And farewell to all that MEss.

I’ve now spent some combined 200 hours playing Mass Effect games over the past few months (with a couple rounds of technical difficulties unrelated to the games themselves near the end), so it’s perhaps understandable that I flagged a bit in finishing the fight, as it were, in the trilogy’s final entry. A game very arguably doesn’t need the bloat that Mass Effect 3 has, though for reasons we’ll get to in a bit I’m glad that it had it.

We can start with what’s wrong with Mass Effect 3 on a fundamental level up front, because the game starts with it too. The first clue you’ll get that something is deeply amiss with the final installment of this trilogy is that it begins on Earth, where Shepard has spent an intentionally vague amount of time grounded since the events of the previous game. They do actually tell you how long it is if you go digging or pay attention to off-hand dialogue — it’s six months — but narratively it feels like a couple years. Multiple characters mentioning you languishing in administrative limbo, and having to move on with their lives without you. Six months isn’t that long, Miranda! But again: This is Earth. This is the first time Earth has appeared in a Mass Effect game as a place you visit or interact with (you go to the Moon in the first game, but that’s as close as you get). This isn’t a bait-and-switch either, not of the conventional kind: no matter where else you go in the galaxy, the game is telling you that this story is going to be about Earth.

Another warning sign in this beginning section: Admiral David Anderson, still voiced by the excellent Keith David, spends the entire thirty minute setpiece wherein the Reapers pay off all of Shepard’s warnings and sack the human capital of Vancouver attached fully to Shepard’s hip as the tutorial character. But Anderson is even more than the tutorial character: he is the one giving orders, demanding actions, doing things. Shepard is along for the ride, most notably tied up in the very clumsy symbolism of trying and failing to save a human child from the destruction of the city.

Soon Shepard jets off into space leaving Anderson behind to nobly defend Earth as the head of the Resistance, but throughout the game Anderson looms over the proceedings. Not just through the handwaved ability to have him ring Shepard up on the space phone constantly to check in, which he does — no, returning to Anderson and specifically liberating Earth is the main point of the whole game. Mass Effect 3 is more than happy to conflate this primary narrative arc with what the plot actually demands as Shepard’s main goal — the creation of “the Crucible,” an extremely vague superweapon that will destroy the Reapers in a single blow. This makes absolutely no sense except for all the game’s characters insisting it does, and would work much better if you were given less time to think about it. But this is a 40-60 hour game, depending on what DLC you have installed. You’ll have a lot of time to think about this stuff. And you’ll be doing it while gathering war materiel for Anderson on Earth, running into Anderson’s on-again off-again lover Kahlee Sanders, even fighting a game-long nemesis character who isn’t from Shepard’s past, but from Anderson’s!

When you do reach the endgame and start the long hard slog of tying the game up in a rough knot, it suddenly becomes the David Anderson story again, with the final two hours spent slogging through bombed-out London (looking like a generic war-torn military shooter environment save for the pristine red anachronistic phone booths that have been placed on every other street corner to remind you that this is indeed London) and listening to comms chatter between Anderson and his English and Scottish hard-lad lieutenants as they storm towards certain death. Shepard and company are shoved so hard into the passenger’s seat that in the original release, before the Citadel DLC, the only proper farewell you got to half the important NPCs was ringing them up on the space phone to check in one last time. Shepard’s big motivational speech to the troops even gets preempted by Anderson giving a big motivational speech of his own! And of course, Anderson is there at the end of all things on the Citadel. In a very real sense, David Anderson should have been the protagonist of this video game, if this was the story that BioWare wanted to tell.

The other fifty-five hours or so of play argue that it’s not that story, however. It is the story of the universe-historically special and precious Commander Shepard. As silly as the diegetic awe and splendor for the commander is, by the middle of Mass Effect 3 it’s completely earned, and as this is Shepard’s last ride (hopefully, at least), it’s entirely proper that the game leans into it. The best parts of this game, hands-down and agreed to by all, are when it’s paying off storylines from the first and second titles. Do they connect to the actual story of Mass Effect 3 at all? Nah, not really. In the sumptuous, entirely-too-long cutscene of the assembled war fleet flying into the Reapers surrounding earth, they didn’t even bother modeling in the massive Geth fleet you could add to your forces, because that’s a lot of extra doing when some percentage of players wouldn’t even be saving the Geth. Of course, if stuff like that and the genophage cure on Tuchanka were the actual focus of the huge bombastic cutscenes, this would be less of a problem. As it is, you reconcile a civilization-defining conflict between two species and the only interaction it has with the trials and tribulations of Admiral Anderson is Joker saying “Geth fleet standing by” during roll call.

The genophage and Quarian homeworld content is fantastic, however. The tone of either setpiece can vary wildly based on your choices in the previous game — whether you’re on a collision course with a fantasy world happy ending for the Krogan or whether the Krogan have once again been played for suckers by the Council races depends mostly on whether you saved Maelon’s data from the previous title. It doesn’t really matter for the outcome of this game which you picked; you’ll get the War Score Points to fill up your War Score Meter regardless of whether the genophage is cured or not, with slightly different distributions that are almost entirely cosmetic; nothing about this game’s ending “matters.” The same is broadly true for the resolution of the quarian war with the geth, which similarly loses any pretense of ambiguity over what kind of story is being told but can still end up with a bunch of different tone notes depending on how you prefer your Mass Effect 3 to taste. Either way, Mordin Solus and Legion are dying, though. You can’t have spooky dreams haunted by the voices of the dead if it’s possible to get there with only whoever you left behind on Virmire way back in the first game weighing on your conscience.

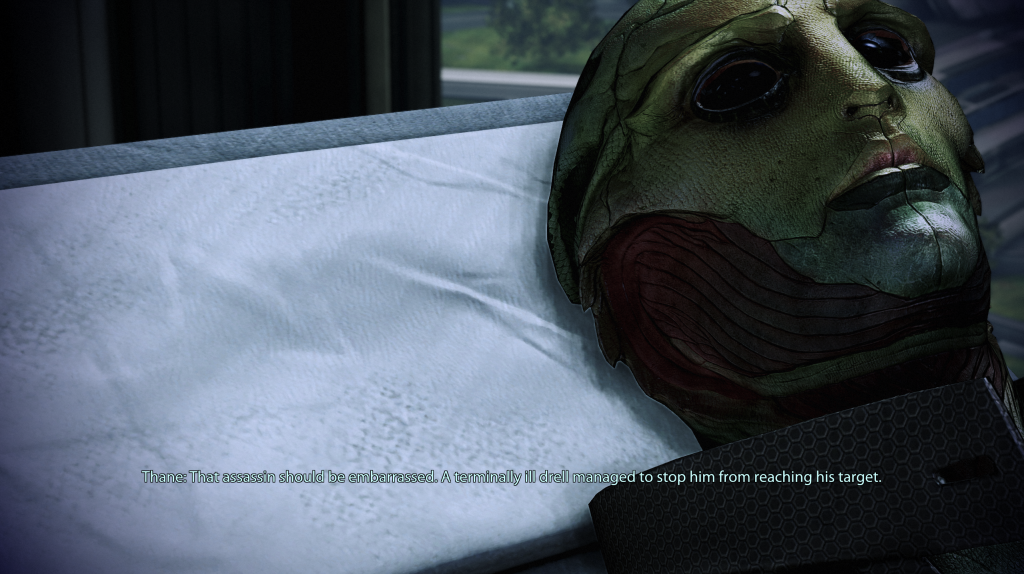

One of the genuinely commendable things about Mass Effect 3’s writing is how comfortable it is with you not making the perfect plays in these situations, even if you’ve imported a file that’s made all the right moves up to this choice. If you want to fuck over the Krogans, you can do that! If you want to genocide the Geth, or even completely screw over both sides in the Quarian/Geth war, you can do that too! You’ll get a lot of sad piano scenes, a lot of characters dying when they otherwise wouldn’t have, and if you do it too much, you’ll put one of the endings (the Destruction ending where Shepard lives) completely out of reach, but frankly who cares about those. There’s enough War Score hidden away in the planets of the Milky Way galaxy to tolerate a lot of Shepard fucking around and ruining things. Now, it takes a certain type of personality to get through two games and then want to ruin things on purpose just to see what it looks like — just like it takes a certain type of person to, say, want to play through the Caesar’s Legion plotline in Fallout: New Vegas. But it’s good that, for those specific few, this sort of content exists. Eight playthroughs in, though, I still haven’t seen, e.g., the version of the cinematic on the Citadel where Kai Leng kills Miranda instead of Thane (because Thane’s already dead) or, if both are dead, Captain Kirrahe eats it. There’s just too much investment in the previous games for me to try for anything less than the best ending for my Shepard by the time I hit the third title.

Kai Leng, though. Kai Leng. Someone in this game’s development — I’m betting it’s Mac Walters, the lead writer of Mass Effect 3 who also had his hands in a bunch of other Mass Effect 3-adjacent comics and media starring David Anderson and Kai Leng, but it doesn’t really matter who — really thought they had something on their hands with Kai Leng. And you get the impression that the rest of the writer’s room did their best to sand down, undercut, or otherwise avoid this guy, but he is what he is. And what he is, is a Space Ninja who spends a lot of his time showing off in cutscenes, winning fights in cutscenes, and scarpering off in cutscenes before Shepard can do much of anything about it.

I’m ambivalent about whether Kai Leng could have ever really worked. It’s a big problem, for instance, that this is his first appearance in the series (as mentioned before, he’s from Admiral Anderson’s backstory, not Shepard’s). There’s a simpler and plainly obvious person who should be in this role of cyborg reconstructed supersoldier hunting down Shepard with a vengeance: whoever it was that Shepard left to die on Virmire. The voice actors for Ashley and Kaiden were already doing full companion work for their characters; they were already going to be spending a lot of time in-studio. But this would conflict with the spooky dream mandate above and, arguably, cheapen the sacrifice the character made in the first game (my argument is that once BioWare opened the resurrection box with Shepard themselves in Mass Effect 2, the sacrosanctity argument went all the way off the table).

Even if it was Kaiden or Ashley in that role instead, though, the bigger problem is that this guy’s whole character arc is running around the galaxy, bragging and trolling you, while Anderson and everyone else send you emails going “Whoa, Shepard; this is one of the real old tough guys. Look out!” Anyone familiar with professional wrestling knows the concept of heel heat — it’s what the bad guys build as they kick the good guys in the nuts, hit them with chairs while the ref isn’t watching, and otherwise cheat. When a heel is building heat the correct way — arguably the way Saren did in Mass Effect, though he was a bit of an absentee villain for the middle of that game — you want to keep going to see the guy get his come-uppance. When he’s doing it wrong, though, you tune out, drop off, and stop paying attention to that storyline. Kai Leng pretty much exclusively builds bad heat. It’s not as a bad as a lot of people remember it, mainly because there’s so much less Kai Leng once you’re playing with the Leviathan, Omega, and Citadel DLCs installed, but there is an embarrassing tone-deafness to his whole deal given how this series plays with cutscenes in Mass Effect 2 and in every part of Mass Effect 3 that doesn’t involve Kai Leng: I’m fairly certain you never get a paragon or renegade interrupt in any of his cutscenes until you’ve beaten his bossfight at the Cerberus base, which is when you finally get the prompt to kill him. Shepard being able to assert their protagonism and alter the flow of scripted events is a huge part of their whole ‘deal’ in the second and third games, and would have been in the first too if they’d thought of it then. If you’re going to remove that and have Shepard caught flatfooted and bumbling in every encounter with this guy, and indeed give him the interrupts for stuff like killing Thane, then you better bring something to the table more compelling than Troy Baker doing his least impressive scary voice for a space ninja.

As mentioned, though, you spend relatively less time graced by Kai Leng’s presence the more DLC you have installed, and the three main DLC modules are all absolutely worth your time. There is also the “DLC party member” — Javik, the racist Prothean, who is essentially an extended joke about the hubris of paleoanthropology told at poor Dr. Tsoni’s expense — but he is a portent of bad content trends to come: he was clearly cut from the main game and gated behind a DLC paywall, and indeed, when you originally bought Mass Effect 3 on release in 2013, the “download” for Javik was some trivially small file, less than a megabyte, because all of Javik’s data was already on the disk itself. Frankly, though, Javik should never have been in the game to begin with. The longform joke he represents pales in comparison to the opportunity cost of putting him in instead of, say, a Krogan (this game has no Krogan companion!) or even more obviously, a Batarian. This was the moment for the Batarians, brutally done wrong by in the Arrival DLC and in the opening phase of the Reaper invasion, to finally get a humanizing NPC that challenged Shepard’s preconceptions about their species while serving with distinction. Nope! Instead there’s this weird asshole exploring conceptual space that Mass Effect 2 already neatly tied off. Leviathan, Omega, and Citadel, however, are much more substantial investments, each adding at least three hours of play time to the game depending on what difficulty you’ve set it to, and Citadel especially adding three hours or so of just fanservice scene content of Shepard hanging out with their friends after the main meat of the DLC has concluded.

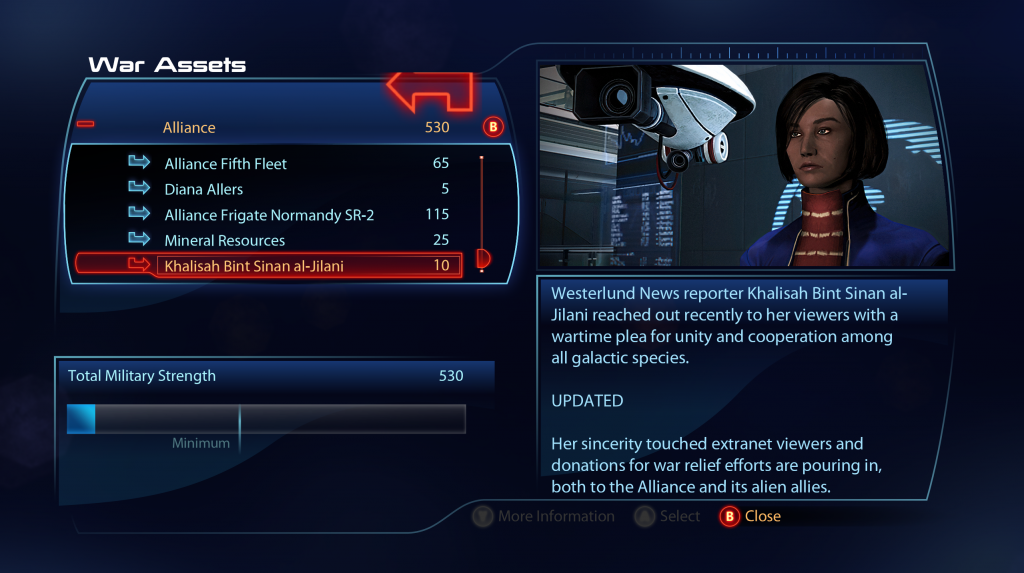

The main thing missing from Mass Effect 3 in the Legendary Edition is the multiplayer component, which is either a relief or a source of grumbling depending who you are. In the original release, a full half of the War Score rating your Shepard was trying to build in the main game was based on how you were engaging with the multiplayer — an extremely brute force and frankly unwelcome mechanism to make people who came to this series for a single player experience engage with a proto-live service implementation. If you’re wondering why that choice was made, please remember that BioWare is an Electronic Arts brand. Either way, that got changed when BioWare released the free ending DLC patch as part of their attempt to manage the nightmare PR that accompanied this game’s release, and despite some talk about rebalancing it a third time it’s basically in the same place they ended up before: if you do all the missions, and are good about carrying over your side quests from previous games, you’ll have no problem filling up that bar. And if you missed a few things, well. It’s a big galaxy; go scan some planets. I had a full bar around the time I was beginning the missions on the Quarian homeworld, and my Shepard started deeper in the hole than others might by sacrificing the Alliance fleet to save the Council in Mass Effect and just, not doing the Arrival DLC at the end of Mass Effect 2 (which gets a bunch of human marines killed instead). For the relatively few but very vocal fans of the original release’s multiplayer, well, you can never go home again. You probably didn’t want to see what 2021 Electronic Arts would have done to it anyway.

Which brings us to the end of the game, and the end of Commander Shepard. Good lord, what a fumble. The game rushes to actually figure out a way to join the “build the superweapon to defeat the Reapers” plot with the “save Earth” plot, and its answer is to, offscreen, have the Citadel move halfway across the galaxy to Earth for arbitrary reasons (“so the Reapers can better defend it”) because the Citadel is, once-again, the twist-ending maguffin you’ve been chasing this entire game — “the Crucible” requires something called “the Catalyst,” and you discover in hour 58 of 60 that this Catalyst is the Citadel itself. All of this is narrated to you by a Prothean VI in a haphazard callback to Vigil on Ilos, but unlike Vigil, this guy simply forgets the pretense of being an ancient echo of a dead race and just directly spoon feeds you narration of events that would take a lot more time to actually animate, or have Shepard involved in. Much better to just move all the pieces where they need to be on the chessboard by narrative fiat.

Once you get through London, it’s just you and Anderson on the Citadel with the Illusive Man. There’s a much better version of this story where Cerberus and the Illusive Man generally stay onside and allied with Commander Shepard while it’s Admiral Hackett, Admiral Anderson, and the Alliance that fall to Reaper indoctrination and the plot of the game is making war against an indoctrinated Earth being turned into a planet-sized Reaper, but I understand why they did it this way: when you have Martin Sheen on retainer, you give Martin Sheen the big villain speech. That’s simply the best use of talent. The much bigger strike against this final confrontation is that it is done…with Commander Shepard…limping…through…the Citadel…as slow as they can possibly go. I didn’t even like this when Kojima and company did it in Metal Gear Solid 4, but at least they did something with it! They really put Snake through the wringer! It’s only two or three minutes of stumbling, but when you’re this close to finally hammering in that last nail, even that’s too long.

The resolution of the Illusive Man’s plot is fine, I suppose. It doesn’t break the top three of “convincing CRPG villains to kill themselves,” and doesn’t even surpass Saren’s attempt back in Mass Effect, to which it is an obvious callback. The real bullshit starts flowing when you head upstairs to talk to the Reaper subroutine wearing the face of the child you’ve been dreaming about all game. By now it’s almost folklore what happens: he gives you a speech about how all of this was his plan all along to get you here, to this moment, to decide the fate of the galaxy. Do you want the red ending, the blue ending, or the green ending?

A common complaint is that these endings were all “the same,” and in the original version of the game there was a lot to this — but it’s worth acknowledging some of the differences in order to complain about them. Did you know the Illusive Man was completely and totally correct in every particular? That the Reapers could be harnessed for the good of the galaxy, or humanity, or whoever the intelligence commanding them wished? That the only thing he was wrong about is thinking that he could do it himself, instead of you, Commander Shepard, the sainted hand of galactic destiny? That’s the Control ending, and it’s the ending we never pick in this household.

The Destruction ending is the ending I choose for my renegade Shepards who care less about the future of the galaxy than they do about their friends and found family aboard the Normandy; after all, it’s the only ending where Shepard can survive if you do everything right. For this playthrough I chose Synthesis, the “good” ending, which is goofy as hell: all life in the galaxy becomes an organic-synthetic hybrid, ending all war and creating a mass, shared gestalt consciousness that leads the Milky Way galaxy into a golden age, and possibly defeats death itself. The tradeoff is that everyone gets these incredibly silly circuit board meshes applied to them, and glowing green eyes. Small price to pay for complete galactic harmony, I say. The endings still feel unfulfilling even in the expanded ending DLC — they didn’t go through and give a little clip about where every NPC ended up, which they absolutely should have done; it’s a lot of work, but it is absolutely necessary work to tie a project of this size off — but I have to say I appreciate boldly changing the universal status quo so irrevocably as to foreclose the possibility of sequels. BioWare is obviously regretting this now, of course; I hope they don’t renege on the audacity of the endings’ scope and effectively say, “Well, you want Shepard back, and we can’t figure out how to tell stories without Shepard and the gang, so we’re going to cheapen everything we did here and give you some more slop.” Because the fans are gonna realize very quickly that what they said they wanted was not what they actually wanted.

All in all, I liked my time with Mass Effect 3 more than I was expecting this time around, both due to Legendary Edition improvements (thanks to bug fixes, this was my first time actually seeing the conclusion to Conrad Verner’s story, which was weirdly silly) and because I’ve mellowed on some of its worse aspects the further we’ve gotten away from release. Most people buying this edition will not be coming to these games for the first time; to them, I say, yeah, a lot of this game still sucks. The bare skeleton of it? Pretty bad. But with all the DLC and with wounds that have healed over the last eight years, I think you’ll get a lot more out of this game the second (or third, or fifth, whatever) time around.

At least until it’s time to go to London.

Final Verdict:

Glad I bought it, glad I played it, glad I reviewed it. One of the best products EA has put out in years. Alright, that might be an extremely backhanded compliment, but it’s still good.

Have any questions or feedback? Want to share your experiences piloting the Normandy? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.