Armoured Clash is the newest entry in Warcradle Studios’ Dystopian Age line of wargames, following Dystopian Wars and Wild West Exodus. It’s a 10mm scale combined arms wargame, featuring infantry, flying units, big tanks and bigger land ships, the conventional land army equivalent to Dystopian Wars’ naval combat.

I had the privilege to speak to James M Hewitt, Warcradle Studios’ Lead Game Designer about the game, his approach to working on it, and what exactly makes 10mm gaming cool in the first place.

Goonhammer: Last time we had you on was to talk about Modiphius’s Fallout Factions, and now you’re over at Warcradle Studios. How has the transition been and what are you up to these days?

James: It’s been really smooth! Due to the nature of game production timelines, there are a lot of things that Sophie [Williams, long-time game design partner-in-crime] and I worked on at Modiphius that will probably be coming out over the next year or so. Lots of stuff for Factions, but also some other interesting things. We’ve kept in touch with the Modiphius dev team, and it sounds like things are going really well over there.

But yeah, we’ve been at Warcradle for about three months now, and we’ve really hit the ground running. Our new team is off to a flying start – the first thing we’ve been focusing on, unsurprisingly, is Armoured Clash. The core design had already been done by the time we started, so we were able to focus on development, testing and fine tuning… and most importantly, writing the rulebook. That’s been a labour of love, and I can’t wait to see what people think of it.

GH: What makes the rulebook a labor of love?

James: So, for context, when you’re designing a game, you need to break things into stages. In the broadest sense, you’ve got three big chunks: core design (building the “engine” of the game), development (polishing the engine and adding to it to complete the game from a mechanical perspective) and rules writing. They’re all separate and distinct, and have to happen in that order. When we’re designing a game, during the design and development stage, there are still written rules – but they’re scrappy and unpolished, with the main purpose of codifying the rules, i.e. having them all written down so you can keep track of them.

The rules writing stage is all about rewriting from the ground up to create a rulebook that teaches the game, while also acting as a reference for players to use during a game. Good rulebooks are ones that manage to pull off that balancing act, which is never easy, because a teaching manual and a clear reference are two very different things, with a lot of needs that are in direct opposition with each other.

So with Armoured Clash, we really wanted to make a statement. This is a new game from Warcradle, it’s the first thing we’re doing here… let’s go all out, and show the wargaming community that, hey, this is what we think a rulebook should look like. It’s a statement of intent, as much as anything – this is the minimum standard we’re setting for everything we do from now on.

I can’t tell you how proud I am of this rulebook, and all the work the dev team has put into it. (Not to mention the graphics and artwork – it’s really been a team effort!) The whole dev team has been involved in compiling the rules, figuring out the order in which they should be presented, settling on formatting conventions, checking (and rechecking, and rechecking again) page references, captions and boxouts.

Let’s just say that when it went to print, we all went out for a slap-up meal to celebrate, and it was very well earned!

GH: How would you describe how Armoured Clash plays?

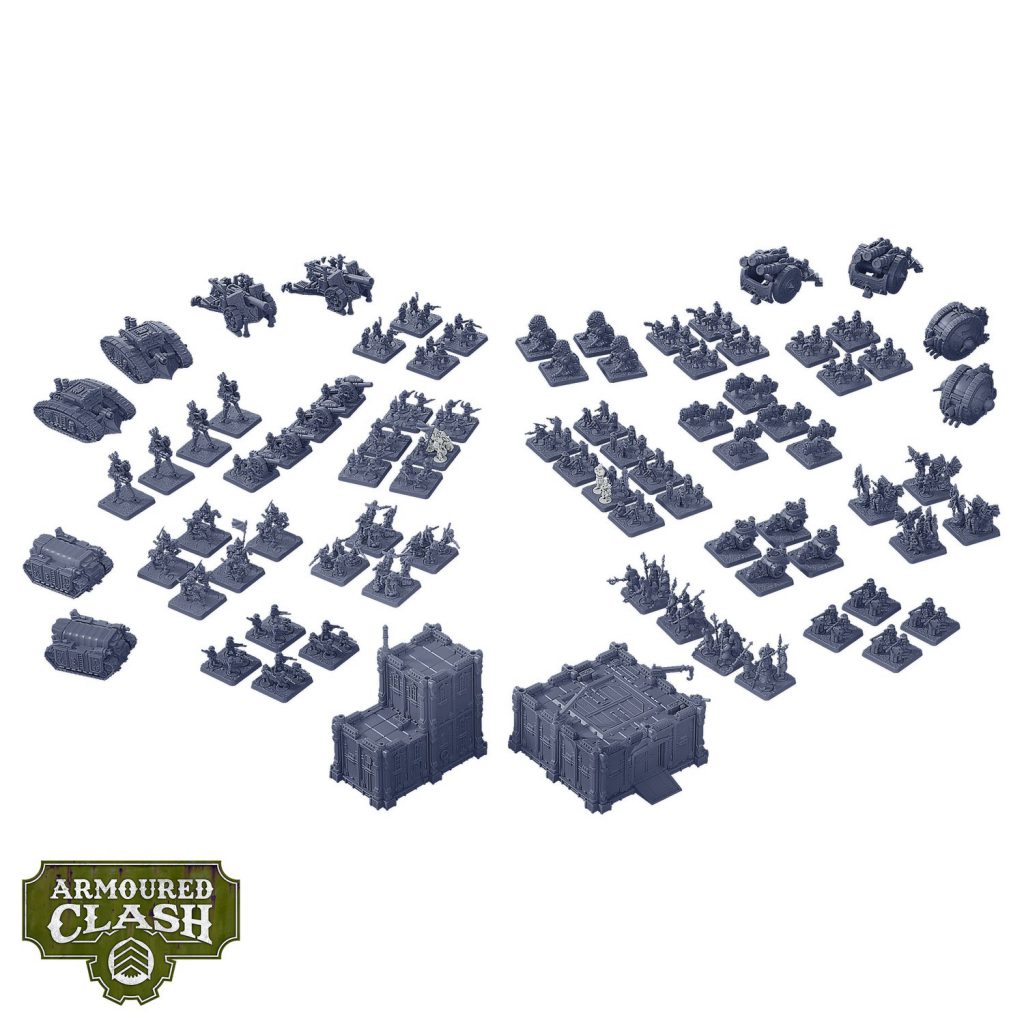

James: In Armoured Clash, each player (or General, as we call them in the rules!) commands a Force made up of multiple units, all drawn from a single Faction. The units are all designed around the miniatures – for example, a basic-strength Crown Rifles Platoon has six models (i.e. six stands of four soldiers) because that’s what’s on the sprue. The vast majority of units (pretty much anything in plastic) can be reinforced by adding a second or third sprue’s worth of models, so to continue the example, a reinforced Crown Rifles Platoon is twelve models, and a full-strength one is eighteen.

All of the units in your force are arranged into Battlegroups. These are organisational units, which mainly come into play when you’re assembling your Force, ensuring that you have a sensible balance of units (and you’re not just turning up with half a dozen Sovereign Landships).

Each game uses a scenario (what we call a Clash), which is pretty much what you’d expect – deployment instructions, objectives, special rules, and so on. The Clashes in the rulebook are intended to offer simple, more-or-less balanced games, but down the line we’ve got all sorts of ideas for interesting scenarios.

Most Clashes last for five Rounds. On a Round, players take turns Activating a unit – this generally means moving it and then attacking with it, although there are of course loads of interesting wrinkles. Once all of the units on the battlefield have been activated, the Round ends and a new one begins.

Any attacks are resolved with custom six-sided dice, and I’m quite fond of how simple-but-deep the attack system is. Each unit in the game has a Target Category – Light (infantry, cavalry, smaller field guns – more or less anything on a square base), Heavy (tanks, artillery, fortifications, etc) and Aerial (aircraft, rotorcraft, anything that’s up in the sky). And then, each unit has a number of different Attacks on its profile (usually two or three), each one of which corresponds to a different Target Category. So you’re not concerning yourself with the specific weapons that are being used (we’re far too zoomed-out for that!), but rather with how effective your unit is against a specific type of target.

So you look up the relevant attack on your unit profile, you grab the number of dice that corresponds with the number of models in the attacking unit, and you roll them. Then, you’ll get to re-roll some dice that fail – more if you’ve put yourself in a strong position – and move on to dishing out hits. We’ve found that by the second or third round, a new player is resolving an attack in under a minute. That’s fantastic, because again, this game’s about big armies with lots of units, so you don’t want to be getting bogged down with loads of resolution steps for every single attack.

That’s not to say things are dull or straightforward, though. I’ve always been a big believer in giving players lots of juicy decisions, and that’s definitely the case here. A shrewd player has a lot to think about – and that’s before you include Command & Conquest cards. There’s a real feeling of “combined arms” strategy, especially with the way that Target Categories work. A unit that’s great at killing tanks might be terrible at taking out infantry, so to win a game you really need to think in terms of your entire force, not just individual killer units.

GH: What’s your favorite rule in Armoured Clash?

James: That’s a tricky one, there are a few favourites – I like how streamlined the dice mechanic is, for a start. But I think I’m gonna go with Communications Breakdown.

For context, each player has their own deck of Command & Conquest cards. If you’ve played Dystopian Wars, it’ll seem familiar – you draw a hand at the start of each round, and you can play them during the round to issue Commands (letting your units bend the rules, and gaining little buffs) or claim Conquest Objectives (scoring some Victory Points). Each card has a Command and a Conquest Objective on it, so there’s always an element of having to choose between the two parts of the card, and deciding when to seize the opportunity.

On top of that, the cards are also marked with a value from 1 to 12 (five of each in the deck, for the stats fans out there), and whenever you need to take a Discipline Test for one of your units (to prevent it being Suppressed by enemy fire, for example) you draw the top card of your deck, and compare its value to the unit’s Discipline value. If the card is higher, you fail.

So, straight away, we’re using the deck for a couple of different things. But here’s where it gets really interesting:

If your deck runs out during a game, you reshuffle your discard pile to create a new one… but this represents a Communications Breakdown. You’ve over-extended yourself, and for the rest of the game, you don’t draw any cards into your hand – you only use your deck for Discipline tests. And if your opponent’s been more cautious, that means they’re going to suddenly have a lot of options that you don’t.

So suddenly, there’s an extra level to the decision space. The more cards you play in a round, the more you’re gonna draw to replenish your hand, the sooner you’re gonna hit that point of breakdown. Also, before you draw at the start of a round, you can discard as many cards as you like. Seems like a no-brainer if the ones in your hand aren’t lining up with what you want… but, again, you’re just accelerating towards your own downfall. And another thing – whenever you need to take a Discipline Test, you can instead choose to not draw a card, and automatically fail. That really sucks in the short term, but it might make all the difference when your deck’s running low.

In short (ha!) I feel like we’ve really managed to make the deck integral to the game. It’s a nice bit of “slippage” between your intentions and what actually happens, which is something I love to include in games that represent conflict on this sort of scale.

GH: Was there anything you wanted to make work but had to cut?

James: Well, first of all, a good rule is never cut – it just gets set aside for the future! (Admittedly, it might end up in a different game entirely… but still, no good rule is never lost.) That said, I’m a fervent believer in taking a chainsaw to your darlings, so a big chunk of our time on Armoured Clash was spent questioning whether rules could justify their place in the rulebook. Is this worth keeping? Could we trim it? This adds a fair bit of complexity, what happens if we remove it? So yeah, I’ve got no regrets – I think we cut everything that needed cutting, but we weren’t over-zealous.

And of course, a lot of what we trimmed was immediately repurposed – some of it became unit special rules or weapon qualities, some became special commands, some of it is destined for scenario rules or campaign bonuses. Some rejected rules might even jump to other systems, so I’m gonna keep quiet on what we cut, just to avoid spoiling anything.

GH: With Armoured Clash bringing in unit types we’ve never seen in the Dystopian Age line before, how does the team balance expanding a faction’s identity with making them recognizable in playstyle and aesthetics to the Dystopian Wars version?

James: It’s a great question, and one that I can only give a limited answer to – so far, I’ve mostly been involved in writing rules for miniatures that have already been designed and sculpted.

One of the advantages with the Dystopian Age, compared to other settings, is that it’s almost historical. It’s not quite, but it’s close… so there’s an awful lot of source material to draw on. I know there are certain miniatures in the range that are based on designs that never quite made it to the front lines in the real world – and I love that idea. For whatever reason, something didn’t work out in our world, but in this alternate reality, it did! Maybe they had access to technology we didn’t, or maybe there was something weird and esoteric going on, or maybe it was just a “Sliding Doors” situation, and the only difference is that someone opted for Design A rather than Design B. (I think it’s important to reference obscure British romantic comedies from nearly thirty years ago. It keeps me relevant.)

So yeah, when it comes to designing a faction, there’s this whole wealth of material to draw on, and we’ve got some real history buffs on the team, people who are able to quote obscure facts and give detailed descriptions of the most unusual things. But also, the designers are thinking in terms of faction identity. One of the downsides of being history-adjacent is that, well, it’s not exactly rock-monsters and squid-people and big blobby aliens, you know? If you’ve got a fantasy or sci-fi setting, you’re making up your setting from whole cloth, and you can design your factions in a way that they’re immediately distinct at tabletop scale. Whereas in history, well, it’s all humans, and although there are differences in weapons and uniforms… you sort of lose a lot of that when they’re 10mm tall. So there’s a lot of thought about what not to include from history, and that leaves some gaps into which some madcap creativity can be poured.

When it comes to comparing a faction in Armoured Clash with the same faction in Dystopian Wars, it’s something that we’ve not been overly concerned with, because historically, a nation’s army and navy can really be quite different – and they’re very different games! But there are definitely elements that cross over. Sometimes that’s visual – for example, the Galahad tanks fielded by the Crown have very prominent armoured prows, which reflect the ones on the Crown ships in Dystopian Wars – and sometimes it’s thematic or mechanical, like how the Empire make use of fire and alchemical weapons in both games.

GH: For people who haven’t played a game in smaller than 28mm scale before, what do you think it brings to the experience of wargaming?

James: A sense of grand strategy, and the feeling of being in charge of a really big force. It’s not my first time working on a game with small-scale minis, and I think the thing that really makes it stand out is the player feeling one step removed from the action. The more you zoom out, the less you want the player to be thinking about individual soldiers. Here, the camera pulls right back, and the tabletop represents a much bigger battlefield, so you’re thinking in terms of multiple units at a time, and how they’re supporting each other.

If you’re used to wargames that are more zoomed-in, you might have to adjust to some of the abstractions that we’ve used, but they’re absolutely vital if you want to depict a battle on this scale without having to spend several hours on each turn. After a lot of testing and development, I think we’ve nailed the balance – it really does make you feel like you’re a General, safely ensconced far from the action, glaring at a map in a room full of runners and advisors.

GH: Anything else you’d like to tell our readers?

James: We’ve gone out of our way to make sure this game is a really solid entry point to 10mm scale wargaming, to the Dystopian Age setting, and even to wargaming in general! If you’ve got a friend who you’ve been trying to convince to give tabletop wargames a try, you could do a lot worse than splitting the Battle for Singapore two-player introductory set with them, and showing them the ropes. We’ve shown the game to a lot of non-gamers, and I think I can safely say that it’s turned a fair few of them into hobbyists…

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.