It’s easy to think of 1989 as belonging to a different age: The fall of the Berlin Wall and Tiananmen Square. The first Batman movie. The birth of the world wide web and the first commercial internet service providers.

It was also the first year for Warhammer fiction, starting with Fantasy and branching into 40K the following year. It would be easy to look upon those founding works as relics of a different age themselves- and in many ways they are- but while many of the authors and works may be unfamiliar to the modern audience their legacies are very much relevant. As we’ll see, without one of our founding authors- who wrote but a single short story for the Black Library1 – Baldur’s Gate 3 might look very different indeed.

Just ask Lae’zel. Nicely.

But for now, back to 1989. To really set the scene for Games Workshop’s foray into fiction, it’s important to note that the practice of established gaming properties incorporating novels into their intellectual property (IP) repertoire was well-established following the success of the Dragonlance saga.

Launched in 1984 with Dragons of Autumn Twilight, TSR quickly found that novels were a great way to broaden the reach of their products even to non-gamers as novels did not require any working knowledge of role-playing to enjoy. They’d already leaned into the publishing space with the Endless Quest series of choose-your-own-adventure-styled books, which by the time Dragons released was already sixteen books deep.

TSR would continue to set the tone with novel releases for its existing adventure settings, releasing novels for Greyhawk in 1985, the Forgotten Realms in 1987, and- in 1990 (when our 40K tale begins)- Spelljammer. Plenty more were to follow.

Other book and gaming companies weren’t standing still. FASA introduced novels for Battletech with 1986’s Decision at Thunder Rift. Puffin Books, meanwhile, had been releasing the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks since 1982 and unveiled its own first novel in 1989 with The Trolltooth Wars.

In short, when Games Workshop decided to begin producing Warhammer fiction, it was already well-established practice. An additional potential revenue stream for already-developed intellectual properties.

1989 was the kickoff year for GW, and they opened with two novels (Drachenfels and Zaragoz) and two anthologies of short stories (Ignorant Armies and Wolf Riders) for Warhammer Fantasy. Those wanting tales set in the grim darkness of the far future, however, wouldn’t have long to wait. But who to tap to give voice to the nascent Warhammer 40,000 universe, which had just come into being in the Autumn of 1987?

Enter Ian Watson.

“British SF in the 1970s belonged to Ian Watson,” says David Pingle of Foundation.

“Watson may not be the best writer in British science fiction, but he is probably the best thinker,” enthuses Peter Nicholls of Encyclopaedia of SF fame.

“There is no other writer in the field who provides such a bold challenge to the imagination,” insists Brian Stableford.2

Watson was no aspiring writer finding his big break in genre fiction for a fledgling property. Rather, by the time he was tapped for Warhammer he had already won the Prix Apollo in 1975 and British Science Fiction Association’s Best Novel Award two years later.

For those whose sense of time might require a more modern reference, don’t worry; Wikipedia has got you covered3:

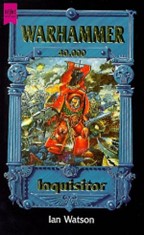

All this is to say that Ian Watson was a name, a get, someone with some heft in the genre when he sat down in front of the typewriter and began to compose the story of Inquisitor Jaq Draco. What he came up with is a pretty wild ride, one that ultimately while not outright disclaimed, had to be contextualized by Games Workshop and compelled the release of a revised version (renamed Draco) twelve years later.

“It’s a glimpse at a not yet fully formed version of Warhammer 40,000, in which squats still exist, and other weirdness abounds. It’s fascinating and a mind-bending tale by a renowned SF author – just remember that it’s not Warhammer 40,000 as you know it!4”

In Inquisitor, Draco uncovers a psychic plot to enslave humanity involving the machinations of a secret society within a secret society within a secret society (not a typo) that takes Draco and his retinue from a Genestealer-infested world to a chase through the Warp, to a Chaos-world in the Eye of Terror, and finally to Terra and a chat with the Emperor.

‘NOTHING THAT SAFEGUARDS HUMANITY CAN BE EVIL, NOT EVEN THE MOST STRENUOUS INHUMANITY. IF THE HUMAN RACE FAILS, IT HAS FAILED FOREVER.’ -The Emperor of Mankind5

If that all sounds a bit like Warhammer-cum–The Illuminatus! Trilogy6, have some sympathy for Watson who was essentially being asked to build a building without a blueprint. Today’s new Black Library authors are given some basic resources and work closely with their editor to ensure canon fidelity7, as well as a huge volume of pre-existing works and lore to guide them.

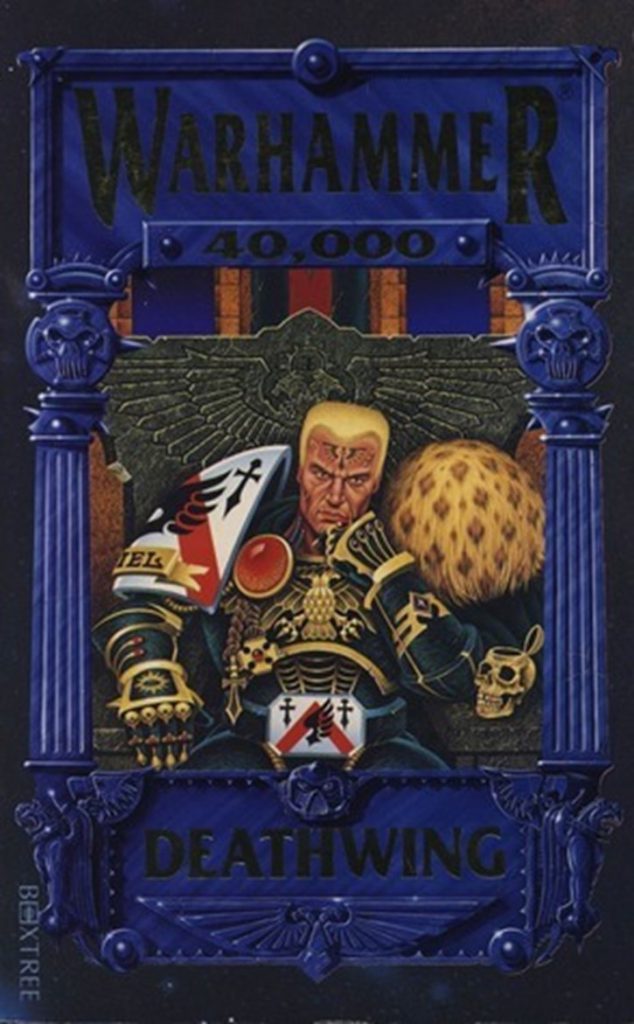

Watson’s madcap romp through the stars may have been 40K’s first published novel, but it wasn’t the only book released in 1990. Deathwing was a short story anthology with a fascinating roster of writers, most of whom never wrote for the property again.

Bryan Ansell & William King, Deathwing

Fitting that we’d start with Bryan Ansell, a towering figure in Warhammer history whose one dip into Warhammer fiction was co-authored with stalwart William King. In addition to being the founder of Citadel Miniatures in 1979 and subsequently Managing Director of Games Workshop, Ansell was no stranger to writing. He penned the very first edition of the game in 1987 (Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader) as well as a number of subsequent publications.

Deathwing tells the story of a Dark Angels Captain, Ezekiel (also known as “Cloud Runner,” as the story’s setting draws heavily from a Native American influence). He returns to his birth world to recruit more warriors- only to find a Genestealer menace awaiting him.

William King, Devil’s Marauders

William King, meanwhile, had only joined Games Workshop in 1989 but would be a prolific author for years to come. He’d already had three short stories published for Warhammer Fantasy by the time Deathwing saw print, and his characters Gotrek and Felix would be some of Fantasy’s most beloved creations.

Devil’s Marauders is the story of the survivors of an Imperial Guard regiment racing to cross a Xenos- and heretic-infested jungle to get to safety before a pending Exterminatus order is carried out.

Ian Watson, Warped Stars

There was an explicit sexual element to Watson’s work that was more characteristic of him as a writer rather than the eventual tone of what would become the Black Library, and Warped Stars is a fine example. Here a young psyker develops contact with an “imaginary friend,” one which happens to be a daemonic entity hell-bent on persuading his new “friend” to open up a Warp portal.

Storm Constantine, Lacrymata

Constantine’s career saw her write a lot of genre fiction, so her one involvement with Games Workshop is perfectly on-brand. She worked at the local library, was deeply involved in the Goth scene in Birmingham (even serving as manager to a few of the bands), and gave outlet to her lifelong passion for storytelling through writing.

In 1990 she was on the ascent, with the third of the acclaimed Wraeththu Chronicles trilogy coming out just the year before. The series involved an alternative reality where humans transformed into psychic hermaphroditic androgynes looking to rebuild society amongst humanity’s decline. The series’ first book would go on to be a Lambda Literary Award for Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror finalist the following year, in 1991.

Her short story, Lacrymata, similarly deals with the themes of transgressive love, being the story of a romance between a Navigator and Astropath aboard the Imperial trading ship Dea Brava. Far from a fossil, the story is often referenced even now both for its depiction of navigation as well as its central romance element.

Charles Stross, Monastery of Death

Okay, this one’s wild. You might not have heard of Charles Stross, but there’s a good chance you’re at least familiar with Baldur’s Gate 3.

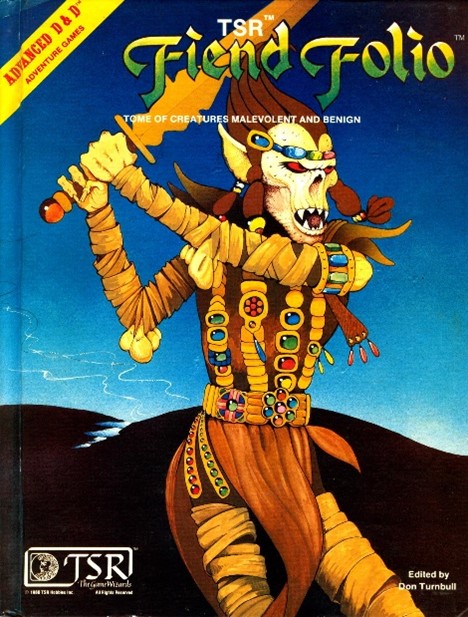

In 1981 TSR released a compendium of monsters called the Fiend Folio. Unlike the earlier Monster Manual, the Fiend Folio took much of its content from creatures created in the pages of White Dwarf Magazine. One of the contributors was Charles Stross of Leeds, who had submitted the Death Knight, Slaad, Githzerai, and the Githyanki, a race of astral beings immortalized on the Folio’s cover by artist Emmanuel. They’re also the race of one of the main companions in Baldur’s Gate 3, Lae’Zel.

Now if that’s not enough convergence, here’s one more. The name githyanki? Stross had borrowed that from a 1977 novel Dying of the Light– penned by none other than George R.R. Martin. These circles are smaller than we may sometimes think.

While this was his only Warhammer contribution, some of Stross’s other work has been nominated for the Nebula Award, Hugo Award, and Arthur C. Clarke Award.

The story deals with an Imperial delegation coming to integrate a newly-discovered low-tech world, but one that holds an extraordinary secret- an intact Standard Template Construction library hidden within it.

Neil McIntosh, Seed of Doubt

What would this early murderer’s row of incredible talent be without one good mystery? Neil McIntosh appears in 1990 with a short story for Deathwing– and then outside of a story printed in White Dwarf (Black Sail in issue 142, 1991) disappears for a full decade.

Resurfacing in the new millennium, he pens a trio of short stories for Warhammer Fantasy, one each year from 2000-02, as well as some work for Inferno! (a Warhammer literary magazine from Games Workshop). At some point he’s proven his chops to the Black Library editors and a trilogy is greenlit for him to author that launches in ’02 with Star of Erengrad and concludes three years later with Keepers of the Flame. This “Stefan Kumansky Trilogy” is the last we see of McIntosh for Warhammer.

His author bio for the Bill Goodall Literary Agency notes that he moved away from fantasy and science-fiction into the realm of psychological thrillers involving forensic psychoanalysis, and that his 2019 novel Damascus was shortlisted for the Big Issue / Harper Collins crime writing prize.8

Except…I can’t find Damascus anywhere. No copies on Amazon, nothing on eBay. That Big Issue shortlisting definitely happened9, but of the book there’s no sign at all.

Ian Watson, The Alien Beast Within

Having started with Watson, it is perhaps fitting that we end with him as well. In The Alien Beast Within we have a tale of a Callidus Assassin, Meh’Lindi (one of Inquisitor Jaq Draco’s intrepid companions) looking to infiltrate and destroy Genestealer cult.

So… there is 1990, the kickoff year for Warhammer 40,000 in fiction and after these first two books, Inquisitor and Deathwing, things go silent.

They’re silent until 1993, which would ultimately be the longest-ever gap in Warhammer 40K fiction. And then along came Space Marine.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this look at the origins of today’s Black Library. I’m excited to join the Goonhammer team and we’ll continue to look at how the Black Library evolved and grew throughout its long history, year by fascinating year.

Next time, we’ll look at Watson’s eyebrow-raising entry into Astartes lore as well as the completion of the Inquisition War trilogy- all leading up to the seismic year of 1997!

Footnotes

1. Technically, the term “Black Library” doesn’t come into usage until 1997 when it was launched as a publishing company to produce Inferno! Magazine

2. Taken from Ian Watson Interview (1981)

3. From A.I. Artificial Intelligence – Wikipedia

4. From Black Library – Draco (eBook)

5. From the conversation between Draco and the Emperor in Inquisitor. The Emperor did, indeed, speak in all caps. As one does.

6. fnord

7. From a Reddit AMA: Ask Me Anything – Steven B. Fischer : r/40kLore

8. The only trace of the elusive Neil McIntosh I can find, and it’s here: Neil McIntosh – Bill Goodall Literary Agency

9. The suspense is over: Big Issue crime-writing winner announced

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.