In the ever-expanding world of RPGs, it can be hard to find a new system that doesn’t feel like an offshoot of D&D or Powered by the Apocalypse—at least not a system that feels playable. That’s not for nothing; both those games have shown fantastic staying power in the gaming world and can do great things.

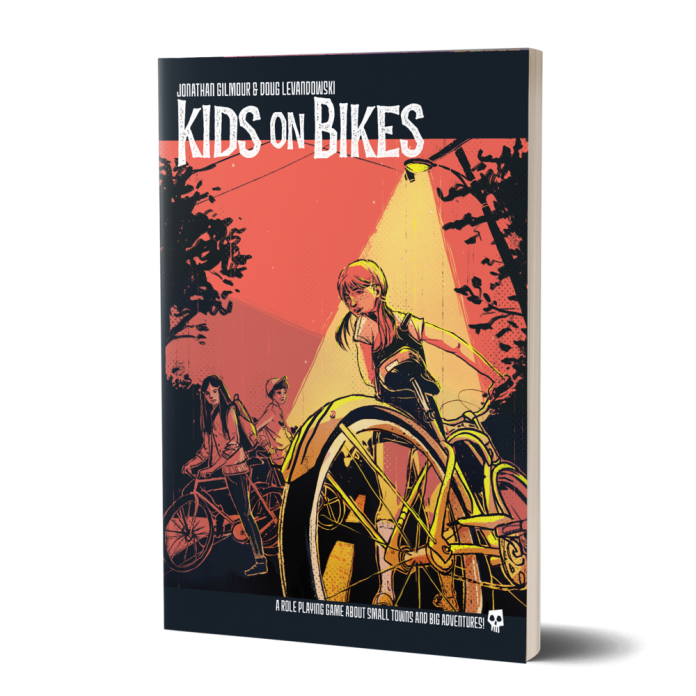

The Kids on Bikes system, published by Renegade Game Studios, is an exception. It is one of the first games I immediately noticed as having a different structure. While it still uses enough of the same “language” for experienced players to transfer over, it’s straightforward enough for new players to understand.

If anything, the game suffers from detailed explanation in the wrong areas while leaving some confusing bits alone. Perhaps this has to do more with book writing than the game itself.

Kids on Bikes, loosely based on Stranger Things and other stories where a group of kids discover something awesome, was the original sourcebook for the system. I personally haven’t played the O.G. since my table wasn’t as interested in that story. Rather, I’ve played the later re-flavorings of the system.

Kids on Brooms tackles the magical school genre, full of clear references to the Harry Potter series. Most of those references come with a note of derision, but I’ll get more into that later.

Teens in Space is slightly harder to pin, genre-wise. The text refers to space opera, but the idea of a “teen” seems to throw a wrench in that [Ed. Zenon fans rejoice].

I’m mainly here to talk about the system, though, so let’s start there.

The System

It feels as if authors Jonathan Gilmour and Doug Levandowski sat down with the mission of creating a system which could use a full set of six role-playing dice. Against all odds, they did it. You’ll actually use that D12 every session.

Each character has six stats: Brains, Brawn, Fight, Flight, Charm and Grit. (They’re almost equivalent to D&D stats, but not quite.)

Each character uses a different die for each stat, with the larger dice correlating to their stronger abilities.

A stereotypical meathead warrior might have a D20 for Brawn, a D12 for Fight, a D10 for Grit, a D8 for Flight, a D6 for Charm and a D4 for Brains. On the other hand, a suave and quick-thinking character might have a D20 for Charm, a D12 for Brains, a D10 for Flight, a D8 for Grit, a D6 for Fight and a D4 for Brawn.

The array of stats easily reveals strengths and weaknesses in a character because you’re basically forced to min-max. This can be offset or enhanced during character creation as you’ll be able to add a few bonuses to various abilities, just to avoid complete failures in certain areas.

It’s kind of crazy that this use of dice doesn’t exist elsewhere. Using different dice for different every different stat feels entirely obvious once you think of it and the rest of the rules balance it out pretty well.

There are no specific actions written out in the system. Instead, players say what they would like to do and the GM sets the number they must beat and what stat should be used. Success and failure scale on how far away the number rolled is from what it needed to be.

If a character has a high enough die for a specific skill and enough time to have planned out their action, the player can choose to take half the number on the die. For example, a smart character with a D20 for Brains who has plenty of time to read and study before writing an essay could go ahead and claim a 10 for the check to write that essay without rolling. This way they won’t keep failing what’s meant to be their main skill.

Success is also far more difficult depending on the die correlating to the required stat. It’s never impossible, though: if you roll the highest number on the die, you get to reroll and add the numbers together. That can continue to stack infinitely.

This is especially cool because the lower the number of sides, the higher the chance you have of hitting that high number. The system is practically built for characters to overcome all odds, pushing past their weaknesses in big plot moments.

Players also “fail upward” by receiving one “Adversity Token” for each failed check which can be exchanged, one-for-one, to add to rolls.

Instead of classes, the books offer “Tropes,” much like the ones I used to explain the stats. They also come accompanied with a few character-building questions to jumpstart backstory writing and choose strengths and flaws.

Characters also have Strengths and Flaws. Strengths have mechanical implications. Choosing a strength off of the offered lists gives you a specific ability or a bonus to a stat. You can choose Strengths based on the type of character you want to roleplay, or based on the ability you want.

Other parts of the system change from book to book in order to fit the genre. Flaws have mechanical implications in Teens in Space, but not in Kids on Brooms or Kids on Bikes. Items work differently as well. The latter two games allow players to choose pretty much anything to put in their inventory at random, while the former requires more specificity and provides stats for many items.

If it wasn’t clear by how much I’ve talked about these aspects, the system is highly focused on characters. Each book starts with some brief worldbuilding activities if the group wants to work on those things together, but that can also be ignored in favor of allowing the GM to put things together. Questions to answer about character relationships take more precedence.

Combat also isn’t really a thing. Some brief rules exist for contested rolls to take over narrative control, but the game is best designed for brief spats or singular attacks than any kind of drawn-out fighting.

Personally, characters are my favorite part of RPGs. In traditional media, we typically see one main character’s interactions with a world and their story. Collaborative storytelling creates an entire cast of complex characters with fully realized backstories and arcs. The fact that this system leans into that aspect is really cool.

“Crunchier” RPGs tend to have to solidify player mechanics so much that it can feel hard to create a unique character. Even my beloved PbtA games halfway create a character for the player. Kids on Bikes as a system allows complete freedom in character creation without losing integrity of rules structure.

The Books

Each book runs around a manageable 100 pages, give or take, some of which is aimed at people entirely new to role-playing games.

Surprisingly few pages are designated for the GM’s eyes only; this may be explained by the fact that all the Kids on Bikes games are meant to be highly collaborative, with players adding to the world and story as prompted by the GM.

Tables of suggested character tropes, strengths, flaws and the rest are included as appendixes. Beyond the art featured throughout the books, this is my favorite part: minimal page flipping was involved when I introduced this game to my table.

Each book had some individual strengths and weaknesses which are worth touching on.

Kids on Bikes

I don’t want to say too much about the original book since I have yet to play with it, but I can say this: the setting suggestions included in the deluxe edition are fantastic. Some took inspiration from media like Fargo, Stand By Me or Twin Peaks, but the first one I plan to run is all about a group of dads who all live on the same cul-de-sac and love to barbeque in their free time solving a mystery.

The really fascinating aspect of this game is that there will always be one character who is controlled by the group. The “Powered Character” is like the E.T. or Eleven of the group, with abilities beyond natural strengths.

Teens in Space

While (sadly) my least favorite of the systems, Teens in Space still has some cool stuff. This is the only book to introduce different species in an official way and all of them are incredibly creative. Not to say a player couldn’t invent their own, but who wouldn’t want to be a brain slug possessing another race, a giant insectoid or a person made of clouds or plants.

The suggested tropes are also pretty great, as is the fact that any game is going to be the most rag-tag and random group of characters you’ll ever see. That’s what RPGs are all about.

However, my problem is that such a combat-light rules system just doesn’t sit right for the sci-fi stories I prefer. In other settings where fights are non-deadly and are usually more quick plot advancement than displays of awesome weapons and spaceships, low combat is entirely fine.

Everything changes when it’s like, I have an irritable brain slug in my head, a gun in my hand and my spaceship can turn invisible. What does the GM even do with me at that point?

Kids on Brooms

I’ll end my review on a high note because I love this version! Young adult fantasy magic often feels entirely different than typical RPGs, which often take after video games, and this system handles unique magic better.

There is quite a bit of content in this book having to do with player safety and inclusivity (both always important) with some obvious nods to a particular author associated with the “magical school” genre. While the specific discussion may have been overwrought, this is a great way to reclaim this kind of story, making it your own.

The system’s cooperative world building shines here. Working together to make a neat magic school and then getting to face everything from bullies to mean teachers to actual monsters is super fun.

Wands and brooms have fun mechanical benefits and going to class can boost your abilities over time. Characters can be underclassmen, upperclassmen or faculty, providing different experience levels and strengths. Your magical strengths reflect your character strengths, but magic has the potential to do anything.

This setting plays on all the strengths of this system with a touch of whimsy which is totally worth checking out if you need to choose just one to try.