On the weekend of the 29th and 30th October 2022 the Goonhammer Open UK ran and one of the events we put on was The Siege of Vandia, a narrative campaign for Horus Heresy. In this second of two articles covering the event, Lupe takes a look at the details of how the campaign worked behind the scenes, what worked and what didn’t, and where to go from here.

If you haven’t checked out part one you absolutely should because it’s where all the fun narrative stuff and beautiful sweeping photos are. Here you’ll find, instead, some much worse photos (taken by me rather than the talented Soggy) alongside some lovely ones, and a lot of chat about just what running a narrative event means to me and how I made it (mostly) work.

What is a narrative anyway?

One of the things that struck me coming away from the weekend was I had several players tell me excitedly how cool they thought the narrative was because there was a story and their actions impacted it. Which is honestly a surreal thing to hear because what is a narrative otherwise?

Well, that’s a good question as a it turns out, and while a lot of people absolutely run narrative events in similar ways to how I did, quite a few “narrative events” aren’t like this. Instead “narrative” is used as a way to say “not competitive” or even “not a formal swiss pairing tournament” and honestly that’s surreal to me, but here we are. I knew from the get go I wanted a narrative event and that meant:

- A setting and background for the story to unfold in

- A narrative arc that the players could impact

- Narrative rewards and twists that could be unlocked through certain actions

- A number of different endings to be decided between

What is this narrative anyway?

I had a chat with Soggy about the Titanicus narrative and we decided given the time restraints a fully connected campaign wasn’t going to be feasible this time round, but I put a moon (Vandia) in orbit around the setting of his campaign (Tyras III) as the focus of mine. Just as the Traitors would be assaulting Tyras III below, they would be assaulting Vandia above.

One of the first things that jumped out to me was to explain why there weren’t titans wandering around – if there were titans nearby why couldn’t they land? From that question arose the Vandia Defensive Array, the macrobatteries that would blast ships that stayed in orbit too long to pieces. This also gave me a way to make this a bit fairer on the factions in the background – the Traitors would have a certain number of troops dropped, and the Loyalists would have a certain number of defenders already in place. Relatively evenly matched, things could remain plausibly tense as the campaign wore on.

Given the opportunity to run an event over two days I knew immediately I wanted to run it across two in game days as well – it’s too cool not to do. But that raises the question of what happens when those two days run out, and why is that the end no matter which way the campaign goes? The answer was the loyalist relief fleet, and the need to seize those defence guns before it arrived.

With that decided I had the roughly outline of the narrative: Vandia was a hive moon which would be besieged/assaulted by traitor forces who could only land in limited numbers, and which had two days to take the macrobatteries and turn the guns on the loyalist relief fleet.

Trees and branches

The classic campaign structure is a tree design – each decision allows for the narrative to divide onto several different branches, and those branches in turn split into branches of their own. This is great in that every single decision point (games in a wargaming event for the most part, but sometimes strategic decisions made by commanders outside of games) results in a unique and interesting path but there are a few big downsides. Prep is the biggest: you’re preparing a huge number of different outcomes, the vast majority of which will never be used.

So the model I ended up with for this campaign was a “limited tree” campaign. It would be made up of a number of decision points, one after each game, that pushed the narrative one way or the other, but those decisions wouldn’t be the outcome of a single decision, but of all the cumulative decisions to date in the campaign. On top of that each decision point would be fixed – no matter which way things went the campaign would still broadly follow the same arc, just with differences thrown up from the decision points.

To achieve this I sketched out a rough arc of the narrative: the traitors would land on the Galan Plains, advanced towards the Shield Wall of Hive Primus, breach the wall and then enter the hive before advancing towards the macrobattery control centre. This would happen regardless, and knowing it needed to I went back and tweaked the setup a little. No longer were the factions evenly matched in lore, but instead the traitors had the distinct advantage.

The outcomes of the decision were no longer “can the loyalists stop the traitors at the wall” but instead “how much can they make them pay for it, how much can they slow them down, and how much can they hurt their future prospects”. This allowed the relief fleet to be the deciding factor one way or the other, with the real outcome being what happens when they arrive – in truth the whole campaign came down to a single binary choice: did the traitors hold the batteries, or the loyalists?

To calculate the progress of the factions I created a system of Campaign Victory Points. I could have just used the Victory Points achieved in each game, but the Heresy Core Book missions have some serious swing to them and I’m very glad I didn’t just use the VP results. We had a bunch of games where the CVP (measuring success but also how robust your forces are to carry on fighting) was very even or close, but the VP scores were wildly different. Games that resulted in a 17-0 VP score could (and did) result in a 1-1 CVP score. Ultimately the VP outcomes don’t match the overall performance of the players, and that’s a weakness of the missions.

So now we have a rough map of how the “tree” will work: each game will result in CVP for each allegiance, which feeds into a running total for both sides. Whichever side is ahead after each game wins that “decision point” and the narrative moves to their advantage.

Practically what that meant was some different narrative descriptions in the pre-game briefings, and also some minor bonuses or benefits for the different allegiances going into the next game. So in one game if the Traitors were ahead they automatically won the roll-off to go first, but if the Loyalists had been ahead they would have done instead.

Levers to pull

But that doesn’t feel like enough levers to pull to me – sure there are some outcomes here and there, but I wanted the players to feel fully in control of their destiny in what was, in truth, a very limited number of outcomes. I therefore came up with a few more narrative levers to pull.

The first was Honour. Each independent character (with a name, very important) won an Honour for each game they survived. This honour could be spent for a one-off buff (an extra reaction) in any future game, or one making use of narrative benefits won by the allegiance.

And narrative benefits is the real thing that I wanted to bring to the forefront. Getting people invested in the outcome of the event often involves making them feel like the players themselves are getting to make meaningful decisions, and narrative benefits that they can choose when to use are great for this. It gives players power over outcomes, not just because they’re making a decision, but because those decisions influence the outcome of the major decision points (games).

But coordinating 12 players on each side (we sold 24 tickets originally, with 22 players actually making it to the event – a pretty decent drop out rate) to do this is hard, so I needed a way to make it easier. The answer, of course, was democracy, the best way to diffuse responsibility and make people feel involved even if they’re not actually getting a say.

I decided to have allegiances elect a Supreme Commander. This SC would choose which players would attempt Special Operations to win narrative rewards (basically extra objectives in their existing games to make their job harder) and also which game to spend narrative rewards on (as they can only be chosen for one mission). Players then get to choose whether to receive the benefits of the narrative reward by spending one of their Honour.

I chose this system for a few reasons:

- it actually only meant really interacting with and requiring the decisions of one player for allegiance, making it all a lot easier to run on the day

- by having the players elect the supreme commander (and remove them if they wanted to, which the traitors did after every game) that gave all the players a sense of making a decision even if I was actually only talking to one player

- by having that supreme commander appoint players to attempt special missions it gave everyone a sense of narrative impact (I turned up to each player affected and said “General, your Supreme Commander has assigned you a special mission for you to complete” and people reacted super well to this) and also a sense of responsibility and control. If I’d picked those people it would be Event Organiser fiat, but by having the SC do it they had a control mechanism – they could remove them from power

- Honour would allow factions that didn’t manage to win their narrative rewards to do something else with the resource, and allow people who didn’t want the narrative reward to still have something valuable

The battlefield is chosen

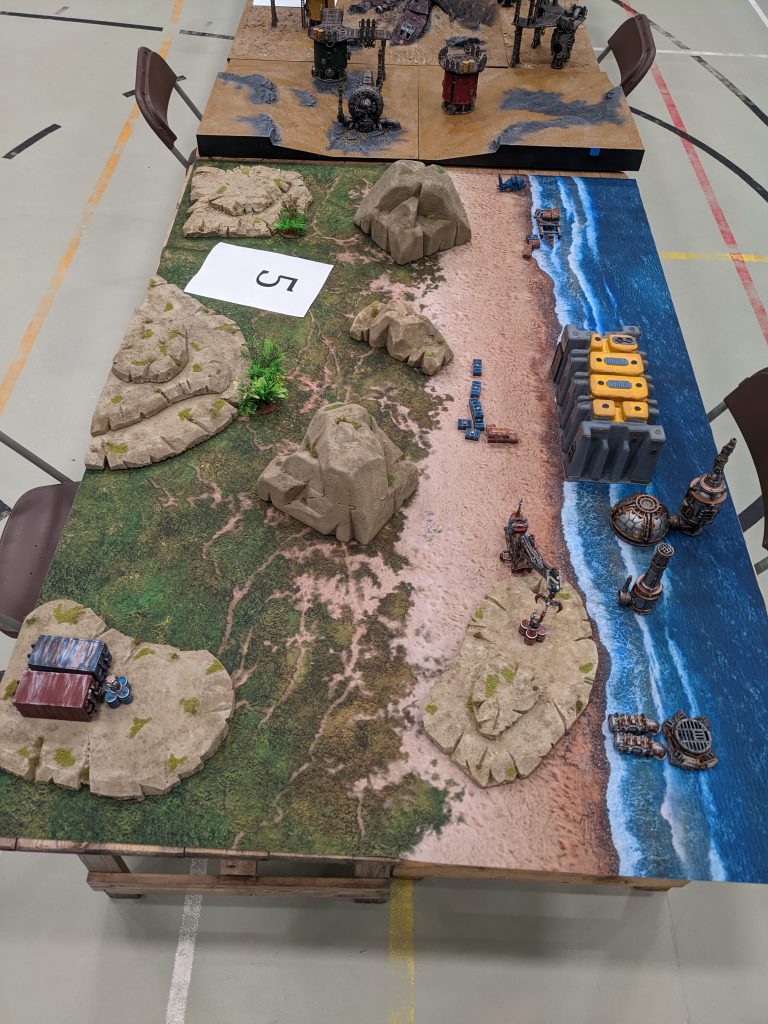

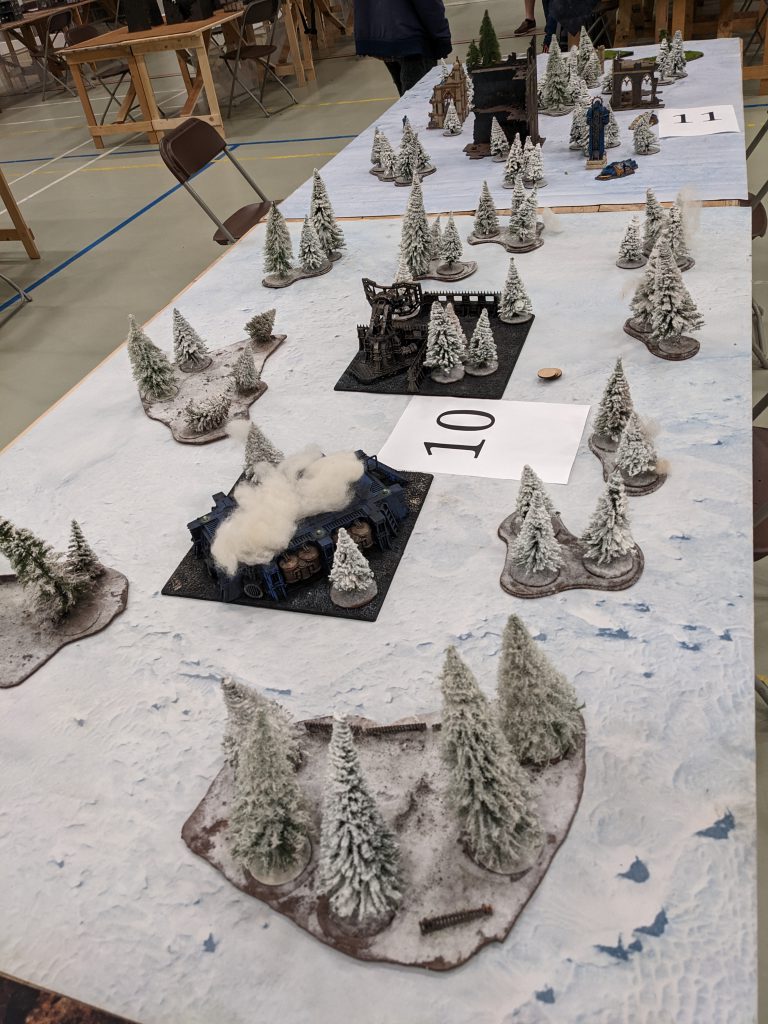

We arrived at the venue at about 4pm on Friday evening and got tables laid out and set up, and then the terrain arrived. I’d put the call out for as much terrain as possible to be sent up and lots of people pitched in to do this. We had a huge number of people loan things, and Factorum also provided some big boxes of narrative terrain which I was enormously grateful for.

When it arrived it quickly became clear the way forward was themed tables so we did some jungle tables, some city tables, some winter tables and so on. The Galan Plains are a big old place, that’s just how things look, you see.

I came to the weekend with two plans: one for if we ended up with a lot of city type terrain (which is what the standard Factorum boxes are) and one for if we had a lot of mixed terrain. We ended up with the latter so for the sake of ease these tables were used across the whole weekend. My plan was, if we were playing on city tables, to shift things around and mix up the terrain a bit after day one, but there just wasn’t the time, terrain or need to do that on such varied tables.

Problems of pairing

I went into the event with the intention of using a swiss pairing (pairing the best performing players together) and this is what I did for round two, but this turned out to be a mistake. I had hand paired the first round to ensure as good games as possible given the available armies, and that went well, but it meant that the big scoring games were where people got lucky or where I’d misjudged the match up for the most part, not because someone was a better player or had a stronger army. This meant going into round two we had some rough match ups, and as such after that round I abandoned swiss and just paired randomly, trying to avoid repeat match ups as much as possible.

I wasn’t always successful in that, especially when on the Sunday we had a number of drops that caused players to need to be matched together differently. In addition the final game I’d given people the option to play either a 3k or a doubles, and that caused no end of issues. In future I’d:

- use a random pairing tool rather than trying to do my swiss method, having to abandon it, and then end up pairing by hand

- just run two doubles rounds and not include a 3000 point option, because that would have made things wildly easier

Despite these hiccups pairing could have been a lot more of a mess, and in the end I think most people ended up with mostly good pairings. However I’ll definitely be taking a different approach next time, and prioritise uniqueness of pairings over anything else (or use a totally different approach, as I talk about below).

Where do we go from here?

Ultimately the event was a success. There were a few blunders on the weekend from me (my hand pairing was messy at times; I made at least one key rule call wrong; I gave the wrong narrative rewards to one allegiance at one point) but ultimately I don’t think many of the players noticed or cared, and everyone seemed to have a good time. It’s something that I would absolutely love to do again, but I think if I do I’m going to approach it a bit differently. Here are my takeaways for what I would do differently next time:

- Custom Missions because my God the missions in the core rulebook are such trash. This is actually already in the works, I just didn’t think it was ready for the weekend and while I was right I still don’t know if it would have been worse. Some of those core rulebook missions are just so wildly unbalanced and unforgiving and don’t give people a real chance. Another thing is I would have liked special operatives to have custom missions rather than just extra objectives.

- Pair for uniqueness and not for match ups or whatever, and just focus on giving people lots of varied games.

- Or not at all because one of the things that I’ve come away from in this is wanting to run a proper map campaign. It’s a different proposition, and I think 24 players is right on the maximum edge of doing it, but I like the idea of supreme commanders directing armies into specific places, each one with a mission tied to it, and seeing what match ups come out of it.

- Give more list building advice would be helpful – a lot of people came to this event with a list they’d put together for it with no chance to try it and tinker, and a lot of folks had clearly struggled to identify what a good take all comers list looks like. That’s something I can maybe help with as an Event Organiser, but also as a writer on Goonhammer, so keep an eye out for some articles on List Building.

Conclusions

I hope this little glimpse behind the curtain has been interesting and maybe has encouraged you to try creating your own narrative event. I was considering writing this up as a pack for other people to run afterwards, but I don’t think it worked well enough to do that with – it was fine but it wasn’t anything exceptional. I’m already thinking about how to do the next one, and we’ll see what comes out of that!