increase, so they should buy, buy, buy.

If the rules committee does another round of needed bannings, it will almost certainly break down the cycle of people just assuming they can (and should) buy cards now because the price will only go up. Magic cards shouldn’t be considered an investment but even if you do, it’s worth noting that Magic cards, like all investments, carry risk associated with them. You are essentially making a bet that Magic will still be around, and that those cards will be playable and good in the game’s formats. You risk that your cards may be banned, reprinted, supplanted by other, superior cards, or just ruined by an errant glass of water. But it’s worth repeating that the price of a given card is heavily linked to its utility in the game, and across multiple formats. So if people expect (which they should) truly broken cards to be banned at some point in the not too distant future, then they wont be hoovering up tons and tons of copies to flip later.

Which, in and of itself, is tax fraud. Selling collectibles at a profit is subject to either ordinary income tax or long-term taxation rates. I don’t particularly care that people aren’t filing their Form 8949, but the value of “Magic holdings” (and it is disgusting that is a phrase) has gotten so high that it risks the IRS taking notice of the situation and taking action. Can you imagine the hassle of having to report the cost basis of a starter you bought, friendly local game stores being forced to report single sales or any of that rigmarole being involved in wanting to sit down and play a few rounds of Magic?

It would suck. And the current situation, it sucks. And the Rules Committee stepping up, and doing something about it, for the long-term health of the game, is an unequivocally good thing. But like many good things, it was immediately met with a host of challenges and threats from the game’s most toxic members, people for whom a card’s aesthetics and play value hold no meaning beyond what they add to the card’s sell value.

The preceding part of this article was written before the rules committee was forced to resign over death threats.

To put this in context: Death threats over banning four cards that were unequivocally good, and needed bans, to improve the health of the format, the playability and fun of games, and to remove some of the barriers between players with lost of money effectively in the game. Barriers which were specifically between those players who bought the cards a long time ago, and value their decks at what they paid for them, instead of what they were worth at the time of the bannings, and newer players who had not acquired those cards.

Commander is an awesome format to whip out an Ebon Praetor in. It’s a lot less fun to whip out a Chains of Mephistopheles. The fact that people threatened physical harm to others hyperbolically (we certainly hope it was merely hyperbole), over their cards being banned is a real sign of just how toxic the Commander community can be. And it’s impossible to untangle that toxicity from the financial and speculator aspects – many if not most of the people who expressed outrage over cards being banned in what is ostensibly a kitchen table format possessed multiple copies of the banned cards – and many were more than happy to post photos of their collections – as they expressed their anger over the loss of value. These players were upset first and foremost because they planned to profit off those cards one day, or at least derive pleasure from the slow creep in value of their Magic collections. Nevermind that such value isn’t realized until the cards are sold at a profit; the loss is a temporary, paper one but the threats remain.

And the value of those cards should have nothing to do with playing the game; decks should not be regulated by price tag. Money cannot and should not be the balancing factor for a game. As players, we accept the collectible aspect as a barrier because it notionally carries some upside – opening packs is exciting, limited formats are fun, building collections can be rewarding – but when the scales tip too far and the gulf becomes too deep, the scales on Magic tip from “collectible card game” to “tedious gacha game” and the loot box style mechanics of booster packs become impossible to ignore.

Magic is a game which can easily survive the loss of its speculators and the secondary market; it cannot survive the loss of players. Wizards can and should continue to focus on bans which improve the health of the game for players, even – and especially, we’d argue – at the cost to speculators and collectors.

At the very least, it’s worth teaching them to assess risk.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.