This is part 9 in Lenoon’s ongoing series. If you missed the others, you can find them here

I am not, unfortunately, a tactical and strategic genius when it comes to actually playing historicals. I lose, a lot, at Sharp Practice. I have never won a game of Pike and Shotte. I won, once, playing Black Powder with a mate’s army. The last time I played Blucher, solo on my kitchen table, I managed to simultaneously rout both armies – I lost, against myself. Some of that is because I’m just straight up bad at games – I like to make and paint and chuck dice while someone else points out rule interactions I have forgotten. On the page, I can understand rules and analyse them. On the table, it’s all about making cool explosion noises and horse whinnying.

The other half of it though is that I’m not thinking Napoleon enough. Napoleon was, above all else, an artilleryman, and I have no guns in my Guard. I have enough infantry that painting them is now a massive chore, and will only include one more unit at most, cavalry is certainly getting there, but I don’t have a single gun. Well, now I have a gun. So now, surely, I’ll start to win games?

Real cannon to the Right of Them

Like everything else in Napoleonics, the artillery is initially complex but once you dive into it, really interesting. Napoleon used artillery like noone ever had before – massed batteries, advancing to close range or sprinting to enfilade, aggressive deployment and audacious, devastating bombardments. He could do that largely due to the theoretical and practical advances of the French artillery above and beyond the other European nations. Mid 18th century artillery was often slow, dragged around by ropes and oxen driven by civilians, occasionally scattered around the infantry or used for long range counterbattery operations. Prerevolutionary officer Jean-Baptiste Gribeauval had the very simple in retrospect idea: artillery should be standardised, mobile and professionalised. It was a pretty controversial idea, but by 1776, he had an iron grip on French artillery and put his ideas into practice.

Napoleon grew up under the Gribeauval system, and cut his teeth as an artillery officer, putting the Gribeauval principles into great effect at the Siege of Toulon where he won his first, enduring fame. Napoleon learnt that guns, massed and deployed effectively, weren’t just a way of grinding down enemy positions, but would break a division, an army, a city, a revolution – an empire. His experience, and relentless micromanagement refined the Gribeauval system into the System of Year XI, honing the French artillery into a stripped down, honed scalpel. Standardised, lighter and professionalised artillery could be wielded like infantry and cavalry, and didn’t he just do it – at Wagram he put the Guard artillery within musket range of the Austrian line, and simply said “Erase the masses” (they did). The Guard artillery held the line to the last when Paris fell in 1814, the gun barrels glowing hot on La Villette before they threw them in the canal pretty much exactly where I stopped for a beer and pizza on my trip to Paris in May.

In the games I play, particularly in Sharp Practice, guns are brought up close and used in the classic Napoleonic style. The first time I put my Grenadiers a cheval on the table, a British gun wiped them off the board with a single shot. I’m always pinned down, unable to exert pressure where I need it. That changes today.

Mini cannon to the Left of Them

Guard artillery, like everything else to do with the Guard, is a complex beast. Artillerymen were recruited into the Guard from line artillery, the decree of 1802 asking for two of the best, tallest, most well behaved, men from each regiment and massing them (1813 numbers) into 40 Gun Old Guard and 32 Gun Young Guard regiments. In typical style, they were paid more than line gunners, treated better, fervently loved Napoleon and then, of course, nearly all died in Russia. As my army is set in 1813, it’s rapidly recovering (to a dubious extent) after the disaster in Russia. The Guard Artillery was reconstituted quicker than most other Guard formations, with soldiers drawn from Spain and Central European deployments, and the standardisation of the Year XI system meant that replacing the lost guns was astonishingly quick.

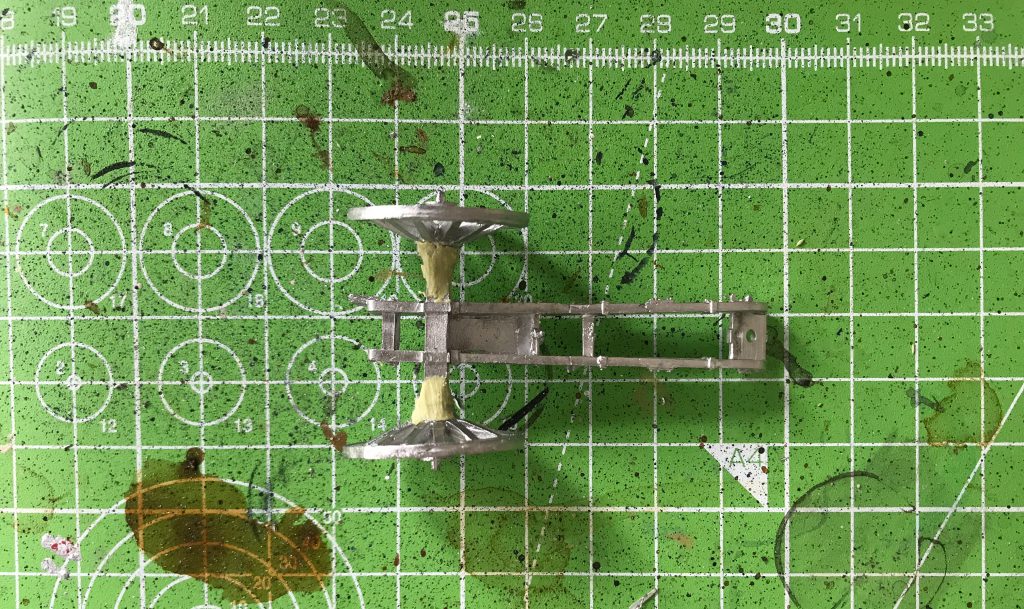

As I’ve overwhelmed my Old Guard with Young and Middle recently, I’ve gone for the Old Guard Artillery – Napoleon’s favourite sons, wielding a 12 pounder, Napoleon’s “cherished Daughters”. I’ve not made a big metal model for a while, so I broke down the assembly and painting into a couple of stages. All artillery models are small dioramas in and of themselves, so it was a much more careful process than most of my Imperial Guard. After cleaning off flash and (most) of the mould lines, I carefully pinned the wheels and reinforced the join to the carriage with some modelling clay. I’ve not done a clean job of it, but luckily this will be invisible on the finished model.

This model is Guard loading the gun, so there’s distinct roles for each of the four gunners in the kit. There’s a man bringing up the shot and powder package, the gunner standing by with the linstock to light the gun, one stabilising the carriage and, finally, a man with a combination sponge/rammer to secure the ball and powder. They’re all at the usual high Perry standard, bags of character and in campaign uniform, fitting in with all my other Guard.

I want to arrange my gun slightly differently to keep it on a slightly smaller base than needed by having the full length of rammer/sponge. Instead, I’m going to have my gunner sponging out the barrel, by cutting off the sponge end and affixing it to the gun barrel. Before doing that, I’ve spaced out everything as I want, added base material, painted the underside of the carriage black and secured the gun to the base with a little more modelling putty.

Once everything was dry, I drilled a hole into the barrel large enough to fit the sponge stick into, and undercoated everything before painting. I painted these in the usual way – using the always excellent Napoleon, his armies and his enemies as a reference. The gun was in some ways the trickiest part – it would need to hold up to scrutiny but also to me repeatedly touching it during painting, bashing the carriage and barrel around when I’m trying to fiddle about with the crew and needed to be painted first before the men get in the way. There’s also a lot of confusing info about what to paint your guns – they were cast bronze and occasionally cast iron with wrought iron fixings, but there’s images of them with a black coat, a shiny bronze finish, a more coppery bronze finish and a highly polished silver. In keeping with my slightly grubby Guard, I’ve gone with a black finish, which could be covering a nice bronze cannon…. yeah let’s go with that. On this one I fully expect to be corrected in the comments (and will appreciate the clarification!).

I think it’s come out pretty well, and keeping it on a smaller base means I could use a second small base to represent the additional men, or horses, used to move the gun around if I’m playing on a larger table. With one gun done, more will follow – now I’ve got the knack of it, another two 12lb teams will make for a nice mini-battery, and then horse artillery to accompany my growing cavalry wing will eventually arrive.

Volleying and Thundering

The first time this cannon hit the board was just last week – running a demo game (I’ve never run a demo game before) for Soldiers of Napoleon. It was also the first time the entire army so far has been deployed at once, points be damned and bayonets out. I set this up as a fairly simple line versus line, to run a good intro to the ruleset and to give some new people a brutal clash of an intro to Napoleonics.

It went well, with cautious and cagy play sheltering infantry from the worst of the storm of shot and shell flung around by the cannon on both sides, until a crashing cavalry charge led to a swirling hellish melee and multiple broken units on both sides. With the British centre broken, but the Guard falling back in disarray, we ended on a strong Eylau note – nothing conclusive, but a lot of terrible losses. I learnt a lot about running a demo game – mainly things not to do next time – and am going to be running more in the future!

Stormed with Shot and Shell

With the Guard Artillery firmly in focus this month, the badass of the week goes to General Antoine Drouot, the “sage of the Grande Armee”. A truly severe, hard man, who went into battle with a bible and a sword, Drouot commanded from the centre of the artillery park, very much on the front line. There’s a lot of stories about him that make him sound like someone you wouldn’t want to be around – severe, strict, fanatical and dour – but the astonishing thing is that he fought in the Army of the Rhine, of Naples, the Grand Armee, went to Russia, fought at Leipzig and Waterloo Trafalgar – making him the only officer who fought in the three battles that sealed Napoleon’s fate. Oh, and he was on Elba as well. If there’s someone who you could legitimately write Sharp-style “went everywhere” novels about, it’s Drouot, and that’s pretty cool.

On the most complex front of the war – the front where I read stuff – I’ve been reading more about Haiti. Avengers of the New World by Laurent Dubois is good, broadening out my very Toussaint focused research on Haiti, but didn’t add much to Black Spartacus, which remains the top recommendation from me on the conflict. The recommendation this week is Tropics of Haiti, Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution by Marlene Daut, which though I’m only about 25% of the way through is a really fascinating discussion of the legacy, historiography and ownership of the Haitian revolution. I’m learning a lot – and questioning a lot about what I’m doing as a white guy on the internet making tiny revolutionaries.

Next time: Battle-ready

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.