These are dark times indeed. The Empire is riven by civil war where great factions vie for supremacy and the right to rule. Grand armies clash against one other, whilst the malefic forces of chaos and the greenskin tide move against them in their time of disunity. But you are no great general. You lead no army, no regiment, no garrison. You and your patchwork band of misfits are desperate. Hungry. And what better beacon is there for the desperate than Mordheim, the City of Damned? Destroyed in the fires of a divine twin-tailed comet, where revellers cavorted in the streets until their untimely demise at the dawn of the new millennia, it is now a monument to hubris. Only the foolish and the mad wander its crooked streets and plunder its haunted ruins for a chance at finding their fortune, or more likely, an ignoble death. Tell me traveller, do you have what it takes to test your mettle in the City of the Damned?

What is Mordheim?

Published in 1999, Mordheim is a fantasy skirmish game set in the Warhammer Fantasy Battles universe, written by Tuomas Pirinen, Alessio Cavatore and Rick Priestley. Set about 500 years before the events of the eventual End times (Also the year 1999 in universe) you played warbands of treasure seekers looking for fragments of ‘wyrdstone’ in the titular ruined city, fighting other warbands for whatever loot you could scrape together. What Necromunda was to Warhammer 40K, Mordheim was to Warhammer Fantasy. At release Games Workshop produced a cool box set with cardstock terrain and miniatures, and supported the six(ish) warbands in the rulebook, before slowly releasing additional content for the game, with new warbands, scenarios and even settings coming from yearly Mordheim annuals, Town Cryer (Mordheim’s own specialist magazine) and articles White Dwarf and Fanatic. GW went on to produce miniatures of some of these newer warbands, with models of everything from Pitfighters, to Amazon’s, to the Carnival of Chaos. By 2004 official support had mostly dried up in print and the game left the shelves of all but the dustiest hobby stores, though a few models continued to be released for the game until 2006, and some miniatures remained available to order through GW’s specialist games imprint until the broader Warhammer Fantasy setting was blown to pieces around 2014. The game turns 25 this October.

However, despite it being basically out of stock for over 20 years, this isn’t some sort of retrospective. This game is alive and well, surviving in the dark corners of the hobby, its dense multi-story ruins furtively glimpsed in gaming clubs, Instagram posts and homes around the world. This game is still fed and nurtured by a surprisingly committed community who are still producing content for it, continuing to bolt on additional house rules, scenarios and factions to create some grim palimpsest homunculus of a game. And to be honest it’s really easy to see why it’s so beloved. Beyond mere nostalgia, Mordheim still fills an attractive little niche that to my mind no other Games Workshop (or third party) game has managed to capture; a fun, gritty fantasy miniature game with a compelling blend of grimdark theming that permeates the setting, the campaign mechanics, and the rules themselves to create something that transcends a skirmish game and becomes a story generator.

What’s the Game Actually Like?

To play a game of Mordheim you’ll need to create a warband from one of the myriad available. You’ll normally start with around 500 gold coins, the currency of the game, to purchase your warband. This will normally include 1-6 heroes (including your warband leader) and some henchmen. All your models have the classic array of stats that anyone who’s played a GW game in the past 20 years will be familiar with (Movement, Weapon/Ballistic Skill, Strength, etcetera) that inform what you need to roll to do anything in the game. You can then equip your warband with a mix of weapons, armour and equipment and send them into the depths of Mordheim to score some wyrdstone, playing one of several scenarios that pit you against other warbands scrabbling over the ruins. There you’ll take turns charging, moving, shooting, casting magic and fighting, trying either to complete some esoteric objective (like finding something and move it off the board) or beating the snot out each other until one of you loses 25% of your warband and fails your rout test, leaving the other the victor.

After each game you’ll roll to see if any of the models that went out of action survived, died, or were brutally injured. Any that do survive gain experience; with henchmen periodically increasing one of their stats with a small chance of becoming a hero and with heroes either increasing their stats or gaining new and powerful skills. You’ll also use any of your still upright heroes to search for shards of wyrdstone in the area they just fought over rolling a d6 for each and seeing what each hero contributes (the higher the better) with multiples representing special locations where you can get extra loot. Any wyrdstone you find you can sell immediately to gain more henchmen, equipment or hired swords (mercenaries that’ll fight for you, for a fee of course). Or of course you can stockpile it for a rainy day. Rinse & repeat. It’s a compelling little gameplay loop where you’re always trying to push your luck to get more XP, more wyrdstone, more loot, balanced against the brutal attrition that you’ll take actually trying to win any of these petty street fights, which will inevitably thin your ranks and cost you your meagre winnings.

Campaign Play and Emergent Narrative

To me, that’s where the game sings: Played as a campaign. To be honest, one off games are not good. The game design feels pretty dated; no alternating activations (just the classic, I do all my stuff then you do all your stuff, turn structure), the swingy probability space of single d6s to achieve things, and really limited comeback / imbalance mechanics. But taken as a whole with all the additional strata of a narrative campaign beneath it, it’s pretty easily forgiven.

One thing that’s very apparent in the design is the inherent customizability that comes out of both warband creation and play. When you create your warband you’ve got a list of weapons and armour that your warband can use, themed around the flavour of your faction, with humans having lots of flexibility and options with the more fantastical warbands being more limited. There’s a range of different styles of play in those options and every member can fill a different niche, allowing you to imbue a lot of characterisation through those choices, especially when the dice rolls are adding in an big element of randomness. Your hapless spear wielding henchman can pull you through game after game, whilst your hotshot bowman hero whiffs on every shot. You can of course equip every character in the most boring (efficient) way possible, but you’d miss out on the time that your blunderbuss mook suddenly downs three models in one shot and turns the tide of a battle you thought you were destined to lose.

This level of individuality also extends to all the horrific things that can happen to your warband. Whilst your henchmen simply die or do not die, heroes face a myriad of deadly consequences for going out of action. From losing an arm or an eye, you can also go mad, get robbed, get sold to the fighting pits, be horrifically scarred or make a full recovery and be back in time for the next skirmish.

On top of all the granularity that you can extract from your warbands faction, there’s also a suite of hired swords you can employ, adding their own character and special rules to your games. From Warlocks (a useful spell-caster) to Ogres (big beefy roadblocks) you can make up for your warband’s weakness or double down on their strengths, as long as you keep paying them that is. Yet another narrative strata in which to delve.

Setting

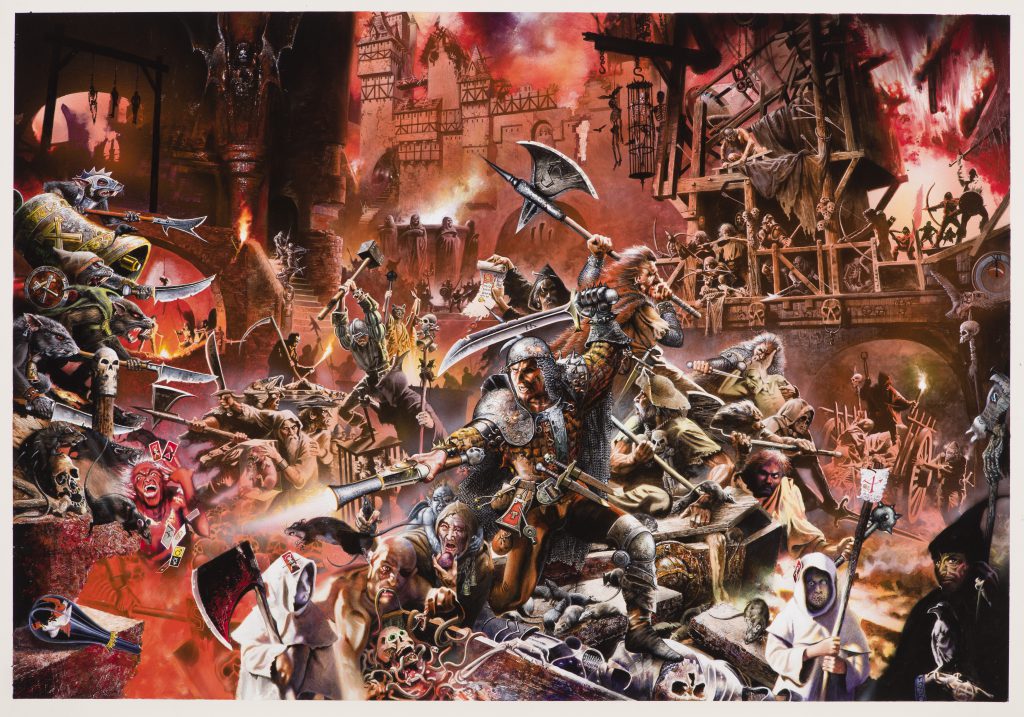

Beyond the mechanics, I think the setting of this game has been the source of its longevity. It’s something visible throughout the entirety of the game, from the Boschian box art by Geoff Taylor, to the literal physical presentation of its rules, with moody Blanchian vignettes and marginalia peering at you from every page, to the rules themselves, where everything is left to chance, to randomness, where everything feels like a risk.

And that’s the pitch right there. You play as a band of desperate losers, literally the most hapless downtrodden folks in the setting, who’ve been forced by circumstance or decree to scrounge around the burnt and broken ruins of a warpstone tainted city to look for bits of magically radioactive rock in the hopes of a better future. Beyond being strangely relatable (something something late stage capitalism), I think it adds a lot to the continued engagement in the game. In bigger box settings, you’re playing as the Best of the Best, the Cream of the Crop, the Big Kahuna. You’re the Stalwart Defenders of Humanity and Order battling the Forces of Chaos or you’re the Ravaging Horde and the Destruction of Man, conquering all before, Hail the End Times! etc etc. You can’t lose. You’re the damn protagonist. But. Say. if you’re a no good guttersnipe leading a band of rum coves and degenerate lickspittles, losing is your life. And when you’re a loser, every victory feels like a miracle. That’s what makes this game so satisfying.

But it can also be a double-edged sword. Sometimes Mordheim is unfun to play. Because the brutality is baked into the setting, some bad rolls can really set you back; losing a few heroes in one go could be something you’d really struggle to recover from in a campaign. You need heroes to power your warband’s economy through the exploration roll, which is a weird place to be because your heroes are your best warband members and yet you never really want them to get in a fight, if they go out of action, it’ll cost you. Speaking of your warband’s economy, the gold cost for things in this game is so inherently imbalanced I don’t think I’ve seen a single group or event that hasn’t house-ruled some element of it: armour is so expensive for something that’s so easily negated; gunpowder weapons are incredibly underpowered compared to bows and crossbows, especially as no-ones taking armour; the sling and the club, the cheapest items in the game are the best!? BUT. But. But. But. That’s also its charm. If you come into Mordheim expecting a balanced, honed, fair skirmish wargame you’re mistaken. This isn’t a wargame. This is a simulationist game. A narratively designed game. Armour’s expensive because life is cheap in Mordheim. Gunpowder weapons are expensive because they’re statement pieces (look at me, I can afford gunpowder). Clubs and slings are cheap because they would be, and they’re reliable, because historically they always have been. Are these the most fun choices, probably not. But they certainly are the most flavoursome.

All these design choices are intentional, woven throughout the game, immersing you in its world. Because of this, all your dice rolls added together become an emergent narrative. In my first campaign of Mordheim, I was playing Marienburgers (the wealthy Empire faction) and I lost my leader in the second game. This was a pretty big deal. Losing any heroes early on can make progress pretty hard but instead of a series of terrible dice rolls, this instead became part of their story. The story of a warband that were scrabbling around for leadership after the loss of their paymaster and their fight to buy their way back home. After a shaky couple of games, my new leader, a pistol wielding champion named Reinhardt, got a few advances and broke his leg, becoming their no nonsense sergeant firing off orders (and shot) from the rear. Through the next couple of games I got lucky enough to promote a Swordsman (Dieter) and a Marksman (Saskia) to heroes filling up my roster with hard hitting heroes. Slowly what I’d originally thought of as the useless entourage of a spoiled merchant princeling, became the ragged warband of sell-sword mercenaries. I finished off the campaign with their mad dash for the boat they’d hired, whilst their perennial enemy, a hapless vampire named Nash Feratu and his warband of ghouls, dogging their heels.

Of all the narrative games I’ve played, this one felt like one that was trying to generate interesting moments through its design. It wasn’t the loosey goosey vibes based approach of some modern indie skirmish games (which I still rate by the way), and it wasn’t the tacked on narrative approach of modern GW design; competitive ruleset first, narrative as an afterthought. Mordheim is a game of its era, it feels like a game that wants you to piss about and create silly situations, rather than something honed and fully designed. I don’t think it’s perfect by any means, but its vibe is spot on.

Mordheim’s Second Life in Exile

As an “abandoned” game, Mordheim has spent a long time in the wilderness. With no publisher oversight or official miniature production, the entry point to this game has been arcane at best. Not only do you have to find a group of weirdos looking to play a dated Warhammer Fantasy skirmish spin-off you also have to contend with two big hurdles; what are the rules of Mordheim and what miniatures can you play with?

Rules

Now at first these might seem like dumb questions. The rules are in the rulebook. You can download the pdf online. Surely it’s clear? But dear traveller, you would be mistaken. Not only were the original rules in the rulebook out of date in 2004 (with various FAQs correcting the original text, but one another), but you also have a huge variety of ways of running a Mordheim campaign. You can play it straight out the book, rolling scenarios at random for each game or you could have a set scenario each month so you don’t keep playing Skirmish all the time. You could play a Mordheim map campaign, adding in special rules for holding and contesting territory in the city. You can even leave Mordheim entirely and fight for treasure in the foothills of the Empire, the deserts of Khermi or the sweltering jungles of Lustria. Plus there’s loads of additional modules you can add in to the game, from the essential optional crit tables in the back of the rulebook, to Blazing Saddles actually making mounted units fun to play. So you can see, agreeing what the rules actually are can be tricky. Both luckily (or unluckily depending on your perspective) the community have provided some fantastic resources to try and conquer this.

Broheim is a name that should be familiar to anyone in the community, an online resource housing ALL of the content for Mordheim digitally, from the official, to the unofficial, to the fan-created jank. It’s a true testament to the archival skills of Mordheim’s fans. It’s also a right pain in the arse. Because everything is available online it means that establishing rules quorum can be an art, especially when you start to consider house rules. You have to remember that this game started in late 90s/early 00s when fan input, let alone content, had a much higher level of permissibility in the hobby. There’s a long storied history of players looking at some unfun game moments, putting their game design hat on and saying ‘I think I can do this better’, some of which Games Workshop actually published. These changes can be from the minor, from wielding two hand weapons incurring some sort of hit roll penalty, to complete rewrites of the entire game, factions, equipment and all their associated rules. Your view of what counts as ‘good’ Mordheim, could be different to mine. So we’re playing Mordheim? Or did you want to play using Coreheim? Or Wyrdwars? What house rules are we running? Have you thought about undoing the 2002 errata on spears?

This is before you start having to consider which warbands you can even play in a given campaign. Some groups will limit you to only running officially published warbands (Grade 1A), and, with others, it’ll be a free for all or a grab bag of options depending on how overpowered they personally feel each band is. But again that’s part of the fun. Because in a game as old as this, nothing is set in stone. Rules become ruling; community dialogue. Something more malleable and negotiated than a game with hard GT proofed rules. Every campaign organiser I’ve met has always been willing to walk me through their choice of rules, warbands and justify why they think it’s the most fun. It takes a bit of getting used to, but it’s pretty refreshing, if a bit more time consuming to navigate initially. Honestly there’s probably another article right here about this, so look out for that.

Miniatures

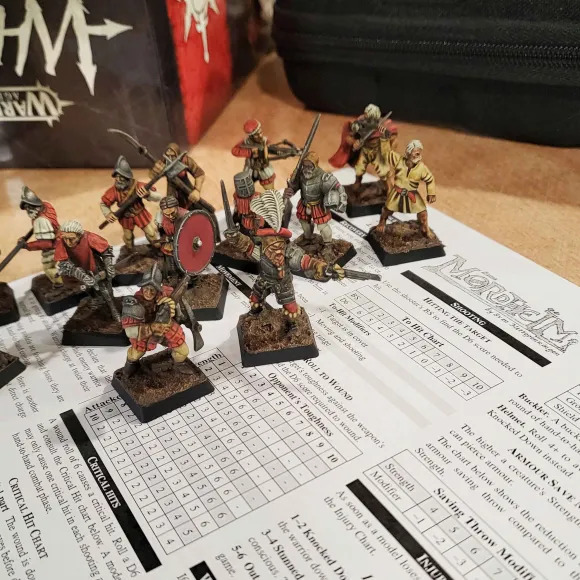

Luckily finding models for the game is the complete opposite. Whilst an original metal Mordheim warband will probably set you back £100+ on eBay no-one in their right mind expects you to play with one. Since its exile from moulds in Nottingham, the community has been forced, nay, has relished an imposed state of requisite creativity. There’s a saying among Necromunda players I know that fits aptly: “Any model is a Necromunda model.” Exactly the same can be said for Mordheim. Trawl through the #mordheim tag even for a second on Instagram and you’ll find a wealth of hugely imaginative conversions. Warcry, Underworlds, Bloodbowl are all obvious places to draw from characterful base models. Age of Sigmar is of course a deep repository, housing the last of the Warhammer Fantasy kits until they’re rotated out, but even then, the latest Cities of Sigmar range added a ton of new weather-beaten humans to base conversion off of. Hell, I’ve even seen some incredible conversions using Warhammer 40,000 models as their base; the dour sisters from Triumph of Saint Katherine becoming the base for an absolutely gorgeous Sisters of Sigmar warband (currently on display at Warhammer World). And now with the Empire range likely returning in plastic for The Old World in the next few months you shouldn’t even feel obliged to convert anything; you’ll basically be using the same kits that were available for players during Mordheim’s actual release.

And that’s not all! Far be it from me to assume you even want to use Games Workshop miniatures. I’ve never met a single player who cared which specific part of Nottingham your miniatures came from so it’s lucky there’s plenty of other fantastic miniature producers that you can use when creating warbands. Frostgrave feels like a game with Mordheim in its DNA, and the plastic kits produced by North Star Figures for both the base game and the Ghost Archipelago setting definitely reflect this, giving you a wide variety of characters and weapon options for any of the Human centric warbands. Oathmark kits, also made by North Star, can easily stand in for some of the Old Worlds fantasy races. Wargames Atlantic also produces one of my favourite kits, Conquistadors, which is an easy stand in for any of the Tilean warbands. This is before I even mention any of the incredible old school design sculpts from companies like Warmonger, Macrocosm and Meridian miniatures.

Also if you’re lucky enough to own the technology of the future and can print your own miniatures (or have a friend who can) well then there’s already a broad range of designers out there producing kits explicitly for Mordheim; Vae Victus, Reptilian Overlord & Punga miniatures to name a few. Don’t even get me started on terrain. For a 25 year old game, there’s never been an easier time to collect it.

Final Thoughts

There’s something heartwarming about how a game can persist beyond the intentions of a publisher. Not because of, nor really in spite of them. Just because people enjoy it. Far removed from any official support, it’s become something that’s owned by its community, boosted and promoted by its biggest fans. It’s a game that feels very much a product of its era, with its commitment to randomness driving narrative, its ‘00s grimdark aesthetic and its single minded swingy game mechanics. It is what it is for better or worse. But I really need to stress that people love this game. Those people, who still post about it, still create beautiful conversions for it, who labour on spectacular terrain boards for it, got me to love it too.

I think you should play Mordheim. I think it still stands up. And honestly it’s never been easier. Come join us. In the City of the Damned!

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.