On occasion, after a bad game where one’s opponent was a little shifty with their dice and rolled a suspicious number of 6’s, you hear calls that we should all be using proper Casino-style dice in our little toy soldier games. After all, if it’s good enough for a multi-billion dollar business sector built on randomness, it’s probably good enough for someone’s Heresy Iron Warriors (because lets be honest, Perturabo would absolutely be the Primarch who insisted on using casino dice).

Seeing as generating random numbers is a major part of both my hobby and professional life, clicky math rocks are more than a passing interest, and I’ve been curious about the actual utility of precision dice, but it’s remained purely a curiosity because casino dice are absolutely heinous to use in the real world. They’re big, which makes rolling them in volumes difficult, they’re heavy and awkward, and carry a non-trivial risk of taking out someone’s lovingly converted resin model. But then Baron of Dice came out with a new set of precision dice that at a much more viable 16mm. They’re quite pretty – but do they do anything?

Methodology

There are lots of ways that people have looked at the fairness of dice, and a lot of cleverness goes into trying to isolate factors beyond the question of is a die balanced – that is, does the weight distribution of the die mean that it has an equal probability landing on each face?

I’m not going to do that, because I’m not actually interested in insulating those factors away. I want the real world messiness of dice rolling in – that I roll dice in multiples, that I roll them into a dice tray, and that there is indeed a physical act of rolling dice that takes place. So no neat little robotic mechanisms or anything like that here – just someone rolling dice into a tray five at a time, 1,000 times, for each set of dice tested, usually while on Zoom calls that could have been emails, or while rewatching Deadwood.

Dice Tested

Five different sets of dice were tested for this, to cover a broad swath of what gamers might use. They were:

- Baron of Dice Precision Dice: Obviously, as the sort of impetus to do this, these get included. I had already picked up a blue and white set, which interestingly have a slight swirl in them, which is not what I expected, as that seems like it would make said precision balancing harder. But they are very pretty…

- Games Workshop Dice: I figure a set of GW dice represents what an awful lot of people in our hobby are using, so they rate inclusion. In this case, I used the new Solar Auxilia dice, because it’s the first set I grabbed.

- Chessex Dice: Another major manufacturer of dice, specifically dice for my personal blog, Variance Hammer. These dice serve as a stand-in for blogs, podcasts, stores, etc. that have their own logo dice, from one of the easiest manufacturers to get said dice from (I wrote about the experience here a long time ago). Importantly, these are dice where, in start contrast to precision dice, absolutely zero thought has got into what the logo has done to the balance of the dice.

- Baron of Dice NOVA Dice: A set of dice from last year’s NOVA Open, representing a more premium, logo-on-the-6, non-precision dice set from Baron of Dice.

- A set of five new 3/4th of an inch, serialized casino dice from casinosupply.com to serve as a control.

Statistics

There are a lot of ways to ask the question “Is this supposedly random thing really random?”, including some very sophisticated techniques for when you think the answer might be “No”. But one of the best – and thankfully easiest ones to actually do, is what’s known as the Chi-squared test. Wikipedia has a lovely discussion of the background here, but in brief, it’s a statistical test that asks whether the observed distribution of some categorical data (in this case, the count of how many of each face came up) matches an expected distribution (in this case, 1/6th * 1000, or 166.67 for each face), within the error expected by random chance.

There is one slight twist to this – because we’re asking that question repeatedly (in this case five times), we have what’s called a multiple comparisons problem. Essentially, if we asked this question about an infinite number of sets of dice, 5% of them will be statistically significantly different from the expected distribution by random chance alone. This is a big problem if you’re doing research in genomics, but for us, it’s a somewhat smaller problem, solved by something called a Bonferonni Correction, which just means we adjust our threshold for what we consider significant downward by 0.5/N, where N is the number of comparisons. In this case, since N = 5, we consider something significant if we get a p-value of 0.01, rather than the usual 0.05. Somewhat esoteric, but it’s the kind of thing someone will get upset at me about if I don’t mention it.

Visualization

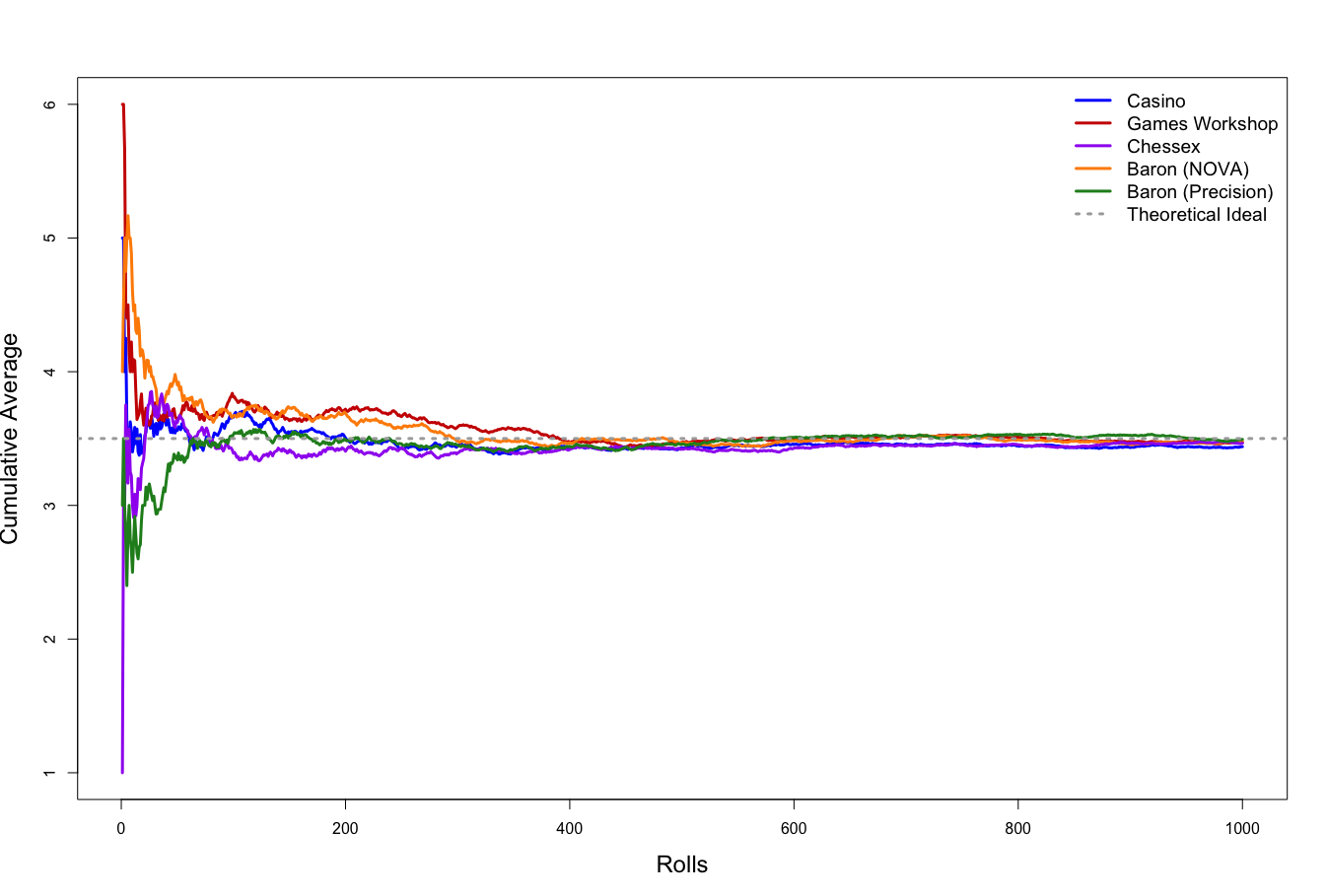

We can also look at this visually. Essentially, if we plot the cumulative average of the rolls of each set of dice, if they’re fair, they should converge to about 3.5. This is exploiting something called the Law of Large Numbers, and is essentially the basis for “math hammer” as a concept – if you roll enough times, you should have results that match the theoretical average or expectation. For this, I actually scramble the order of the rolls in each set of dice, to account for very human tendencies of mine to group the dice by number as I enter them in, which would artificially distort what we’d be looking at by producing strings of 6’s, 1’s, etc.

Why 1,000?

Because people like round numbers. And it seemed like a reasonable number to represent more than the average game, but not wildly more than the average game. That last bit is important – we could roll the dice hundreds of thousands or millions of times (at least in theory) and detect minute deviations from truly random, but in addition to probably completely destroying my wrists, that also wouldn’t reflect how the typical gamer experiences those slight deviations. Essentially…if you don’t notice it, I’m going to argue it doesn’t matter.

How’d Our Dice Do?

Dice were rolled. Many, many dice. Enough that it annoyed my wife. If you’d like to play around with them yourself, I’ve tossed them up on GitHub.

My first impression? Confirming that casino dice are absolutely not even within the realm of practicality. A useful control for this, but if the answer was “We should all be using casino dice”, my actual suggestion would be for us all to accept the lack of randomness and move on with our lives. Interestingly, they were also just hard to get to roll in a confined space, which actually reduces the amount of tumbling they did.

But are they random?

As a control, and for expectation setting, yes, our casino control dice are statistically indistinguishable from random. Specifically, the casino dice have a Chi-squared statistic of 4.772 (smaller numbers are better), and a p-value for the Chi-squared test of 0.44, meaning if we did this experiment an infinite number of times, we’d expect random chance to produce deviations from the expected perfectly random distribution of results this or more extreme 44% of the time.

The rest of this I’m just going to pop into a table.

What do we take away from all this? First, it’s sort of aesthetically pleasing that the Baron of Dice precision dice were very similar to the casino dice, but this is an artifact of randomness. In that same league was “Some random Chessex dice from someone’s blog”. Even the dice that deviated a little more from the expected distribution didn’t do so more than might be expected by random chance — recall that with the correction for asking this question multiple times, we’re looking for a p-value of 0.01, not 0.05, to be statistically significant.

Let’s look at the visual representation…

That grey line is what we’re aiming for. We start with chaos, of course. If your first die is a 6, your average is a six, and it may take some time to drag that down. And we can see that in the graph – the Games Workshop and NOVA dice roll a bit high for awhile, while the Chessex dice over-perform briefly, and then underperform, before stabilizing out. And at the end of the day, all of the dice sets are about where we’d expect them to be, very near the expected average of 3.5. If we think about this in game terms, because you’re on the left hand side of the graph for most of your games, your dice may feel hot or cold, but when it comes down to it, in the long term, they’re performing how dice should. And the precision dice don’t really arrive at that point any quicker. Functionally, when we take into account the act of rolling dice in your hand, them bouncing off each other and the walls of a dice tray, etc., enough randomness seems to be introduced to functionally offset imbalances in the dice themselves. Would that stand up before a gaming commission? Probably not. But for the purposes of your average miniatures wargame?

That’ll do pig, that’ll do.

So should you buy precision dice to make your games more fair, remove the chance for your dice to mess with you, and usher you into a new universe of gameplay?

Absolutely not.

Should you buy them because they look cool, and sometimes it’s fun to make particularly important rolls on special feeling dice?

I did.

But then again, I really do love math rocks.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.