This article is part of Goonhammer’s Year of the Ship. You can see the other articles in this series here.

We’ve done the reading, and we’ve started playing, we’ve even found an excellent place to print ships. Now it’s time to get some real learning in by heading out to find some ships.

I’m very lucky to live in London, land of a thousand museums and home to what was once the Admiralty, the heart and head of the British Naval forces, now a particularly nice part of town that’s half theme park for tourists and half museum complex: Greenwich. Part of that is the Royal Museums Greenwich – including the Cutty Sark (a Clipper), the Royal Observatory (and meridian line), the Queen’s House (not that Queen) and, most importantly, The National Maritime Museum. I was pretty content just to visit, then Greg wrote Historicals Road Trip: Big Boat, and I thought man, why did Greg write a road trip to a boat before I did?

The National Maritime Museum

That wasn’t really the impetus for writing this, because I’ve been meaning to for a while. The National Maritime Museum is awesome, and you should go. If you’re not based in the UK but you ever come here, it should be the big London museum you go visit, because it’s absolutely the best one (and it’s free) and, given the state of political discourse in the UK at the moment it might be one of the most important ones too.

The Maritime Museum covers British (and consequently much of the world) maritime history – battle, trade, colonialism, exploration, racing, immigration, just about everything that has come on, fought in or left via a boat. That means there’s so, so many boats in there. Model boats. Bits of boats. BIG bits of boats. Broken boats. Perfectly serviceable boats. Boat simulators. Damn it’s a lot of boats. More than you’d possibly think would actually fit in there. Even the building itself is tied up in maritime history, once the home of the Royal Hospital School for the orphans of the Royal and Merchant Navies.

For wargamers, it’s an incredible resource. The online collections and art alone will work as both a how to paint and a guide to what you could be collecting. The military history covered in the museum shows the where, when and how of multiple conflicts that could hit your table, but with the human and contextual elements that rule books sometimes lack. I could easily just go through every gallery in this article because it’s all fascinating, made with huge love and enthusiasm for the content it discusses, but for the purposes of year of the ship let’s keep it to the Napoleonic-ish ones.

The big draw for me was the Nelson, Navy, Nation gallery, covering the Napoleonic wars. It’s a great introduction to how the vast fighting fleet was built, recruited, organised and fought, with a focus on the ordinary seamen and the not-so-big man himself. It’s packed with all the stuff I needed to see to get a handle on the lives of the sailors above and beyond Master and Commander, with clear explanation and high display quality making it all impressively accessible. The highlight here has to be Nelson’s coat – the actual coat he was shot in – and the surrounding material on Trafalgar and the subsequent hagiography of Nelson (and scurrilously terrible treatment of Lady Hamilton and her daughter).

Pretty entranced by that on my first visit – with the obligatory long meditation on the life of L’Empereur as his portrait closes out the gallery – I wandered through Tudors (the best introduction to the early days of the slave trade I’ve ever seen), the Arctic (Franklin expedition! Apsley Cherry-Garrard!) and into Pacific Encounters. This gallery traces the interactions between two accomplished maritime peoples – the British and the Te-Moananui-a-Kiwa (peoples of the Pacific), especially once the Napoleonic wars were over and Britian’s warships were turned (in part) to scientific enquiry. There’s a potential there to be all about the destruction of cultures, or, far worse, completely ignore the effects of colonialism on the pacific. Instead, sympathetic and kind curation supports the unravelling of a fascinating story of colonialism, resistance, creation, scientific enquiry and mythmaking, showcasing Pacific voices as active and creative rather than the hapless victims of Cook et al. Intelligent, interesting and considerate – a story the curators were clearly driven by and fascinated in.

The Ships Are Woke Now

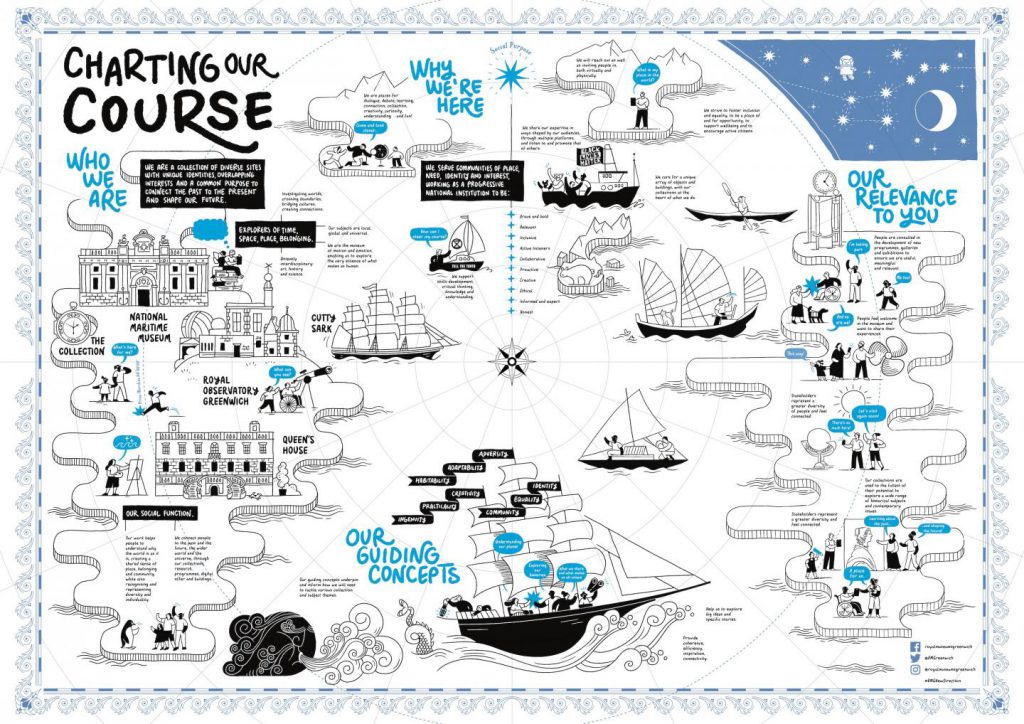

That kindness, consideration and enthusiasm shines through everything there. Sometimes I have a little bit of worry about heading out to what I think will be a military-focused museum. It’s a lot of fun to see cool planes, captured eagles, loricas both squamata and segmentata, but there’s occasionally a drive to focus in too much on the shooty-shooty (or speary-speary), to leave both the reasons for conflict and the impact it has out of it. European naval power allowed for atrocities that have echoed throughout history for centuries. It was created from them, with early transatlantic slavery providing both impetus and capital for mass naval expansion (and innovation), the bones of Britain’s mighty fleets built on colonial exploitation and the lives of god knows how many millions of Africans. So when I turned up for the first time I was a little worried that we’d have a lot of cannon and not much else. But I shouldn’t have been, because greeting you there at the entrance is the mission statement and plan of the museum, nicely illustrated to boot:

Moving around the museum for the first time (baby strapped to my front) was wonderous. Here was a museum that gave you all the flash and excitement of Master and Commander, the sense of discovery and new horizons opening up in front of you as your expedition left port, and the fire and thunder of battle. But at the same time it tells you, backed up by cold hard fact, who profited. Where the money went. What innovations allowed for slaves to be packed tighter and tighter, and how the East India Company turned a continent into a marketplace and wrung it for all it was worth, how the mercantile and scientific exploration of the pacific attempted to end cultures slowly and deliberately. Because those are the facts. Britain didn’t create the slave trade but it was a terribly early adopter. The wealth of the country came from blood and death, for all that the British navy would later become an important part of ending the transatlantic slave trade. These are incontrovertible facts, and they are presented as such, but far more persuasively than you see in many other places.

This seems to be the modern course for National Maritime Museums – visiting the Dutch equivalent in Amsterdam (and again expecting a bit of evasion around slavery and colonialism) I was amazed to find the same tone, the questioning and querying and open discussion, all backed up by the full unvarnished facts of colonialism. Across Europe and beyond there is blood on our hands that no amount of seawater tossed up in a heaving sea can wash off. It’s not about guilt though – but about a determination to face history in all it’s terror, and tell that story. They do it with pride, not pride in the history, but pride in their responsibility, ability and courage to face it. We need this brave and honest reckoning, particularly in the UK, particularly now.

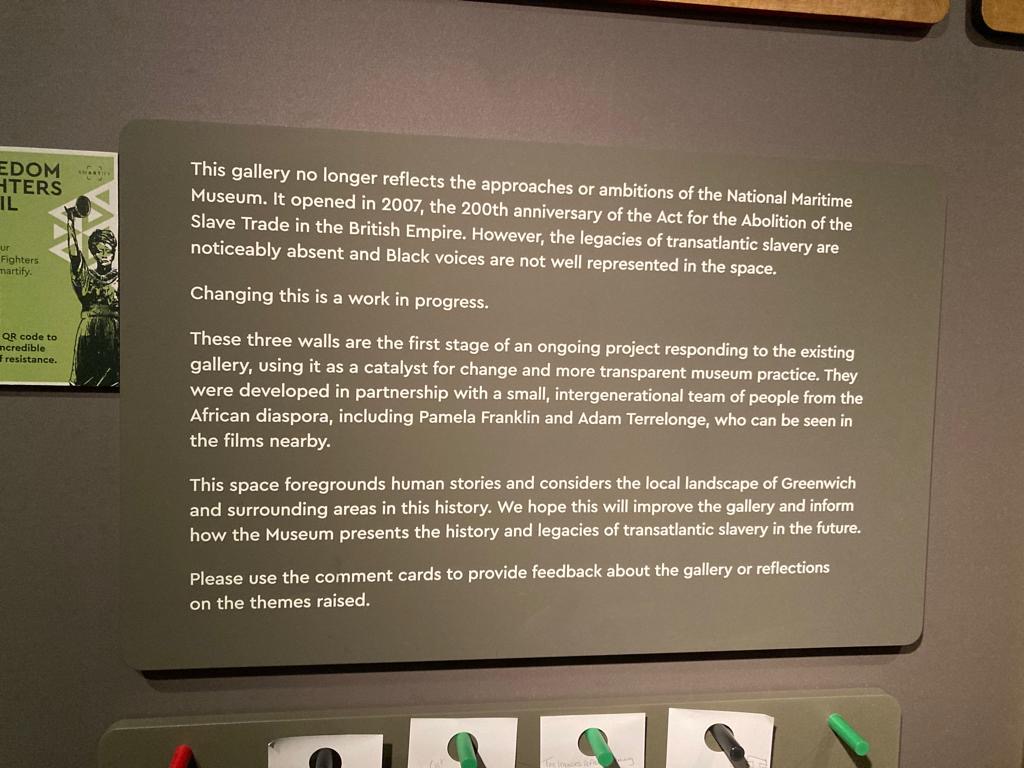

What impressed me most when I think about it was that the museum doesn’t consider this enough. Their transatlantic gallery (which, correctly, discusses slavery as a key part of Britain’s desire to control trade) was, I thought, pretty good – but they disagree. Clear and prominent labelling states that the gallery doesn’t stand to the values the museum holds. Imagine that – no lying, dissembling or avoiding the subject. “It’s not good enough. We will do better.” Inspirational.

Reporting for Parental Duties

So the content is great, the politics spot on, the Nelson coat is there, what else makes the National Maritime Museum worthy of one of our rare Historicals article slots? That it’s perhaps the most kid-and-parent friendly museum I’ve ever been to, that’s what.

I don’t think I could make a conclusive list of what’s there, because every time I go I find something new that just works for me and the kid. Two whole galleries of interactive hands-on content for kids. Frequent parent and child sessions. A massive open play space right next to a café and an adventure playground next to another café. A whole programme just for LGBTQ families to go and network, learn about ships and have a good time. Very good changing tables in male, female and gender neutral toilets that aren’t next to hand dryers. If you have kids, bring them here.

That last one is a good example of the thought that’s gone into the redesign of the museum facilities. I spend a lot of time at museums with my son. Some of that time – too much of that time – is spent asking museum staff to accompany me into the women’s toilets so that I can change my son because there are no other suitable spaces to change a baby, not even the damn floor, getting in the way of disabled visitors who need to use the bathrooms (why does everyone put the baby change there? Those toilets should be accessible and pleasant when needed, not filled with bins of dirty nappies) or putting his ear defenders on because the baby change is crammed into the men’s toilets right next to the bloody hand dryer. Someone, at some point, thought “We should put a usable, comfortable baby change in the male toilets so that men can change their children,” and that person is a hero because many people don’t bother.

I love a museum that thinks and interrogates the history it talks about, rather than just celebrating it and ignoring the bad stuff. I love a museum that clearly cares about visitors as much as it cares about the people it talks about. I love a museum about ships. I love a museum that affords the basic decency of allowing me to change my child. All together, I’ll be heading down to the National Maritime Museum many, many times until I know it all by heart – you’ll be able to spot me there, I’ll be the guy thanking the museum staff for that baby change.

Questions, comments, suggestions? Plans for a trip? Contact@goonhammer.com or leave a comment below