In Hammer of Math we cover key topics in statistics, probability, and math for tabletop wargames.

Last week we ran an article from Zach Bair called Stop Competing: Embracing Being Good Enough, in which he talked about setting reasonable expectations for yourself and being realistic about what it takes to be a top player and make the top tables – and how to live with yourself if you don’t put in that effort. It’s a great article and we recommend giving it a read.

Now, let’s talk about the other side of that equation. Specifically, what if you aren’t sure you want to give up on your dreams and embrace being good enough? What’s it going to take for you to become one of the game’s top players? Well, let’s talk about expertise.

What it Takes to be an Expert

The common adage, popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in the book Outliers: The Story of Success, is that to become an expert at something, you have to practice it for ten thousand hours. Like most of the things Gladwell wrote, that’s not exactly true, but it’s not a bad place to start. There’s a particularly good video from the YouTube channel Veritasium on this, in which they go into more detail on what it takes to be an expert, and they generalize it to something more like ten thousand attempts, but with some very specific caveats. Specifically, that for you to be able to become an expert at something, you need:

- Repeated Attempts with Feedback. Rather than hours, research suggests that it’s more that you need around ten thousand attempts, and those attempts have to provide feedback. In Warhammer, this is not a problem. At the very least, we have the feedback of winning or losing the game, and often we’ll have more immediate feedback of seeing our overly aggressive move backfire. “Attempts” is a bit more nebulous here, but we’ll come back to it later.

- A Valid Environment. You need an environment where you can actually make valid decisions – you can’t actually become an expert at predicting coin flips, for example. While Warhammer is a dice game, there’s more than enough strategy in the game to make up for that, and give good players a chance to rise to the top.

- Timely Feedback. You need to get feedback pretty quickly to actually learn from your decisions and mistakes. If it takes too long to get feedback, your brain struggles to learn and adjust, making it difficult to improve. The good news again is that Warhammer is great for providing this – at most you’ll have to wait a couple of hours to see how things turn out, and in-game decisions will provide feedback quicker than that as you lose units or points.

- Deliberate Practice. It’s not enough to just play ten thousand games, or to log ten thousand hours – you have to regularly push yourself to practice things you’re bad at and practice at the edge of your ability. If you aren’t constantly testing yourself, you’re not actually going to improve. The easiest way to do this is to play against good opponents – better opponents will challenge you and teach you more, but it can also mean playing against a wider variety of opponents, and going up against armies you haven’t played before.

So let’s talk about what this means for Warhammer.

Ten Thousand Games?

When it comes to Warhammer, we theoretically have a perfectly discrete stand-in for an “attempt” in the form of a single game. And games have plenty of built-in, timely feedback in an environment that’s valid enough for real expertise. And you could certainly play them against tougher and tougher opponents – events already have a built-in mechanism for that, pairing you against players with the same record each round, guaranteeing that as you win more games you’ll play tougher opponents.

But actually playing ten thousand games? Most events will give you three games per day, so if you play in a six-round GT every weekend, that will give you 312 tournament games in a single year, eating up every weekend you’ve got. But you’ve got five more days in the week, right? Well, let’s assume you took out those 312 tournament games, leaving you with 9,688 games left to play. If we assume 2.5 hours per game – the length of most tournament rounds, then it will take you about 24,220 hours to log those ten thousand games. And on that note, I have some bad news for you: There are only 8,760 hours in a year – and you need to sleep for at least a third of them. So to hit this mark you’ll need to play multiple games per day, every day, for four to five years to become an expert at the game.

But that’s not really true, is it? Surely there are already experts at the game, and they haven’t played ten thousand games, right? (spoiler: they haven’t) So let’s go back to that ten thousand hours count – we can justify using that here, as each game is a series of decisions, including deployment, movement, shooting, combat, and scoring over five rounds. Ten thousand hours is still a bit much – four thousand games, so it might make more sense to look at turns – ten thousand turns is roughly two thousand games, and as we’ll see, that might be the ballpark we should be looking at.

Either way, if you want to become a top Warhammer player – or at least an expert at the game – you’ll need to log a lot of games. Let’s find out how many.

Talking to the Experts

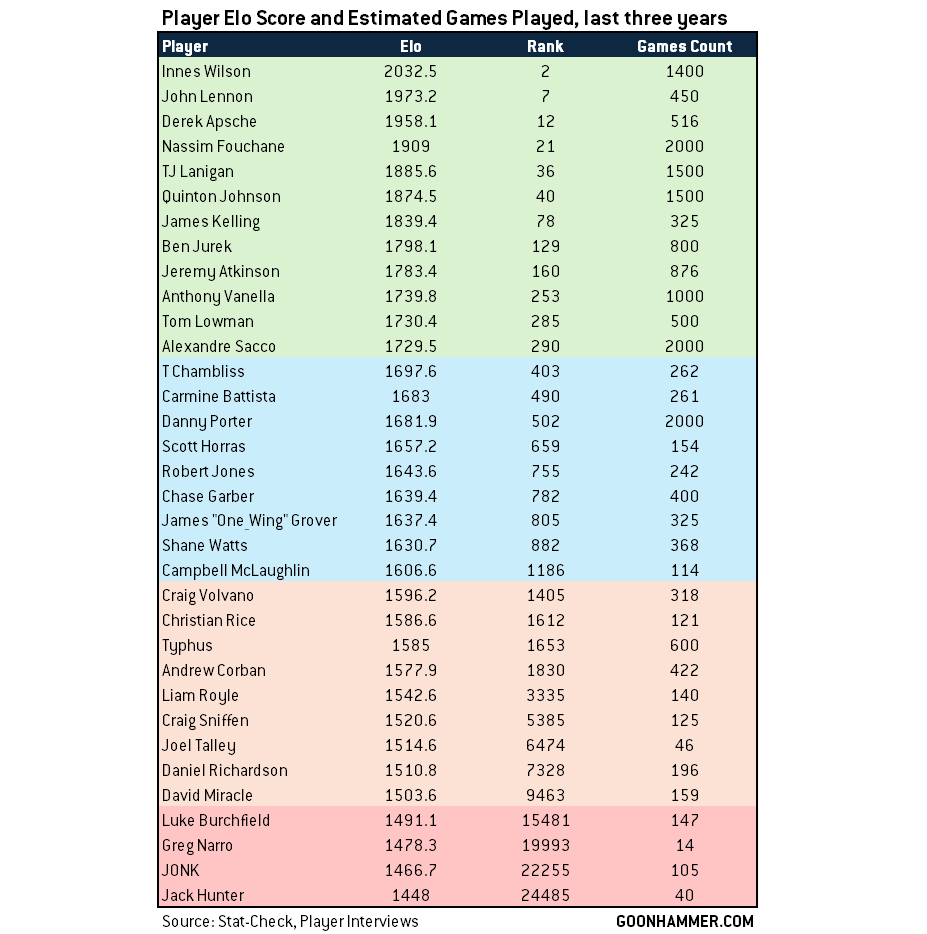

Another way to approach this is to the game’s expert players and ask them how many games they’re logging, and how many they’ve played over the last three years. I can start with my own personal journey in that regard – I’m far from an expert, but in 2021 I started making an effort to improve – not necessarily to hit the top tables, but to get better at the game, to the point where I could write credibly about it for the site. I played 27 games of Warhammer 40k in 2020 and in 2021 I played 85. Then 102 in 2022, 68 last year, and so far I’ve played 72 in 2024. That puts my total over the last three years at 242 games, and since then I’ve won my first RTTs, gone 7-1 at a major, and I’m currently ranked 755th in Stat Check’s Elo with a score of 1643.6.

So how does that compare to the other top competitive players who write for Goonhammer? I asked our comp crew, plus a few other folks on various Discords. The results were very interesting and incredibly telling. Answers among the top players ranged from “over a thousand, easy” to the low 300s. Everyone with an Elo score over 1700 threw out a number over 300, and everyone over 1900 threw out a number over 450. The outliers in these groups were James “Boon” Kelling, who has been dropping his game counts since having a kid, and John Lennon, who said he seldom plays games outside of streams and events now. On the other hand Innes Wilson, Nassim Fouchane, TJ Lanigan, and Quinton Johnson all threw out numbers in excess of 1200 games, and newcomer Derek Apsche threw out 516 as his game count over the last three years. Ben Jurek, Jeremy Atkinson, Anthony Vanella, and Alexandre Sacco also had numbers in excess of 800, and Tom Lowman threw out a number closer to 500.

Just so we’re clear, if we assume 2.5 hours per game, 1200 games comes out to a total of 3,000 hours. And when you take our 8,760 number from above and take out time spent on things like eating, bathing, painting, and other necessary pursuits, that’s basically one entire year of doing nothing but playing games in your spare time. Which is why for pretty much all of these top players the path to the top of the standings was a multi-year undertaking, usually a 2-3 years.

For the 1600 club, game totals tended to be more than 100 games, and this group were a mix of people starting to play more games and increase their reps (Campbell), older players who were decreasing their reps (Chase, Shane), and mid-card players reaching the limits of what you can achieve while being a dad with a full-time job and home life.

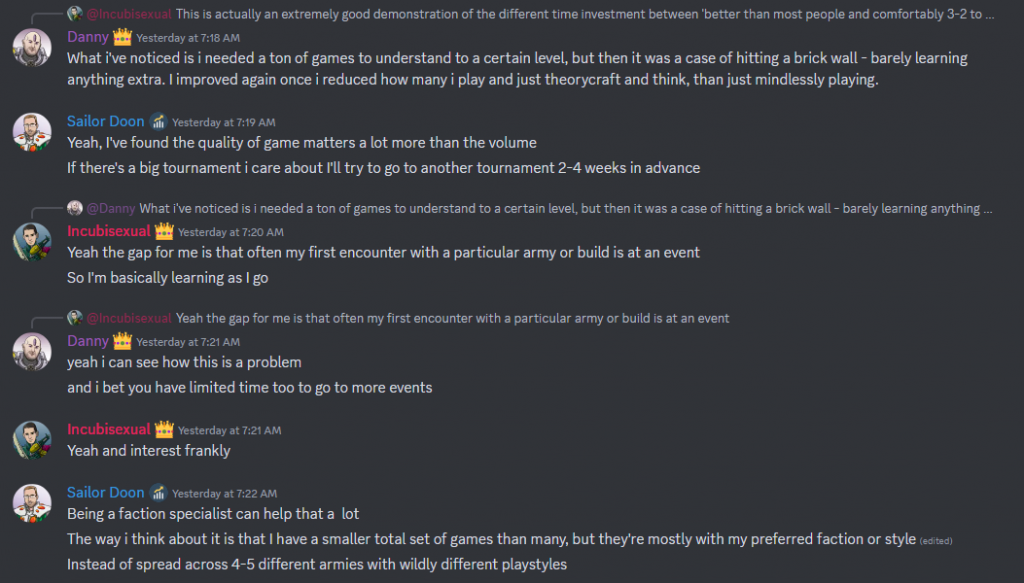

One thing our comp group tended to agree on was that the quality of games was a big deal as well, and there were things you could do to refine the process.

Playing against better players also made the mix – and the Team USA were quick to mention the training sessions they’d done – and multiple players suggested that as they improved, more games wasn’t necessarily the answer. This was particularly true for players who had more or less already achieved the level of success they wanted, and were more doing maintenance. Though it’s worth noting that while tournament games drive Elo scores, they won’t necessarily create the kinds of improvement you need – in a six-round event, it’s not uncommon for players to only play one or two difficult games, reducing their ability to create improvement.

Liam’s point about enemy armies is an interesting one – I can definitely say that the toughest games I play are when I go up against a particular army or detachment for the first time (most recently Alex MacDougall’s Vanguard Tyranids in Tampa), and while I have a pretty good idea of what most armies are capable of, my win rates are much, much higher against armies I’ve already played. So if you’re on the lower end of things and looking to improve quickly and you don’t have access to a top player, that’s certainly a good area to start – and an area where raw volume can do the job.

Practice Game Counting

One last fun exercise we can do is to talk about some of the baseline challenges in creating the ideal practice environment. Becoming an expert is in part about pattern recognition and one of the most important ways that manifests in Warhammer 40k is through playing other factions and becoming comfortable with what they can do and how your army can interact with them. Even in negative matchups, you can maximize your changes of pulling off the upset.

So how many games does that take? Well, as of this writing there are currently 28 or so factions in the game, but among those factions there may be armies with different playstyles and capabilities depending on the Detachment they’ve chosen. If we expand the list to consider detachments, we jump from 28 potential opponents to 86 – that’s an insane amount of variation, and it’s only going to grow as more codexes release!

The good news is that we can restrict the list a little bit by only looking at serious contenders. If we restrict our focus to just the detachments which had a top 4 GT showing since September 1, 2024, we end up with a more manageable 48 possible opponents.

Top 4 List Detachments since September 1, 2024 - click to expand

Still, 48 opponents is quite a lot – you’d need 48 games at a minimum to play against them all, and in an ideal scenario you’re testing with different primary missions, rules, and terrain layouts. This is a daunting enough project on its own – and something that can take the better part of a year to complete, even as those armies are changing and being updated – and that ignores the challenge of finding a skilled player to test against. It’s a very difficult task without a dedicated support structure, and often the people in that structure will be competing against you at the events you attend, and gaining a similar edge from playing against you. If you are dedicated to that madness, note that it’s going to take you around 2,400 hours to play the 960 or so games you’ll need to knock out every detachment on every Pariah Nexus Tournament Companion mission set, and that’s before you consider terrain layouts.

The good news is that I don’t think you need to log twenty games against every Detachment that scores a top 4; doing so would certainly make you a better player, sure – but you can close a lot of these gaps with study – understanding what armies are capable of, talking to good players who field them, and reading up on their matchups can go a long way to making sure you aren’t surprised. Hell, even having a five-minute conversation before a game against an unfamiliar army can be huge – I’ve frequently hit up the Goonhammer team before taking on an unfamiliar opponent to ask “what do I need to know about playing this army?”

Final Thoughts

There’s a lot to be said for the idea of setting a goal for where you want to get to competitively and then putting in the effort to get there. But equally, it’s worth being realistic about the amount of time and effort that goal will take and whether you can afford to put that effort in. Likewise, it’s OK to be satisfied (and you should be) with “good enough,” on the understanding that you’re going to come up short against people who are putting in the time and effort to surpass you. Are there ways to short-cut some of the hard work? Sure. are the top players also using those? Also yes. Regardless of where you want to end up – be it in win/loss record, painting, or sportsmanship – you’re going to have to square up with the level of work required to get there and put in the effort.

And if you decide putting in a thousand hours per year isn’t for you, that’s perfectly fine.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.