As recently discussed in our Roundtable article on gaming in the Medieval era, the age encompasses a large span, both temporally and physically. Because gaming systems and the models cover such a large period, it can be somewhat difficult to figure out how you should paint your miniatures. Luckily, there are a number of ways in which you can come to a conclusion to paint your dollies as you see fit.

The Historical Way (Lupe)

[Lupe’s Editing note: This was originally an effort post response to a question on our patron discord about how someone should paint their sergeants that Zuul picked up and ran with. Bear in mind this context, as that’s why I keep bringing it back to serjeantry.]

It all depends hugely on when and what the force is. Serjeanty, as in the professionalised social class of soldiery lower than knights, is a phenomenon that doesn’t last that long really, but what kind of thing they would wear would depend strongly on who is paying/organising the soldiers in question.

In northwestern Europe, during the 13th – 15th century, if they’re household troops (usually servants and attendants in the noble’s home who are called up for military service on top of their normal duties) would often be outfitted at least partially by the noble, especially if their lord were wealthy. Tabards, cloaks, jerkins, hats, etc., were common “uniforms” – though they absolutely weren’t uniform. These would generally be in their lord’s “colours” but they might also be in colours associated with a local saint or some other notable touchstone.

Beyond their household, the nobles would raise their troops via feudal obligation, and these would come in a variety of forms – lower ranked knights who would usually just attend themselves with their squires/servants, middle-class freemen (who would form the serjeanty at certain points in certain places) and peasant soldiers (though this practice died out slowly from the turn of the millennium to the point where peasant levies were rare except in times of extreme need by the 1300s – it also depended on locality, because the feudal obligation of peasants usually didn’t extend to campaigning – they’d fight if their lands were threatened, but not if their lord was going elsewhere, whereas the serjeanty would).

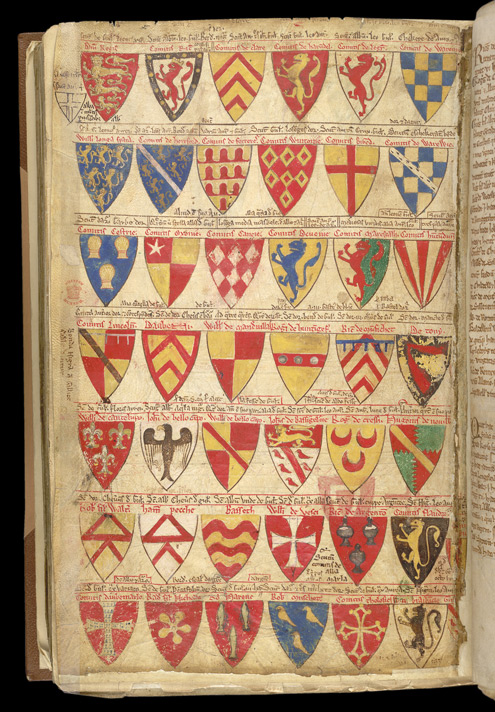

Knights would generally wear their own colours, or the colours of their lord cut with their own colours, or sometimes cut with the colours of someone else or something else. Serjeantry usually just turned up in their own clothes, though you might wear the colours of your town or city if it was notable and had some level of independence. You also had city militias and units that were raised by townsfolks, and who were provided by the town/city rather than a lord, but this was uncommon outside of the Holy Roman Empire. In terms of what colours they would have worn, I have this colour reference I use, which is a decent guide to what colours would be commonly available for ordinary people between about 800 and 1400.

Blacks and whites were elite colours and rarely worn by anyone not a noble or in the church, but undyed linen was also pretty common for everyone.

This began to change as sumptuary laws became more common, and by the 1400s undyed linen, blacks, whites, and browns were broadly the most acceptable colours.

The Historical Way, continued (Zuul)

If you’re more of a visual learner, one of the easiest ways to figure out how you should paint your miniatures is to look to historical paintings for inspiration. We live in an age where much artwork has been printed or digitized, which is good for visual references. For digital collections, medievalart.org has a nice collection of handy links that contain tons of visual references. In addition to these, major museums also have some of their collections already digitized that aren’t always on view, which is handy for folks that either live too far to visit or can’t. The main example would probably be Princeton’s The Index of Medieval Art, which is the largest archive of medieval art in the world. Currently, a subscription is needed to access the database, but that will be ending as of July 1, 2023, when it will be accessible without subscriptions. Bookmark this database for future use! Another source would be The Getty Museum – The Getty is a pretty big institution that is spearheading digitization efforts and many of its items are already digitized and free to access.

For print, there are far too many options to post here. Just go to your favorite bookseller and search for Medieval Art and tons of resources will pop up.

The Apocryphal Way (Zuul)

History has a way of working its way into our collective memories, especially through TV and film. This was touched on briefly in our Medieval Roundup, but it should be noted that you don’t have to be completely accurate when painting your models. It’s completely up to you, and whatever method you decide on should reflect your preferred painting style. There are plenty of shows & movies that you can look to for inspiration, like The Last Kingdom, Knightfall, Kingdom of Heaven, Medieval, The Northman, and Ironclad. Like all historical wargaming, they’re your miniatures and you should paint them as you see fit. As evidenced by this article, there is plenty of room to make your armies as riotous in color as you see fit. Or not.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.