As we continue with our first month of Goonhammer Historicals and our trip through the wars of Ancient Rome, Lupe reviews Infamy Infamy, the new Ancients ruleset from Too Fat Lardies.

Let’s get this out of the way: Infamy Infamy might be the best historical ruleset I’ve ever encountered. There is so much about this game that is good, and we’ll go over it, but if you’re just here already interested wanting a purchase recommendation: go buy it. That’s all you need to know.

That said, let’s dive into why this is so exceptional as a game.

Trouble in the provinces

Let’s talk about what the game is and isn’t, because that’s really important. This is a skirmish game, designed for 50-70 28mm miniatures as a baseline. But unlike a lot of games that try and hit this point, it really genuinely is a skirmish game – it’s not trying to invent some scaled down version of mass battles, it’s doing its own very specific thing. It doesn’t fall into the trap of pretending that a skirmish ruleset is going to replicate the large formations of famous battles.

TFL have really honed in on the asymmetric warfare that is described in many of the accounts of the time, and which is still familiar today – one of the touchstones I wasn’t necessarily expecting to find in my experience of this game was warfare in Vietnam or the Gulf Wars. The barbarian forces play much more like insurgents than any conventional forces, with the Romans suffering ambushes, uncertainty of enemy positions and other issues common to engaging irregular forces.

This really makes the game something unique, and anchors it really strongly to its time and place. If you’re keen to portray Roman civil wars or clashes between Gallic tribes, don’t worry however, these rules definitely allow for this and they’re interesting in their own ways. But do not go into this game thinking it’s a broad ancients ruleset you can easily use to play other periods and forces – the entire game has clearly been built from the ground up to do this very specific thing, and do it very well.

It’s hard to overstate how much this game really digs into this specific setting and type of warfare. Every major element we’ll look at here is in service to the goal of evoking it. This is both its greatest strength and weakness: it means that there is, to my mind, no game that so elegantly and faithfully covers its subject matter; but equally if that isn’t something you’re interested in, there really isn’t much here for you – instead try one of the mass battle systems. Luckily, the Lardies have done an excellent job of making this period and type of warfare engaging and intriguing, and I genuinely think a broad spectrum of gamers will enjoy these rules.

Civilisation and barbarism

The great tension underpinning this game is between the “civilised” Romans, with their best formations and comprehensive drill manual, and the “barbarian” enemies they face, whose fervour and unpredictability is a strength in of itself. It’s clear that this game was built from the very start to show off this dichotomy, and there are few rules that don’t reinforce this difference.

The first big difference is that the units themselves are different: not only do they have different stats and abilities, but they are different sizes. Uncivilised mobs run in groups of 10 models, while formed civilised troops present themselves in groups of 8. It’s a subtle difference, but when you have full forces on the table the Romans often feel outnumbered, even if there are the same number of groups in each force. Each faction (Republican Roman, Early Imperial Roman, Britons, Gauls and Germans) has a number of core lists and a bevy of support options, so these distinctions are well represented beyond group size.

But this all pales in comparison to the difference in how they operate. In short, the Romans rely upon their drill, and the barbarians on the commands of their leaders and their fervour.

Roman drill relies upon tight formations of troops and specific maneuvers and abilities that can be triggered at any time with signa cards (a command resource common to all factions) even interrupting enemy actions to do so. This makes them very reactive and flexible, within certain parameters. They can brace to receive a charge, or hurl pila to blunt it, raise shields to defend themselves against arrows, or reinforce the front ranks in tense melees. These drills are essential to the success of the Roman general – if used correctly, the force becomes a well-oiled machine, reactive and efficient. If not, then the lines will be bogged down and overwhelmed.

The Romans can also, unlike their foes, organise into formations and adopt close or open order. This lets them be much more flexible, with legionaries able to adopt marching formations to move quickly, open up their formation to give more room for sword swings on the attack, or close ranks to defend themselves more effectively against enemy charges. The Roman forces are a scalpel, and need to be wielded with finesse. Keeping track of the formation and order of your groups, and managing your resources and drill, is essential.

The barbarians have a very different experience. They lack the drill of their opponents, instead generating a resource called fervour. This makes them harder to break in combat, but also gives considerable bonuses to movement speed and the ferocity of their attack. It’s also a spendable resource, trading in ongoing benefits for more substantial ones immediately. Barbarian leaders can attempt to build fervour in their troops, and there are a few other ways to do so, and managing this resource is absolutely essential. There’s an interesting twist that if a leader accidentally generates too much fervour, the morale of the troops collapses, reducing it to close to nothing. This is the only game I’ve seen to represent that over-egging of a commander, the way in which not timing the execution of your action has consequences. It also gives the barbarians a kind of push your luck mechanic, as you try and find that fine line between maximum fervour and pushing things too far.

The barbarians don’t come together in organised formations, but instead clump together into mobs. These can be controlled or uncontrolled, but are looser and less predictable than their Roman counterparts. Controlled mobs are slower but keep together, while uncontrolled ones are faster, but run the risk of some groups falling behind or getting too far ahead, and their contact with the enemy being muted by the chaos of their lines.

Their leaders can also issue commands, but, and this is important, only on their own action. Whereas Roman drill can be used flexibly throughout play, barbarian commands are only used by leaders when they activate. They’re also more limited, allowing for simple manoeuvres like forming shield walls and gathering groups within a mob together on his position. They’re important and effective, but nothing like the elegant tactics of the Romans.

There are further distinctions between the barbarian factions and the two Roman varieties too.

The Republican Romans have access to slightly different drill, allowing their groups to rotate in and out of combat. They also have access to troops from across Roman territory, still fighting in their own national style, including Numidian and Iberian troops. These have their own special rules that make them distinct: the Iberians can fight in mixed cavalry and infantry units, while the Numidians throw javelins when they evade enemy charges. There are core lists reflecting allies from each of these regions allowing for some very interesting variation.

The Early Imperial Romans are a more homogeneous force, representing the transition to more uniform auxiliaries. This makes them the most organised and well-drilled force available, though they can be supplemented by a wider range of Roman troops from engineers to the cohores urbanae (who acted as a sort of police force in Roman cities), as well as tribal allies. This could let you represent all kinds of interesting lists if you wanted, from slave uprisings to rebellions.

The Britons get access to chariots and this is a huge deal. Chariots are presented authentically for the period, being used more as transport and as a command platform than as a weapon of war. Groups of warriors can pepper their enemies with javelins from them to build fervour, and use them as rally points to let them make hit and run attacks and reposition quickly.

The Gauls are probably the simplest of the barbarian factions, really honing in on the use of fervour. They can however take mercenaries from other areas, giving them limited access to some of their special skills, and the Belgae can recruit freely from the German lists.

The Germans are an extremely aggressive force, with cavalry and foot moving together freely, and their leaders being strongly encouraged to lead from the front. They also have access to Foederati, the German troops who were trained and equipped by the Romans, and who rebelled frequently. These are the closest the barbarians have to troops like the disciplined Romans, with access to a special maneuver to hurl javelins before contact with the enemy like the Roman pila.

Fog of war

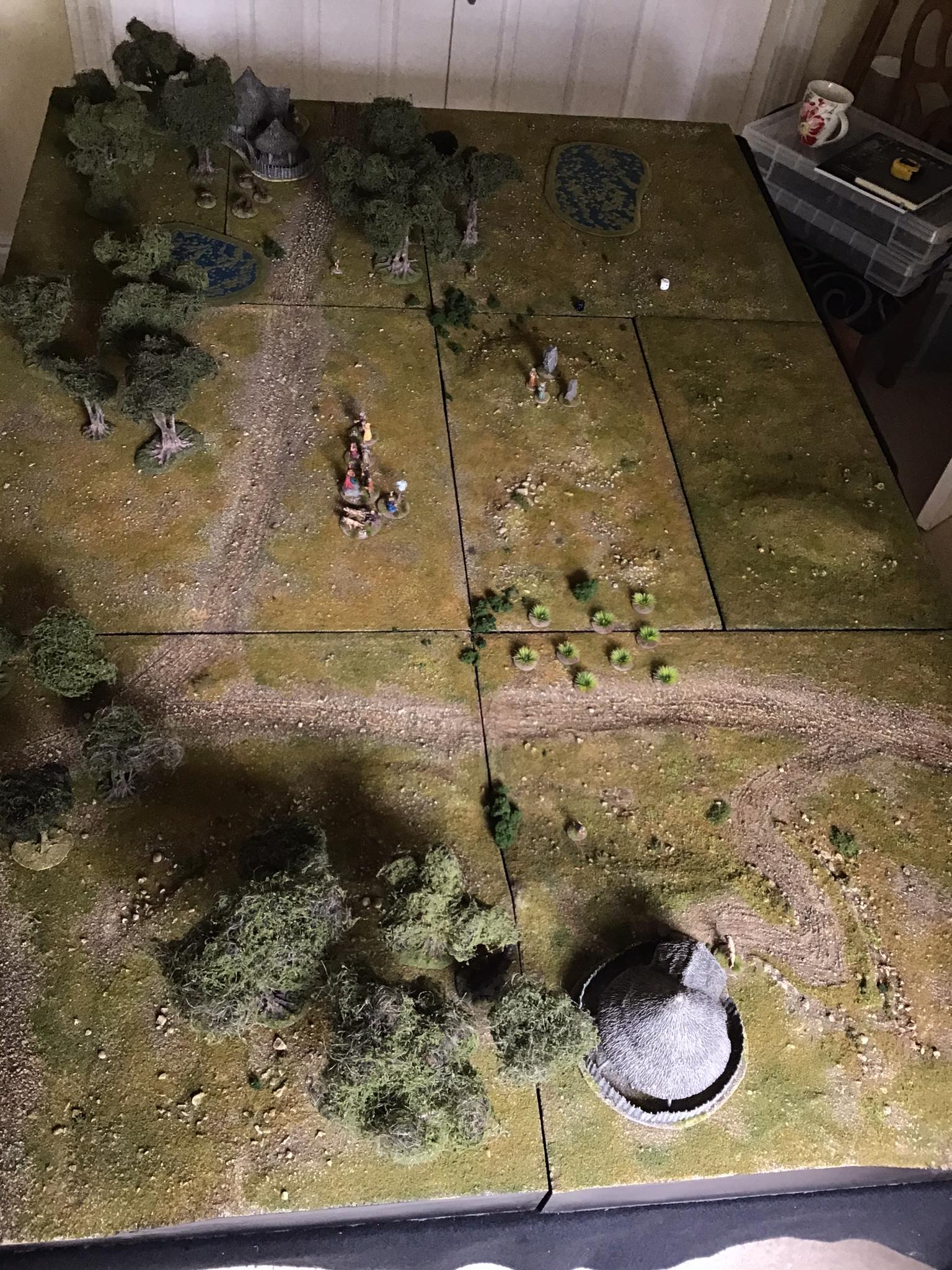

The drive to evoke this asymmetric warfare does not stop at the army selection step, but instead is reinforced repeatedly throughout board setup and play. The creation of the board is one of the most interesting parts of the game, and yet probably its biggest barrier to entry. Players need to know that it will be an enormous investment to get a board ready for Infamy Infamy, because the terrain requirements are intense. It makes perfect sense as you begin to play, but up front it can be extremely intimidating.

What the terrain looks like depends on where you’ll be playing. The Roman provinces are the most cultivated and least cluttered, while Germania is densely forested and Britannia is cluttered with hills and marshlands. Each region has a table, with random rolls determining how much of each type of terrain is generated, and where it’s placed. The upside to this is that it creates an authentic and suitable table to play on, tailored to the force that is home to it (barbarians consider fighting on home turf a support option worth points normally used to buy army options). The downside is of course that you’ll need a massive amount of terrain, and you won’t know exactly how much of each type before you start. I, personally, don’t own seven 12″ square areas of woodland which is how many you’ll need in half of your games in Germania. I’m not convinced my local club has that much forest terrain on hand.

There are ways round it – placing bases or templates representing forest, simply using all you have but no more, and so on. But these are unsatisfying, and the rules are clearly intended for this much terrain. I’ve been in a frenzy making scenery for my table since getting these rules and I’m slowly approaching enough… and I’m playing in 6mm. This is, in all honesty, the biggest misstep of the game. It makes total sense given everything else, and yet it’s a huge barrier to entry. One of the reasons that games like SAGA are great entry points is that they don’t need elaborate boards to play on. Infamy Infamy requires a full 6×4 table with more scenery than any other game not based around urban warfare that I’ve played.

That said it’s hard to argue with the results. The terrain really serves a purpose. In their own territory, barbarian forces use it as their major deployment mechanism. The scouting phase in these regions involves the barbarian player placing six ambush markers in terrain that’s not been scouted by the Romans (not within 12″ of the Roman deployment zone), and the Roman player placing one for each allied tribal group in areas they’ve scouted. That done, the Romans have a chance to try and scout the ambush markers the barbarians have placed with cavalry, if they have any, and the barbarians can screen these with their own cavalry. It becomes a shell game, as players secretly scout and screen markers, trying to ensure that deployment favours them the most. Scouting them can downgrade them to deployment markers, or even remove them entirely.

And it’s hard to overstate the impact that ambush markers can have. Barbarian (or light Roman) troops can deploy from ambush markers directly into contact with the enemy, smashing into their lines and causing immediate chaos. Ambushed Roman forces can’t react with drill, leaving them comparatively defenceless. Deployment points are also useful, but the barbarians placed by them can’t ambush their enemy directly, giving them a chance to respond. Drawing the enemy out is essential for the Roman, and waiting for the right moment to ambush and destroy their enemy the key of barbarian play.

In Roman territory things are less unpredictable, with ambush points being fewer in number, and only one at most will not be within friendly deployment zones. This dramatically changes the way the game unfolds, making it more a classic battle where units charge across the open field and smash into each other.

There’s no doubt the rules are set up for a Roman vs Barbarian clash, but civil war games are referred to and there’s nothing stopping you from doing them. There is some confusion for me about how this works with these rules – the scouting phase references “the Roman force” very explicitly. What happens when neither is the Roman force? The simplest answer seems to be to treat one as the invader, but some clearer guidance would have been appreciated here.

Regardless, these rules are an absolute breath of fresh air from the drawn battle lines of many ancients games. There’s no doubt that the fluid battlefields and deployments of forces will yield a huge benefit in terms of replayability and variety.

The blood and madness

When you get down to it, the actual resolution of the battle is comparatively simple. Models add dice to combats, or to shooting rolls. Movement is handled relatively simply, rolling dice to see the maximum distance that can be moved each action, depending on formation and terrain. This random movement distance might be a surprise to someone coming from other wargames, but it serves a real purpose when coupled with the many ways to gain extra actions, giving movement and positioning a distinct push your luck mechanic. The joy of this game is in some ways that the guts of it are so simple – it lets the additional material that provides the complexity and intrigue shine without interference.

As an example of this, let’s look at how mobs of barbarians work. In short, if more than one group of warriors is next to each other they can form a mob, and be directed together by a single order from a leader. However there are two choices for structuring this mob – a controlled or uncontrolled mob. Controlled mobs move slower, but stay together, keeping the groups adjacent so you can guarantee they hit combat at the same time and have maximum effect. Uncontrolled mobs are faster, but each group dices for movement separately, so they can end up drifting apart. They remain a mob unless a group gets way too far out, but it means that instead of charging as a single mass, they can make contact piecemeal, limiting their impact. Leaders can counteract this a little with the To Me! command, drawing groups together when they’ve drifted apart, but it’s a genuinely significant choice. Your handling of mobs, how much control you’ll retain, is a vital part of playing. All of this nuance hangs off of the simple movement mechanics, where groups dice for distance, but uses the core feature of that (its randomness) to create meaningful decisions.

The turn structure deserves a quick look over – like many TFL games it eschews you go I go or even a predictable alternating activation system for something less predictable. Each leader has a card that’s shuffled into a deck – when the card is drawn, that leader acts. Alongside these are signa cards, command resources that are shuffled into the deck as the initial allotment to players is spent, to randomly come out and aid them.

Finally there is a Tempus Fugit card that marks the end of the turn – this card can be drawn at any time, so turn lengths are variable. Once drawn players get a chance to activate any units that haven’t acted with signa cards if they wish, but in a limited fashion (no drill or commands to be used). It’s an elegant way of ensuring that players can get essential units moving, but also ensuring it remains unpredictable about what will happen when. The system works equally well with the handsome poker chips that come with the bundle deal, drawing them from a bag one at a time.

There are a handful of scenarios, with some interesting objectives. They vary a lot, and again seem to be focused on the Roman versus barbarian battle that is iconic, with some of them being potentially tricky or nonsensical for civil war match ups. There’s nothing here that’s irresolvable, and honestly the core of the game is sufficiently interesting and varied that even if you were to run the simplest of scenarios repeatedly (a simple raid with the objective of making the enemy withdraw) you’ll see a lot of different outcomes and experiences.

When Courage Fades

One of the key features of many TFL games is ensuring that battles are not a slog to extinction. The way in which Infamy Infamy handles this is with shock and force morale.

Shock applies to groups – it accrues on them as they suffer defeats in combat. Points of shock reduce movement speed towards the enemy (but not away), reduce combat effectiveness and generally hamper the group. When shock exceeds models remaining in a group, things get dicier, and hard limits on actions creep in. An unengaged group simply can’t end its turn closer to the enemy than it began. If in combat, it will involuntarily withdraw. More than double the number of models, and a unit will be broken, often fleeing the field in disorder. Obviously this means casualties are a real threat, as they lower the threshold for shock breaking a group, but they’re not the be all and end all.

There are ways to recover shock. Leaders can rally their troops, removing points of shock. Barbarians remove fervour as if it were shock before they start accruing shock, making them more resilient. If a group rallies enough it no longer has more shock than models it can get back in the fight. Cavalry suffer a little worse, needing to rally off all their shock, to represent calming their horses.

Shock can be devastating to a group, but the effects of shock can be devastating to the whole army. Force morale measures the willingness to fight of the force as a whole, and units being pushed back out of combat, or breaking or being wiped out, has a brutal toll. The loss of leaders is also a blow, with wounded leaders, or leaders routing or being slain, having a ruinous effect if a player is unlucky. As force morale collapses, the consequences are severe. Signa cards are removed from the game to represent the crumbling chain of command, and any surly allied forces are likely to take the opportunity to leave you to your fate. This is one of the great weaknesses of the Roman force, that depends more heavily on those cards and whose forces can be left exposed by tribal allies deserting.

When force morale reaches zero, a force is broken completely. The game ends with the remnants of the army fleeing the field or surrendering. In most games, this is how victory will be attained. Notably, though casualties worsen the effects of shock, they’re not essential to victory. An army can win the day without losing a single soul, if luck runs that way.

This system will be very familiar to players of other TFL games, as it’s almost identical to that used in other releases. However this has the strong advantage of being well honed and tested, and it is an excellent system in their other games too.

Infamy Infamy, How Do I Get Infamy?

You can grab a copy of the rules from the TFL website. There are plentiful ways of building up forces to play, and we explored a number of ranges and an Infamy Infamy-specific starter in our Getting Started article for the period. But what’s the cheapest way possible to get this game to table?

Here’s what you’ll need for the ultimate budget Infamy Infamy experience:

- PDF of the Infamy Infamy rules (£16)

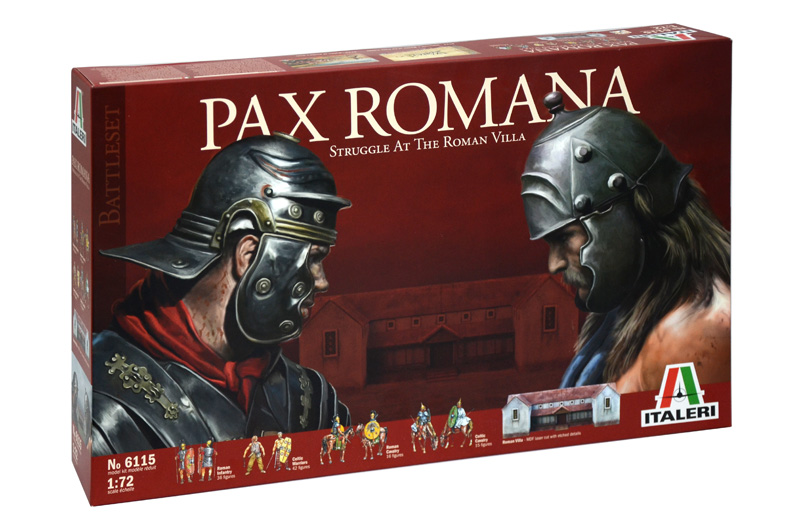

- Pax Romana set from Italeri (€57 direct)

- Some coloured paper to cut shapes out of

- Dice, counters, and the usual bits and pieces

Yeah that’s it. I found a copy of Pax Romana for £40 from a third party seller, so you can probably get started for under £60.

The minis you get in the Italeri box are 1/72 (20mm) bendy plastic like the ones your dad might have painted. They’re fine. Cheap and cheerful. You also get an MDF villa which is neat. Don’t bother with support options, they’re nice but… not necessary. Pick up another Italeri box if you want them (they’re dirt cheap). Cut out some shapes from the paper to represent your terrain. Get playing.

The forces insides don’t quite line up with anything in the book, so here are some custom forces to use them with:

Republican Romans

Centurion, Status III, Warlord

Two groups of 8 Legionaries

Optio, Status II

Two groups of 8 Legionary Recruits

Decurion, Status II

Two groups of 6 Roman Cavalry

Points Value: 114

Gauls

Leader, Status III, Warlord

Two groups of 6 noble cavalry

Leader, Status II

Two groups of 10 Ambaxtoi Noble Warriors

Leader, Status I

Two groups of 10 Warriors

Points Value: 106

Beautiful Chaos

With the chaos and uncertainty of the terrain, ambushes and deployment, force morale, turn structure and the uneven rhythm of signa cards, the game perfectly encapsulates the chaos of the battlefield. You don’t ever feel like you have no influence over events, but they do feel always on the edge of getting away from you. Events are uncertain, and you cannot guarantee when you will be able to act. Victory is in seizing the moment, and using your insights on the fly to achieve your goals.

Sid Meier defined a game as a series of interesting decisions, and by that metric Infamy Infamy is the most concentrated game I’ve ever encountered. Every element of it is packed with decisions big and small, and basically none of them are meaningless or uninteresting. It has its limitations, and there are areas I’d like to see clarified or expanded upon, but it has a clear vision and executes it magnificently. I’ve never seen a game encapsulate a setting or concept as effectively as this, and provide so much rich gaming experience in such an elegant package. The first few games may take a little getting used to, but I have zero doubt that I could teach this to people who had never played a wargame before with great success. And yet, I can think of few veterans who would not be enthralled by its depth and tactical complexity.

I would broadly recommend the big bundle as the counters and cards are very useful, but they are perfectly easy to replicate with your own materials

Pros:

- Innovative elegant gameplay

- Thorough evocation of the asymmetric warfare of the period and setting

- Simple to learn core mechanics with vast depth of tactical play

Cons:

- Lack of clarity around barbarian vs barbarian and Roman vs Roman games

- Extremely intensive terrain requirements

In summary, you should play this game. Even if you’ve never played historicals before, or don’t have a great interest in the period, you owe it to yourself. TFL have been making unique, interesting games for years, and all their skill has culminated in this.

![[40k] Competitive Innovations in 10th: Warping Time pt.2](https://d1w82usnq70pt2.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Analysis_Banner.png)