No, it’s not the Maori wars; that’s actually surprisingly popular and well-supported.

Or the Emu wars; again, small but surprisingly well-supported.

Or even the Boer War (bigger, but quite poorly-supported – you’re getting closer though).

No, it’s the big one, the great granddaddy of the 20th century, a war so fusty in the popular imagination that it has favorite comfy slippers and ties an onion to its belt.* World War One. Or the Great War as it was known by its contemporaries, because well… they were very optimistic it would be ‘the big one,’ the war to end all wars. We all know how that worked out.

Wait, I hear you call plaintively from your muddy shell-hole, shouting over the sound of the relentless guns, “People do game the First World War! I saw a demo game of it one year at Salute.” I mean, I’m sure you did; so did I, and I bet those same guys come back every year, but think how many more people you’ve seen gaming basically every other conflict from the 20th century, or the preceding century. How many times have you actually seen the Great War played at your local club, for example?

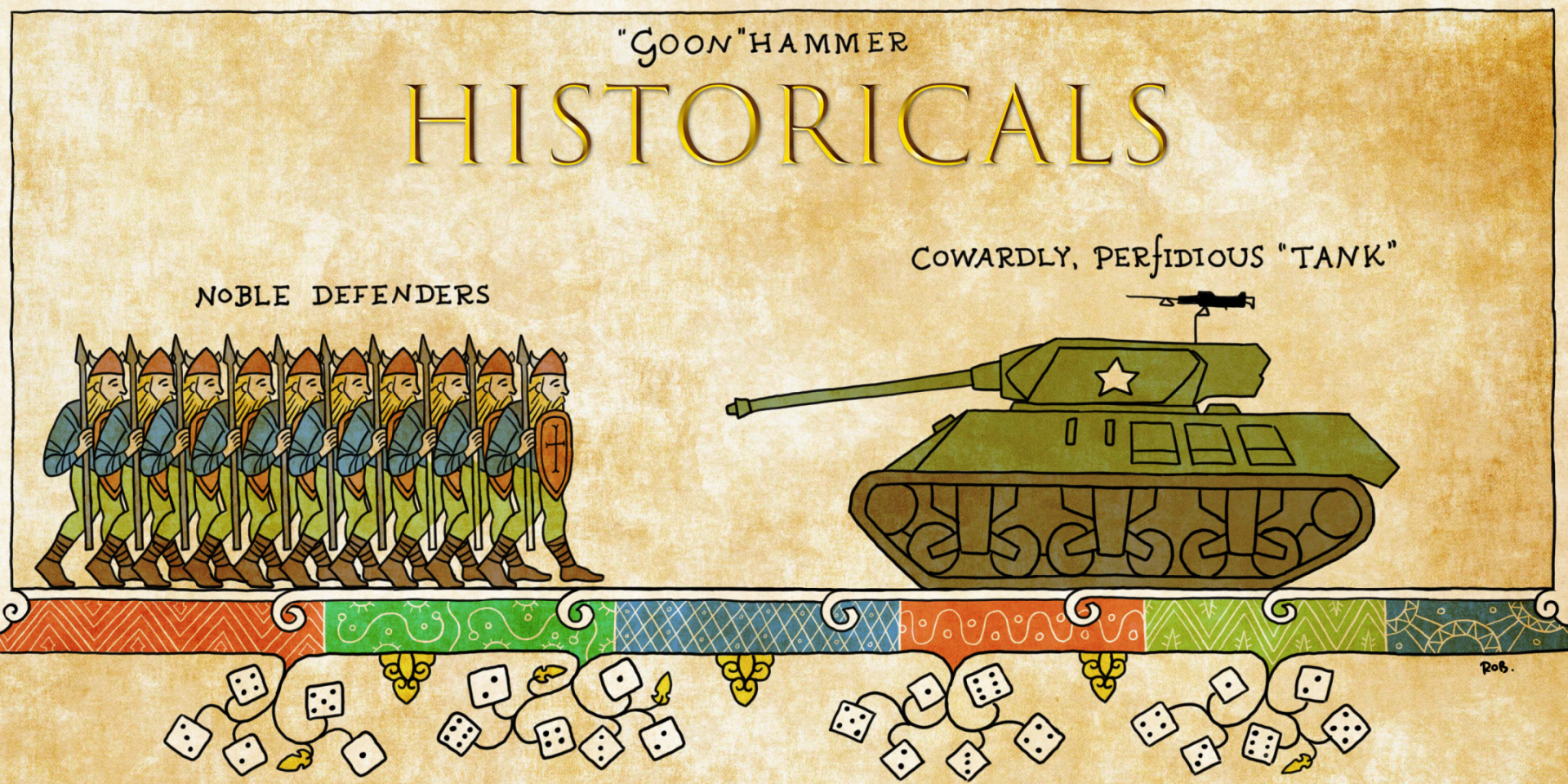

Now, we all know that some periods are wargaming darlings (that’s Captain Darling to you, baaaaah!), and get a disproportionate amount of attention: WW2, the Napoleonic wars, and the wars of Rome jump to mind. Basically, anything involving a ruthless tyrant armed with eagle symbology, a flawed understanding of history, and an inflated sense of self-worth (see also the Emperor, 40k). By these rules the Great War should qualify, not least because the rulers of half the combatants were literally called a transliterated form of Caesar.

Perhaps confusingly, amongst historical gamers there are some niche wars which are surprisingly popular. This is generally because a) they involve a British or American person in some capacity, or at least someone white; b) have a great movie depicting them (see a, the usual pre-requisite); or c) happen to have a really extensive and well-sculpted range of miniatures available for them for trifling reasons, despite no-one having heard of the conflict prior to this (Carlist wars, I’m looking right at you).

What then of the Great War? Why does it languish in such a lacuna of disinterest and neglect? There is a strong argument that without it, the 20th century would look very different: no Russian revolution, no Versailles treaty, no Nazis, no WW2, no imminent collapse of Empire, and so on. Put simply, the repercussions of the Great War strut across the stage of world history like a procession of titanic butterflies, flapping their fucking massive causal wings.

But perhaps this disconnect shouldn’t come as a surprise; after all, we don’t wargame things just because they were highly historically significant, do we? If so, we should probably be wargaming agrarian reform (farming28 anyone?). No, we wargame a historical period for a whole host of reasons, reasons that I am going to show you are written all over World War One like cartoon dicks on a sleeping stag’s face. Let’s get all Adam Savage on this and bust some myths.

Myth #1 – It’s boring. It’s just endless trench warfare in a muddy field in Belgium.

So, yes, there was lots of fighting in a muddy field in Belgium.

But this a) misses just how interesting fighting in a muddy field can be, b) misconstrues this as the character of the whole war, and c) assumes that the western front was the only front of consequence or interest.

Let’s unpack.

We need to get something out of the way before we go any further; yes, lots of young soldiers did tragically attack trench systems in line abreast and get mowed down by machine guns and modern artillery. For a time. A TIME. In an arguably similar manner to which Allied commanders early in WW2 struggled to adapt to ‘blitzkrieg’ maneuver warfare (and in the case of the Western Desert campaign, literally drove backwards and forwards across North Africa until they worked out how to do war), generals in the Great War grappled with the new challenges posed by positional warfare in the industrial age.

However, adapt and overcome was the name of the game. 1914 and 1915 demonstrated the limitations of existing weapons and doctrine. 1916 and 1917 saw considerable innovation and experimentation – tanks, aircraft, trench mortars, flamethrowers, small unit tactics, creeping barrages and many other new technologies and techniques were developed. By 1918, Allied forces had configured the different arms of modern warfare – infantry, armour, artillery and aircraft – into a battle winning machine. They broke the German army tactically, operationally and strategically. They unwound trench warfare and drove (literally) into the green fields beyond the lines.

Let me pose a question to you: Picture a graph. What is more interesting — the fuzzy foothills and noise after a period of major change, or the peak of change itself? So it is, arguably, with the Great War and what came after in the 30s and 40s. The Great War literally tore up the 19th century rulebook of warfare overnight and forced it to be rewritten over four bloody years. By wargaming WW1 you get to be an early adopter, and figure shit out. Necessity may be the mother of invention — but sometimes she can be a right pain in the arse.

And lastly on this point: While Belgium and the rest of the western front was a hugely significant theatre of the war, there is much to interest and excite elsewhere. From the dashing cavalry charges and zooming armored cars of Palestine, to the freezing peaks of the Alps and Macedonia. From the sweeping expanse of the eastern front, to the claustrophobic landing beaches of Gallipoli. Each theater brings its own challenges and opportunities. Revolutions, civil wars, and mutinies. What’s not to like? If it seems boring, it’s because you’ve not had occasion to look hard enough. I haven’t even started on the Czech Legion. Seriously, Google that shit. You couldn’t make it up.

Myth #2 – I need trenches. LOTS of trenches. (And shell-holes, and other terrain I don’t have.)

It does help to have these terrain pieces in your collection, after all, one of the unique and interesting facets of wargaming the Great War is that you can explore the ‘defense in depth’ tactics that were used and spice up your tables with these fortifications. However, you really don’t actually need to. For example, by 1917, the main battle zone of the German defensive system was not in fact the trenches. Rather, the few miles of country which lay behind the trench lines was. This ground, unseen by Allied artillery observers, was enfiladed by machine gun nests and swept by artillery fire. The German operational mantra was to counter-attack quickly and violently, so something which looks essentially like a meeting engagement is not at all off the cards. Also, by the end of 1918, the Allies had more or less broken through in several places – see Myth #1.

So in many cases, you can actually use the same sort of terrain you’d use for your WW2 games, so long as you set your games early or late in the war, or on the eastern front. However, if you really want to do Verdun or the Somme or Paschendale, then yes, you are gonna need to reach for those trenches and shell-holes!

It’s worth saying that there are good, affordable options for trenches. You don’t have to have a fully landscaped foam setup at all. You can get decent and affordable trenches in MDF from Sarissa and in vacuum formed plastic from Amera. 3D print options are also available. They will need some finishing with earth effects and paint, and perhaps some corrugated card and barbecue skewers, but it’s a fun and accessible project ultimately. Trenches were, frankly, quite shitty things, and often period photographs (rather than diagrams of the ideal trench) show they were quite informal and, particularly at the beginning and end of the war, not at all that elaborate. They can also be recycled for WW2, where trenches were still widely used. Or really any conflict in the 20th, 21st, or latter half of the 19th century!

Myth #3 – Everything is brown.

Mud is brown (more or less), there’s no getting away from that. However, the painting opportunities of the period are actually quite interesting.

In its opening stages, the war is a riot of colour. The French cavalry is quite literally wearing uniforms from the Napoleonic wars, complete with cuirasses and plumes, and the infantry are in red trousers (and absolutely obsessed with the things – one French general famously proclaimed “France is red trousers!”). Later in the war, after an identity crisis and the most confusing procurement journey you’ve ever seen, the French are rocking horizon bleu (pale grey-blue). No-one, even they, really knows why, but it does look very dapper and is fun to paint.

Early on, the Germans have the famous spikey pickelhauber (if you’ve ever seen a plague marine, you’ve seen a pickelhauber) and later the classic stahlhelm most people know from WW2. They also wear the classic 50 shades of feld grau (field grey), with variations in trim and etcetera, so you can argue over that for hours if you want (or don’t).

Russians and Italians are in various shades of green, and the former get some really cool uniforms for cossack units and the all-female ‘death battalions’ (sorry ladies). Meanwhile, Austro-Hungary, an utterly bonkers polyglot empire of different central European ethnicities, has all the uniforms, all of the time. The Ottoman and British Empires are mostly in various shades of khaki, and yes there are pith helmets (!).

Did I mention trench armour and trench weapons yet? Brutal looking knives with knuckle-duster handles and clubs with nails in? Segmented steel armour that looks like it has been looted from a castle (and in some cases, was)? If you’ve been wondering where some Warhammer 40k factions get their design aesthetic from, look no further. Aesthetically, WW1 brings a heady fusion of late-Victorian diesel punk, brutalist medievalism and early 20th century cubism. What’s not to like?

Camouflage was in its infancy, which means you get lots of weird and wonderful variations of dazzle camouflage schemes on tanks, guns, ships and even, in the case of German stormtroopers, helmets. By 1918, the Allied forces were making extensive use of tanks of all shapes and sizes, were developing gun and armoured personnel carriers, and cavalry even made a come-back as the frontlines broke-up. Indeed, on the eastern front and Palestine, cavalry never left and were extensively used throughout the war, often to great success. So if you like painting horses, go nuts.

Don’t even get me started on the planes. So. Many. Pretty. Colours. Zooooom.

Myth #4 – It’s a meaningless war a very long time ago, about people and things I don’t care about, and can’t relate to.

Au contraire. Remember that bit where I said that WW2 just wouldn’t have happened without it? Or Nazis? There are historians who make a pretty plausible argument that WW1 and WW2 should be seen as one war, with an intermission.

That aside, if you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you live in a Western, anglophone country. As such, you probably quite like the fact that you can vote, practice your religion (or none) and hold opinions, at least in the privacy of your own head. All of these are predicated on living in a (relatively) functional democracy. While it’s simplistic to view WW1 as a war of democratic nations vs. autocratic ones (the Tsars weren’t noted for their love of the Duma), there is a kernel of truth in that. France, Britain and the USA had 99 problems – but naked autocracy wasn’t one.

Of course, what we can’t forget is that they were all imperial bastards (yes, even you America, I saw what happened in the Spanish-American war and the Philippines). Indeed, in large part Germany was so up for a fight exactly because it saw itself as the poor relation left out of the groaning colonial buffet.

The better reason to be interested in the Great War is the people. Normal people.

There is something fascinating about the juxtaposition of the relatable and unintelligible in WW1. On the one hand, Ernst Junger**, in his seminal memoir of WW1, Storm of Steel, will relate how terrible a thing the experience of war, death and destruction is; how wonderful a cup of hot coffee is when served in a soggy trench at 3 a.m.; his esteem for the Englishmen who help him to the rear when wounded, and yet at the same time; his joy at the excitement of combat, his thrill in violence, and the war’s value, in his eyes, as the ultimate expression of manliness and one nation’s superiority over another. To some degree, he actually enjoys the war, or at the very least, sees it as worthwhile. It is a mindset that, fortunately, many of us these days find hard to relate to, at least in the same way. King. Country. Duty. Honour. These aren’t dead concepts, but they have changed radically in the popular imagination and have gained considerably more nuance and qualification. WW1 is a fascinating viewpoint on the peoples of Europe at the turn of the century.

If nothing else, WW1 is about the extremes of the human experience. If you want to know what it looks like to push the average human being under arms to the absolute edge, to see in short, their best and their worst qualities in the face of unbelievable hardships, then WW1 is that.

Also, there are some actually good movies now, so it just became a lot more accessible.*** There have long been good books and memoirs, so don’t forget to dig into those well. I’ve already mentioned The Storm of Steel, but interesting characters (read: bastards) from WW2 rear their heads, such as Erwin Rommel, in his WW1 memoir, Infantry Tactics, and you know, that piece of shit who caused a lot of trouble later on in Weimar Germany. A really good starting point is the Great War Youtube Channel which has great specials on interesting battles, uniforms and weapons, personalities, the evolution of tactics and strategy, and so on, as well as week by week commentary on the entire war (if you just can’t get enough WW1 content). You will most definitely learn something, and be entertained. I would also recommend Dan Carlin’s podcast Hardcore History, which has a 6 part series on WW1, Blueprint for Armageddon, and Alex Sotheran’s Youtube channel, Storm of Steel for thoughts and battle reports on wargaming WW1****.

[Lenoon edit: With my fondness for French armies, Socialism, and Pacifism, I’m going to interrupt Eccentricbear to recommend Poilu: The First World War Diaries of Louis Barthas, Barrelmaker. The French infantry experience from the sharp end by one of the great soldier-diarists, a committed socialist, fantastically sarcastic bastard and anti-war activist. Noone will ever regret reading Poilu]

Anyway, that’s enough from me on WW1 for now. If you take one thing away from this article, watch All Quiet on the Western Front, and then tell me you don’t want to re-stage the battle sequence with all the tanks and flamethrowers.

Rattle. Boom. Pwhoosh.

*As was the fashion at the time.

**The OG mad lad of WW1

***Hard recommend for 1917 and All Quiet on the Western Front.

****Can you see where he got the name?

Questions, comments, suggestions? Email contact@goonhammer.com or leave a comment below!