This article will contain spoilers, general and specific, for Immortality. There will be another spoiler warning when specific story discussion begins.

Immortality is pretty close to being my game of the year. And I was pretty sure that selection was locked in at Elden Ring somewhere around early April.

Generally speaking, people aren’t stupid. They’re actually incredibly smart in very specific, localized circumstances. What people aren’t very good at is abstraction, and the ability to exert empathy via abstraction — not that they have a lot of great outlets to do it over in the modern world (social media certainly isn’t one). There are a lot of consequences of our general inability to abstract now that we’re all connected such as we are, everywhere, all the time, and one of the more minor ones — but one of the most relevant to this review – has to do with media literacy.

Abstractly, it’s really difficult to consider or care about a single thing that actually goes into making the discrete nuclearized product called “a movie.” You have no feeling for or familiarity with what’s going on behind the viewpoint of the camera. In the past this led to auteur director and actor worship (think about how many guaranteed mega draw directors and actors there were even in the 90s, and now it’s like five guys and Tom Cruise) and mechanical fetishism — love for the fact of the film itself, and changing it, and the shutters, and so on and so forth. Now, Disney openly states their business model is to film everything in a shoddy, hideous greenscreen version of the holodeck from Star Trek. They even have a dystopian, ominous name for this (“the Volume”). The idea is that everything can be done by outsourced, overseas, underpaid and overworked VFX artists, and craft in the real world is simply obsolete (especially if it involves unionized labor).

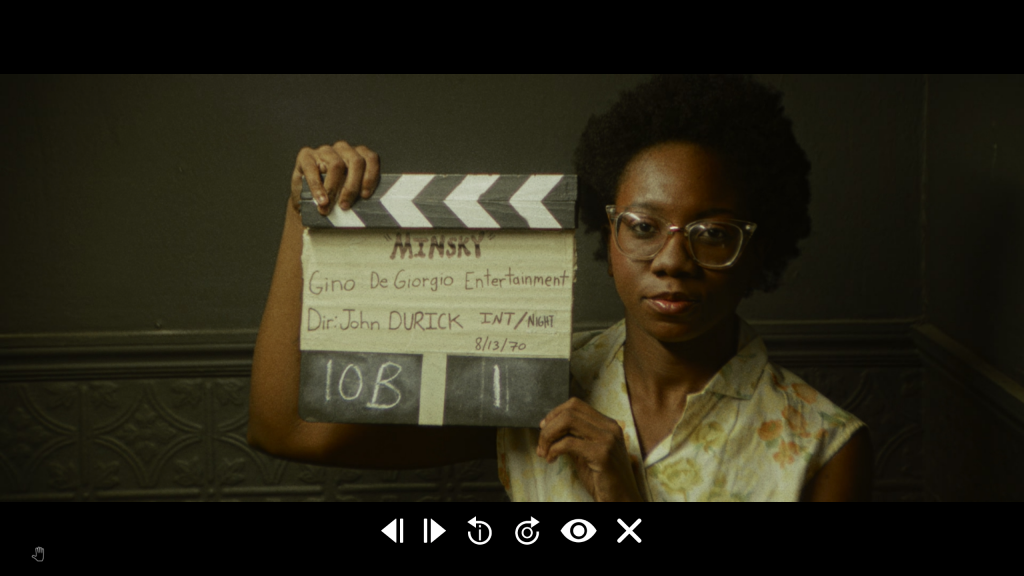

So what does Immortality do? Well, the basic form of gameplay is that to start with, you’re handed a 15 second to three minute long clip of raw footage — pre-assembly cut, pre-cutting room footage. Basically this means you see everyone from the crew in the shot before “Action” and after “Cut,” and are clued in on all the actor reactions and offscreen hollering from when the camera starts rolling to when it stops. And it’s not just footage from shooting, either — rehearsal, media interview, and crew party footage clips show up as well. They’re presented the exact same way as the raw film clips, intentionally blending and blurring the line between film and content.

When you’re presented with one of these clips, you’re permitted to move backwards and forwards across it, and then pause at any time to enter “Image Mode.” This allows you to take the cursor, find some interesting image in the particular paused shot of the clip you’re in, and activate it, assuming the empty circle of the cursor fills with an eye marking. Activating that eye jumps you to another clip in the game’s film library, associated and linked by the visual image you clicked in some way. In the most basic sense, this means highlighting an actor’s face and jumping to a clip with the same actor in a different context. In the more complex senses, it means focusing on a brief glimpse of a theme and following it through multiple clips you’ve already explored to find a brand new one — or locating a cast member who persists briefly across multiple clips, never the focus but always present.

That’s the basic gameplay loop — but along with it comes an extremely well-produced and well-calibrated audio library and a fantastic use of controller rumble, if you’re playing it with a controller (I would actually advise that, given both the presence of rumble and how much better using two sticks to isolate portions of a film clip is than mouse and keyboard). Once you reach the second level of what the game’s presenting, you’re going to need that guidance. Because it’s about to get weird.

After this point in the review there will be specific story spoilers for Immortality.

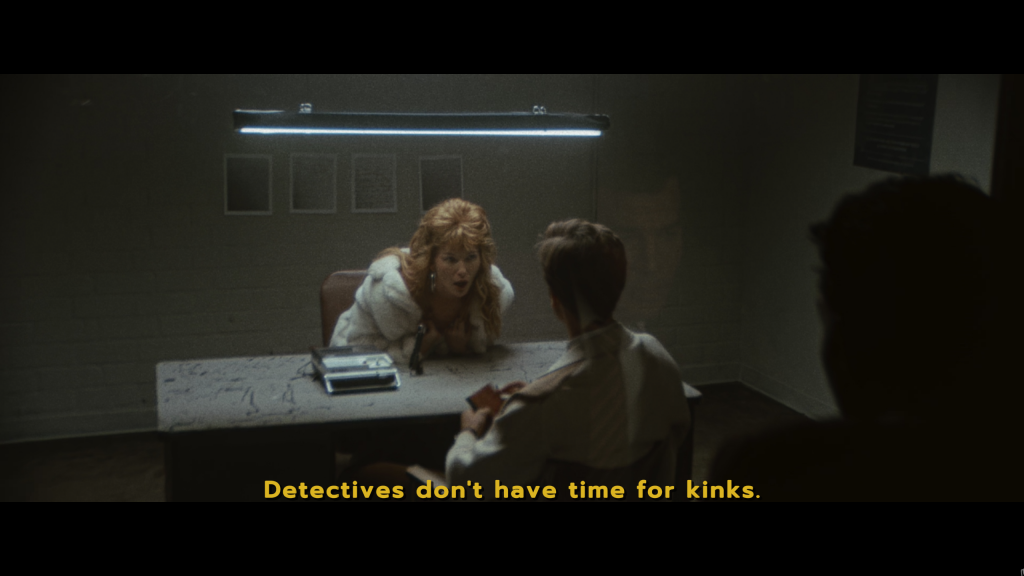

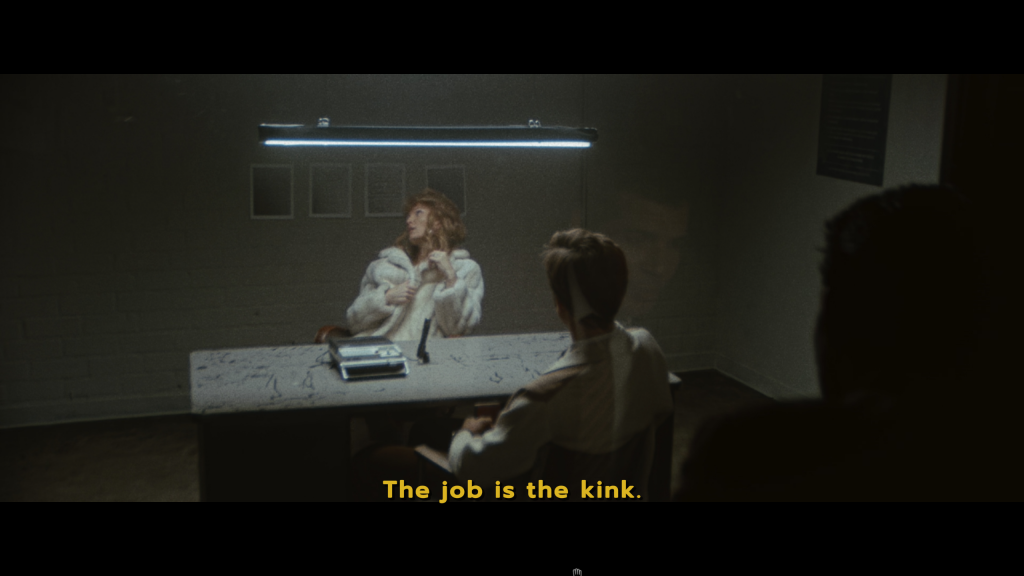

The films in Immortality — there are nominally three of them, made in 1968-9, 1970-1, and 1999, all starring the same actress, who has vanished from the face of the earth with none of these three films, her only work, published or released — are lovingly rendered for their eras. This means an Italian softcore horror aesthetic for “Ambrosio,” the heaving-bossom sexploitation film about nuns and inquisitors fucking each other; it means a grainy American seventies aesthetic for “Minsky,” the grungy crime not-quite-De Palma-classic that concerns a serial killer who has killed a lesser self-styled Warhol artist-cum-sex criminal and is now working their way through the women he abused; and it means a flat, antiseptic, television movie rendering for “Two of Everything,” a rote Lifetime-style ‘thriller’ about a pop star who is murdered while the body double is impersonating her in public, forcing the body double to assume her identity.

One of the best things about Immortality apart from the gameplay or the story of the actual game beyond is how well these three films communicate their vibes on set — “Ambrosio” is a bunch of young Americans on an awkward near-study abroad experience to Italy, where a bunch of old Italian men leer at the women and everyone under thirty fucks in the bushes; “Minsky” is an attempt at High Art that sees our heroine and star actress throughout these three films, Marissa, make a genuine connection with the young lead actor through the rehearsals and the parties and the actual scenes, while still lingering on the director, who was involved in “Ambrosio” as well; and “Two of Everything,” made many, many years later after the fallout from “Minsky” — and with the same director/DP, John Durick — is a rote cash-in where almost everyone is embarrassed to be there and extreme backstage politics make themselves violently felt.

The alleged main character of this game is Marissa Marcel, played incredibly by Manon Gage, and the alleged story is that she made three movies — two between 68 and 71, and one in 99 — and then vanished without a trace, with none of the films being released. A somewhat more honest description of what’s actually going on here is that two cenobites — as in the beings addicted to and never satisfied by pleasure from the Hellraiser series — have found themselves in a slice-of-life narrative, and are deeply tormented by it. The One, played perhaps even more memorably by Charlotta Mohlin, tries to regain true pleasure and meaning through film narrative, seeking always the Artist, played by Justin Sorvillo, whose motives range from hedonistic to churlish to childishly oppositional. The One is, over time and across films, less concerned with the Artist than she is with you, the actual protagonist of the game (rather than its main character), the viewer and the consumer of film. The consumer of Content. And then, at the end of everything, the One makes the final leap.

This incredibly and successfully audacious overplot isn’t to take away from all the underlying stuff — Mohlin is amazing, but Gage and her co-stars are fantastic, and Gage in particular should be a star off of this given how much work she puts into the product (it helps that to really sell the game, they paid to have Ambrosio, Minsky, and Two of Everything entered into IMDB with the full casts as if they were full, real films). Everything builds, clip upon clip, into a raging climax that literally overwhelms your senses and consumes the UI — but the underlying story is fantastic, full of great character work that has almost nothing (almost) to do with the immortal tormented creatures dancing through the editing room. There is perhaps in my generation — I’m somewhat newly 36 — a stigma against games that use real actors. FMV games. None of that should apply here. Everyone involved with this game came to work and acquitted themselves fantastically, even including the actors in Two of Everything, which is kind of underwhelming except for the scene when someone lights a mannequin representing Marissa on fire and if you pay close attention, every now and then, the mannequin is blinking.

Final Verdict

It’s on Game Pass now, and has an MSRP of $20. I’d buy it at $40. It’s still probably 5-8 hours of content if you’re going through it at high clip, but if you just want to flesh out the underlying movies, there’s probably about 20 hours of footage seeking in there. Might be a true ending that I didn’t get in my rush to turn this review around, too.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.