It is Tridi, Decade 3, Vendemiaire, CCXXXI, the day of the Turnip. It has been two full months since I last wrote a Road to Austerlitz, and, for various reasons, the least productive I have been on this Napoleonics journey in the 10 months since I started it. There’s good reasons for that, and less good reasons, but the best reason is that finally, almost, the heavens open and the blessings of Napoleon and Louverture rain down upon me: I have a full army for 28mm games.

This is part 10 in Lenoon’s ongoing series. If you missed the others, you can find them here

There’s still some work to do, still lots of reading to be done, still Napoleon himself to purchase and paint and notably lots of terrain to make, but as far as the army itself goes? We’re ready. We’re done. We’re mustered for Austerlitz, and it feels encroyable.

Raising an Army

It’s an interesting concept, being “done”. On the tabletop it’s pretty clear, you have your points limit (for me usually “what I could get painted in time”), and some bits and pieces – deployment points, objectives, markers, tracking counters etc – and your rules. I’ve got all of that, and – more or less – did it without suffering hobby burnout, by scraping up units from all over the place and generally mixing and matching kits as I’ve found them. As I’ve read more, it’s turned out that this is exactly what Napoleon had to do in 1813 – giving me the slightly eerie sense that it wasn’t me who planned this out at all.

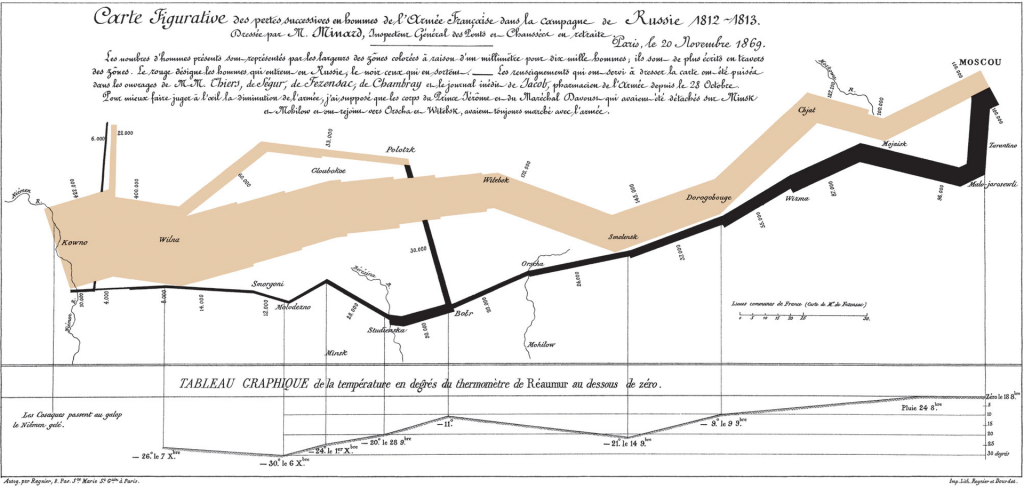

I’ve alluded to it before, but 1813 was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars – one that was both a testament to Napoleon’s hubris but also his incredible organisational skill. When the Grand Armee crossed over into Russia in 1812, it was the largest army Europe had ever seen. Perhaps upwards of 600,000 soldiers crossed the Niemen – as few as 40,000 returned. While that included vast numbers of Allied troops, the Grand Armee suffered badly – Minard’s famous map has only 10,000 getting back into what was nominally “friendly” territory. When Napoleon left the Grand Armee behind to freeze, he knew that his only hope was to return, rearm and prepare for the fights ahead. Suddenly, the world-conquering Grand Armee, the invincible aura of Napoleon and his army was shattered – formerly subjugated and allied nations slipped out from under the French boot, and the War of the Sixth Coalition began.

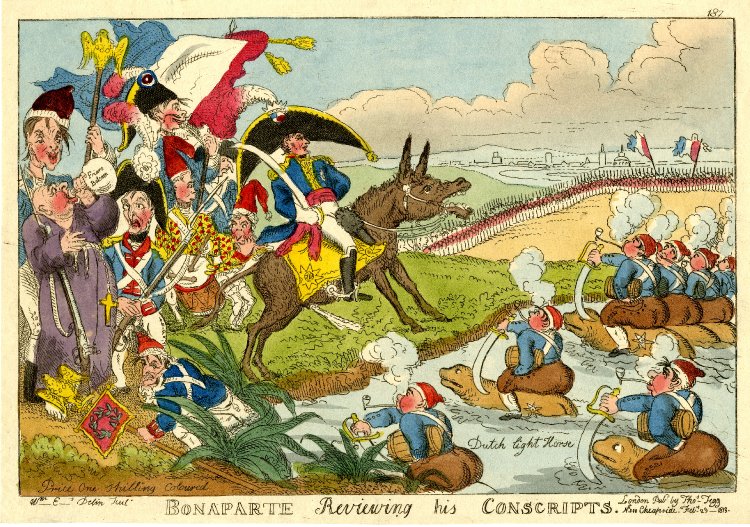

That’s where my troops come in – between December 1812 and March 1813 Napoleon managed to scrape together another army of 500,000 men. Massive troop buildups, recalling men from Spain, from defensive postings throughout the Empire, calling up classes of conscripts, every single way Napoleon could get men armed and trained was used. By April, the Imperial Guard was the largest single contingent of the Army. Early battles turned new recruits into hardened veterans – Lutzen and Bautzen – but bled the new Grand Armee. After a brief armistice, the Guard were the lynchpin of Napoleon’s strategy at the Battle of Leipzig – the largest battle in European history before the carnage of the First World War.

Thrown back at Leipzig, Napoleon retreated to France to build yet another army. Now, the Guard was no longer the final reserve, but the hammer and the anvil. The Young Guard – now brutally young – were thrown into vicious combat as the first line of defence, Napoleon himself wielding desperately raised units into the face of the advancing Coalition generals.

Those two armies raised between Russia and Abdication were drawn from everywhere, equipped with everything and in a mix of uniform styles, ages and pieces. Whatever could march, shoot and hold the line was used. I’ve done exactly the same thing, arriving at a hodgepodge 28mm rushed to fight a big battle coming up soon (you’ll have to wait till next time to hear about it!).

A Desperate Draft

Aside from one unit which will feature another time, the 28mm soldiers are now finished and ready for the field. This mainly involved upping the numbers in both infantry and cavalry to turn some under-strength units into full battalions and squadrons. I think it’s probably something that most historicals gamers have run into – there is, eventually, a certain monotony to getting all of your units up to “full” strength. I decided way back in Part 3 that the basic battalion unit was 22 models strong – three six man bases and two of two, and my final unit of Middle Guard has been sat at 10 men for far too long. My eight-horse squadrons look great on their big bases, but turning them to 10 men would at least let me distinguish visually (if unevenly) between line and column. The horses were not so bad – I picked up a single Perry Dragoon (sold by the sprue!) to add to my Victrix dragoons, and used the spare Cuirassiers, and they’re totally done, hurrah! I’m really happy with both squadrons, and feel that I’ve more or less conquered my abiding fear of horses.

The Infantry though, I’ve been looking at now for four months. Basecoated, stuck to a multibase and then left under my monitor. I often find the the final models in a squad are immensely difficult to finish off. When drafting this out I wrote about desertion in the Napoleonic period but I think it’s probably better to be kinder to myself here. Like I’m sure a lot of other hobbyists with attention disorders do, I will let those final unpainted models hang over me until they cause burnout and recriminations and loom large on my painting queue. So instead I said fuck it this week, and I advise you to do the same. Be kind to yourself. Why paint something you can’t be bothered to? My army is set in 1813. If one battalion is under strength, it’s all the more accurate. I was thinking of these as a second unit of Turin Velites, but, with a slight change to the NCO flag and the addition of a sapper, we have their equivalents from Florence to join the regimental command cadre – hence the red epaulettes, which was totally not because I forgot they should all be white!

The Florence Velites were (just like the Turin ones) an Italian regiment raised in 1809 at least partially to make money and partially to bind the middle class of the recently annexed northern Italy to the French Empire. Raising a unit into the Guard was also a (weird) gesture of brotherly love – for Elisa Bonaparte, Grand Duchess of Tuscany. Another unit slightly off to one side of the main Guard force, they were ranked as Middle Guard. There’s a lot about them possibly being more “ceremonial” or court based, but they were accepting new recruits in 1813 in depots in Germany and fought at Leipzig, so they definitely saw some serious action. By 1813 they were one of the smaller units in the guard, as discontent with the Empire simmered in Italy – perfect as a 16 man command then!

While writing this as well, I ended up grabbing 6 more single-piece plastic line out of the to build pile, then slapped some green paint on them to bolster my Flanquers-Chasseurs to a 12 man squad. Choosing to leave off the backpacks to show them as quickly-kitted out as possible really sped things up here, and I enjoyed them enough to probably add another 12 in the future, all on single bases for easy play in Sharp Practice. The glorious pressure of a Goonhammer deadline!

The Guard March to the Sound of the Guns

You might have noticed I like a theme, and a narrative – my deployment points show it and if I’ve got a full army now, I need objective markers for them to fight over. Seize the ford, take the road, defend the rearguard, all that jazz, but supporting myself to remember that objectives are a thing and games usually run on them by adding some miniatures to the collection that let me visualise them. If the Guard were anything, they were a reserve, cast in at the key moment to deliver the Emperor’s will at the point of a bayonet. Even in the dark days leading to the defence of Paris, the Guard were there, sprinting from battlefield to battlefield until the treachery of the marshals broke the empire.

I got a bit lost in the image there, but the main thing was objectives, right? What objective markers could the Guard march to if not places where the infantry of the Ligne have tried, and fallen? Casualty models from Perry and Front Rank make for excellent objective markers. Here, a fallen Line infantryman shows where the enemy were driven back, and a tenuous foothold must be reinforced. There, the shattered remains of a battalion cluster around a bridge that must be stormed.

Casualties as objectives immediately situates my guard where they should be – embedded in a larger, ongoing action. It immediately and very visually tells the tale of a reserve marching to save the day – as at Borodino, or Jena, or Hanau or Bar sur-Aube, or any number of other times and shattered fields of battle where the cry went up “La Garde! La Garde!”

The Future is a matter of Contempt

So, where do I go now – and where is this series going now? Well, there’s still a few 28mm units to do, even if I consider the army “done” at this stage. I want to model the Chasseurs a Cheval, expand the Flanquers, get two more guns, and, most excitingly, make a unit of Eclaireurs, Napoleon’s experimental answer to the Cossacks. These don’t have a kit, and illustrations are few and varying, so that might be quite an involved project.

More importantly, there’s 6mm, and more 3mm (maybe), and terrain to do for both, and maybe some ships, some spooky takes on Napoleonics and some skirmish forces for small scale games. That will comfortably hit the 1,000 men mark. On top of everything though, there’s games to play. Lots, and lots, of games to play. I might even get good at them – but there’s no guarantee there.

Show me a family of Readers

Reading and Badasses usually go together, and my book this month(s) has been The Fall of Robespierre, 24 hours in Revolutionary Paris by Colin Jones. I haven’t read such a detailed and meticulous micro-history for a long while, and I thoroughly enjoyed this one. You’ll need at least a fair grasp of the French Revolution to really enjoy it, but if you have that already you’ll really like it. Drilling in to the actions of key players and ordinary Parisians to such a level of granular detail is fantastic, and it’s paced like a series of 24 – mostly fast, with some red herring asides.

The Badass then could be Robespierre, but that’s probably too easy. Out of the shadows of the book comes the technocrat supreme Lazare Carnot, the “Organiser of Victory”. Carnot is very much a disaster movie stereotype, one of the relatively few times in human history when an administrator, mathematician and physicist actually does save the day by doing some extreme beautiful mind style thinking. Jones’ book sent me down the rabbithole of Carnot’s contributions to revolutionary France – organising the levee en masse to build the army, mixing conscripts and volunteers and veterans, passing laws to seize church property to turn it into cannon. But the coolest thing is his contribution to the Battle of Wattignies, when the revolution was saved by the heroism of the conscript and – supposedly – the direct battlefield leadership of Carnot. Except it wasn’t, it was all on General Jourdan, but Carnot, as representative on mission for the Committee of Public Safety, could simply write that he was responsible. For one reason or another, the news is filled with conniving bastards at the moment, so Carnot gets the badass award for simply changing history until he won. It’s certainly one way to do it.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.