When studying early-modern European history, military historians tend to offer two kinds of names for their favourite wars. The first of these are those named after specific events: revolutions, successions, invasions, or the removal of someone’s ear.

The other kind of war name involves the length of the conflict, and these confirm two great truths. The first is that historians, despite having pretty much one job, are rubbish with dates. The Hundred Years War ground on for well over a century, and the Seven Years War lasted at least eight years, maybe nine if you ask a Canadian.

The other great truth is that naming a war after a length of time tends to mean it was a serious affair. The Nine Years War (1688-97) saw most of Europe struggle to defeat France on several fronts. The Seven Years War (1754/5-1763) makes a strong case for being the first true world war. Most impressive of all were the Dutch, who fought for eighty years before securing their independence from Habsburg Spain (1568-1648).

But the great granddaddy of all number-named conflicts is the Thirty Years War. Spanning 1618-1648, it contains battles big and small, a military revolution, incredible characters and some of the easiest paint schemes in the historicals hobby. This is the era of the mercenary, the vagabond and the floppy hat. Moustachio’d musketeers dueled in chateaus as mud-covered blocks of pikemen tramped into cannonfire, dozens of flags flapping in the wind. Leaders led from the front, and often died doing so, meaning you finally have a historical excuse for shoddy generalship and poor dicerolls.

If any of this sounds appealing, the Thirty Years War may just be for you.

I’ll start with some historical context. This will not be all-encompassing, and if I miss your favourite general or atrocity I apologise profusely. I’m also focusing on the war in Germany, since that is the most well known. So to the Dutch or Italian readership, I also apologise.

I’ll then talk hobby, and explain why this may be one of the most accessible yet difficult periods to wargame “accurately”, and why you shouldn’t care.

The Beginning (or, Why You Should Never Hire a Czech Window Cleaner)

When I worked in Games Workshop, there were three forbidden topics: Money, politics, and religion. Unfortunately for Europe, Ferdinand II, soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor, did not get this memo in 1617. Ferdinand was staunchly Catholic, finding Protestants to be confusing and heretical. But, like any early-modern monarch, he was willing to look the other way if it secured him power, and he was crowned King of Bohemia under the express condition that he would respect religious freedom there.

Naturally, Ferdinand began to suppress religious freedom in Bohemia almost immediately, prompting local nobility to storm Hradčany castle and hurl three diplomats out of a window. This event became known as the Second Defenestration of Prague, suggesting that this was a common enough event in the city and setting a precedent for Russia’s preferred Oligarch Removal System.

With the dice (and diplomats) cast, the Bohemian nobility was in open rebellion against the Hapsburgs. In 1619, they crowned their own king, Frederick V, and prepared for the wrath of Ferdinand. Things came to a head only a year later at the Battle of White Mountain where Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, smashed the rebels. And thus, the Two Years War came to an end in 1620, and they all lived happily ever after…

Except that didn’t happen, and the Protestant forces in Germany continued to rebel. On top of this, more and more European powers began to get involved. It’s easy to think of the two sides as Catholic and Protestant but there was plenty of team-swapping in between (which is great for a wargamer, you’re rarely pencilled onto one side).

The most significant foreign power to get involved at this early stage was Denmark, led by their extremely popular King, Christian IV. His army contained many veterans of a prior war with Sweden, and he marched to the aid of the Protestant armies of Germany, confident of success. His confidence proved to be misplaced, as he was unfortunate enough to run into two of the best commanders the Imperial cause had to offer; Tilly, and Albrecht von Wallenstein. Wallenstein was Scrooge-McDuck level rich, and a capable commander to boot. With Tilly’s veteran troops and Wallenstein’s massive war chest, the Danes were quickly driven back to Denmark, playing a secondary role thereafter.

The Middle and End: Swedes, Sabaton and Cardinal Sins

France had been happy to watch the Hapsburgs tear themselves to pieces for a decade or two, but when they heard news of Tilly and Wallenstein’s triumphs over the Danes, they were worried. They needed a new plan to disrupt the Imperial cause. Cardinal Richelieu, de facto leader of France at this point, was a firm believer in putting the state first. And so, he decided to make a deal with the devil. The Catholic cardinal sent envoys to the Swedish King Gustav Adolph (Gustavus Adolphus) and an alliance was struck.

Gustavus Adolphus was a military innovator, worthy of the power metal ballads associated with him. His army carved through Imperial forces, notably at Breitenfeld (1631), and swung momentum back towards the anti-Hapsburg alliance. Unfortunately, he had an old neck wound that meant wearing armour was uncomfortable, which combined with his penchant for leading from the front meant that he was found dead in a ditch when the fog lifted at the battle of Lutzen (1632).

The Swedes had done well, but the death of King Gustav lamed their campaign. France could no longer stand by and just pay people to do their fighting for them. And so, French armies marched to war, led by some of the finest commanders of the century. The dynamic duo of the Prince of Condé (known as the Great Condé) and the Viscount of Turenne spent several years pummelling Spanish and Imperial Forces across Europe. By 1648, pressure was mounting on both sides to secure a peace and, in August, violence halted in Germany and cautious negotiations began. The Thirty Years War was finally over.

Wargaming the Thirty Years War

An army of the Thirty Years War is very recognisable. Bricks of pikemen, flanked by sleeves of musketeers are arrayed in pretty patterns across the battlefield. Large numbers of cavalry, ranging from Finnish light cavalry on tiny ponies to heavily armed Cuirassiers, sweep around the flanks. Artillery, both light and heavy, ply their trade throughout, and dragoons and harquebusiers offer tactically flexible options for a war of manoeuvre. But before you sprint out to start building your forces, there are couple of points worth mentioning.

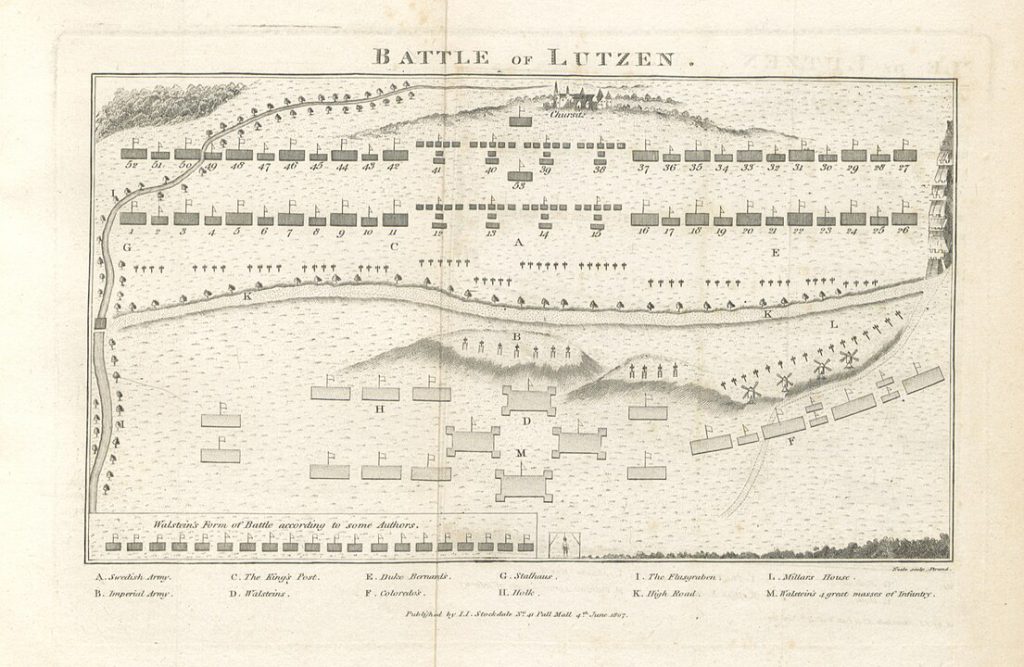

Getting the scale of engagements right for this period is very difficult. Look at the map below.

Notice how deep those ranks are. It was common to go into battle with no fewer than 10 ranks of pikemen. This means that to a purist, your units should be thicc with as many c’s as is currently appropriate. At 28mm scale, some companies package their pike blocks in 16s or even 12s. This looks fine, but if ever there was a period that benefits from large numbers of models in a unit, this is it.

Of course, none of this actually matters! Wargaming is not the creation of a moving diorama, and if you want to have smaller pike blocks for storage, financial or any other reason that is perfectly fine. My 28mm pikemen are only in 4 ranks, and I like how they look on the table. Do what makes you happy, and if some jerk in a comment section complains about it, defenestrate them.

For the painter, uniforms weren’t common, offering considerable freedom when assembling your force. Protestant forces often donned a white sash or green saplings, while Catholic Imperialists regiments preferred a red accent to distinguish them from their enemies. It is completely reasonable to see a regiment in a hodge-podge of muted colours, next to a bright red, green, grey, or blue regiment, newly equipped. For those who like metallics, armoured cavalry allow you to play around with blackened steel, gleaming metals and anything in between. And for those who crave uniformity, the Swedish army had colour-coded regiments which stand out nicely on the battlefield. There is something for everyone here, and happily, there is a model range for every preference too!

Models

6mm

The best option here is Baccus. At this scale, you can represent pike blocks and deep ranks of musketeers without taking out a mortgage for the miniatures. Not only that, but they offer a specific “Big Base” unit which has a healthy pike block and deep sleeves of muskets in a convenient bundle. For those who want to nail “the look”, this is a good place to start.

13.5-15mm

When Warlord Games released an “Epic” range for the mid 17th century, I was very excited. On closer inspection, the cavalry sculpts left a little to be desired. Happily, there is a solution to this problem (if you can order from the UK). Steel Fist Miniatures have an excellent range of metal models which size well next to Warlord’s offerings. Yes, technically they are English Civil War, but anyone who calls you out on that should be tickled with a Swine Feather. By combining these two ranges, you get the value of plastic, the joy of painting 28mm models, and “the look” of the 6mm range.

28mm

If you like plastic models, you have one option: Warlord Games. Within that one option are three venerable sprues doing an awful lot of heavy lifting. Each of the kits that Warlord sells (Imperial, Swedish, assorted English Civil Wars) include the same sprues, and a small selection of metal components to make them look more period/nation appropriate. Warlord’s metals are quite good, given their age, but better options are out there (if for a higher price).

Bloody Miniatures produce wonderful, characterful metal models which are perfect for either a skirmish game or adding some charm to a larger unit. 1898 Miniatures, based in Spain, have some of the nicest Spanish infantry and cavalry available for this period. The models are very well researched, and they are adding French infantry as well! I have a block of these which will become a generic Imperial regiment, so don’t be put off by the national labels. Most models are pretty interchangeable.

It wouldn’t be a historicals article without mentioning the Perry twins, whose English Civil Wars range proxies across to the Thirty Years War very well. Bicorne Miniatures also have a lovely range of English figures which can be used on the continent. The Assault Group have a huge array of metal miniatures for every faction in this conflict, but they are quite pricey. Finally, for those with more money than sense, Avanpost miniatures are absolutely beautiful resins that are financially ruinous, but are beyond gorgeous.

Rules

This is in no way exhaustive, but this offers some different price points and game sizes, depending on what you want from the period.

Pike and Shotte

Warlord Games’ offering for this period follows their usual, big-battle, Warmaster-esque style. Rulebooks are available for 28mm or the Epic range, but it is worth stressing that it works at any scale as long as you and your opponent agree on a consistent unit frontage. The Warlord rules suite isn’t always popular, but if you want a colour rulebook full of nice miniatures, it’s a good shout. Furthermore, I highly recommend their “The Devil’s Playground” supplement as an introduction to the period.

Pikeman’s Lament

Osprey Blue Book rule sets can be hit or miss, but Pikeman’s Lament offers a neat package for small-scale actions in the 17th century. Those familiar with Lion Rampant will be right at home here. Units are small, games are quick and it plays well. If you have fallen in love with a dynamic range like Bloody Miniatures, this presents a great option to use them.

Tilly’s Very Bad Day

Aside from the tongue-in-cheek title there is a lot to like here. First, the rules are free to download, so there is no cost to try them. They are sold as fast-play, and the few games I have played with it I thoroughly enjoyed. They handle small battles and larger engagements well enough. Since they are free, I recommend at least downloading them and seeing what you think!

En Garde!

A true skirmish ruleset, and another Osprey Blue Book. Small table, pointy swords, and elaborate insults are encouraged. My name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, prepare to die. However, what Inigo forgot to mention was the sheer number of modifiers required for dice rolls in this game. If you can get past that, there is fun to be had here.

Conclusion

The Thirty Years War is one of those conflicts that has something for everyone. The huge number of participants, the evolving tactics and the brilliant characters lure you in, and when you settle into it the amount of reading material and potential avenues for your collection just keep expanding.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.