Daniel Mersey is a very prolific writer of independent historical games, with a reputation for approachability and an obvious fondness for the Arthurian period. He also happens to be one of my favorite wargame designers.

Into the Merseyverse is my look at this collection of games – what they cover, how their mechanics are, etc. While not quite an exhaustive look, it covers everything that’s reasonably easy to obtain – ranging from trivially so, to “This took a little bit of digging.” It’s a two-parter, because there are a lot of games to cover, and they are presented in no particular order.

Nouns Rampant

First up is what I have somewhat flippantly referred to as “Nouns Rampant”, a series of books published by Osprey that cover an absolutely massive swathe of history, ranging from the Dark Ages (Lion Rampant) to the various colonial wars of the late 19th century (The Men Who Would Be Kings), along with offerings for fantasy (Dragon Rampant) and science fiction (Xenos Rampant). The second edition of Lion Rampant won an Origins Award in 2023.

These games all share a familiar mechanical core that means you can hop between them freely and have a level of casual approachability best described by Lenoon’s encapsulation of Lion Rampant: “Hey man, let’s get a bit pissed and do medieval stuff.” Despite their relatively straightforward mechanics, there’s a good degree of depth and playability to them, and while I play plenty of other games, these are often the ones I reach for when I just want to have a bit of fun.

Shared Mechanics

Activation

The core mechanic to all of these games is in a rolled-activation, push-your-luck system. Push-your-luck based activation is not without controversy it is a decent way to start introducing the notion that your units don’t always do what you want them to. Generally speaking, you decide what you want the unit to do (Move, Shoot, Attack, etc.) and they have a target number you need to roll over on 2d6. Units are more likely to do things they “want” to do, which is also sometimes used to represent slightly different mechanics – for example, Archers in Lion Rampant are more likely to shoot than Crossbowmen, which represents that sometimes the Crossbowmen are busy reloading their weapons.

One nice thing about this mechanic is that it the games to represent the professionalization of armies over time. For example, in Lion Rampant, Elite Cavalry (basically knights), have a move value of 7+, but an attack value of 5+. So while they’re quite happy to charge, they’re much less likely to move without charging, and thus terrible at doing useful things like escorting other units. And importantly, when they fail, your turn is over and it passes to your opponent, so if you really need those Knights to do something they consider beneath them, it might just stall your whole army.

The next game up the line time wise, The Pikeman’s Lament (my personal favorite), sees slightly more professional armies, with Gallopers, the heaviest cavalry unit, gamely willing to both move or charge on a 5+. But if they have second thoughts about the idea (like these poor fellows below who are absolutely going to die), again, your turn is done.

Rebels and Patriots, which covers the various colonial wars in North America up to the Civil War, starts to play with the formula a bit – units now have a Discipline stat that modifies the roll to activate – by default, the roll is 6+ for all actions, but it can degrade as the unit takes losses, etc. And importantly, if your unit doesn’t activate, that unit is stalled, and then you move onto the next.

The Men Who Would Be Kings takes this a step further, as we are now dealing with truly professional armies. Each unit has a leader, who determines how well they’ll activate (sergeants now being important) with more professionalized armies being likely to have more reliable units. Additionally, each unit has a type of action that they don’t have to roll for, and it’s different for each type of unit. We’ll get to this later.

The exception to this “Command and Control Gets Easier Over Time” trend is Xenos Rampant, which uses the core “Activate until you fail” mechanic, but you do get the free single type of activation.

Dice, Targets and Stamina

One of the mechanics that makes these games approachable is figuring out how combat works. Full strength units roll 12 dice, half-strength or disordered units roll 6 (Xenos Rampant uses 10 and 5). You have a target number – that number or over scores a hit. You then compare the number of hits versus your target’s stamina. Each time the number of hits equals the target’s stamina, a model dies, and the remainder are wasted. For example, 4 hits against a target of Stamina 3 will kill one model, while 4 hits against a target of Stamina 2 will kill two.

Owing to the asymmetry of the units involved, The Men Who Would Be Kings bases the number of dice used on the size of the unit itself.

Leaders

In most of the games we’ve discussed, there are also leaders – either singular battlefield leaders, or squad sergeants (for The Men Who Would Be Kings). These leaders tend to just be a model in a unit, and not combat monsters on their own, though they boost morale and make activations easier for units around them. And, if you’re unlucky, they can take a stray bullet, sword stroke, pike, etc. and die – with somewhere between “bad” and “catastrophic” morale consequences. The games set in earlier periods also let your leader challenge an enemy leader to, effectively, a dice off, with the loser being taken out of action. It’s a good way to force that “somewhere between bad and catastrophic” morale test – and if your enemy refuses they have to take that test anyway – but there’s usually pretty even odds its your leader who will come out the loser. It’s a risky gambit, but late turn if you’re behind by a bit but your enemy has taken some casualties (and thus their morale will be worse?), potentially a worthwhile one.

What I Like About Each

We already have reviews for Lion Rampant and Xenos Rampant, so instead, let’s just do a lightning round of the highlights. Again, we’ll go in roughly period order:

Lion Rampant

With a second edition of Lion Rampant being hard cover and with a lot more layout freedom than the “blue books”, this game has by far the most polish. There’s a decent, if somewhat bare bones, campaign system that’s also fairly approachable, and the ability to customize your commander by paying points for traits lets you get exactly the vibe you want.

It’s both a solid game on its own for a really broad span of history (I’ve embarked on a 100 Years War-esque project for it), and a good source to borrow from for the other games.

The Pikeman’s Lament

It’s about the Thirty Years War. The random nature of your commander can make for some extremely endearing and memorable characters – one of mine, for example, has an old wound, and so can be taken out of action slightly easier. We’ve got a full review of Pikeman’s Lament here.

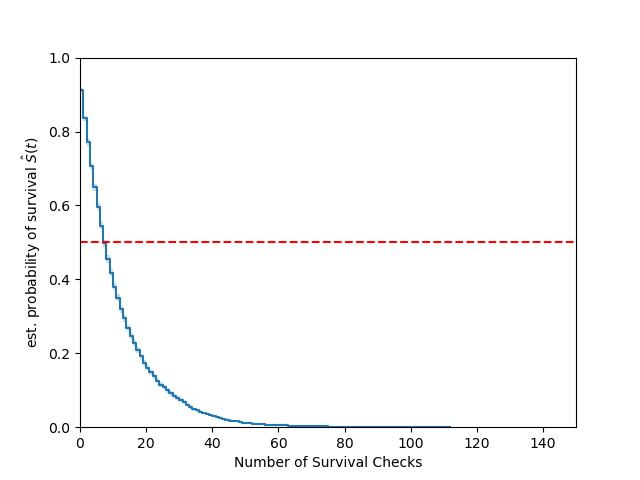

Combine that with a very simple campaign system where you gain experience over time and can, eventually, be promoted to Colonel and thus out of the scope of the game, made for a remarkably nerve-wracking experience as I got close to it. For “fun” I ran the numbers of how many “But did he die?” rolls the average character survives after being taken out of action.

It’s eight.

I took way more than eight.

Rebels and Patriots

I like that it keeps the charming little character campaign progression system from The Pikeman’s Lament, and how well it captures the diversity of potential units that will arise in the period it covers, with suggestions like Union Cavalry during the American Civil War being Mounted Skirmishers, while Confederate Cavalry might be represented by Shock Cavalry.

The Men Who Would Be Kings

The free activation is a really neat addition. It can result in things like your standard British infantry squad being really rather dangerous, as they don’t have to test to shoot, but it also means they’re liable to stall out, relying on trying to kill their enemy, while struggling to get to an objective. I’ve won two games playing the Zulus where my opponent gave me a pretty bad mauling, but got held at the edge of the board due to pressure.

Dragon Rampant

A really flexible fantasy system that I think is a good “gateway” between historicals and fantasy wargaming – the rules crosswalk between it and Lion Rampant is pretty trivial, and the two can definitely steal from each other.

You can have Knights fight Dragons. That’s just neat.

Xenos Rampant

Another good “Hey, if you liked this…” type of game for onboarding people into historical games, getting people going with smaller collections than what it takes to play 40K these days, etc. We really enjoyed it on release, and it’s another really flexible system, that can handle everything from Pulp 1920’s Adventure to modern conflicts to modern conflicts but with aliens to people running around in powered armor.

What I Like About Them All

They’re a really easy way to get started. Starter sets for bigger games are often workable full armies for Noun Rampant games. For example, the Perry Miniatures “English Army 1415-1429” box is a workable Lion Rampant army, while Warlord’s “Pike & Shotte Battalia Starter Army” is a The Pikeman’s Lament army plus some spares and options.

That means they’re also good starting points for larger projects – if you’re planning something for a bigger scale game, getting to something Lion Rampant scale can get you that dopamine hit of actually putting your models on the table well before you’re done with the larger scale force.

The scenarios in many of the books are also charming, and often have a nice, asymmetrical feeling to them that can help get players used to the notion that historical fights aren’t always necessarily “fair”. You can ambush your opponent in their bed, cause a cattle stampede, or raid a town and do your level best to never actually get in combat with each other. They’re also general enough that they can definitely be transported both between games in the series, and probably outside it.

Dux Bellorum

What Is It?

Dux Bellorum is the other Osprey blue book game, this time covering Arthurian-era wargaming in the vicinity of AD367-793. The game itself is again on the smaller side, but is more definitively a “rank and flank” style game, with individual models being grouped onto unit bases. In an attempt to be miniatures-and-scale agnostic (probably wise for an indie game), it saddles itself with the somewhat cumbersome “Base Width” concept that more recently appears in Midgard.

If the theme of the previous games was the gradual professionalization of your soldiers, Dux Bellorum is here to remind you that absolutely no one in this period could field a fully professional army. Units are divided up into Ordinary, Noble and Companions (i.e. your household guard, etc.), with increasing quality. They are similarly divided into Warriors (good at hitting things), Shieldwall (being good at taking hits) and Riders (worse than both of those at their chosen thing, but quite fast).

The core mechanic though is leadership points – those you distribute around your army to represent your commander’s control over their troops, and they can be redeemed for any number of things – temporarily boosting how good a unit is, ignoring hits, interrupting the movement sequence to prevent the escape of a unit, etc.

The rest is relatively simple – you roll dice against a target number, units lose coherence as they take losses (though they do not degrade) and once they hit zero, they’re gone. At 50% losses your units start to waver, and at 75% they break.

What I Like About Dux

I often appreciate wargames that are clearly trying to play around with a concept. It’s often a way to get at representing an aspect of warfare without going completely overboard with the rules. In this case, it’s about a time of legendary warlords. Even in Lion Rampant, your leader isn’t likely to turn the tide themselves.

In Dux, it’s entirely about that.

This is a game about your leader, who is very likely to end up in an epic poem about a cattle raid. But it’s less about them as a warrior themselves, and more about how they wield their army. It feels like a Bernard Cornwell book to me – yes, your hero is dangerous in their own right (them and their Companions are your best unit), but there’s also that aspect of them always being in the right place, at a pivotal moment, calling orders that will turn the tide. It’s a cool concept, can result in some cagey and interesting gameplay, and is an excuse to go ham on your warlord’s base.

There’s also a neat mechanism in the army selection process, where some armies have a boost to their “Aggressor Rating” – for example, the Late Romans are 0, while the Irish are +3 and Raiders from both Land and Sea are +5. This means they’re likely to be the attackers, but it’s not promised. It’s a nice sort of mechanism to build an army around, with just enough variability that your buddy’s Irish can’t be built on the assumption that they’re always the logical attacker.

+STRONGSWORD+

This game, which I’m just going to call “Strongsword” from now on, was published by Westfalia Games in 2017, and took some finding to get ahold of, which is a pity, because it’s adorable.

What Is It?

In short, it’s a game about mobs of weird little guys. Or ladies. Or nonbinaries. But definitely little weirdos. Again, we have some playing with mechanics here – because you’re playing an unruly mob with no unit cohesion, tactical nuance and the like are out the window. Instead, you secretly select one of six stances, ranging from a very defensive one that lets all of your units move away and some of them try to rally, to a very aggressive one where everyone charges – even the archers.

You can’t pick the same one twice, and the obvious dynamic is trying to anticipate both what your mob needs, and what your opponent is likely to do. This seems both fun and very easy to explain to someone just making the leap from RPGs or with no wargaming experience at all.

A fairly simple d10 based combat resolution mechanic (love a d10) is included, and hijinks ensue.

The whole thing is written very tongue-in-cheek, with the traditional “Rule 0” type rule being named “Rule 74.10, Clause 18” as a quick example.

How big of a mob are we talking? Following their mob creation rules very roughly, my Sisters of Sigmar Mordheim warband is pretty close to appropriately sized. A force of Kobolds will be…more. About three times more.

What I Like About Strongsword

As someone who runs at least one event a year introducing people to wargaming, “Easy, Fun, Tongue-in-Cheek Antics” has an obvious appeal, and part of me is already planning next years “Hobbits vs. Kobolds” feud game.

If Louise Sugden saying “Weird Little Guy” is something that triggers an auditory memory, or if you backed Half Tilt and want more of that, or generally in a world currently enamored with Trench Crusade if you just want something bright and whimsical…I’m sorry this game will be hard to find, but it will definitely be worth it.

That rounds us out for this part of our deep dive into the collected works of Daniel Mersey. What’s up next is another series of games, the “You Command” series, alongside some of his older works.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.