The campaign in Burma and the conflict in the Far East are often under-discussed parts of World War Two and are frequently under-represented in wargaming despite the many fascinating events that took place there. Even at the time it was rarely covered by the press, leading General Slim, the commander of the British 14th Army that fought in that theatre to call his soldiers “The Forgotten Army”, a nickname that has stuck to this day. Composed mostly of colonial troops from India and Africa, the story of the 14th Army is an extremely interesting one. This article isn’t about them, however, instead it’s about an army they fought against that is discussed even less in most of the world: The Indian National Army.

Formed from Indian prisoners of war captured by the Japanese, and later Indian volunteers from Singapore, the Indian National Army fought alongside the Axis powers against the British Empire in a war for India’s independence. Under the command of the charismatic Subhas Chandra Bose, the INA would fight as part of Operation U-Go, the attempted Japanese invasion of India in 1944, including the brutal battles of Imphal and Kohima, referred to by some historians as the “Stalingrad of the East”.

Paradoxically, despite their willing associating with Nazis and fascists, the INA strove to break down caste and religious divides in India, even raising an all-female regiment. Ultimately, after the failure of Operation U-Go, the INA would suffer from significant morale issues and would collapse after Japan’s surrender. However, despite their failure the INA would prove to be a significant factor in India gaining its independence, though perhaps not in the way its members had imagined.

The First Indian National Army

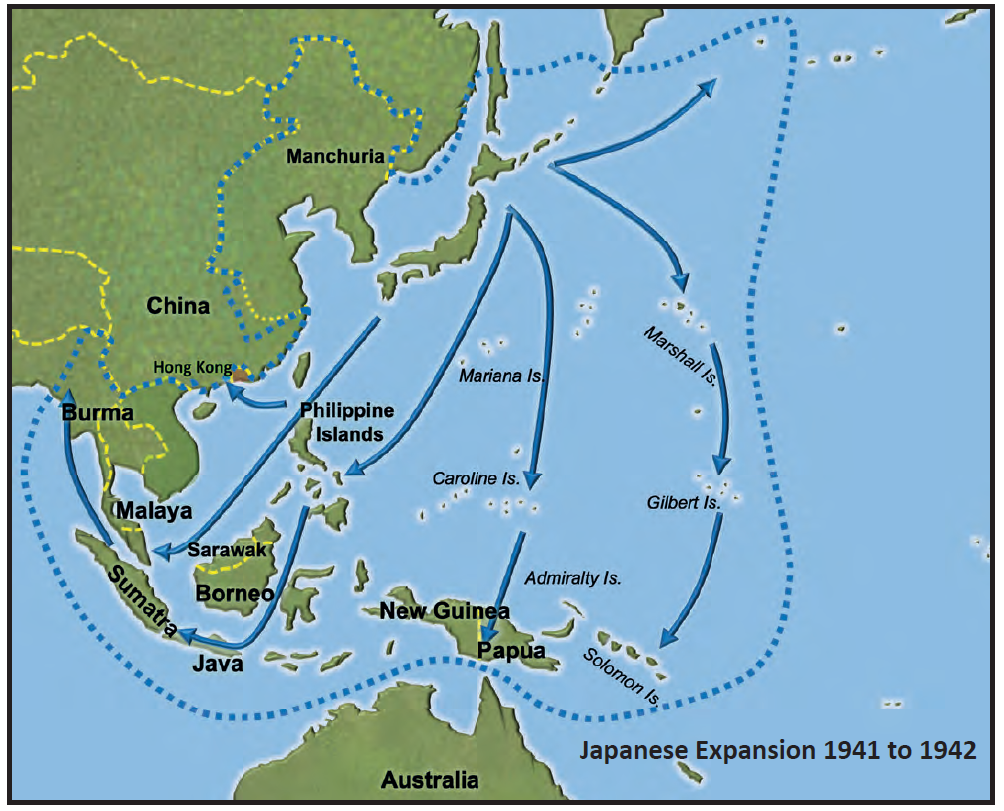

The story of the Indian National Army’s foundation begins with Major Iwaichi Fujiwara, the self-described “Lawrence of the Indian National Army”. As part of a group named F-Kikan after himself, Fujiwara was tasked with fostering and assisting independence movements in British India, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. This was part of the Japanese ambitions for a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a union under Japanese leadership in opposition to Western imperialism. For the most part, this was merely a propaganda campaign, hiding Japan’s own imperialist ambitions under the guise of benevolent liberators. It was so successful in fact, that many locals welcomed the arrival of Japanese forces until they witnessed their cruelty firsthand.

Despite primarily being intended as a propaganda tool, F-Kikan’s assistance in establishing various resistance and independence movements in Asia would have a significant impact on those countries, particularly after the war as the imperial powers sought to re-establish control over their old colonies. In some cases these movements would even end up turning on the Japanese, such as in the case of the Burma Independence Army who ended up joining the British to cast out the Japanese armies they had once fought alongside. In other cases, such as in Indonesia, resistance movements established to oppose Japanese occupation would end up working alongside former collaborators in fighting for independence from their colonisers after the war.

Fujiwara’s greatest success was most likely the Indian National Army, and the first concrete step towards its foundation began with the capture of the 1/14th Punjab Regiment in December 1941 after the British defeat at Jitra. Accompanied by Giani Pritam Singh Dillon, a Sikh missionary who had previously been involved in the Ghadar Mutiny against the British Raj during the First World War, Fujiwara met with Captain Mohan Singh of the 1/14th Punjab and convinced him to work alongside the Japanese. Mohan Singh was initially distrustful of the Japanese but was won over by Fujiwara’s sincere belief in the cause and the many concessions he offered. Foremost among these were that the Indian National Army should operate independently of the Japanese military and that Indian prisoners of war should be treated favourably regardless of whether they agreed to join the INA. Japan would break both of these promises before long.

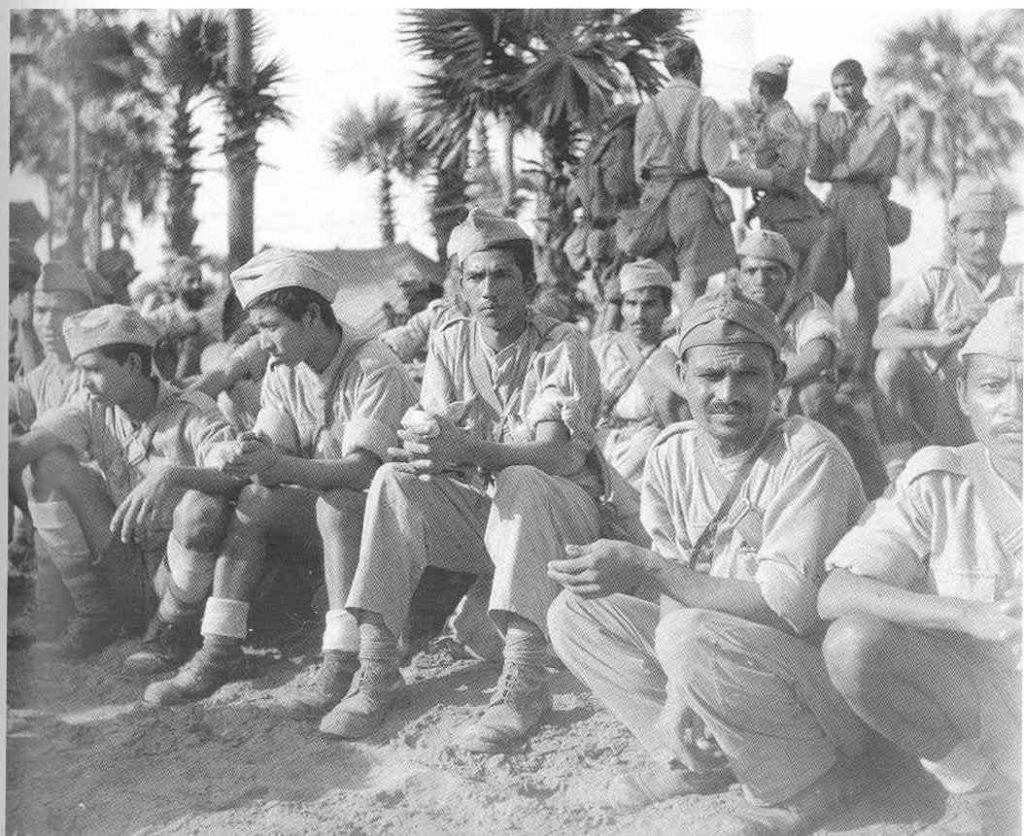

Even before the official formation of the INA, Singh began recruiting from among Indian prisoners of war. These volunteers numbered nearly 2,500 and were given armbands bearing the letter F to show their loyalties. Even this early on, Singh made significant changes to how the soldiers were organised compared to how they were organised under the British. The British Indian Army had instituted policies of segregation between those of different castes and religions designed to encourage rivalries and conflict between these groups, but Singh worked to establish a joint national identity by using common slogans and a common (instead of caste-based) kitchen.

This nascent army would be bolstered in February 1942 by the capture of roughly 45,000 Indian soldiers during the fall of Singapore. Two days later, they were addressed by Fujiwara and Singh at Farrer Park in Singapore. Fujiwara told the assembled prisoners of Japanese plans for an Asian co-prosperity sphere and their intentions to raise an army to fight for India’s independence, promising to treat them as friends and allies instead of PoWs. Singh’s speech was much shorter and resonated deeply with the troops, simply inviting them to join the Indian National Army and fight for an independent India.

First, however, the gathered troops were officially handed over to Japanese authority by Colonel Hunt of British Malaya Command. After the war, this action would be referenced by members of the INA in their defence against charges of treason during the Red Fort trials, arguing that by handing them over to Japanese command Hunt had effectively nullified their original oaths to the King-emperor. From that perspective, the Indian soldiers had never betrayed the Empire, instead the Empire had betrayed them.

Leading up to the official formation of the INA in May 1942, Indians in occupied Singapore, both PoWs and civilians, received fairly lenient treatment by the Japanese forces compared to the horrors they inflicted upon others. White British officers and non-Indian PoWs were treated horrifically, and in the months that followed the fall of Singapore the Japanese would kill roughly 50,000 Chinese civilians during the Sook Ching massacre. In many cases, the Japanese would go against their agreement to treat Indian PoWs fairly regardless of whether they joined the INA, not only providing incentives to those who joined but also punishing those who refused by depriving them of food and medical aid and taking away officers to be beaten.

In Spring 1942, Fujiwara was replaced by Colonel Hideo Iwakuro who quickly began to break the promises made to Singh. The Japanese army failed to give the INA the freedom to operate independently that they had been promised, using them primarily for propaganda, espionage and sabotage. Singh felt like the assurances he had been given by Fujiwara had been broken, and this was exacerbated by the Japanese failure to act on resolutions made by the Indian independence movements at the Bangkok Conference. In November, Singh refused to send a planned group of soldiers to Burma and in December, following the arrest of one of his officers in his own home in Singapore, Mohan Singh gave orders for the INA to be disbanded and was quickly arrested. Many of the Indian troops chose to revert to their status as PoWs, and a great number of those were subsequently sent to work on the infamous Burma “Death Railway”.

The Indian National Army looked like it was all but finished before it had really had a chance to come into its own. A new leader was needed to revitalise the failing army and there was only one clear choice for that role, the former president of the Indian National Congress, and the man Singh had suggested as the ideal leader for the INA, Subhas Chandra Bose.

Subhas Chandra Bose

Bose’s political career began in 1921 when he returned to India after studying at the University of Cambridge to join the Indian Civil Service, before quitting despite his excellent results as he felt the job was in conflict with his nationalist ideals. Immediately on his return he managed to arrange an interview with Mahatma Gandhi, and the two clashed immediately in a precursor to their later conflicts. Bose considered Gandhi’s goals to be unclear and they disagreed on the proper way to secure India’s freedom. While Gandhi favoured a peaceful transition of power through non-violent protest, Bose was unafraid of conflict and favoured authoritarian government, saying during his travels in Europe in the 1930s that India needed a cross between Socialism and Fascism if it was to gain its freedom.

Bose would quickly become involved with the politics of the Indian National Congress, starting out by founding the newspaper Swaraj, and then commanding the Bengal Volunteers Corps in a preview of his future role with the INA. He clashed again with Gandhi on this and many other matters throughout his life, but it’s also clear that the pair held a deep respect for each other, with Bose later naming Gandhi “the Father of the Nation”.

In 1938, Subhas Chandra Bose was elected president of the Indian National Congress, but he was politically outmanoeuvred by Gandhi and forced to resign the next year. When war broke out, India was brought into the war without the consent of its elected leaders, and the response to that within the Indian independence movement was highly varied. Many were supportive of the fight against the Nazis, though they felt that it was hypocritical of the British government not to give them a choice in the matter and to refuse to discuss independence until the war was over.

Bose, on the other hand, began to organise a campaign of mass civil disobedience to protest the decision to declare war without consulting India’s leaders, beginning with a protest in Calcutta that saw Bose arrested and imprisoned. Following a seven-day hunger strike he was transferred to house arrest, which he escaped in January 1941. His guide, Bhagat Ram Talwar* helped him make his way to the Soviet Union, but he was unable to convince the Soviets to support an uprising in India. Instead they sent him to the German Ambassador in Moscow, who helped him travel to Berlin where he would establish the Special Bureau for India.

*Talwar has the accolade of being World War 2’s only quintuple spy, working for Germany, Japan, Italy, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain.

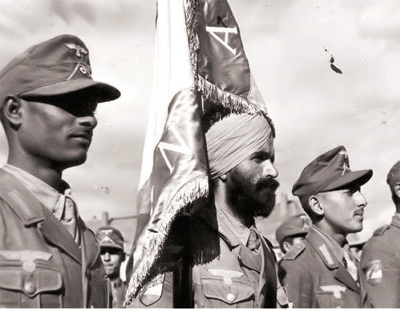

Bose’s goal in Berlin was the establishment of a force recruited from Indian prisoners of war captured during the North Africa campaign, intended for use in a planned German invasion. This was the Indische Legion, also known as the Free India Legion or the Tiger Legion. Roughly 4,500 strong at its peak, the Indische Legion was founded under rather generous terms, receiving the same training and equipment as a regular German unit while remaining separate from the German command structure and only being allowed to fight in India or in self-defence while training in the Netherlands and France. The Legion saw limited action during the war, mostly being used for anti-partisan operations, until they were captured trying to make their way to neutral Switzerland after the German defeat was obvious. It was the Indische Legion who gave Bose the title of “Netaji” (meaning “Respected Leader” in Bengali), a title that would follow him for the rest of his life.

In Italy, another force would be formed from Indian PoWs, the Battaglione Azad Hindoustan, which included a platoon of paratroopers. This unit would never see combat, however, and were disbanded in November 1942 after they mutinied upon receiving news of the Axis defeat at El Alamein.

Interestingly, the Special Bureau for India that Bose founded would end up becoming a haven for anti-Nazis within the German government, and it was used by Adam von Trott du Solz (one of Claus von Stauffenberg’s collaborators in the plot to assassinate Hitler in July 1944) as cover for his anti-Nazi activities. However, this doesn’t exactly let Bose off the hook for his collaboration with the Nazis as there’s no evidence he even knew that the Bureau was being used in this way. Von Trott certainly didn’t trust Bose enough to take him into his confidence, as Bose had shown he was perfectly willing to work alongside Hitler, going so far as to ask Hitler to remove passages from Mein Kampf denigrating Indians and publishing an article in the journal Angriff calling Indians ‘true Aryans’ and mentioning that the Swastika was originally an Indian symbol.

In February 1943, unhappy with the level of support he had received from Germany, and believing that the Germans saw the Indische Legion as a propaganda piece rather than a legitimate combat force (he was most likely correct as Hitler later called the Indian Legion “a joke”), Bose boarded a submarine and travelled to Japan. During this time he was involved in the only civilian transfer between two submarines belonging to two different navies during World War 2.

Meanwhile in Singapore, Rash Behari Bose (no relation) was struggling to re-establish the Indian National Army after the resignation of Mohan Singh and much of the rest of the INA’s leadership. Many of the Indian prisoners of war, having been returned to PoW camps, made it clear that they would only rejoin the INA if it was led by Subhas Chandra Bose.

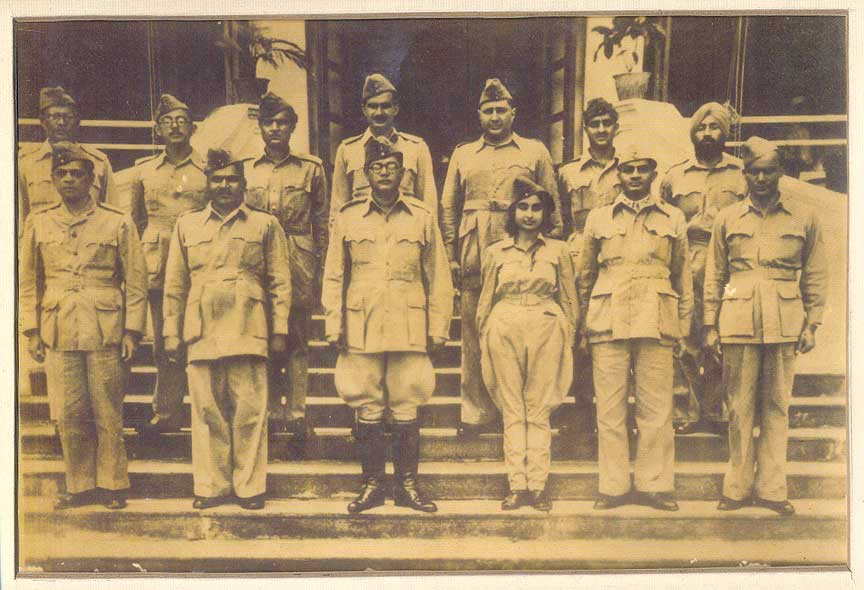

In July 1943, Bose received control of the Indian National Army and he immediately began to rebuild it. Recruitment swelled, not just from captured PoWs but from the Indian civilian population in Singapore and the surrounding area. Bose’s new Indian National Army was even more progressive than its predecessor. Not only did he eschew the boundaries of religion and caste when forming regiments as Singh had, but he also created a separate regiment for female volunteers, the “Rani of Jhansi” regiment, based on requests from many local Indian women who wanted to take up arms and fight for a free India.

The Second Indian National Army

On the 21st October 1943, Subhas Chandra Bose helped form the Provisional Government of Free India (or Azad Hind) – with himself as head of state – and they declared war against Britain and the United States two days later. The government had its own currency and courts, and was intended to take control over any territory in India that was captured by the Japanese. In December 1943, the Japanese handed over official control over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, ironically renamed “Shaheed” and “Swaraj” (meaning “martyr” and “self-rule” respectively). This was the only real territory that Azad Hind had control over, and even then it was mostly theoretical with the true power in the hands of the Japanese police force.

During Bose’s only visit to the islands he was kept away from the population by the Japanese authorities who thwarted various attempts to contact Bose and inform him of the horrors the islanders were suffering under the occupation, including the imprisonment, torture and killing of many Indian nationalists. In total, around 2,000 people are thought to have died as a result of the occupation, roughly 10% of the islands’ pre-war population.

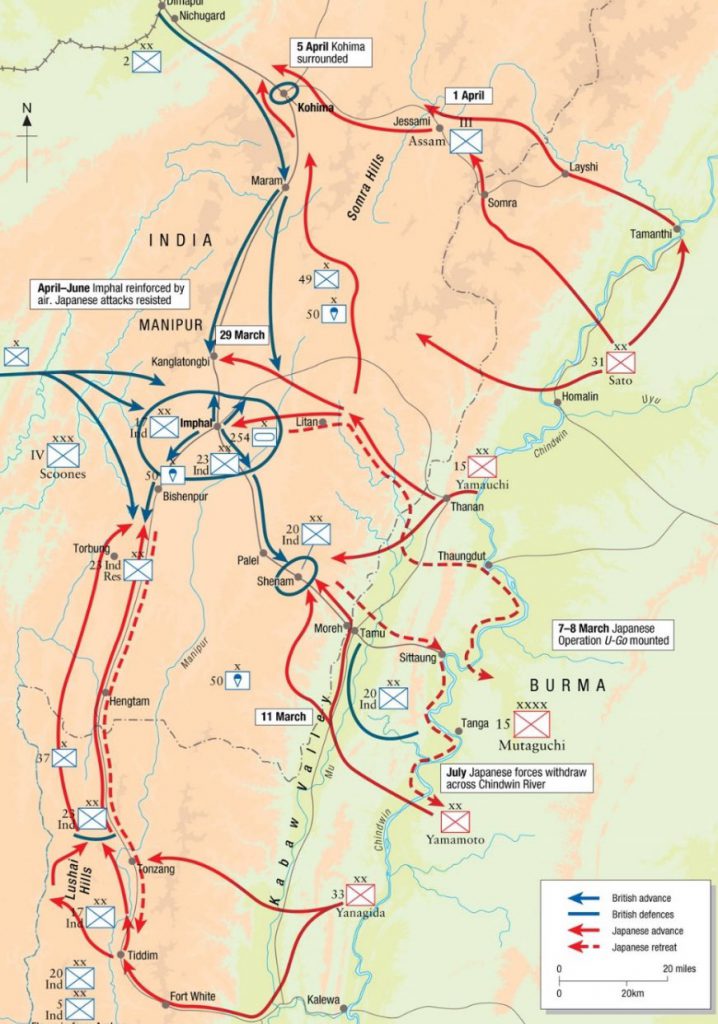

The renewed Indian National Army would first see action in March 1944 as part of Operation U-Go, the Japanese offensive towards Manipur that aimed to open the way into India. The initial plan was for the INA to be used primarily for espionage and propaganda during this offensive, but Bose managed to succeed where Mohan Singh had previously failed, convincing the Japanese to treat the INA as a proper allied army. The requirement for espionage was met instead by the INA’s Bahadur Group, a special services unit attached to Japanese forces to spread propaganda and act as scouts. The plan was that once the Japanese broke through the British lines at Imphal and Kohima, the INA would travel further into India and act as a guerilla army, living off the land and captured British supplies. That way, even if Japan lost the war, the INA could inspire a popular uprising and make it extremely difficult for the British Empire to retain control of India.

Unfortunately for them, the British Indian Army they faced in 1944 was not the same one that the Japanese had swiftly defeated in 1941-42. They were better trained, better equipped, better supplied, and most importantly they were prepared for the Japanese style of offensive. Even if Operation U-Go had succeeded however, the INA may not have had the success in India they anticipated. Under the new General William Slim, the attitude among the British Indian Army had changed significantly in the years since the INA’s formation, partly due to the highly successful Jiffs (Japanese-Indian Fifth-columnists) propaganda campaign. Additionally, following the arrest of 100,000 people including Congress leaders resulting from the 1942 Quit India movement, in which Gandhi and many others who had tentatively supported the British war effort began a campaign of mass civil disobedience, the Indian independence movement was in poor condition and may not have been able to provide the assistance Bose expected.

The INA’s 1st Division was the only one to fight as part of Operation U-Go, consisting of four Guerilla Regiments, each named after a major figure in the Indian independence movement (Subhas, Gandhi, Azad and Nehru in order). The 1st Battalion of Subhas Brigade joined the diversionary attack at Arakan, while the rest of 1st Division took part in the main offensive at Imphal and Kohima. Here, over the course of three months, the Japanese army shattered against the British defences and any hope of breaking into India was lost. The INA had performed well given its lack of heavy weaponry, but as they began to retreat into Burma it became clear that they were being expected to die only to retain Japanese territorial gains. They began to suffer severe morale issues and faced numerous desertions.

They’d spend the rest of the war in retreat, with a couple of notable actions before the end. In February 1945, two battalions of the 4th Guerrilla Regiment would attempt to halt the British advance at the Irrawaddy River in what was the longest opposed river crossing of the war. Then, at Mount Popa the 2nd Division fought alongside the remnants of the 1st and 4th Guerrilla Regiments using guerilla tactics, but following additional desertions they were forced to retreat and eventually surrendered to the British forces.

The Rani of Jhansi Regiment

While they saw little action during the war, it’s also worth discussing the role of the all-female Rani of Jhansi Regiment in the INA, as not only do they have a fascinating story in their own right but they also shine a light on Bose’s true beliefs. While you might expect the regiment to have been a simple propaganda tool, or perhaps a desperate attempt to round up as many soldiers as possible, it certainly seems like Bose had far greater plans for them. As a symbol for this new regiment, Bose chose the Rani of Jhansi, a famous queen who fought in the 1857 revolt against the British, using her as an example of the role he saw for women in the struggle for India’s freedom. In contrast, Gandhi’s vision for women was a submissive and non-violent one, embodied by Sita, the heroine of the Hindu epic Ramayana, who follows her husband into exile and struggles to convince him of her fidelity after she is abducted and rescued.

The regiment’s training camp was opened in October 1943 and women from all backgrounds rushed to join, mothers and daughters alike leaving behind their families to fight for a free India. The women not only received military training to the same standard as the men, but a general education as well, covering history, geography, and ironically a seminar on ‘the great men of the world.’ A number of them would also receive nursing training. For many lower class women this was the first proper education they would receive, and for many upper class women this was their first time outside of the restrictions of Purdah, a culture of social segregation of women.

To lead the regiment, Bose chose Lakshmi Swaminathan, a doctor originally from Madras with an unusually progressive upbringing. She would be known from then on as Captain Lakshmi and Bose also appointed her Minister in Charge of Women’s Organisation in the Provisional Government of Free India. After the war she married fellow officer Prem Sahgal, who had led the INA troops during the battle at Mount Popa.

On 30th March 1944, the regiment had its first passing out parade with roughly 500 soldiers. Despite their military training, their first assignment was the caretaking of wounded INA troops and the women were rightly frustrated, presenting Bose with a petition signed in blood calling on him to send them to the front lines. Bose relented, ordering a group of them to be given advanced guerilla training and sending a contingent to Maymyo with plans for them to join the rest of the INA as a guerilla army inside India after the expected fall of Imphal.

With the disastrous failure of Operation U-Go, however, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment were left to once more assist the wounded on the retreat back to Singapore. Bose marched alongside them for twenty three days as they travelled under cover of darkness, beset by attacks from local guerillas and enemy aircraft. With his feet covered in blisters, Bose refused to abandon the regiment, even telling the Japanese to “go to hell” when they offered him a car to take him safely back to Singapore. He last saw them on 14th August 1945 when the women of the regiment performed a drama on the life of their namesake.

The Post-War Legacy of the INA

With the war lost, Bose made new plans for India’s independence, seeking allies once more in the Soviet Union. On 18th August 1945, Subhas Chandra Bose died of third-degree burns after the plane taking him to the Soviet Union crash-landed. He left behind a complicated legacy; seen as a hero by many in India to this day, the circumstances of his death sparked numerous conspiracy theories and legends. Despite the praise he deserves for his progressive views around women and equality and his willingness to put them into practice, it’s impossible not to criticise him for his willing collaboration with fascists. Bose is also commonly viewed as a hero by Hindutva nationalists, despite the fact that many of his beliefs were diametrically opposed to their fascist quest to create an India for Hindus.

With the war over, and without their leader, the captured soldiers of the Indian National Army faced trial for treason, placing them directly in the public eye as the Indian independence movement regained momentum. Seen as traitors and collaborators during the war, the attitude towards the INA was now much more friendly, and the Indian National Congress stepped in to provide defence. The trials took place at Red Fort starting in November 1945, with the first three defendants sentenced to deportation for life for the crimes of ‘waging war against the king’, murder, and abetment to murder. These sentences were never carried out, however, as India was rocked by protests.

Across the British Empire, Indian soldiers began to mutiny. Many had signed up to fight against the Axis and were now being used to maintain control over an Empire they didn’t believe in. During the trials, over 10,000 sailors in the British Indian Navy mutinied, followed by additional mutinies across India including in Madras and Jabalpur. The Royal Indian Air Force also went on strike at the same time. In another example of mutiny, 600 Muslim soldiers from a Gurkha regiment assigned to the Dutch East Indies joined the local Indonesian resistance and fought against the British. Only 75 of them would live to see Indonesia gain its independence.

The furor around the Red Fort trials and the disobedience in the Indian army inspired by the INA played a significant role in the fight for independence, with Gandhi observing that “the whole country has been roused” as a result of the trials and the associated movements. In this way the INA had a greater effect in defeat than it did during the war, though the independence they gained did not take the form they likely imagined. In 1947 the British Partition of India would split members of the INA between India and Pakistan. The partition, decided in the House of Commons, split the nations based on religion, reigniting the religious divisions the INA had tried to avoid . The resulting violence caused the deaths of 1 million people and between 14 and 18 million were displaced from their homes.

After partition many members of the INA went on to take positions in politics. Forced out of his home in what became Pakistan, Mohan Singh formed a private military in India named the Desh Sevak Sena with its own women’s wing, and would later serve in the upper house of the Indian Parliament. Captain Lakshmi would become a founding member of the All India Democratic Women’s Association in 1981, going on to be nominated by a coalition of four leftist parties as a candidate in the 2002 presidential elections.

Modelling the Army

Surprisingly for such an under-discussed army, finding models to represent the INA is relatively easy. Initially when starting this project I picked up a box of Imperial Japanese and British 8th Army Infantry, but as I looked into the history some more I found that the INA were only equipped with their old British uniforms and weapons. In fact, while the British 14th Army would transition to their new jungle green uniforms by the time they faced the INA, the INA would retain the old khaki uniforms, represented pretty much perfectly by the Warlord Games 8th Army kit. It’s worth noting that the Warlord Games Japanese models are notorious for their racist head sculpts, I bought my box before I learned that, but I’d recommend looking at models from other companies if you want to run Japanese forces alongside the INA.

Here’s my first infantry squad, organised according to the platoon rules in the Far East supplement for Chain of Command. I’ve got a second squad with the same loadout unpainted, and after that I’ll build an officer and a third squad with just rifles to complete the platoon. I’ve used a mixture of the Sikh, Muslim and helmeted heads from the 8th Army box within each squad, as a way of representing how the Indian National Army broke down religious divides.

I used the following paint scheme with mostly Vallejo paints, with the occasional Citadel paint mixed in:

- Uniform: Iraqi Sand

- Webbing/Helmets/Gear/Socks: Khaki

- Metals: Iron Warriors or Leadbelcher

- Boots: Corvus Black

- Skin: A mixture of Burnt Umber and Medium Flesh, plus varying browns and skin tones. I didn’t try to replicate a specific skin tone, instead I used various mixtures of paint on different models to try and further the idea that they come from all over India.

I washed with Agrax Earthshade on the majority of the model, and Reikland Fleshshade on the skin.

When I started this army I built an additional squad in Japanese uniform, mostly because I’d bought the box before I found out the INA only wore their old British uniforms, but also as a way to get some practice painting using some models I didn’t care about as much. These models are extremely ahistorical, but I’ll probably use them in Bolt Action as veteran infantry or other elite models just to differentiate them from the other squads. I also built a light mortar team to go alongside them, as the INA did have limited access to mortars, though they probably wouldn’t have used the Japanese kind shown here. For their paint scheme, I used mostly Japanese Uniform with Green Grey for the socks and Flat Brown for the straps.

The INA had limited access to equipment, and so if I do decide to get any tanks or artillery for the army I’ll be running them as allied Japanese forces. In terms of heavy weaponry, each company had access to six Boys anti-tank rifles, six Bren guns and six Vickers machine guns. I’ve got a Bren gun built into one of the squads, as well as a Boys anti-tank rifle on its own. Both of these weapons come in the 8th Army box, and I’m planning to pick up a Vickers machine gun and add it to the force soon.

Finding models to represent the Rani of Jhansi Regiment is unsurprisingly a lot harder, though I did manage to find a way that was good enough for me. There’s very few companies that specialise in historical female miniatures, but Bad Squiddo Games does some very good models, including a women’s soviet army, as shown in HardyRoach’s article on his Soviet Women’s Rifle Platoon. I’ve been using models from their British WW2 range as many of the Ranis were trained as nurses and so I’ve got a medic to represent that aspect, but they also bore weapons and the Women’s ATS with rifles from Bad Squiddo serve as a good approximation, though obviously the uniform isn’t an exact match. Rules-wise, I’ll probably be using them as scouts, though I might pick up another pack or two at some point so I can run them as a full sized infantry squad.

Representing the Army

Things understandably get a bit more difficult if you want to actually play some games with your Indian National Army models, though there are still a couple of options for doing so. If Bolt Action is your thing, there are rules for the INA in the Empires in Flames book, but they only exist as a single unit for the Japanese army which for some reason doesn’t come with any theatre selectors to allow for their use. The unit comes as a 5 to 10-man Inexperienced squad with Green that doesn’t benefit from any of the Japanese army rules, with the option to give them a light machine gun or make them Shirkers to get a hefty discount. As a result, the INA probably works best in Bolt Action as a small part of a larger Japanese force, though you could probably run a whole army using the Japanese rules or maybe even use the rules of another nation, like the Greeks or Communist Chinese, that have a focus on mobility or guerilla warfare.

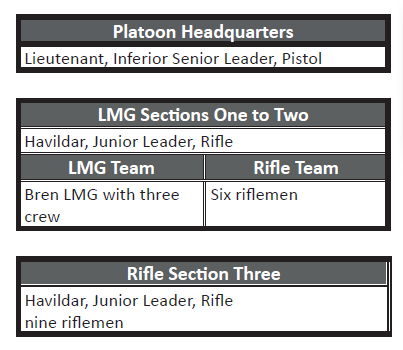

If on the other hand you prefer Chain of Command, you’re in luck. The new Far East book (which we reviewed earlier this week here) contains rules for an Indian National Army platoon that are quite flexible, able to use the support list of any other Japanese platoon at a slight premium and using the British Five Rounds Rapid national characteristic in place of the Japanese characteristics. The platoon consists of an Inferior Senior Leader in the platoon hq, and three ten-man sections, two of which have Bren LMGs. They also have the ability to take the special forces Bahadur Group as a support option, which aren’t represented by models but instead provide a once per game ability that has a chance of making a single enemy unit pinned or even making them surrender.

Conclusion

Part of why I’ve invested so much time on this project and researching this army is because it is obscure and there isn’t much information about it, at least not in the rulebooks for most wargames. If I’d decided to play a British army I could have just picked up a starter set of models, painted them in the standard colour scheme and started playing. Instead, because I had to research uniforms and equipment for the army I ended up learning so much more. I learned about their struggles and their sins, and I understand so much more about an under-represented part of history because of it.

In the process, I also learned a lot more about my own country, Britain, and its Empire, and I gained a better understanding of why someone might choose to side with the Nazis over the British. I wholeheartedly recommend Lupe’s excellent article on why we play the “baddies” for further discussion around the nuances of wargaming in World War 2 that touches on similar topics. In finding out about the kind of British actions that motivated the INA I learned more about the Bengal famine and how the British scorched earth policy against the Japanese and Churchill’s refusal to send aid played a significant role in the famine that claimed the lives of between 800 thousand and 3.8 million people. In learning about the aftermath of the war in the Far East I also found out more about the Malayan Emergency in which British forces sent 400,000 ethnically Chinese people into concentration camps, this being the same group that had been targeted by Japanese forces in the Sook Ching massacre during the war.

So my advice to you, if you’re looking to start a new historicals army, is to find an army, a nation, or a regiment that you don’t know much about and in the process of building that army learn about them. Maybe that’s the Indian National Army, or maybe that’s something else. Find out about their history and the history of those associated with them. Remember the lives and the stories of people whose names you never would have learned otherwise, and when you sit down across the table from your opponent try and find the time to share those stories. That way we all learn a little bit more about the history of our world, the good and the bad alike.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.