Welcome to Historical Roundtables, our regular column where the Goonhammer Historicals team gets together to talk over a particular aspect of historical wargaming. They’ll share their insights, recommendations and warnings about the best way to engage with the hobby. This week we’re going walk-trot-canter-gallop, hacking our way through wheat fields, getting an extra inch on roads and running up that hill with movement.

Previous Roundtables in this series:

Movement – important to the game, but mechanically a bit boring, right?

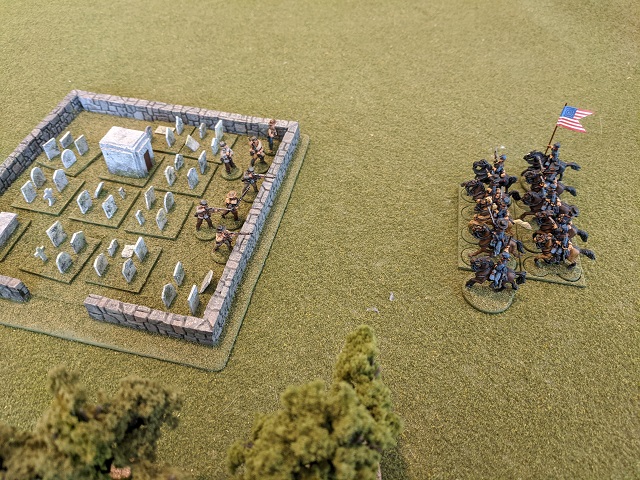

Ilor: Movement doesn’t have to be boring. I find that movement in TFL games like Chain of Command or Sharp Practice 2 are where a lot of the really important stuff happens – “can my unit get to cover before my opponent shoots it?” or “can I accept Shock/disorder from running if it means I get where I need to be this turn?” or even “do I think I can make this charge?”

And that doesn’t even get to those wargames where it’s not people moving but rather vehicles. The movement rules in Bag the Hun for instance are central to the game – if you can’t line up a shot against your opponent, you can’t fill their plane full of holes. Maneuverability for games about ships and planes can make a huge difference in how the game plays out. A well designed game is going to give the players important decisions to make about movement.

Mugginns: For sure there aren’t a ton of ways to actually do it, mechanically. There is the tried and true method that has been around forever in GW games where you move each guy using a ruler and make sure they’re within a certain distance of one another. There are some games that actually use more abstract methods – for instance moving from grid square to grid square, or cover piece to cover piece. There are systems like Bohica (Vietnam) where sometimes you don’t even have a force on the table to move around, you roll on a chart and maybe you put down a sniper or a squad to ambush the American forces in a guerrilla asymmetric fight.

Lenoon: I really like the idea of moving cover to cover – I can see something asymmetric, or where home ground advantage would really matter working fantastically well here. The Volgograd Tank Factory or French and Indian War spring to mind as interesting places for terrain-rooted movement.

Thundercloud: Ambush and jumping off points add a bit of variety, but these are more deployment rules. Similarly blips and concealed movement, which uses the same mechanics as standard movement but puts in a ‘fog of war’. Essentially the gaminess of wargames, where the player has more knowledge than a historical general ever would, means that movement with the knowledge of where the enemy are, what the enemy are is unrealistic, but we accept it because otherwise it would be really hard to even have a game.

What does good design in the movement phase look like?

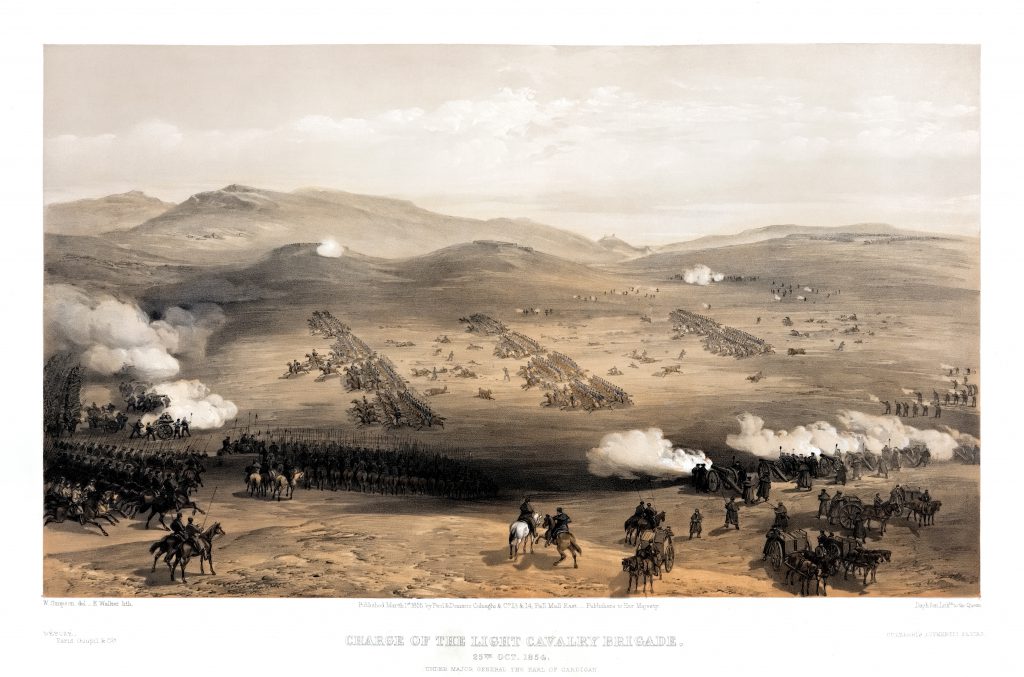

Lenoon: Even in a game or setting where movement is vital, the very essence of the period – like sweeping your artillery forward to blast opponents with grapeshot, or getting a really vital light cavalry move off to threaten a deployment point – I want movement to be easy to understand on the battlefield. There’s that idea that the best design is one where you don’t notice it, but you’re still influenced by it. I don’t want to have to stumble (ha ha) over movement rules when I’m trying to keep the overall strategic plan in my head. Good design is in mechanics that add a little friction or some choices without making the simplest mental calculations like “how long will it take my guys to get to the bridge” an exercise in frustrating calculus

Wowshawk: Should we talk about facing and pivoting as well?

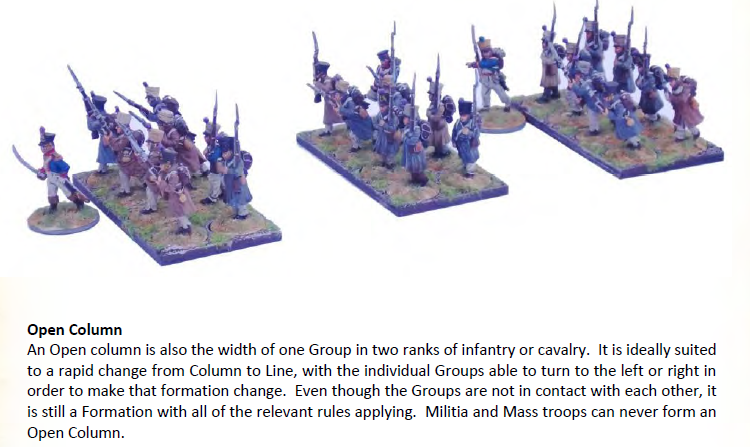

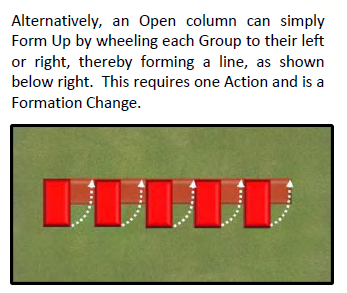

Lenoon: We should absolutely talk about pivoting! Pivoting and turning rules are a really good example of simple design being best, I think. Every game where facing matters needs a ruleset for changing formation, wheeling, pivoting, shuffling to the side and backward etc. Where it’s done simply and well for me is a ruleset that has a little give – it doesn’t matter if the final guy moves an inch or two further if the unit wheel takes ten seconds instead of minutes of geometry. You do need rules for it though, because otherwise facing doesn’t mean much if you can flip around from facing to facing! I like the approach to this in Soldiers of Napoleon. You can issue an order to wheel up to 90 degrees, rather than by X number of inches/cm, and you work that out by…… doing it. Having stands/set multibases really helps, but overall it’s no fuss, no muss.

Wowshawk: I like that you bring up shuffling to the side there, there are few rulesets that take this into account when doing Bad Things with a phalanx. But it was very much a thing (probably) so reflecting that is a real power move. It should feel realistic, without going overboard that it completely stops the game dead. Battlegroup has this different movement stat for on- and off road movement, which adds some interesting choices. Zippy wheeled recon vehicles can cover a good distance if they stay on the roads, but you’ll probably end up a smoking wreck if you stay out in the open.

I also want to add how you measure stuff out. The physical act of putting down a range ruler or measuring tool and implementing this in an elegant way. I think Zona Alfa is the only game I’ve played that has you put the model at the end of the distance moved, which is so simple yet takes away a whole lot of fidgeting when playing a skirmish game. Just plop down the ruler, lift, move, done. I usually use a gauge for this sort of thing, and it’s an improvement I have to say.

Mugginns: For units of minis (regiments, squads, whatever) I think facing definitely matters. When it comes to small warband sized games I am not sure I want to mess around with facing, mostly because of feels-bad moments where the opponent definitely believes you can’t see something but you can.

One of my absolute favorite things about Sharp Practice is that the authors included wheeling, moving from column to line and all the formations. I love that it’s basically straight from the drill manual. While you might not be using hundreds of minis you can imagine you are. I love it. Sharp Practice basically became my favorite minis game ever immediately when I saw it.

I do enjoy movement methods where you measure for each model, or in the case of units in formation, each unit. I like the accurateness of it and the tactile feel of moving around a battlefield. I also want rules for moving my leaders around – they’re the important guys. Whether they can attach to units or not, I want to imagine what they’re doing in a battle as well. I do appreciate games that give you choices or resources to spend to make your troops move faster or slower. You can run, but you might become disordered. Or you can run but you can’t shoot. Or the commander exhorts his men to step out and they go faster because they know the area well.

Ilor: I agree with Lenoon about simplicity, so long as the movement rules give the players choices. But just as important, in order for a game to have a well-designed movement phase, being in a certain place at a certain time in the game has to have some tangible benefit. What good does moving into a position to flank my opponent do if facing isn’t important and flank attacks have no benefit (throwing shade at you, Warhammer 40K)? Moving into range to attack or moving to an objective is the most basic facet of this, but good games provide more nuances to the effects of movement.

Lenoon: That’s a really good point. If you’re getting to the right place at the right time, it has to mean something – so games with flanking, positioning, facing – you know, actual rules about what units can do and see (definitely throwing shade at 40k), have to have clear, consistent and important rules about movement. You can’t get away with just saying “move them x”.

And the flip side – what’s the worst way to move?

Mugginns: I’m not very appreciative of units with huge movement values. I think it cheapens the game a bit – it becomes one turn of setup and one turn of charging or flanking, without all the maneuver that makes a wargame interesting.

Lenoon: I think there’s a place for massive movement values, but they have to be balanced against everything else. In Napoleonics you could give your scout cavalry a massive movement stat, but on the understanding that they’re not actually going to do anything to an infantry line when they get there – if something can really book it around the table, it shouldn’t be able to crash into and through the enemy when it does.

Ilor: The worst for me is fixed movement where facing doesn’t matter. Yawn.

Thundercloud: I’ve seen random movement distances where facing doesn’t matter. Why, why would you do that? Isn’t that just Ludo? They combined it with no casualty removal, so you just needed to keep breaking the enemy until they randomly retreat off the board.

What do you think about random movement?

Mugginns: At first when I played games with random movement I really didn’t like the idea. Once I’ve played a ton of it I like it. I’d put it on the same level as fixed movement values, to be honest. I like that it simulates not knowing exactly how well your troops will perform or take your orders – they might see an enemy force and go to ground, might stop to get through some brush, etc.

It adds an element of fog of war or friction, which is good for the game as well. Who knows what Lee could have done if Jeb!’s cavalry had rolled better on their movement around Gettysburg, or what would have happened if the German blitzkrieg through Russia hadn’t rolled so well?

Lenoon: I think games do well with a bit of random movement, but it depends on the command and activation systems. When you can guarantee your units will move, I don’t mind having random movement, but if you can’t guarantee your units will move then at most adding some randomness to movement (movement value +d6, etc) works but 100% random movement with random activation can bugger off. Double random – roll to see if they move, roll to see how far they move – is not ok. Stop doing it, games designers, please!

Wowshawk: That’s funny, I was just thinking that. The double whammy of a push your luck system with random movement would make a very static game and at that point you can push your agency out of the window. Faced with the choice, I’d rather have no movement due to fog of war then the limited movement (those cases where you just need an inch or two to make your maneuver work) because one of the people in your unit stepped on a hare or tripped over a mole hill.

Ilor: I love random movement, and I’m even OK with it in cases where you don’t have guaranteed activation for all of your units. Chain of Command has both, and the level of friction it brings to the table is just delicious. I often describe it as “barely managed chaos,” because it is. It also really captures the uncertainty and unpredictability of combat conditions. That said, Chain of Command offers the player some amount of choice in unit activations, so if you reallyreallyreally need to move a particular unit, you can often (but not always) mortgage the activations of one or more other units to get it done. I agree with Wowshawk that this would be much less enjoyable in a push-your-luck activation system.

But then again, I hate push-your-luck activation systems.

Wowshawk: I get that, it’s certainly not for anyone, and can be frustrating if you’ve got a lot of turn over due to bad dice.

Thundercloud: I think it can be done really well, because units moving historically were all over the place (even if they didn’t have a brilliant idea like looting the supply train and go and do that instead), but it doesn’t necessarily translate into good gameplay if units come up with their own cunning plan. That however factors into leadership and psychology, and then you are looking at what level of simulation you want. Knights who charge everything in sight because they’ve spent all this money on a big horse and armour and they want to get some use out of it is historically accurate, but not necessarily a fun game.

Let’s talk about hidden movement – what are your thoughts on it?

Ilor: I loves me some hidden movement (mainly because I loves me some ambushes and the arrival of troops from from an unexpected direction), but it’s really hard to model in a way that works without an umpire. Having units “under blinds” is the easiest way to do it because the blinds can use the same movement rules as everything else – simple – but honestly units under blinds really don’t do anything for me. Even if you allow for a certain number of “dummy” blinds, it still gives away a lot of information.

In some ways hidden movement is best handled as an alternate method of deployment, but I think there’s some utility to giving players the option to move their units around using a simple movement system. So maybe rather than moving a blind around, the player notes down a clock direction and distance each turn. Then, when it comes time to reveal the unit, you measure out the steps of the route and place the unit on the table.

Lenoon: I’d like to see how that would work in practice because I can’t help but think even the most honourable opponent would be tempted to just give a little….. Nudge in the right direction from time to time. Hidden movement for me works best with counters representing units, but then you’re just moving a (potentially big) chit or marker around, and you’re right that isn’t very satisfying. Having said that, if you’re playing something with a hex or grid it should be easy to do fairly without an umpire – and so many video games manage it, I’m sure there’s some megabrain out there with a system!

Mugginns: I don’t know about hidden movement, to be honest. If it’s chits or something, or fake tokens? Maybe I could get on it. But like I think I’d prefer the Sharp Practice way where you deploy from a point and it considers that as hidden movement – it’s abstracted. Your guys have been moving around behind trees or other obstructions and now they just came into view of the enemy.

Wowshawk: Ilor’s idea of mapping stuff out seems pretty good. That way you can account for deviations due to patrols or random stuff happening. It’s also good training for eyeballing distances on the tabletop! I’m definitely keen to try that out if I don’t have an umpire handy. It certainly seems handier than working with a map of the tabletop. Even then there’s the temptation of err, “modifying” a little bit, but I think that can’t be helped. The simplest way is to do the hidden movement before the game, and just map out appropriate positions, ambushes and booby traps on a map. That’s of course less dynamic and it’s hard to explain why an anti-tank team has to stay in their prepared position because they’re facing the wrong way when a tank comes trundling by.

Thundercloud: Hidden movement pretty much necessitates a GM. And then you can have movement hidden from both players as the concealed guys decide to go a different way and end up in different places. Yeah, why not go the whole hog and have movement concealed from both players. It would be interesting and simulationist.

Wowshawk: That sounds like it would rule, set up a plan according to a map and, if you’re lucky, local intel. Let an umpire plan out the moves till contact based on the actual conditions on the ground. You’d basically be the general telling a company to “take that hill!”

Taking Our Thoughts on a Flanking Maneuver

Ilor: OK, hear me out: we’ve talked about moving our miniatures, but what about also moving the terrain? Some historical games already have features that allow the players to add or remove or shift terrain prior to deployment, but what about moving terrain after deployment has already been completed?

For games whose historical context predates the 20th century, accurate maps were hard to come by. One of the reasons Stonewall Jackson’s “foot cavalry” made the Union army look like chumps in the Shenandoah Valley campaign was that he had a professional surveyor with accurate maps of the area on his staff. Early maps were more fiction than cartography, and the movement of terrain during the game might reflect the fact that your army has only the vaguest idea of how far it is to the village/ford/pass/whatever. I could very much see a system where until an enemy can draw actual line of sight to a piece of terrain, their opponent can move those terrain elements around – which could be super handy if they are objectives!

Rules like this could give a new purpose to fast scouting elements on the tabletop – fast scouting elements that are often passed over or left out entirely during list-building because they usually aren’t great in combat.

Just some food for thought to any budding game designers out there!

Have any questions or feedback? Have a great idea for a roundtable topic? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.