Welcome back to my Road from Moscow, chasing the Corsican Fiend and his dwindling army away from the heart of Russia. Last time out, I chose an army and a theme: the Imperial Russian Army of the Great Patriotic War, specifically during the Great Retreat as they chased La Grande Armee west across the frozen plains. This time, I start turning this vision into a 28mm reality.

Picking Models

When I set off on this Historicals journey, I was sure of one thing: I did not want to use any metal models at all. I still have memories (and scars!) of my time in middle school, hacking away with an Xacto knife at metal Deathwatch marines to steal their bitz for a specialist Ork squad. It was not a good experience. Because I wanted these to be My Dudes, I was sure that the right answer would be to only buy plastic models and lovingly convert them to convey my vision.

Reader, I had no idea about the wide world of historical models.

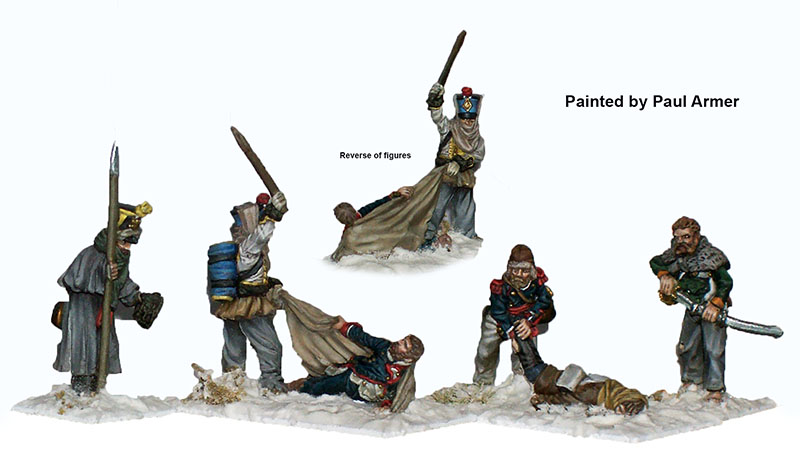

No matter what ideas I could have for a Dude, someone out there (probably the Perry brothers!) had already sculpted it far better than my clumsy hand swaps. Want grenadiers standing about in greatcoats? How about marching forwards? Frozen, bundled-up stragglers on their way west in the winter of 1812? Would you like dismounted cuirassiers, infantry, officers, or camp followers?

Especially in the 28mm scale, and especially for the Napoleonic Wars, Historicals are such an integral part of the wargaming experience that the breadth of available miniatures is spectacular. While each manufacturer typically has a slightly different aesthetic, they will usually play nice together. Don’t be afraid to mix and match styles and manufacturers as Lenoon has done below! With typical prices hovering around $1 per model, you have a lot of room to experiment before the cost really stacks up. It is simply much more practical to collect and paint a variety of historical miniatures that catch your eye than it is to start from basic plastics and try to convert them into Your Dudes.

My First Purchase

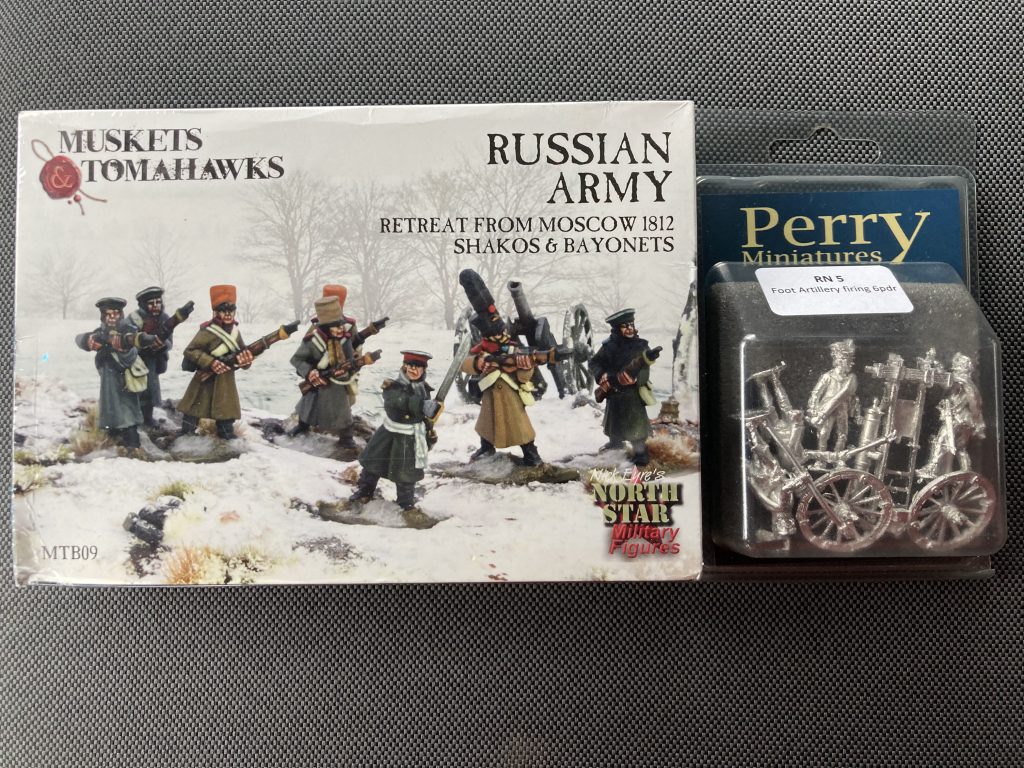

Armed with a lingering discomfort around metal models, I schlepped myself to the FLGS to peruse the Historicals section. There, tucked between the Warlord Games Zulu starter box and the Bushido cards, I found (nearly) exactly what I was looking for – a box of very cold-looking Russians.

Not content to leave well enough alone, the manager of my FLGS also talked me into buying a cannon for the force. While they didn’t have any greatcoat-clad Russian artillerymen in stock, I think that a decent mix of greatcoat and jackets will look better on the tabletop than a grey-brown mass. Splashes of green jackets will also help identify the army as more clearly Russian, and let me use this excellent painting guide as a jumping-off point for my color scheme until I’m a little more comfortable in the 19th century. And speaking of paint schemes…

The Uniform Myth

There are two contradictory truths in the world of Napoleonics. The first is that there is an incredible amount of in-depth research about the colors, buttons, hats, coats, and accessories that the soldiers of each unit in each country’s army wore. The second is that it is impossible to know with any kind of certainty the precise colors, number of buttons, or even type of hat that any individual soldier or company would have worn. There are a few reasons for this:

First, the Napoleonic Wars happened well before the Industrial Revolution reached Russia. The vast majority of Russian textile factories relied entirely on manual labor well into the mid-19th century. Even if we assume that every unit across the Imperial Russian Army was outfitted at the same time and to the same specifications, there would have been enough regional variation in cloth, dyes, processes, and even individual craftspersons that a consistent green was impossible.

Second, the Imperial Russian Army was not, in fact, outfitted at the same time and to the same specifications. Units were constantly being recruited from the farms and villages of the Empire, and the standing orders regarding their uniforms and kit were changing almost as often. In the years immediately preceding the winter of 1812, the uniform was changed in November 1807, December 1807, July 1808, April 1809, June 1809, February 1811, September 1811, and January 1812. The logistics of the time often did not allow for standing units to update their uniforms to new specifications, even if the commanding officer wanted to.

Finally, I am 200 years removed from the events that I’m trying to represent on the tabletop, and with that distance comes loss of detail. While there are plenty of excellent sources that condense the majority of the research into an easy-to-use format – Osprey is the most famous collection of these – there is still plenty of debate about some of the finer points. The Osprey on 1799-1814 Russian infantry briefly acknowledges the controversy surrounding the kiwer shako that was adopted in 1812, but fails to sum up just how wild it is.

The brief background: it’s widely accepted that as of 1 January 1812, the Imperial Russian Army discarded the cylindrical, flat-topped shako that had been issued and adopted a new design, called the kiwer. This new design flared from the base to the top, and the top had a transverse indentation in it, giving us something that vaguely resembled a saddle. This is accepted to the extent that the Perry Miniatures plastic box of Russian infantry includes cylindrical and kiwer shakos, and the instructions call out the kiwer as appropriate for 1812 onwards. HOWEVER, upon examination, kiwer is actually just the Russian word for shako, and I’ve seen compelling arguments that the “altered design” of the shako is just what a cylinder of felt and leather would look like after a year or two on campaign.

Was the kiwer shako actually a new pattern that was widely adopted by the Imperial Russian Army? Would regiments raised in the St. Petersburg inspection wear a slightly different green than those raised out of Yekaterinburg? Would a Russian nobleman, charged with raising a regiment, show off his wealth by springing for silver threading instead of plain white in the shako cords that his serfs were issued? Who knows! 200 years later, we’re lucky if we have contemporary sources that aren’t obviously lying about the height of their/enemy soldiers, depending on how the latest battle went for everyone!

All this is to say that it’s essentially impossible for us to paint our little toy soldiers “historically accurate.” As long as you have the broad strokes right – the Russians mostly wore dark green, the British wore red, the French wore blue, etc – paint with what you’ve got! As long as you’re happy with the results, you did it right.

I Played a Game!

Remember the FLGS manager that talked me into the extra cannon before I got sidetracked? Well, I strong-armed him into teaching me how to play my first ever Napoleonic game! Specifically, he treated myself and another new player to a demo game of Blucher with 15mm miniatures, from a variety of manufacturers. I took a small force of Russians against my opponent’s French. And reader, did it ever feel good.

What struck me as I was playing the game was how much it felt like my (admittedly childish) idea of a Napoleonic battle should. Units of cavalry felt zippy and disruptive, but ultimately melted away before doing serious damage. A cavalry skirmish formed on my right flank, my Cossacks running interference against my opponent’s much more fearsome Cuirassiers. Artillery barrages from the fearsome Russian cannon devastated his line before my Grenadiers marched uphill against the weakened right flank, weathering fire of French skirmishers before closing into melee. Stalwart lines of Musketeers formed on the left flank, trading volleys of lead then retiring in good order to prevent their destruction.

Blucher is a very simple system – despite this being a demo game, we players were pretty much off on our own by the third turn – but the design is tight. From a very simple set of rules, the feel of the period naturally follows. The action economy forces you to make hard choices about what you need to do right now, because there’s no guarantee that you’ll be able to activate another unit. You know that you need to form your units into square because the enemy cavalry are coming over the hill, but if you spend your precious orders to do that, the center of your line is certainly going to give in. Which one matters more, Field Marshal??

Recommended Reading

This month’s* recommended reading is A Short History of Russia, by Mark Galeotti. If you don’t know anything about the history of the country, this is an excellent place to start. The book begins with the (at least) semi-mythical origin story of Russia as a united nation, when the natives “invited” the Rus tribes of Vikings to be their leaders; and continues up to the present day, touching on the turbulent fall of the Soviet Union and the strongman that was able to rise up from its ashes. Galeotti contextualizes each major event in the country’s history in terms of what he terms the “national myth” – how the people as a gestalt think of themselves and their nation – which helps an outsider to understand a culture that is familiar, but with distinctly foreign quirks. I would love to read a book with the same premise about the United States or United Kingdom, frankly.

*Month…ish

It’s safe to say that my first taste of Napoleonic gaming left me wanting more. I’m very much looking forward to putting my models on the table, but I’ll need to paint and base them first…

I’ll admit that I got a little distracted this time – this was supposed to be the hobbying article, but I found a soapbox. Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more