This week the Goonhammer Historicals team continues our focus on the Sharp Practice 2 ruleset, this time taking a look at the ins and outs of the firing mechanics.

So you’ve read mugginns’ last piece on the topic of movement and have carefully maneuvered your troops into position. Now it’s time to unload on your perfidious foe with a devastating volley of hot lead! This week, we’ll talk about how to do that in the context of Sharp Practice 2, which is designed to fight large skirmish actions during the Black Powder Era. And like the last article, I’ll be talking about this topic mainly from the perspective of the American Civil War, as that conflict saw the widespread use of major technological changes that ultimately lead to the end of the era: rifled muskets and cartridge-fed repeating rifles.

A Time of Technological Innovation

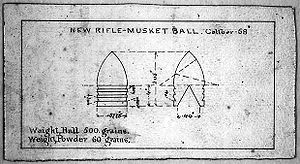

One of the things that revolutionized warfare during the American Civil War was the “Minié ball,” designed by French inventor Claude-Étienne Minié in 1848. Prior to this innovation, muskets used spherical shot. Fouling in the barrel caused by residue from the combustion of gunpowder after repeated shots often required these projectiles (usually encased in a thin fabric wadding) to be pounded down the barrel with a ramrod. In the case of rifled muskets, the lands and grooves of the rifling itself – combined with the tight fit required to engage the projectile and force it to spin – compounded this problem, making the rifled musket slow to load. In the context of Sharp Practice 2, smoothbore muskets require one Action to reload and rifled muskets using round shot require two Actions to reload. This reduction in overall rate of fire is somewhat made up by the increased range that rifles enjoy over smoothbore muskets.

In order to get around this problem of slow loading time for rifled firearms, Minié’s design used a projectile in the shape we now associate with bullets, which are generally cylindrical with a rounded conical front end. The real innovation of Minié’s new projectile, however, was that it had an iron plug in the base. When the weapon was fired, the iron plug would be pushed forward and deform the lead around it. This meant that the bullet could be made significantly smaller in diameter than the barrel, such that it would load more easily and be less obstructed by fouling. But the deformation of the back end of the bullet would form a seal which would tightly engage the rifling, increasing the combustion pressure behind the projectile. This in turn would provide both a higher muzzle velocity and spin that would stabilize the projectile in flight, which yielded better range and accuracy. In 1855, American inventor James Burton improved on the design, using a hollow cavity in the back of the bullet rather than an iron plug. This was not only more effective at forming a seal and engaging the back of the bullet to the rifling, but also resulted in a bullet that was cheaper and easier to manufacture.

The Sharp Practice ruleset accounts for this important period detail by allowing rifled muskets firing Minié balls to be reloaded with a single Action (just like smoothbore muskets), but with a range that is double that of smoothbore muskets to reflect the greater muzzle velocity and spin-stabilized projectile. However, because the Minié ball was a relatively new innovation at the time hostilities commenced, many units – especially state militia units – were still using older, smoothbore weapons. For battles set in this period using Sharp Practice, this means that especially in the early war you may have different units firing different types of weapons, with the troops armed with smoothbore muskets at a distinct disadvantage in terms of engagement range.

Here too there is a tradeoff, however, as smoothbore muskets could fire a combination known as “buck & ball.” This was simply a spherical musket ball and three or four pellets of buckshot loaded together as a single package, which essentially allows the weapon to act as both a musket and a shotgun simultaneously. This kind of fire was devastating at close range, and was a signature of the Union’s “Irish Brigade” for much of the war.

Firing Arcs

Once we know what weapons our troops will be using, the next major consideration is their organization, sometimes called their “order.” In Sharp Practice, there are three possible options here – in line order as a single Group, in line order as multiple Groups in a Formation, and in skirmish order. Let’s tackle these orders in order:

Single Group Line

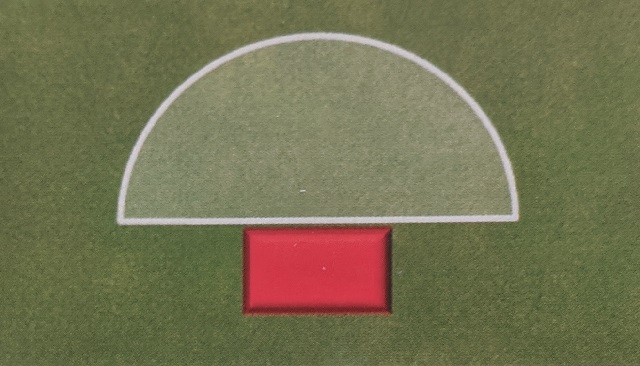

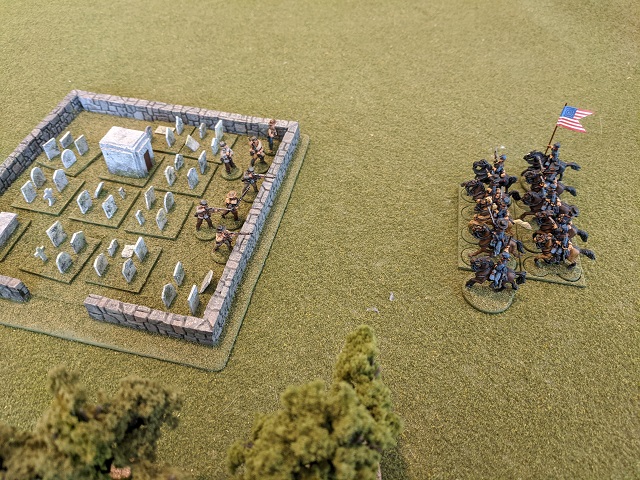

In Sharp Practice, a single Group of line infantry is 8 miniatures, usually organized in two ranks of four miniatures each. Single groups are very mobile, making them easy to move or change facing, and enhancing their field of fire. A single Group of line infantry has a 180-degree arc of fire to their front, meaning they may target any unit that lies at least partially in front of an imaginary line extending across the forward edge of their base.

Multi-Group Line Formation

Whereas units comprised of a single Group are nimble and have a good field of fire, combining multiple Groups into a Formation also has some advantages and disadvantages. The Formation is harder to move and requires a wheeling maneuver to change facing, but it allows fire that targets any constituent Group within it to be spread among multiple Groups. This makes the unit more resilient to the effects of casualties and Shock. The main drawback of Formations, however, is that they may only target their firing at units directly in front of them, i.e. to their front and between the two parallel lines extending forward from the sides of the Formation. This means that firing with Formations can be cumbersome, especially against nimble, fast-moving enemy units. Finally, only Formations may fire Controlled Volleys, but more on this later.

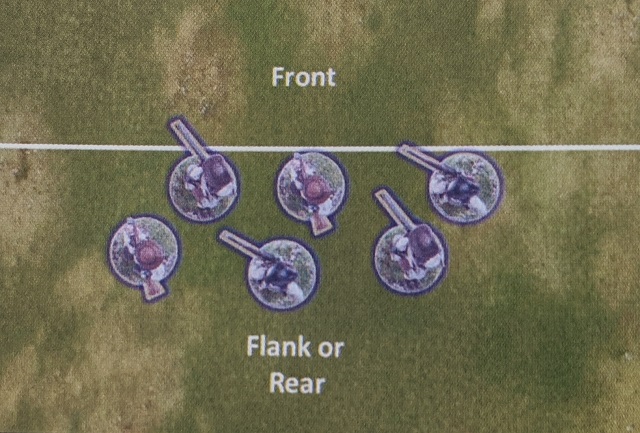

Skirmishers

Units in Skirmish order are not formed into tight ranks but rather into a much looser organization. In Sharp Practice 2, units in Skirmish order are comprised of 6 figures and organized in any shape so long as each is no more than 2 inches away from another. Generally, this tends to be loose, staggered lines. These units are treated as single Groups for the purposes of movement and firing (giving them a 180-degree arc to their front), and often get an extra movement Action to reflect their ability to quickly move over, around, and through terrain that would slow down more tightly-organized units. Skirmishers have an additional advantage in that they always count as being in one level of cover greater than what they actually occupy (e.g. skirmishers in the open count as being in light cover). Further, they may be used to screen troops behind them, offering those units a cover bonus as well. Their smaller size, however, makes them more susceptible to accumulated Shock, and being in open order makes them more vulnerable to close assault.

Firing Activations

Recall that each time a unit is activated it has two Actions that it may use. Last week, mugginns covered movement Actions, and here we’ll go into the three unit Actions that are involved with shooting – Load, Present, and Fire.

“Load” is exactly what it sounds like – after each shot, troops in the unit need to spend time reloading their weapons – tear open the paper cartridge, pour in the powder, place the musket ball or Minié projectile in the muzzle, ram it home, replace the ramrod, move the hammer to half-cock, place a new percussion cap under the hammer, and fully cock the weapon. Whew! As mentioned above, in the context of the game, all of these steps are undertaken together as a single “Load” Action.

The “Present” Action is everyone in the unit lifting and aiming their weapon simultaneously, but holding their fire until ordered. This is step is necessary and crucial in performing a “Controlled Volley,” which increases the unit’s chance of hitting the enemy. As a historical note, during the Crimean War it was recognized that having each man load and fire his weapon as fast as possible (as opposed to waiting to fire until ordered) actually increased the overall volume of fire put out by a unit, especially for troops who had less training in formal firing drill. By the American Civil War this was standard doctrine once firing had commenced. As a result, most ACW troop types have a “Controlled Volley” entry of “first only,” meaning that Formations may coordinate their first shot at the enemy, but after that it’s open season. Later Union units that had much better training are allowed to fire Controlled Volleys after their first fire, but these are the exception rather than the rule. Critically, Formations which are not firing Controlled Volleys are (as one might reasonably expect) firing uncontrolled. More on this in a bit.

Finally, there is the “Fire” Action, which is exactly what you might imagine. This is the part where you’re rolling dice and inflicting Shock and casualties on your enemy.

A Note on Action Order

Since units get two Actions when activating, if all your unit is concerned with is shooting at the enemy then it doesn’t matter whether your first Action is to Load and your second is to Fire or vice-versa – you’re still putting out the same number of shots per turn. But once the enemy starts to get into close range, you risk the possibility of being assaulted in close combat (or “fisticuffs” in the parlance of SP2). Receiving a charge unloaded is a significant penalty – a 33% reduction for most infantry units – so if your enemy is edging towards charge range, you may want to take steps to ensure that you are ending your activation with your weapons loaded as opposed to unloaded. Similarly, receiving a charge both loaded and presented confers a bonus, so even if you may no longer be able to fire a Controlled Volley, you might want to take an action to Present if you feel an assault is imminent!

Weight of Fire

So how many dice are we talking? This one is easy – one die for each man in the unit. Thus, a full-strength Group of 8 line infantry will roll 8 dice, whereas a single full-strength Group of skirmishers will roll 6 dice. A Formation of 3 Groups of line infantry would roll a whopping 24 dice! Casualties will reduce your weight of fire on a 1-for-1 basis, and each Group’s accumulated Shock will reduce your weight of fire on a 2-for-1 basis (rounded down). That is, if a single Group of line infantry has taken one casualty and is carrying three points of Shock, it is rolling 8 – 1 – (3/2 = 1) = 6 dice.

Note that I say “each Group’s accumulated Shock…” – this is an important and often overlooked distinction; if I have a Formation comprised of two Groups, each carrying 3 points of Shock, I only lose 3/2 = 1 die from each (a total of two dice), rather than 6/2 = 3 dice. Being able to spread out Shock among the Groups in a Formation can often mean less overall reduction in your weight of fire, one of the clear advantages of Formations over single Groups.

Of additional importance is the idea of a unit’s fire being directed by a Leader. If a Leader uses one of his Command Initiatives to activate a unit, and if one of that unit’s two available Actions is to Fire, then that Leader may add a number of dice equal to his Status to the firing. This distinction generally means that units activated by their Leaders during the turn are slightly more effective than those activated with Command Cards after the Tiffin Card has been drawn to end the turn.

Once you’ve determined the number of dice you’re rolling, the next thing that we must determine is our target number to hit. We start with the range category, meaning the distance between the firing unit and the target unit. Sharp Practice 2 exclusively uses six-sided dice, so the range categories break out as:

- Close Range: 4+

- Effective Range: 5+

- Long Range: 6+

And here let’s circle back to our different types of weapon: Smoothbore muskets count 0-12″ as Close range and 12″-24″ as Long range. Rifled muskets firing Minié balls treat 0-12″ as Close range, 12″-24″ as Effective range, and 24″-48″ as Long range. This is a pretty big advantage to rifled muskets, as they can engage from outside a smoothbore’s longest range, and in the 12″-24″ range band they are twice as likely to hit.

In addition to the base “to-hit” number, there are a handful of modifiers that can make it easier to hit:

First Fire: It is assumed that before a battle starts, the troops have been able to load their weapons under ideal conditions, before the smoke and noise and blood and chaos rattle their concentration (which might in turn cause them to spill a portion of their powder or rush the tamping process, leading to inconsistent firing performance). Thus, the first time a unit discharges its weapons at the enemy, they can claim this bonus.

Controlled Volley: If a Formation has taken an Action to Present before firing, their fire is simultaneous, increasing its overall effectiveness on the enemy.

Skirmishers firing at Effective or Long range: Troops in skirmish order firing at longer ranges have the time to take more careful aim, and may claim this bonus. Once the enemy gets into Close range, however, skirmish troops are usually thinking more about “skedaddling” to avoid getting charged, and thus get more twitchy.

Buck & Ball: Troops armed with smoothbore muskets and having the “Buck & Ball” characteristic on their unit roster may claim this bonus for all firing at Close range.

There are a few more similar modifiers (e.g. for artillery firing canister shot), but for our purposes and the troop types common in the ACW, these are the important ones. Each of these conditions adds a +1 to the die roll, and importantly, these modifiers are cumulative – thus a Formation making a first fire Controlled Volley with rifled muskets at Effective range hits on a 3+ on a D6. Similarly, a single Group that is first-firing using buck & ball at close range would hit on a 2+. The only hitch here is that regardless of the final modifiers, a die roll of 1 always misses and a die roll of 6 always hits.

The Effect of Fire

You’ve calculated your weight of fire and rolled your dice, tallying up the number of hits. Now what? Well, that depends on who is doing the firing and whom they are firing at!

In general, units are firing at units, so if a single Group fires at a Formation (say of 3 Groups), then the firing Group may allocate all of its hits to the Formation (and those hits will be spread between the constituent Groups of the Formation before rolling for effect). Thus, single Groups may target any single unit (be it another Group or a Formation) within their arc of fire. But when Formations are firing, well, that’s a whole lot of guys blazing away at whatever is in front of them. When a Formation fires, it targets every unit in its (more limited) arc of fire. The only exception is for units that are screened by another unit of line infantry (and thus outside their line of sight) and more than 4″ away from whatever unit is blocking them from view. The only way to prevent catching everything in your arc is for a Leader to spend a Command Initiative to direct the Formation’s fire to a single unit, but even in this case hits will spread to other units within 4″ of the target unit (as well as among the constituent Groups of any targeted Formation). Formation fire is messy and indiscriminate!

Once you’ve determined which units are being targeted, you divide up the hits between them as evenly as possible before rolling for effect. Any “odd” hits are allocated to individual Groups (even in a Formation) by the shooting player if the target is in the open, or by the target player if the target unit is in cover. This is distinction is important, because Leaders are always attached to a particular Group, even when that Group is in a Formation. Thus, if you generate 7 hits against a Formation of 3 Groups in the open, and if that Formation is commanded by a Leader attached to the leftmost Group, you’re going to divide up the hits 3-2-2 with the 3 hits going to the Group that contains the Leader (as this increases your chances of wounding or killing him). And this is where a Leader’s ability to concentrate the fire coming from his Formation on fewer targets becomes important, as spreading out your fire dilutes the overall effect.

I stated it above, but I’ll reiterate it here because it’s a critical part about all this that often gets missed by folks who are new to the ruleset, and that’s that this division of the hits between individual target Groups happens before rolling for effect. This is key.

Once the hits are divided, you begin rolling for effect for each individual Group that has been allocated hits. The effect of a hit is based on the level of cover that the target possesses. A die roll of 6 (and only 6) is a kill in all cases. Against targets in the open, each result of 3-5 adds a single point of Shock. Against a target in light cover, each result of 4-5 adds a single point of Shock, and against targets in hard cover each roll of 5 adds a single point of Shock. All other results are considered a miss. Thus, rolling 4 hits against a Group in light cover, netting 6,4,4,1 would inflict one kill and two points of Shock.

Leader Casualties

If a Group which has an attached Leader suffers any kills, then a roll needs to be made to determine whether the Leader is one of those casualties (and this is where the oft-used TFL catch-phrase “check your leader” comes from). This check is made using a single D6, and if the resulting roll is under the number of kills inflicted on that Group, then the Leader absorbs one of those kills. A subsequent roll indicates the effect, which might be either an outright kill, a reduction in Command Initiatives, or being knocked unconscious for a time. Because the roll must be under the number of casualties inflicted, your Leader is safe if the Group only suffers a single kill result. But crucially, skirmishers confer a -1 to this roll, meaning that they are more likely to inflict Leader casualties than regular troops firing en masse. But then again, using skirmishers to snipe out officers is a time-honored American tradition dating back to the French & Indian War!

Shock

Kills are bad, but in many ways Shock is worse. Shock represents the deteriorating morale of an individual Group (as opposed to Force Morale, which relates to your army as a whole). It is the combined effect of confusion, panic, exhaustion, minor wounds, and the steady erosion of command and control. As troops accumulate Shock, it impacts both their weight of fire and their ability to advance towards the enemy. Worse, once a Group has more Shock than men, it begins to waver and give ground every time it suffers further Shock. Each time a Group is forced to give ground in this way, it forces a “Bad Things Happen” roll, which has the potential to reduce your army’s overall Force Morale. Worse, if a Group that is part of a Formation is forced to involuntarily withdraw it has the potential to break the Formation, which is yet another “Bad Thing” that can happen.

Further, once a Group has twice as many Shock as men, it breaks and flees (yet another “Bad Thing”). And if that Group flees off the table and takes a Leader with it, that’s an even more dire category of “Bad Thing.” And once your Force Morale drops to zero, you lose! As a result, very rarely will you obliterate your opponent’s force during a game. Far more frequently, the effects of breaking units and Leaders getting wounded, killed, or routing off the table is sufficient to see your Force Morale collapse long before your force is wiped out. This is very realistic, as men are more likely to melt away to the rear rather than stubbornly fighting to the last. Shock is easy to accumulate and hard to get rid of, especially as your Leaders (who can only rally off Shock using their precious Command Initiatives) get wounded or killed.

Ultimately, Shock is what wins games.

Uncontrolled Fire

We talked previously about Formations using Controlled Fire (in the ACW usually only as part of their first volley), but what about uncontrolled fire? Uncontrolled fire represents troops simply loading and firing as fast as they can, not waiting for their comrades before blasting away. Uncontrolled fire is faster than Controlled Fire because it skips a step – you don’t need to Present, and therefore can fire 33% faster. But there’s a catch, which is that if you want the unit to do anything other than repeat the process of Load; Fire (or Fire; Load depending on which they did first on the turn they started shooting), then you need to make a test to bring them under control first. For elite troops this is relatively easy, requiring a 2+ on a D6 roll. But regulars are one step worse and by the time you get to “conscripts and volunteers” (which comprises most of the troops on both sides, especially in the early war) you need a 4+, meaning that 50% of the time, your Formation is going to ignore your orders and continue to blaze away at whatever happens to be in front of them – which might be your own troops! If you’re planning on using large Formations, you might want to invest some of your Support Points in buying a musician (drummer, bugler, etc), as that grants a +1 bonus to the control roll.

Note that it is only Formations which suffer from uncontrolled fire. Single Groups are small enough that is it assumed the Leader can make himself heard to the entire unit over the din of a handful of muskets. As such, single Groups never count as firing uncontrolled and thus never have to test to regain control.

Author’s note: though it’s not explicitly specified in the rules, our house rule is that if an uncontrolled Formation can be activated, that it must be activated if the unit’s Leader card is drawn or if there is a Command Card available to activate it after the Tiffin. This prevents the gaminess of a Leader card being pulled and the player simply declining to activate the uncontrolled Formation in order to prevent any potential friendly fire incidents. This puts some teeth into the concept of uncontrolled fire and further distinguishes better quality troops from lesser ones. End of aside.

Unit Characteristics

In addition to the basic mechanics of firing, each unit may have one or more characteristics that can contribute to the efficacy of its firing. Chief among these, and one possessed by most line infantry units is “Crashing Volley.” This characteristic is powered by the expenditure of Command Cards, and as such you’ll want to be careful how you use it (Command Cards are a precious resource for command and control of your force overall), but if your unit executes a Crashing Volley while making a “Fire” action, any Shock it inflicts on a target is doubled! This is going to be most devastating in situations where you’re generating lots of hits or shooting at troops in the open, and a well-timed Crashing Volley can be a game-changer.

Similarly, both Union and Confederate skirmishers will possess the “Sharp Practice” characteristic. Like Crashing Volley, this one costs Command Cards to use (though its cost is fixed at 2 Command Cards rather than depending on troop quality), and it allows a unit which is loaded to fire immediately (or which is unloaded to load immediately). Crucially, this doesn’t count as a unit activation, meaning that its clever use can see a unit fire twice in a single Turn. This makes skirmishers even more dangerous, especially to stragglers or lone Groups like artillery crews.

Other unit attributes are considered “always on” and do not need to be activated by Command Cards. The two that are the most relevant for infantry fire are “Good Shots” (which adds a single die to a Group’s weight of fire when shooting) and “Poor Shots” (which deducts a single shooting die from each Group with the characteristic). Though none of the “basic” unit rosters for the American Civil War listed in the rulebook have either of these two characteristics, they are worth considering for custom units or scenarios representing units like irregular Confederate “home guard” or similar (who are likely to be classed as “Poor Shots” as a result of both a lack of training and old, obsolete weapons). Conversely, a specialist unit like Berdan’s Sharpshooters would reasonably be classed as “Good Shots.”

Finally, a player may expend Command Cards to add dice to firing, with each Command Card spent adding a single d6 to the unit’s weight of fire. Note that this is not per Group, but rather in total. For the most part, that makes this a tactic of desperation, used only as a last resort or when you know you don’t have anything else on which you can reasonably spend Command Cards in a particular turn (a rarity to be sure).

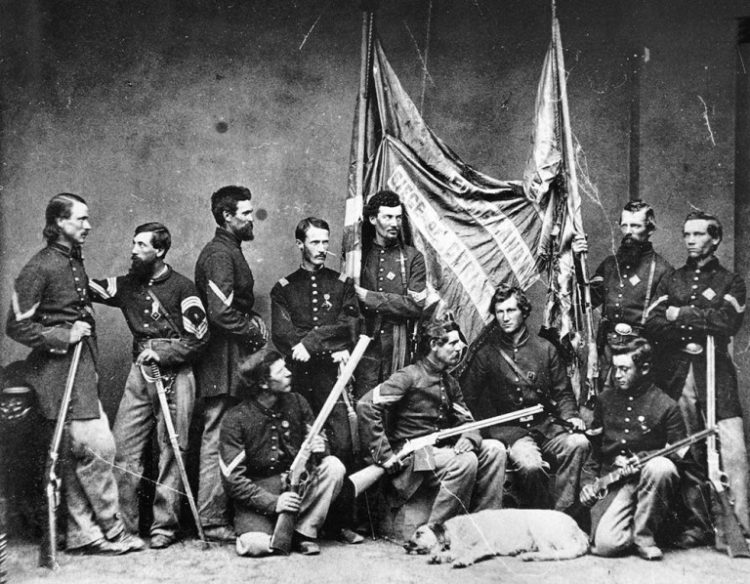

Breech Loaders & Repeating Rifles

I mentioned repeating rifles in the introduction, and this seems like a fitting topic to draw this article – and our focus on the American Civil War – to a close. The ACW is considered one of the last conflicts of the true “Black Powder” era, as it was one of the last that involved masses of troops using muzzle-loading weapons. By 1862, both the Spencer and Henry repeating rifles had started to enter service in the Union army. In particular the “mounted infantry” of Union Colonel John Wilder’s “Lightning Brigade” punched well above their weight when armed with such weapons. These firearms were cartridge fed, and used lever-action to reload. The Henry repeating rifle held sixteen shots and could be fired very quickly. After facing units armed with these weapons, notorious Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan quipped that it was a weapon the Yankees could “load on Sunday and fire all week.” He was clearly not a fan of being on the receiving end.

In the context of Sharp Practice, these weapons do not require an Action to Load, and can thus units armed with them may simply fire twice when activated. This is the definition of a “game changer,” because it makes units using these weapons extremely effective on the tabletop – just as they were on the battlefield historically. Even in the Union Army, however, they were still relatively uncommon by the war’s end, so they should probably be fielded sparingly.

Ultimately, between the advent of rifled muskets firing Minié balls and the invention of repeating rifles, the range, accuracy, and rate-of-fire made the concept of standing in lines and blazing away at each other even more suicidal than it had been for the previous 150 years. In many ways the technologies developed during the American Civil War were the bridge to modern warfare, as once these battlefield-proven “advances” were accepted by militaries around the world, armed conflict would never be the same.

We’ve spent quite a bit of time on the American Civil War – please catch up with us next week as we tackle a new topic, new war, or new game! If you have any suggestions for articles we’d love to hear them.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below, or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.