Last time in Part One of our deep dive into wargaming the Ninth Legion, we looked at who, what, where and when – now it’s time to look at the Legion’s possibly untimely end and how you can resurrect them on the table.

What could have happened to the IXth? Was their ultimate fate so mundane that it wasn’t even worth recording, or so shameful that it was never spoken of again?

Before we get too much deeper into rampant speculation, it’s probably best to figure out a set of plausible locations, times and enemies that could have seen the IXth legion’s end. In my mind there are three main possibilities worth discussing, as well as an intriguing, but unlikely, fourth.

Lost in Britain

The first hypothesis is the one that has gained the most traction in popular culture, in which the legion is destroyed during an uprising in northern Britain. Renowned 19th century German scholar Theodor Mommsen first suggested the idea in his multi-volume The History of Rome, speculating that the IXth legion had been destroyed in an attack on its legionary fortress at York by an uprising of the Brigantes tribe around AD 117/118, and that the legion’s destruction prompted the visit of Emperor Hadrian to Britain in AD 122 and the construction of Hadrian’s Wall.

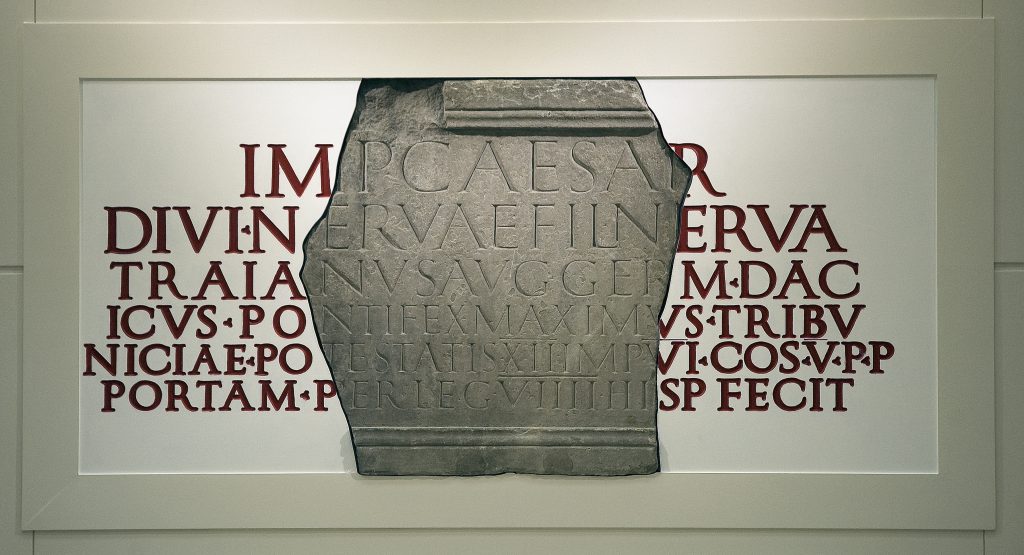

There is evidence to support this idea, hence its initial popularity, but there are a number of problems with it too. The first bit of evidence is an inscription in a stone tablet discovered in York in 1854, and now housed in the Yorkshire Museum, that marks the completion of a gate into the city built by the IXth legion. The mention of the current emperor and his achievements on the inscription allow it to be dated quite easily to AD 108. This is the last dated evidence anywhere in the Empire that mentions the IXth legion, so it would make sense for this to be the site of the legion’s demise.

We also know that by around AD 119, the IXth legion was no longer active in York, as at that time the fortress became the new home for the recently arrived legio VI Victrix. In addition, inscriptions have been found from units involved in the construction of Hadrian’s Wall, units from every legion present in Britain at the time, including the newly arrived VIth legion, but not the IXth legion. It would make sense to assume that the IXth legion was either destroyed or disbanded by this point, or reassigned elsewhere in the Empire.

While there’s no direct mention of a conflict in Britain in contemporary histories of this period that could explain the IXth legion’s end, there are a few off-hand references to some kind of disaster in the province. The Historia Augusta (a series of biographies of Roman emperors of questionable authorship and reliability) mentions widespread trouble across the Empire at the beginning of Hadrian’s reign, specifically saying that, “the Britons couldn’t be kept under control.” A letter from Roman historian Marcus Cornelius Fronto to Emperor Marcus Aurelius also talks about Roman losses during the reign of Hadrian, saying, “what a number of soldiers were killed by the Jews, what a number by the Britons.” Since the Bar Kokhba revolt that Fronto is presumably referring to saw perhaps a legion’s worth of soldiers killed, it can be assumed that the Romans might have suffered losses of a similar scale against the Britons. Combine this with the issuing of coins featuring the image of the warlike figure of Brittania from AD 119, possibly commemorating a major Roman victory, and it seems likely that there was some kind of large-scale conflict in the province, one that could have been bloody enough to bring down an entire legion.

However, Mommsen’s theory does have one major problem: there is no archaeological evidence to suggest that the legionary fortress at York was ever destroyed, making an attack against the IXth legion’s stronghold extremely unlikely. The other popular theory sees the IXth legion destroyed while campaigning far in the north in modern day Scotland (as in Rosemary Sutcliff’s famous 1954 novel The Eagle of the Ninth), but even there we have a number of issues as well. Simply put, there’s very little precedent in Britain of the kind of large-scale battles that could be capable of wiping out a legion. Both of the large-scale Roman invasions of Scotland, by Agricola around AD 80 and by Septimius Severus around AD 210, saw very little in the way of pitched battles, and given the fractured nature of the native tribes at that time it’s difficult to imagine any kind of conflict occurring in Britain that could have wiped out a whole legion.

A Great Fire in London

So, if we rule out the north of Britain for now, could the IXth legion have been lost in the south of the province? After all, the event in Britain that came closest to wiping out a legion was Boudicca’s revolt, and that didn’t originate from Scotland but from the Iceni around Norfolk. Here there’s an intriguing, if admittedly unlikely, possibility. What if the IXth legion met their end in the heart of the province, in a war that never made it into the history books?

In 2017, Dr. Dominic Perring of University College London published an article that added another dimension to the conflicts in Britain in the early 2nd century. By looking at three main pieces of evidence, he proposed the existence of a hypothetical ‘Hadrianic War’ that would have taken place in the provincial capital of London in the AD 120s. After its destruction by fire during Boudicca’s revolt, the city of London isn’t mentioned in any written history until it is sacked in AD 296, but that obviously doesn’t mean that nothing happened in London in the years between. Excavations in the 1940s found widespread evidence of another major fire in London commonly dated to around AD 125 based on the discovery of certain pottery and coins, and while traditionally the fire has been assumed to be an accident (as was the case with the famous Great Fire of 1666), Dr. Perring argued that arson was the cause by comparing the damage to the similar destruction that took place during Boudicca’s revolt.

Another piece of evidence he mentions is the discovery of the unfortunately-named Cripplegate fort, built almost immediately after the fire, and measuring a little over 200 metres on each side. Urban garrisons were rare, though not completely unknown, in the Roman Empire, and the fort itself was arguably larger than necessary to house the expected number of troops that would be based in London. Such a fort being built so soon after a major fire would suggest that it was placed to supervise the reconstruction in an environment where there was a serious possibility of a military threat.

Finally, there are the hundreds of skulls that have been discovered in the vicinity of the subterranean Walbrook river. The first of the skulls were uncovered all the way back in 1838, during sewer construction, but they may have been known about for even longer, possibly providing the inspiration for a story from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain about a massacre of Roman soldiers, written in the 12th century AD. Large numbers of bodiless skulls have continued to be discovered since, with most dating to the early AD 120s. The skulls mostly belonged to young men, and many featured signs of battle. While the skulls could have been separated from their bodies after burial due to storm-surges, it seems more likely that they were trophy heads taken after a conflict, perhaps by attacking Britons. By this point in the Empire’s history, however, headhunting practices had begun to work their way into the Roman military, particularly among auxiliary cavalry units of Germanic and Gallic origins. This raises another possibility, that the skulls were taken during a rebellion in London, either by rebelling auxiliary troops, or as a punitive action by auxiliary cavalry against a rebelling populace.

There’s also one last decapitation to discuss, this time a bronze head of the emperor Hadrian recovered from the bottom of the Thames, roughly hacked from the rest of the statue in an act of iconoclasm. This further suggests some kind of rebellion in London (or at least a rebellious mood) following the statue’s likely commission in 117 AD to celebrate Hadrian becoming emperor. Such a rebellion could have done significant damage to the IXth legion if it was present, or even destroyed it altogether, and there’s even the slim possibility given its mutinous past that the IXth legion were the ones leading the rebellion.

By way of balance, it’s also worth mentioning that there is essentially no evidence of conflict during this period anywhere else in southern Britain, meaning that unlike Boudicca’s revolt any conflict was likely confined to the capital alone. Dr. Perring also makes no real mention of the IXth legion in his article, but the timing of the fire around AD 125 does put it awfully close to the time of the IXth legion’s disappearance, offering a tantalising connection. Simon Elliott expands on this connection in his book Roman Britain’s Missing Legion: What Really Happened to IX Hispana, which served as a basis for a lot of my research for this article.

While the IXth legion’s fortress of York was around 300 km from London, the direct route between them along Ermine Street meant the IXth legion would have been able to reach London quicker than either of the other legions at Caerleon and Chester, making them the most likely legion to have been involved in any conflict there. All in all, this provides another interesting option for the legion’s disappearance even if it’s not quite as likely as it being lost in the more conflict-heavy north of the province.

Elsewhere in the Empire

If we go beyond Britain, there are some further possibilities, but again there’s nothing conclusive. Notably, during the mid 2nd century, there were multiple conflicts in the Middle East that resulted in significant Roman losses. The first of these is the Third Jewish Revolt (also known as the ‘bar Kokhba’ revolt after its messianic leader) from AD 132 to AD 135, which saw six full legions redeployed to the area along with auxiliaries and detachments from a further six legions. The early revolt was incredibly successful, but they were eventually defeated, though not before dealing out heavy losses to the Romans leading to at least one legion being disbanded afterwards by Hadrian. This could have been the IXth legion, but more likely it was Legio XXII Deiotariana, which had been stationed much closer to the area than the IXth legion, with the last record of it dating to AD 119.

The Parthian War from AD 161 to 166 is another possible candidate for a conflict that could have wiped out the IXth, and Cassius Dio describes a Roman legion being hemmed in and shot down by Parthian forces in Armenia. This could have been the IXth, or again it could have been XXII Deiotariana.

The biggest issue with using either war to explain the IXth legion’s disappearance, however, is that there’s simply no evidence to suggest the IXth legion were ever anywhere near the site of either conflict, and both occurred long enough after the IXth legion would have left Britain that they should have left some archaeological evidence of their presence in the area. Transferring an entire legion from one end of the Empire to the other would also have been an incredibly expensive undertaking, and unlikely to be worthwhile compared to moving a closer legion.

If the IXth legion were moved to the Middle East at any point, the most likely time would be during Trajan’s war against the Parthians and the Second Jewish Revolt around AD 114-117, where the chaos of those conflicts could have seen the legion repositioned there around the time of Trajan’s death. Removing one of Britain’s three legions from the province would likely have left it vulnerable, making it easier for a rebellion in the province or an invasion from the north to gain hold, potentially causing the conflict in Britain at the beginning of Hadrian’s reign.

Before I talk about the wargaming potential of the IXth legion, however, there’s one more piece of archaeological evidence worth discussing. In 1959, an excavation of a Roman legionary fortress in Nijmegen in the Netherlands uncovered a fragment of a Roman roof tile bearing the stamp of the IXth legion. The Romans commonly stamped their ceramic building materials to identify the brickyards where they were produced, and if they were made by one of the specialist tilers serving among the legionaries they would be stamped with the legion’s mark. Over a hundred more roof tiles with the same mark were identified at the site, found alongside coins allowing them to be dated towards the end of Trajan’s reign and the beginning of Hadrian’s, making it seem likely that the IXth legion was present there at some point in the early 2nd century. We also know that Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix took over the fortress around AD 120, before it was abandoned five years later.

This would put the IXth legion in Germania between around AD 104 to 120, except for one tiny problem with the roof tiles. You see, Roman numerals weren’t always written in a consistent format across the Empire. The number nine would normally be written as IX, but could sometimes be written as VIIII. The problem here is that the Nijmegen tiles are stamped ‘VIIII’, while the bricks found at the legion’s home of York are stamped ‘IX’. Looking elsewhere for other tiles with the Nijmegen-style stamp, the only place in Britain that uses the ‘VIIII’ stamp is a Roman brickworks in Cumbria, along with the fortresses nearby. This paints a pretty clear picture that the IXth legion presence in Nijmegen belonged to a single detachment, rather than the whole legion.

Even if the whole legion had been stationed in Nijmegen, however, there wasn’t really a viable conflict that the legion could have been destroyed in during the period it would have been stationed there. The closest option would be the Marcomannic Wars beginning in the mid-AD 160s, the aftermath of which led to half the legions in the Empire being stationed along the Danube and the Rhine in preparation for future conflict. However, as with the conflicts in Parthia and Judea, there’s no evidence that the IXth were present in the area anywhere near the beginning of the war, making it unlikely they could have been involved.

Looking at our options overall, the most likely options seem to be that the IXth legion was lost in Britain as commonly accepted, or potentially that they were lost during the tumultuous conflicts in the Middle East following Trajan’s reign.

Wargaming the Ninth Legion

The IXth legion sits at an interesting intersection of history and mythology, certainty and mystery. We know a lot about their history, even down to the names of certain soldiers, but we will likely never know their ultimate fate. That combination gives them a vast amount of potential as a wargaming force. You can use them to refight existing known battles, such as at Colchester against Boudicca and the Iceni, but they also have justification for use against German, Parthian, or other forces in a “what if?” style scenario.

The legion also serves as a great backdrop if you want to mix fantasy elements into your historical wargaming. There are all kinds of fantastical explanations you could use to explain the IXth legion’s disappearance, from the legion being transported to another world as in Jim Butcher’s Codex Alera series, to it being wiped out by otherworldly monsters like in the Doctor Who episode The Eaters of Light. Once you add some supernatural elements into the mix, the possibilities are endless.

As a lost legion, they’re also uniquely suited to one of my favourite wargaming scenarios, the doomed last stand against innumerable foes. It can be a lot of fun to test your skills as a commander by seeing just how long you can survive in a no-win scenario against an enemy whose units reappear every time they are defeated.

For wargaming the IXth legion and their foes, there are a number of options. The first to recommend would probably be Hail Caesar from Warlord Games. It’s primarily designed for large-scale battles from any point in ancient history, and while this may be good for representing general warfare in the Roman Empire, it’s not so well suited for the kind of conflict that the IXth legion would have been involved with in Britain. The northern Britons did their best to avoid set-piece battles in general, with the only major battle of Agricola’s campaign in the far north taking place at Mons Graupius in AD 83, and though the IXth legion were present for the battle only the auxiliaries were involved in the actual fighting. Similarly, Septimius Severus’ third century AD campaigns in that area didn’t see a single set piece battle take place despite him deploying a huge force of 50,000 men.

Conflict in Britain actually tended towards either siege warfare against native hill forts, or guerrilla warfare against the Roman occupiers. For the latter type of conflict, Infamy, Infamy by Too Fat Lardies is your best bet as it’s been specifically designed to represent that kind of asymmetric warfare with native ambushes against well-drilled Roman soldiers. You can play as Republican or Early Imperial Romans against Britons, Gauls or Germans, with the barbarian forces getting to deploy from terrain through the use of ambush markers. The Romans rely on formations and maneuvers to achieve victory alongside their auxiliaries, while the barbarians fight in mobs and try to build up fervour to gain considerable bonuses. This makes the game an excellent choice to play out the IXth legion’s last battles whether you think they happened in Britain or Germany, though there’s no rules for Middle Eastern conflicts so there’s no real option to simulate that aspect of the IXth legion’s potential history.

If you want to bring supernatural elements into the story of the IXth legion’s disappearance, then Broken Legions from Osprey Publishing is probably the game you’re looking for. It’s a skirmish game in which warbands of roughly 5 to 15 models a side fight over treasures and relics at the edges of the Empire. There are a number of factions ranging from the Roman legions and slave rebellions to barbaric tribes and ancient cults. Most factions have some sort of supernatural unit option, such as werewolves for the Barbarians or Lamassu for the Parthians, but they can all take models from the auxiliary list at an extra cost, including centaurs and demigods. There’s a small number of options for wandering monsters and a very basic campaign system, but it’s a solid system if you want to play a battle between soldiers of the IXth legion and supernatural monsters assisting the enemies of Rome.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it is unlikely that we will ever know the true fate of the IXth legion, barring the appearance of some truly extraordinary new evidence. That doesn’t mean it’s not worth thinking about, though, and by taking the time to examine how the IXth legion could have been lost, we can learn a lot more about the Roman legions and the Empire as a whole.

Personally, I imagine the IXth legion was lost in Britain around AD 120-130, victim not of one single disaster, but of a series of crises across the province, perhaps involving a war in the north or a rebellion in London. Mix in a possible mutiny, and you’d get a series of events that could cause enough losses and shame to force an already struggling legion to disband, without any single event being notable enough to be worth recording. Maybe a somewhat anticlimactic end to a legion that had survived so much, but not one without its wargaming possibilities.

As historical wargamers, we’re always finding things we can’t be certain about, from the precise shade used on the uniforms of a certain period to the location of a battle or the exact numbers of soldiers and losses involved. Often we can spend a long time trying to ascertain the exact truth of the past, but to me the story of the IXth legion is a reminder that we won’t ever know everything about that past, and that historical wargaming doesn’t have to be just about known battles between known armies with known outcomes. It can also be a way of engaging with the mysteries of the past and reveling in the ambiguities of history.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.