I might have ended last time on a down beat note, but with the world thoroughly left in tatters after Alien, Drug, and Climate breakdown apocalypses, we have finally broken through into the much more fun and light-filled world of the post-apocalypse, and Goonhammer Reads Science Fiction can take a deep breath, emerge from the vault and crack into one of the all-time staples of the SF genre.

If there’s a single theme or sub-genre that gets Scifi out into the wider world more than any other, it’s an exploration of life after the apocalypse. It doesn’t really matter what that apocalypse is, because the details rarely matter after the fact. Post-apocalyptic fiction finds its way into poetry, children’s books, “mainstream” fiction, pop-science and self-help, guidebooks, travel writing and every other genre you could expect to find outside of the rapidly shrinking section of your local bookshop marked Fantasy/Science Fiction. Wherever it ends up, though, it’s the real essence of what Science Fiction does best – telling us something about today through the lens of an imagined future. Post-apocalyptic novels see writers (and characters) forging new worlds from the ashes of the old, and the best of them transcend the oh-look-a-reference-to-our-world archaeology of injoke and nostalgia to present new ways of looking at the world. That can be through the exploration of the emptiness of militarism and madness of nuclear war in This is the Way the World Ends, exploring what it means to be a Saxon in a Norman world as in The Wake, or meditations on gender roles as in The Gate to Women’s Country. It’s such a staple of Scifi and done extremely well very often that it was a real struggle to narrow this down to our traditional three-and-a-black-library structure, leaving out dozens of books that could have fit in. The three that I’ve chosen end up looking at how Scifi has changed it’s approach to the post-apocalyptic world over the three formative decades of Scifi – the 50s, 60s and 70s.

A Canticle for Leibowitz, Walter Miller

After a devastating Nuclear War, mankind has retraced the path from survival in a scorched world into a neo-medieval world where apocalyptic horror has deeply scarred the psyche of the survivors, leaving an ingrained distrust and hatred of scientific knowledge. The last keepers of the flame of literacy are the Albertian Order of Leibowitz, a religious order in what was once New Mexico, the monks there painstakingly copying blueprints, technical manuals and scientific minutia in the light of flickering candles and dying hope.

It’s a classic, you knew it would be in here as soon as you saw it was post-apocalyptic, and the likelihood is you’ve already read it. Canticle for Leibowitz is the gold star for post-apocalyptic scifi, doing everything you’d expect and more, as well as being a cracking example of late 50s scifi that’s certainly Golden Age, but straining towards the New Wave. It’s a fix-up novel, one stitched together out of short stories published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, spanning a thousand years of history for the Order of Leibowitz as the world crawls out of Miller’s approximation of the European Monastic system, into a Renaissance and back into Modernity. There are lots of fix-ups that don’t quite gel, but this one really does, threading theme, character and reference through the centuries to build up a deep and wide world recovering, sometimes agonisingly slowly, from nuclear horror.

It’s often cited as the single best Science Fiction novel – which I disagree with because that title only belongs to one book – but whether it’s the best or not is unimportant. What it is is a fantastic example of scifi at its well written, compelling, interesting, challenging and significant best. For a novel written in the 1950s, it’s very forward-looking into what science fiction would become over the course of the next several decades, and I think if told it was written in the 1960s or 70s, you’d believe it. The only caveat – and with 50s scifi there’s usually a caveat – is that it plays around with some problematic concepts – the “Wandering Jew” of Medieval European Antisemitism. It’s there, hinted at (fairly strongly, but then I missed the reference the first time or two) and, on reflection, it’s an uncomfortable bit of medieval legend through the novel.

One of the best things about Canticle is how many other things – books, movies, tv shows, podcasts, video games, whatever – crib bits from it openly and happily. Even if you haven’t read it, you’ll find the first sections at least familiar. It’s been there for you, lurking, on the edge of your consciousness. Time to pick it up – and for the rest of us, time to give it the re-read it deserves.

Of Men and Monsters, William Tenn

Eric is a thief and a hunter, setting out on his manhood ceremony amongst the ruins of the world his species once ruled. He, and everyone he has ever known, live in the gaps and crevices in the walls of mighty fortresses, human vermin spoiling the easy lives of Earth’s new masters. The dream of all men and women is that one day they can rise again to their former glory – but when Monsters are Men and Men are Mice, what hope can there be?

From a novel that reaches forward stylistically as much as it does in the plot, to one that resolutely reaches back into an older tradition of scifi. Of Men and Monsters is classic scifi-as-adventure-story stuff, taking fantasy tropes in an almost Dungeons and Dragons adjacent style into a relatively light, ripping adventure yarn with a firmly science fiction concept. As an adventure story, Of Men and Monsters hews closely to the structures and rhythms of the hero’s journey rooted around the post-apocalyptic society of Mankind as their schism between traditionalists and reformers endangers their existence living as the vermin inside an alien world. The conventions of the post apocalypse are all there, but given surprisingly modern twists and subverted in interesting ways. You could approach it purely as adventure, but that’s not the fun thing about it.

While Of Men and Monsters is not particularly thought provoking or challenging, or even outstandingly memorable, it is an exceptionally good example of light, open, comedic science fiction. William Tenn made his name writing this kind of thing – a short story with a great premise and a humorous twist, or in pointed, targeted satire of the tropes other writers of his time over-used. Satire isn’t uncommon in Scifi, but light satire, the kind that doesn’t smack you over the face with the clarky-cat bat, is rarely done well. Tenn’s Mankind and their rodent-like existence pokes fun at a lot of our world, as well as playing with the tropes of the stock scifi “shrinking man” story. There’s always quite a bit of humour in the idea of miniscule humans trying to manage big things, but Tenn dips into that well sparingly, so the whole book remains quite humorous without becoming slapstick. It’s a short read, and you might want to save it as a palate cleanser for the next recommend.

Walk to the End of the World, Suzy McKee Charnas

Content warning for this book: Misogyny, Sexual Assault, Child Abuse, Racism

The Holdfast is the last remnant of Civilisation in a world destroyed by Nuclear Fire. The Men of the Holdfast have turned to their sole remaining resource – the bodies and labour of women – in order to rebuild militarist society. A rigid patriarchy holds the remains of the world in its grasp, and for the Fems of the Holdfast, hope is a distant, dead thing. Only the legendary Free Fems hold a last guttering light for those trapped within the monstrous grip of the Seniors.

While Canticle and Men and Monsters show challenging and funny views of the Post-Apocalyptic world respectively, Walk to the End of the World throws us into the full terrifying potential of a world destroyed and remade in horror. Charnas’ post-apocalypse is a world where misogyny is taken to it’s fullest extent, far, far beyond that in another classic feminist post-apocalyptic SF, Handmaid’s Tale. Women here are a subjugated class – the hated “Fems” – who are treated as a combination of breeding stock, slave labour and food source, living in conditions I struggle to describe but Charnas does all too well. As a post-apocalyptic novel, it’s as bad as anything can get, much more horrifying (and, distressingly, just on the edge of believability) than the worst elements of The Road. The world that men have created is monstrous, and in exploring it, we are told monstrous things. It’s not a pleasant read, and it’s not trying to be – a great example of the kind of harsh light thrown on gender and sex through scifi in the 1970s.

It’s unquestionably a dirty, gritty, angry book – and it should be. It’s an expression of radical 70’s Women’s Liberation feminism, of the long, drawn-out end of the Vietnam War, US racism and discrimination and the still-looming spectre of Mutually Assured Destruction. It puts up the question – well, the pretty-much-dead-on-prediction – “what would happen when the men responsible for the apocalypse pin the blame on women?” and then runs with that to attack the cruelty of personal and structural misogyny. We’re taken through how the society of the Holdfast operates through the eyes of male dissidents and Alledera, a female slave balancing desire for connection with Free Female enclaves and a need for destructive revenge. It’s a tense, uncomfortable and occasionally outright disgusting read that does what it sets out to do very well – winning a James Tiptree Jnr/Otherwise award (retrospectively) as a result.

I’ve recommended this one, even though it’s a troubling book, for a couple of reasons. First off is that Charnas struggled to get it published – allegedly even receiving the feedback (regarding the sequel) that it was only publishable with all female characters changed to male, which is just pretty baffling. Secondly, that the male characters are, for the most part, incredibly one dimensional – emotional eunuchs castrated by the most toxic masculinity ever put to print. As a result, it has a series of absolutely comical 1 star reviews on virtually every review site made by men who describe it as “a pointless book, seething with rage”. So, in a grand gesture of “fuck you” to all those men, I’m going to recommend you read it – it is undeniably a classic example of this corner of SF.

The sequels – Motherlines, The Furies, and Conqueror’s Child – get much weirder and tip fully into 1970s permissive society sexual stuff and I can’t honestly recommend them (I also hate horses and they feature heavily). It’s got a lot of questionable themes and actions, mostly, but not entirely, carried out by the bad guys – and seriously, heed the content warning. It’s not a nice read.

Black Library Pick

You could – fairly – argue that all Warhammer 40k fiction is post-apocalyptic. In fact, it’s post-apocalypses, 38 thousand years of society-ending disasters on multiple worlds. Our Black Library Pick this time round manages to show us one post apocalyptic society undergoing another apocalypse, which is one of those concepts you can only really do in science fiction.

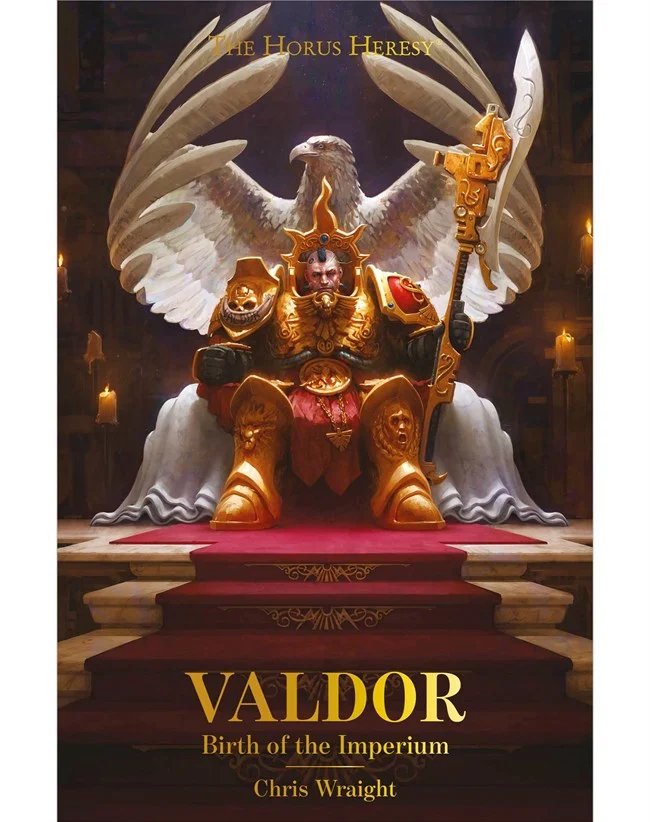

Valdor, Birth of the Imperium – Chris Wraight

The Horus Heresy character novels have been a bit of a mixed bunch really, but Valdor stands out to me as the best of the lot. It’s about the death of a dream and the slow awakening of a new nightmarish reality, pride, power and loyalty, and is most certainly post-apocalyptic. As the Unification Wars end and the Emperor sets aside his council and allies in favour of the results of his bioengineering weapons program, Wraight takes us straight through the last gasp of freedom on Terra before it’s smothered under the relentless march of power armoured boots. It’s written in his usual extremely competent, exciting and atmospheric manner, something that’s marked every single one of Wraight’s books for the Black Library out since he started off with short stories in the early 2010s.

It’s a really interesting, worthwhile read on a couple of fronts. It’s the earliest we’ve seen the Imperium and the 30/40k setting so far outside of scattered flashbacks and historical references. This truly is the birth of the Imperium and the death of it’s first enemies, so as an insight into what was happening on Terra it’s invaluable. More than that though, there are many little threads of connection to 30k and 40k stories that – if you squint in the right light and hold your head in a certain way – you can convince yourself that the Black Library is opening on some universe-shattering secrets just around the corner. Reading it with Abnett’s The End and the Death, Pariah and Penitent with Chris Wraight’s Vaults of Terra and Watchers of the Throne series all in mind and something is happening to the 40k Universe. Something with the Custodes at the heart of it. Something that appears, you might say, to be apocalyptic in scale.

Next time: Itopia? Why don’t Youtopia?

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Expecting a quick comment about Heinlein and disappointed to find I’ve run out of ideas in that direction? Get in touch with us at contact@goonhammer.com, or leave a comment below and join our Patreon and talk about books, please!