Lenoon: Proliferation of scales, rule sets, styles of play, eras and everything else means that more than anyone else in mini gaming, Historicals players need to run good Demo Games. With a new Napoleonics campaign coming up in my local area, and loads of great rule sets there to try – and people to try them with – we’ve opened the floor to the Goonhammer Historicals team to teach you (and me!) how to run the perfect demo game.

Why are demo games important in Historicals?

Zuul the Cat: In the course of playing historicals it is inevitable that you will end up wanting to build, paint and play in an era that not many people in your gaming community play. The best way to get them to play that game is by running a demo game – usually with models you build & paint – and then hook them. The first hit is always free, as they say.

Ilor: For sure. And there’s one thing to make clear here – not every demo game needs to happen at a convention or gaming event with you teaching people you don’t know. Teaching one or two friends how to play a game counts as a “demo game” too, and it’s just as important to get that right as it is a big public event (because you want your friends to get hooked so you’ll have someone to play with!).

Wowshawk: Historicals also tend to be a bit niche within niche, and not as ubiquitous as the warhammers or x-wings, so the bar of entry is a bit higher. My experience at wargaming cons also shows that historical games aren’t that accessible, and walking up and chatting to people who are running a game can be daunting if it’s your first foray exploring historicals. I’ll focus on that a bit more, as it’s easier to introduce a friend or wargaming pal to a demo when you know their background, what games they’ve played and how much rules minutiae they can handle.

Thundercloud: If you aren’t willing to even demo it, why should other people be willing to buy, build and paint an army to play that game with you? Games that aren’t the big few (40k, AoS, maybe X-wing/Legion) are a risk in terms of the investment of time and money and opportunity you are making (paint a 6mm Napoleonics army on an off chance or some 40k stuff that you will definitely find people to play), and gaming is a social experience. I remember I wanted Gates of Antares to get going in my local club, so I painted two 500 point armies and took them down there and ran games with different people for several weeks and it ended up with players.

Mugginns: I think it’s important (maybe?) to differentiate between a demo and a participation game. A demo, to me, is maybe a little smaller of a game that will take less time, and you have to explain every single thing and have a plan to move the game along. You also might be trying to sell people on the game.

A participation game is something that I think the players are more invested in – likely they’ve played the game before, want to play it at a higher level, and know a bit about the period. You’re putting on a game for people because you love it, and maybe you’re going to participate too.

Ilor: Mugginns’ bringing up “participation” game reminds me of something else that’s important to clear up: like most things trans-Atlantic there is a difference in terminology between how folks in the US and UK refer to these kinds of games. In the UK, a “demo” game is often just two people (who both know the game, and who may both work for the company that makes the game) playing the game while other folks watch. It’s a good way to show people the basics of how the game plays without having to actually teach the rules and expect players to use them. What we here in the US consider a “demo” (getting other people to actually sit down and play the game) is often referred to as a “participation” game in the UK.

Maybe it’s the American in me, but I never really saw the point of the UK-style demo games. If I’m interested in a game, I want to get in there and interact with the table and terrain and move dudes around and roll dice and blow shit up! Watching other people do it is snoresville.

What do you need to run a good demo game?

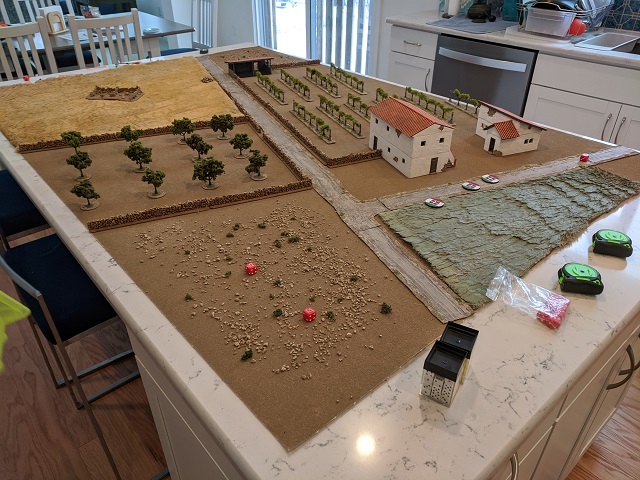

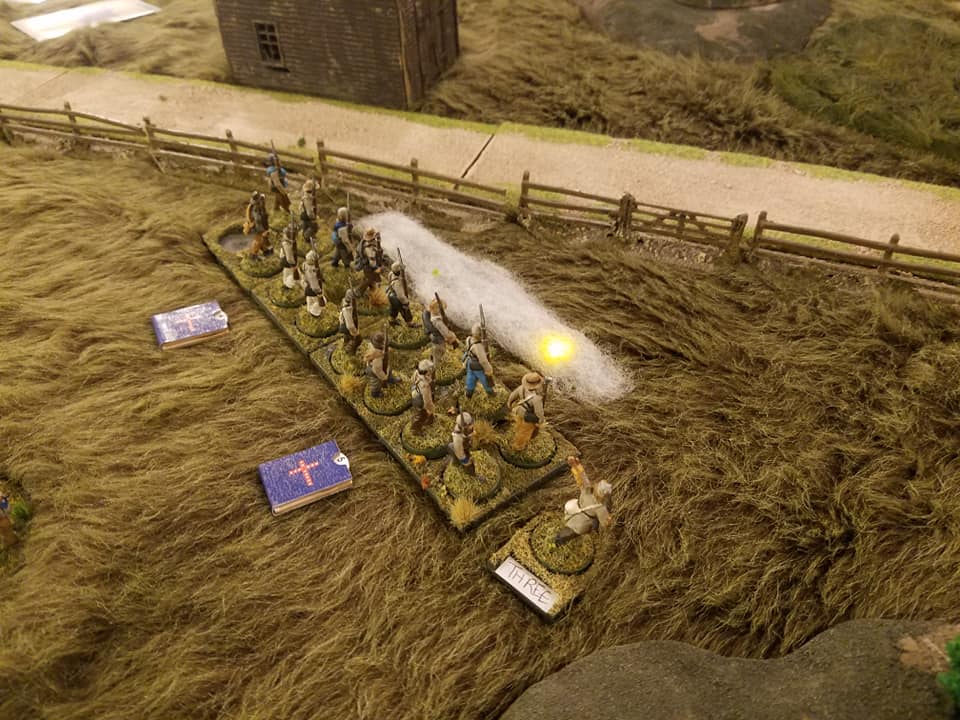

Zuul the Cat: I think it’s really a mixture of two things. First, if you want to run a demo game you should be doing it with fully painted and based models on a table with some nice terrain. You may be tempted to run demo games with gray plastic, but that is a mistake. The goal of the demo game should be inspiring people on how fun the game is and how cool it looks.

The second thing is that you want to let the person you are running the demo for win. No one is going to want to play the game if they get crushed during a demo. Make a small skirmish list but make the opposing sides a little stronger, make purposely bad moves, etc.

Wowshawk: The periphery of running public demo games is also important. Keep clutter at bay (no stacks of paper or messy coffee cups and beer glasses), print and laminate that quick reference sheet or unit card, make sure there’s enough dice and measuring tools handy. Specific range rulers and other game specific stuff can elevate the game as well.

Giving out demo games for a whole day is also tiring. Make sure you’re not the only one doing it or give yourself a half hour off now and again. If you’re at a con you also need to visit the traders to add to your backlog.

HardyRoach: I think it helps to thread a strong narrative. One of the strongest aspects of historical gaming is its capacity for really strong narrative play, and you want that to be front and center. It’s one thing to run a WW2 demo game where you fight over a village – but where is the village? Why is it an important strategic location? Is there a reason why one side or the other is invested in its defense/acquisition? For a similar reason, when picking forces, pick sides that have strong narrative ties. In the previous example you could just have Americans vs. Germans, but why not make it a French resistance force with American support vs. Vichy French with German support? Make it personal!

Thundercloud: You could make a powerpoint slide with bullet points out of this. And I imagine companies do designing their entry level products. Simple – teach the basic mechanics. Have play aids. Don’t add the weird stuff in. Well-presented – painted miniatures and terrain. Friendly – be nice and welcoming. Advertise ahead of time – even if you have an opponent lined up, you want some looky-loos and if someone else wants to play you can always GM and facilitate.

All of these things are essentially signalling behaviour – this is a game that people want to play and there is someone actively trying to build a community.

Mugginns: know the rules back to front and know the period / battle / theater really well. Use at least tabletop quality painted minis and terrain. Bring as many handouts as you can – if units have statlines, make little cards for them. I suggest PowerPoint, it works really well for that. Have a bunch of quick reference sheets, possibly for players to take home with them. If you can get it, have a manufacturer send you some stuff to give away. Be enthusiastic – not over the top shouting or guffawing like you might see at a branded wargames store, but show interest and don’t use sarcasm a ton.

Ilor: It’s also important to have a plan. Know your terrain (how you’re going to handle pack in, setup, play, tear-down, and pack out), know the scenario and the forces backwards and forwards, and be prepared for all sorts of crazy questions. If you’re playing a particular historical action, know the history behind your scenario and be able to throw in a couple of cool details and anecdotes about what actually happened. That kind of immersion can go a long way towards firing peoples’ imaginations.

How do you get people interested?

Ilor: Gorgeous terrain. For real, nothing is as eye-catching as a board that looks and feels like a slice of a real life place. If you can put together a table that has really nice terrain on it, everyone who walks by the table is going to slow down to take a look, and that’s your chance to engage with them. This is especially true if you’re in a convention or games day setting and going to be running multiple sessions of your demo, as people who see the table early in the day will potentially sign up for later sessions.

Wowshawk: Advertise that you’re giving a demo as well. Just an A4 with the name of the system, and something like “learn to play system X in 15 mins” will help. Be friendly and outgoing, and invite people to play when they stop to look over your set up. I mentioned the clutter before, and you can elevate your space by simply using a black cloth draped over the table and some printed posters to make your demo table inviting. Practice basic hygiene and don’t dress like a pirate, even when giving out demo games of Blood and Plunder. A tasteful tricorne at the side is acceptable.

The thing about public demo games is that you’re probably representing your club or at least the game you’re playing. You don’t need a marketing degree to “sell” your game, but in my experience the stereotypical wargamer is a bit more shy and needs to be actively engaged. I’ve stood next to “demo games” where I had to ask to take part. Most wargamers tend to play with their club or friends, and have a nice network of people they know at cons, but that is a blind spot for new players and first timers. So breaking that habit is important. Networking is important by the way. Reach out to friendly clubs to showcase your game at a club night, most people are more than happy to find an excuse to start a new period or try out some new rules.

How do you set up a demo?

HardyRoach: In terms of running demos at your local club, rather than a full convention, posting your in-progress army pics of the club’s facebook/discord/whatsapp is always a good way to get people interested. Once they’ve shown interest you can jump on it and offer them a demo game. Also, you can just ask, “hey, anyone fancy a demo game of X?” Sometimes the most direct route is the best one.

Thundercloud: How do people contact each other and arrange games in your store/club? Facebook? Discord? Eldritch signs seen at dusk? Talk about it on there. You may get a couple of negative responses (because some people love being negative) but if you talk enthusiastically about something then the majority of people will tend to reflect that enthusiasm. If you are doing this at an LGS talk to the store manager, if it’s a product they stock they should be receptive, if it’s something they can order in ditto. If it’s a club thing share good articles or batreps (well done youtube batreps are not common but do exist).

Mugginns: I’d second Ilor’s take on terrain. Every single Warhammer player out there always says how great our terrain looks for historical tables. It’s easy, but not necessarily cheap, to get a bunch of pre-painted MDF stuff.

Also: don’t seat more than four players. People who have to wait will start looking at their phone and ignore you. If someone is clearly not having a good time you can suggest maybe they want to go peruse the stockist hall and seat a different player.

What scenarios do you use?

Ilor: In general I look for scenarios that are objectives based (as opposed to just “kill ‘em all and total up points at the end”), and especially those which force one side or the other to move. Static firefights sometimes happen in historical games, but those scenarios are a lot less interesting and engaging than those where someone is making a desperate push to seize an objective or hold out against a numerically superior foe.

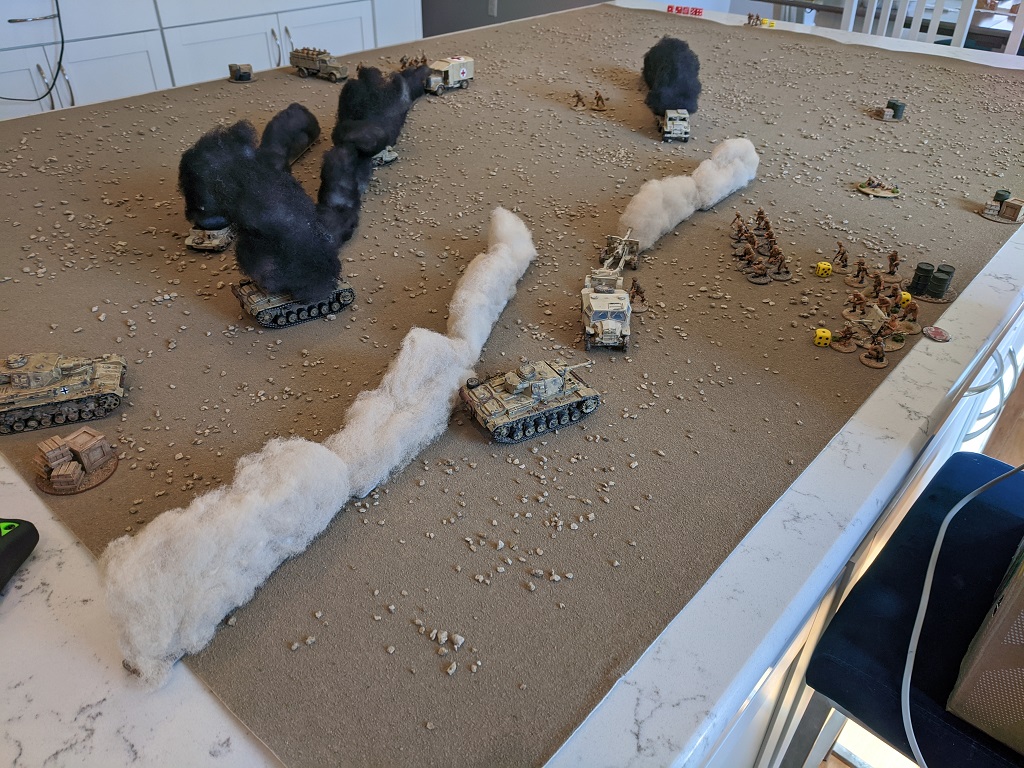

Thundercloud: This is another KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid) situation. An objective based game where you can’t sit in deployment zones and just shoot each other is best, and if there are dominating units that need a hard counter, then don’t bring them. 40k demos don’t get run with Warhound Titans, so don’t run your WW2 demo with King Tigers. Basic troops playing an objective game on terrain that pushes for movement and maneuver is the way to go in my opinion.

Mugginns: I’d second everything said above, and I’d also add in: something that is really theme-y, with maybe a theater you don’t see often. Marines fighting in a jungle versus Japanese SNLF is something you don’t see often and lets you explain some different forces to the players.

How do you present the rules?

Ilor: I’ll usually take a few minutes at the beginning of the scenario to explain the most basic elements (deployment, movement, firing, etc) and outline the objectives each side is trying to achieve. Then, over the first couple of player turns I will outline the different options or decisions available to each player as they are deciding what to do. This is where you can introduce special actions or troop characteristics that sit on top of the basic rules, something like, “Yes, you can have unit X fire at unit Y. But you could have unit X lay down suppressive fire instead, which would mean that unit Y will have a harder time hitting anything next time they fire. It won’t to any damage to unit Y, but it will help protect unit Z which you are trying to advance up the board to take the bridge.” Or, “Hey, if you want to throw a grenade or two prior to your assault, you can do that. Here’s how.”

It’s important to avoid overwhelming people with too many options too soon. Let them get their feet underneath them and slowly add concepts. I often find that after just a few turns, players get the hang of the basic mechanics and start asking good questions about their available options.

You also can’t underestimate the value of a good Quick Reference Sheet (QRS). Inquisitive players will often take a look at the QRS and see some a more advanced game element you haven’t mentioned and ask about it. “Hey, I see a thing on here about smoke. Can I use smoke to obscure this gap right here?” Just a little bit of that and you’re off to the races.

Wowshawk: 100% this. My experience giving out demo games is that in general, most people tend to be very conservative when playing a new system, especially if it’s their first brush with wargaming. If it’s a con game and most people don’t have the time to commit to a two hour demo, it’s a good idea to heavily edit the battlefield. Position units in a way they get stuck in quickly, set up obvious situations where something interesting will happen, or a special ability gets a chance to shine.

For me the outcome of a demo game should be that your opponent not only tastes the period, but also the flow and timing of the game. How will a typical battle play out, what are the driving mechanics of the game. If there’s an activation hook or a cool mechanic that drives the system that should shine. Think back to the first time you played the game and what got you hooked. Focus on that.

HardyRoach: Yeah, absolutely. Teach the core mechanics first, everything else is just gravy. As long as the person you’re teaching knows the mechanics that make up the core flow of the game, you can just tell them how many dice they need to roll when it comes up. If you’re teaching Chain of Command, you want to get the player familiar with the Command Dice system first.

Thundercloud: Aim for a teaching game for the system that you can run through in less than an hour, ideally less than 30 minutes. Time for 250 point games of Bolt Action. Time for The Battle of the River Plate. Time for 2 motor torpedo boats to fight over recovering a downed flight crew in a dinghy. Time for a couple of cowboys to try to catch a couple of rustlers. A couple of squadrons of tanks meet in a deserted village with some surrounding woods to seize a key crossroads.

You need to have flavour in it, and teach the basic mechanics, but don’t overwhelm yourself and a new player. Can you keep all the info you need for each side on a single sheet of paper? That’s a good rule of thumb, even if you turn that into unit cards.

Is it fun? Are player decisions meaningful? Would you voluntarily play this game if you could? You need to be answering yes to these questions.

Running demos is an interesting toe dip into designing scenarios, and teaching something helps you really understand it.

Mugginns: Nothing really to add here except in my opinion, don’t take out any rules you find too complicated. Just figure out how to explain them better. Players want the real game, the real experience, and those rules writers worked hard to make something they considered the full game.

Ilor: Oooh, that reminds me – sometimes it’s good to teach a rule or concept and let players try it, then once they have grasped the significance of it allow them to roll things back to the beginning and try it again. When I am doing demos of Chain of Command for new players, I’ll try to budget in enough time to run them through the Patrol Phase twice – everybody sort of fumbles through it their first time because it’s fairly abstract, but after you’ve seen it in action once all the way through to setting up Jump-Off Points you quickly “get it.” Rather than penalize new players (on either or both sides) for a bad Patrol Phase, I give them the option to run it again, as it’s pretty quick and it’s a really important part of what makes Chain of Command so unique.

Goonhammer’s Top Ten Tips for A Successful Demo

- Make sure you know the rules

- Have a nice table and painted minis

- Be friendly and outgoing

- Make sure all the info the player needs is ready – is there an A4 play aid?

- Plan your battle with objective based play

- Let the opponent win, without letting them know you’re letting them win, make it feel earned

- Don’t hesitate to have a learning turn where you show people how movement/shooting/etc works.

- Make sure the game has flavour – give both sides a unit or two that does something interesting, but doesn’t dominate the game. Leave players understanding that flavour, and wanting more.

- Make sure the game is fun, that player decisions are meaningful, and that it is engaging?

- Make unit cards so players don’t have to flip through books – PowerPoint works great for it

Thanks for reading our roundtable – check back next week for more exciting Historical content! And if you have any questions or feedback, drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.