A Japanese Type 93 torpedo – known generally as the “Long Lance” even if the original owner/operator never called it that – is 20 feet long and weighs as much as a car. It’s a cylinder two feet across, full of compressed oxygen and explosives. If you mess up handling it, or sometimes even if you don’t, it will absolutely blow up and kill you. Reloading a tube in combat must have left like rearranging furniture in a rainstorm, during an earthquake, while being shot at. There are tools aboard – cranes and pulleys – but imagine 15 teenage parking lot valets in a hurricane being given an electric winch and a pallet jack, and told to re-park all the cars in a crowded lot without turning any them on, and if they ding or scratch a single one they’ll all be murdered. I never quite realized how bonkers a practice carrying, firing, and reloading torpedoes was, until I was idly twirling the launchers around on their little mountings on Tamiya’s 1/350 Yukikaze.

I could, in theory, have had these thoughts without a model ship to prompt them, but I didn’t, and there’s a real question as to whether it’s good that I did have them. Model boats, then: a learning toy.

I’m not sure why I find the Imperial Japanese Navy as fascinating as I do. Ultimately, it probably has to stem from my father, who was in the United States Navy for the first 17 years of my life, but the proximate cause is more nebulous. I do like big boats, but why I attached to this one specifically is unclear. Best I can figure is that the Japanese Navy simply does not exist anymore, so it has the allure of the unknown.

When I say it doesn’t exist, I mean both as an institution (the modern Maritime Self-Defense Force doesn’t officially descend from, or share anything but some ship names with, the IJN) and in terms of historical artifacts. It’s easy to forget, living in America where we have half a dozen battleships, multiple aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and even sailing ships, that preserved warships are actually exceedingly rare. Just here in Baltimore, we have a World War 2 submarine (which rules, definitely check that out if you’re in town), the sailing ship Constellation, and a Coast Guard cutter that is the last surviving veteran of the attack on Pearl Harbor (a less-cool fact about this one is that they had to rename it recently, because it was originally named after a dude who was insanely racist). The battleship New Jersey is two hours away, and her sister Wisconsin is three hours in the other direction.

In comparison, the Royal Navy, the inventors of the modern dreadnought battleship and the ones who produced more of them than anyone else, has nothing beyond a few destroyers. The only existing British-built battleship in the world, oddly, is in Japan: the pre-dreadnought Mikasa, embedded in concrete. The Italian Navy? Gone. The German navy, in both Kaiserliche Marine and Kriegsmarine forms? I think they have one submarine from each war, the rest are littering the floor of the north Atlantic. In the early 1900s there was an entire naval arms race across most of South America, but not a single one of those ships have survived, from any country. The Japanese Navy is a somewhat different beast. It disappeared early, most of it ceasing to exist from 1942-1945. There was never a chance to preserve any of it.

I actually ran the numbers on that one, and the number of ships that survived 44-odd months of combat against the US Pacific Fleet are so slim that you can learn them by name. Of the Japanese battle line of a dozen modern capital ships, the Americans sank ten, and one (Mutsu) exploded at her moorings, leaving only poor Nagato to be sunk in bomb tests. From 25 aircraft carriers, two survived – the light carrier/training ship Hosho, and the Katsuragi. That’s fewer survivors than were sunk on multiple individual days of the war (four at Midway, and three more at the Philippine Sea – the USN was eating good in those years). Of 18 heavy and 27 light cruisers, by the end of 1945 there were only 2 (Myoko, Takao) and 3 (Kitakami, Kashima, Sakawa), respectively. That is a spectacular reversal of fortune.

But I’m mostly here to talk about destroyers. Between inventory at the start of the war and new construction, I count 192 total. Fully 40 of them survived, but if you (as I like to do) discount the second-line and obsolete Matsu types from those numbers, the number is closer to 8 out of 160. These were mostly handed off to the Nationalist Chinese or Soviet Russian governments as war prizes or, as with Nagato, “expended” to evaluate the effects of atomic bombs.

One of the later destroyer classes, and in many ways the best, was the Kagero. Large, and with an almost perfect balance of guns, torpedoes, speed, and seaworthiness, held back only by the same lackluster 25mm anti-aircraft gun that every Japanese warship suffered from, the Kagero set the standard for what a modern destroyer should look like. Nonetheless, they met the same fate as every other class: completely decimated by American airplanes and submarines. Of the 19 launched, 18 sank. Only Yukikaze made it out, and not for lack of trying. Despite running a hundred convoy escort missions and being an active participant in every battle from the early days in the Solomons through to the Marianas, Philippines, and a suicide run to Okinawa, she never took a single hit from an Allied shell, torpedo, or bomb, just a couple of strafing runs from aircraft machine guns (as an aside, imagine waking up in hell and you’re the one and only guy from your ship’s frankly unbelievable tour of duty that actually got himself murked. Must’ve felt like the world’s biggest chump). It was an unprecedented run of insanely good luck that only ran out in the late 1960s, when her second career in the Taiwanese Navy eventually ended with her being chopped up for parts.

Other than a few scattered artifacts – a gun barrel, a bell, an anchor, often not even that much – you can’t see these ships in a museum anywhere. The technical data are often lost, even, between American fire bombings (for war crime reasons) and Japanese burnings (for security reasons). What was probably the third most powerful navy in the world in 1941, including easily the most dangerous single fleet formation, simply disappeared, under the water or into scrap heaps. In America we have such an abundance of preserved warships that you can leave with parts of them – I own a zinc anode from New Jersey and a piece of original teak decking from North Carolina – but nowhere else can you even visit one, without a submarine. And we all know how that one can play out.

What everyone does have, at least, is plastic model kits, which isn’t the same but does allow you to hold the thing and get a sense of it in three dimensions. I picked up the Yukikaze because I had a rough idea of her story as a “lucky” ship and, honestly, because I’ve been maining Japanese torpedo destroyers in World of Warships for like a year, but it wasn’t until I was building it that I went fully off the deep end. I learned quite a bit from this, my first ship kit and the first non-warhammer model I’d built in years. Mostly about models – this was my first experience with photo-etched parts, and I had to up my tweezer and masking tape game. I didn’t do a great job here. There are some gaps, despite the typically excellent Tamiya parts-fitting. I don’t own an airbrush or any oil washes, and I’m not a great painter. The primer fuzzed and cracked on me, so I had to sand down one entire side of the ship and ruin the detail (sharp-eyed readers may have noticed that all the pictures in this article are of the starboard side, and that’s why). But the project also got me reading and thinking about the actual ship the model is based on, and poor fuckers who had to sail on ships like her. I am now fully boat-pilled and hull-mogging. I have opinions about naval guns. How did this happen to me.

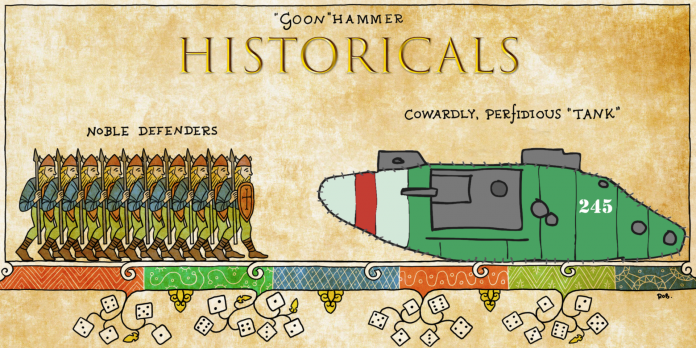

This isn’t a historical wargaming miniature, but I think a lot of the same impulses apply. That is, in addition to a cool thing that decorates my desk, the boat convinced me to learn some Facts. You may wish to do the same. I would encourage that.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.