It is my pleasure to inform you that Hades is, once again, for the second year running, my Game of the Year. Sorry, I don’t make the rules. That’s just how it is.

That’s a lie, of course. I do in fact make the rules, and even though this game has been covered in this space before, with Hades releasing out of Early Access — and onto the Nintendo eStore for the Switch, as well as the Epic Game Store and Steam where it was previously — I think there’s been both enough time passed and enough content added to the product to justify another look at it. Hades started out as a game with an incredibly tight gameplay loop without much variety or length, but still a fundamentally complete experience. It’s evolved into quite possibly the best rogue-lite ever made.

It’s perhaps a bit fitting that it’s been fully released the same week as Spelunky 2, an actual rogue-like that is basically a recapitulation and close riff on all the systems that made the original game a massive success, because the two games are fantastic examples of how to do the same genre phenomenally well in completely different ways. The difference between a “rogue-lite” and a “rogue-like” (named after the generally agreed-upon forefather of the genre, 1980’s Rogue, though arguably NetHack almost a decade later did more to popularize the genre) is found in whether or not your run-based game has a layer of meta-progression between the runs that makes subsequent runs easier the more you play. In the Spelunky games, the only form of progression that really exists outside of cosmetics and story beats are shortcuts between the biomes or “acts” of each run, and they’re not only costly to open but are in a real way trap options — the most successful Spelunky runs start on floor 1-1 and go through each floor in turn to best build up the in-run resources used to buy items (or, more realistically in high level play, increase the number of chances they run into a shopkeeper to rob). The only truly important resource you gather — money — also doubles as your score, because you can’t take any resources with you when you die.

Not so in Hades, which has seven persistent resources — Darkness, Gemstones, Skeleton Keys, Nectar, Diamonds, Ambrosia, and Titan’s Blood — that you can earn in various ways during your runs and use between runs to either progress story objectives or permanently improve the version of Zagreus in your save file. There’s even a dedicated NPC who can assist you with currency exchanges, and a couple of secondary ways to earn these resources rather than rolling them as room or boss rewards — fishing allows you to play an incredibly simple minigame in some rooms with water tiles to catch fish to convert into resources in the lounge kitchen, while the prophecies of the Fates in Zagreus’s room dole out caches of resources when the player does something like meet every Olympian god or achieve this or that story beat. Unlike Spelunky, the persistent player-character in Hades is always improving.

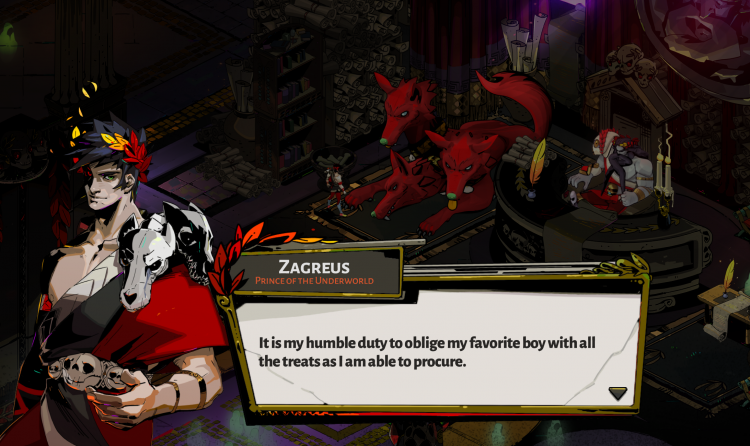

This isn’t a new concept — perhaps the most famous progression-focused rogue-lite of the past generation was Rogue Legacy, which itself recently received a sequel, and more recently Dead Cells was an excellent iteration on the rogue-lite formula, if a bit more punishing and closer to a true rogue-like than some of its forebears. What is new, and is so obvious in retrospect that people should expect to see games in this genre riffing off this concept for years to come, is the idea of making the run-based meta-progression the active focus of the game’s narrative and character structure, rather than a thin framework used as a thematic justification for the runs themselves. The extent to which Rogue Legacy was concerned with plot was “okay, your runs are descendants of a family of explorers; go to work.” The extent to which Dead Cells was concerned with plot was “okay, your runs are a weird eye inhabiting a headless body from a corpse pile; go to work.” Hades, on the other hand, is first and foremost concerned with the narrative — the escape of the Prince of Hell from his father’s Underworld — and the runs exist in service to that story. Doesn’t hurt that, again, they’re some of the tightest run-based game design you’ll ever see, but as far as the game itself is concerned, the reason you play a run is so that when you’ve completed it, one way or another, you go back to all the story NPCs in the House of Hades and talk about what just happened, with a massive array of boutique interactions constantly updating as Zagreus progresses in his quest.

One reason it’s doubtful you’ll see too many successful pretenders to Hades’s throne here, though, is that putting aside the artistic talent necessary to pull it off well…it’s just so much work. Again, Hades was in Early Access for two years, and when it launched to Early Access on the Epic Game store in late 2018 it already had a complete gameplay loop. The biggest changes to gameplay since the day one build have been the addition of the supers on the triggers, the God Gauge on RT and the summons on LT. Everything else was basically in there day one, except with fewer floors, enemies, power modifiers, and so on. Two years and over a dozen major updates were spent expanding upon and populating the world of Hades, so that, for example, when you return to the House of Hades after dying, the layabout scribe Hypnos not only has something to say for each enemy or boss that might have killed you, but usually multiple things to say for each enemy (definitely for each boss), along with things to say about all the various environmental, trap, and other situational kills it’s possible to suffer during a run. The characters with the least amount of unique dialogue — the Olympian gods themselves — still have hundreds of lines of it, at times overlapping with each other in conversations. That’s the level of dedication you have to have in order to pull this off in a run-based game after all: the player can’t hit the point where NPCs start saying one of a half-dozen generic things after all unique content has been exhausted in the first twenty, thirty, or even fifty runs. My two-year-old file in the game has gone over 100 runs and is still running into unique content, with the caveats that it was exhausting content as it was released. My brand new 1.0 file is about 20 runs in and doesn’t feel like it’s scratched the surface of stuff that both I remember seeing in some form years ago but other stuff that’s brand new.

Anyway, the Epic Store tells me I’ve played Hades now for just under a week straight accumulated over the past couple years, and I suspect however that program counts playtime it’s shading low. There are not enough good things to say about it; the last one relevant to those who might have been turned off by previous Supergiant Games releases Transistor and Pyre is that rather than being boutique releases with limited appeal like those two games, Hades is a big, broad game with mass-market appeal about clearing rooms full of enemies at a healthy but never rushed or frenetic pace (unless you decide to speedrun it). It is Bastion’s superior in every regard except for the soundtrack, and even there it gets pretty close. And given the response its received on launch — already surpassing a million lifetime sales — it seems very likely that Hades will find its way onto the same “games of the decade” and “games of the generation” lists that Bastion has and will.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have five more hours set aside to spend with Coronacht, the Heart-Seeking Bow, which I derided as trash-tier during Early Access but now realize might be the best weapon in the game.

Final Verdict:

I thought it was a steal at $25 when it released at that price point on Steam; it’s down to $20 there (the Switch version is still $25, which would be less annoying if there weren’t also stories of gamebreaking bugs currently needing to be ironed out in it). I personally would pay $60 for this game and I think with the amount of content in it you could reasonably argue it should be at the $40 price point, so any way you cut it, you’re getting a great deal on one of the best games of the past couple years.