Summer 2024 marks the 110th anniversary of the cataclysmic events that led to World War I. Despite being one of the most pivotal events of the 20th century, WWI has not achieved nearly as much representation on the tabletop as its sequel, and we at Goonhammer hope to shine a little light on this fascinating period of history. Therefore, Goonhammer is pleased to present our Guns of August summer event. Every Monday, from June to August, will see a new article on wargaming the Great War. Expect painting guides, model reviews, interviews, ruleset spotlights, and more!

In this article, we take a look at yet another upcoming ruleset for playing out battles in the Great War (it truly is a renaissance of WW1 gaming at the moment). This ruleset is called 1918 and is a late-war set of rules for playing out platoon-to-company sized battles on the Western Front. Today we’re joined by James & Sam, co-authors of the rules to tell us more about the rules!

1918 Ruleset Author Interview

Goonhammer: Tell us a little about the genesis of 1918 as a rule system. What compelled you to embark on the long and difficult journey of writing a new ruleset from scratch?

James: 1918 began a long time ago, back when I really should have been working on my dissertation on recruitment and patriotism in the First World War. The Great War has always been a favourite period of mine, and I had bought quite a few miniatures. The game began just as a means for me to craft rules for those miniatures and throw some dice. From its genesis I wanted to focus on the last year of the war, 1918, as I felt the battles in 1918 were more dynamic and showed more fully the breadth of the lessons and new technologies the combatants had developed from years of hard fighting. I wanted to go beyond the popular conception of the war and make a game that put players in the mindset of a contemporary junior commander, one still finding their feet in a newly developing era of industrial warfare. How players could navigate that fascinated me. The core rules took shape, but they have since grown and evolved in many ways.

A few years later, Sam joined the project as co-developer, providing a wealth of knowledge and energy that has really gone far beyond what I originally planned. The game is now much larger in scope and content. We both wanted a game that would provide fun, tense action with enough gaming ‘crunch’ and the right historical ‘feel’. What we are doing now far exceeds the original conception I had for 1918.

GH: With so many eras and theaters of World War I, why did you choose the Western Front in 1918 as the setting for your ruleset?

James: 1918 is a very under-appreciated year of the war. Popular history tends to focus on the Somme, Verdun and Passchendaele, which are interesting and important in their own right, but as wargamers, 1918 arguably has so much more to offer, and has been underserved.

In 1918 both sides were reaping the rewards of the technological, tactical and strategic innovations from the earlier years of the conflict, and systematically applying those learnings to how they fought. As a result, the combat in 1918 feels very much the prototype for the Blitzkrieg of the Second World War. Combined arms – between infantry, artillery, tanks, aircraft and cavalry – and movement, are key, which makes for a fascinating set of puzzles to give players to solve on the tabletop, as well as colourful and varied armies to collect and paint. Both from a hobby perspective and a gaming perspective, the First World War has so much more to offer than just drab armies of khaki running across a muddy field.

Sam: In terms of why the Western Front, the combat there in 1918 was amongst the most intense combat the world has ever seen. Only the Normandy campaign and battle for Berlin in 1945 really come close to the concentration of men, machines and destruction in such a small space. The conditions on the Western Front forced huge change in the armies and, contrary to the views of the Easterners of the time, the war was very much decided in the West. The German spring offensives, and the Allied hundred days offensives that followed, create a hugely dramatic, varied and dynamic backdrop for a wargame. The spring offensives were the last chance saloon for the Central Powers so the stakes couldn’t be higher (and they had a pretty decent shot in March 1918 at turning things around).

James: That said, there are hugely interesting, and very different, forms of combat going on on other fronts in 1918 – deserts, mountains, underground fortresses, civil wars and revolutions – and these are all things we plan to get to in time. All things going well, the Western Front is just the jumping off point to a huge and fascinating world.

GH: When you set about writing this ruleset, what were the objectives you hoped 1918 would achieve, in terms of a set of wargaming rules?

Sam: The most important objective for 1918 is that players have fun playing it! That said, 1918 is not really a ‘beer and pretzels’ style game. 1918 aims to be fun, but also historically plausible and ‘easy to learn, hard to master’. 1918 does this in two ways; firstly, by giving players interesting choices to make, but putting constraints, inspired by history, in place which force the players to make hard decisions; and secondly, at a more visceral level, by aiming to give players an experience that captures something of the ‘feel’ of the First World War.

Well, as much as pushing toy soldiers around can feel like war anyway (!)

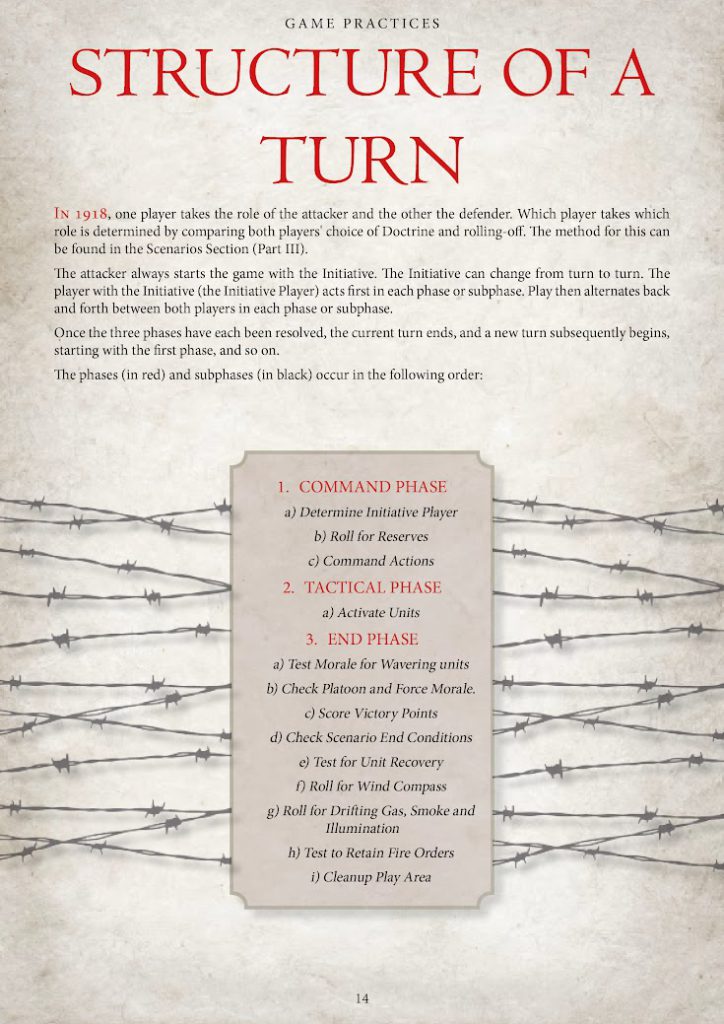

So how does the game set about doing this? Well, firstly, command friction is really important in 1918 – not everything will happen how and when you want it to. The game uses an order and reaction system (and alternating activations) that offset the omniscient position of the player and mean not everything will go according to plan and you’ll need to think on your feet.

Secondly, the game uses pinning and morale mechanics that represent the limits of human psychology in the age of industrial warfare. This means that often firepower is more about suppression, enabling movement, than simply piling up a bodycount. This leads to much more tactically interesting (and realistic) decisions to make.

Thirdly, leadership plays a central role in the game. Officers and NCOs have vital functions, not only in issuing orders, but also in rallying off pins, keeping your men in the fight, and generally improving the efficiency of nearby units. Sometimes, like in real historical accounts, the only way to keep your men going forwards under fire will be if an officer or senior NCO is personally leading them forwards and sharing the risk with their men.

GH: Writing a wargaming rulebook is a ton of work, involving endless research, brainstorming, playtesting, and editing. What have you found to be the most challenging part of the process? Which part has been the most fun?

James: In many ways the most challenging part was not what we expected – force selection. Of all aspects of the rules, this has gone through the most iterations and been the subject of the most discussion and experimentation (although some other bits, like artillery and pinning, have also had a fair bit of evolution).

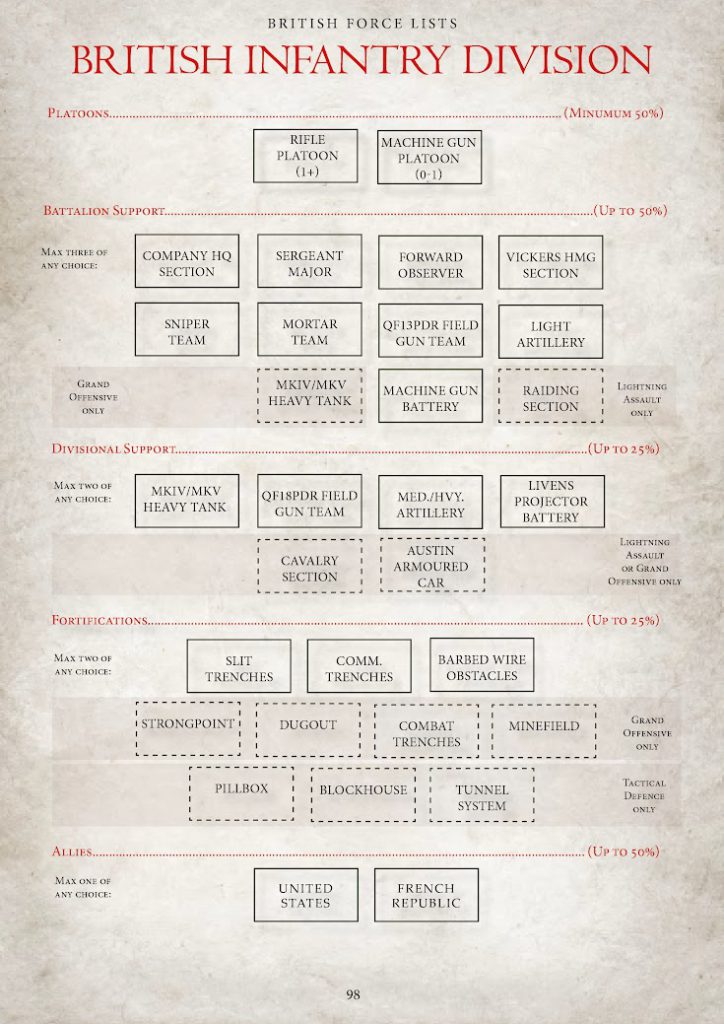

Sam: Partly, this is because we made a rod for our own backs as we decided that we wanted force selection to achieve quite a few things: 1) to provide real choice to support player agency, and replayability 2) to represent the breadth and colour of the armies of 1918 3) to be as historical as possible, and avoid lazy genericism, and 4) to provide, as far as is possible, a balanced game that both players can enjoy.

James: We’re proud of what we’ve created with the Doctrine and Force List system to meet this self-imposed brief, and can’t wait to see what the beta playtesters think!

Sam: For me, the most fun part of the process has been the opportunity to delve deeply and greedily into the history of the Great War, and to have the excuse to buy lots of books and watch/listen to lots of media on the subject! (“Honestly, dear, I’m working right now”). The Second World War is rightly lauded as an area where there is always more to learn, but I think that the First World War should also be recognised as a conflict with just as much colour, drama and depth. That said, it can be trickier to find good sources and media on the Great War as compared to its younger cousin. However, once you start looking, the seams go deep and rich.

James: In many ways, research is both the best and worst part of developing a wargaming system. How far we want to go as developers is married to the flexibility we want players to have when crafting their army, but also just how limited some sources are. Some of the armies of the nations involved are very difficult to research, and yet we want to make sure that nothing feels haphazard or undervalued. So we have made an effort to give players flexibility whilst keeping the structure and limitations as historically accurate as we reasonably can. We have also tried to include some really interesting platoons and forces, each of which present a unique challenges for players, so that the armies people play are quite distinct and exciting on the tabletop.

GH: Having browsed a preview of 1918, it looks like a lot of effort has gone into providing a historically accurate experience, with unit diagrams, histories, etc. How important is historical authenticity to you when it comes to wargaming?

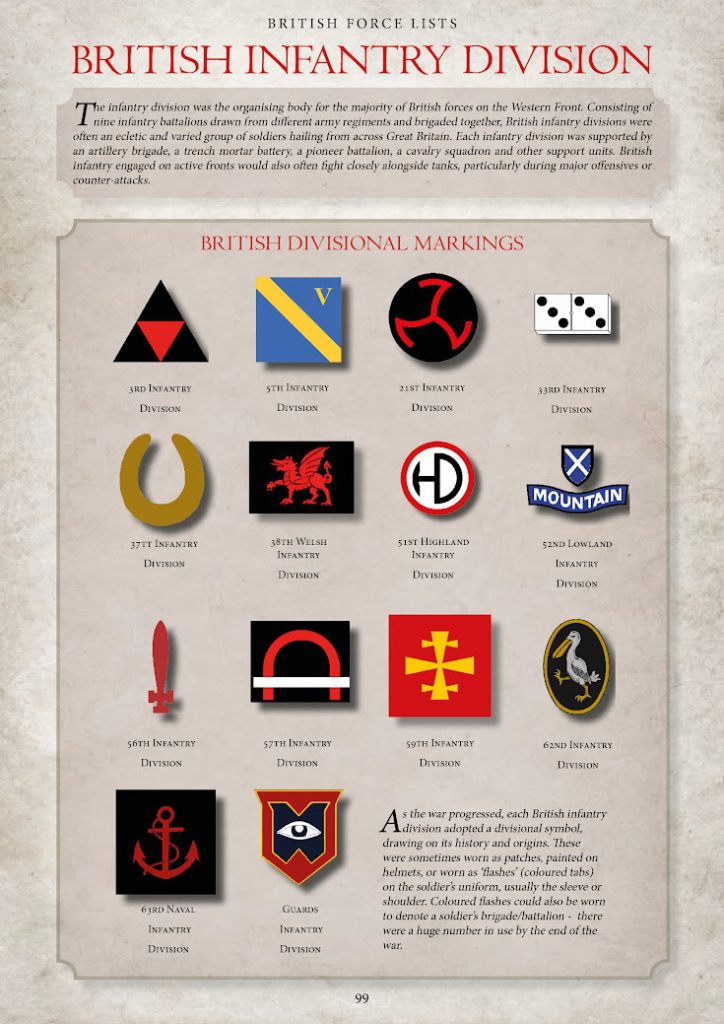

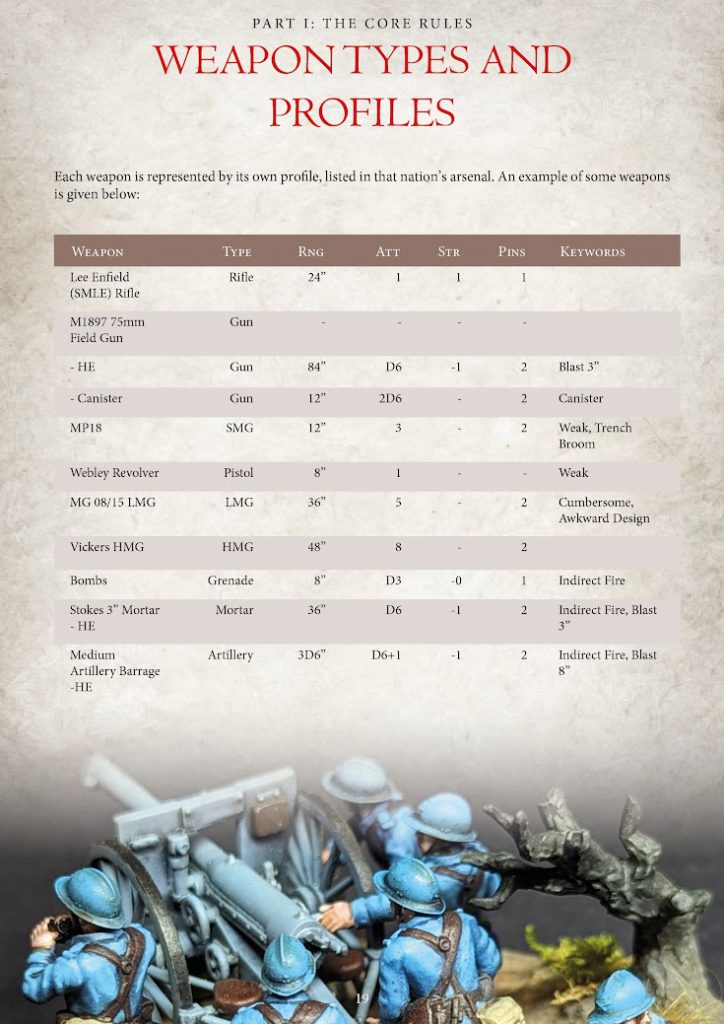

Sam: We’ve generally taken the approach that historical accuracy provides more opportunities than it does problems for wargaming. For example, when developing the force lists for the game, rather than pushing armies towards a ‘generic’ one-size-fits-all platoon or section structure, we’ve instead leant into the variety offered by the real historical platoon and section structures used by the armies at the end of the war. We’ve done something similar with the weapons. New weapons, like the light machine gun (first widely deployed by the French in 1916), had not yet been perfected. As a consequence, the performance and tactical uses of a French Chauchat, German MG08/15, British Lewis Gun and US BAR were quite different, and in a game where the section and platoon are the tactical building blocks, we think it makes good sense, both historically and in terms of gameplay, to represent this.

James: You mentioned the platoon diagrams – we’re very proud of these. We felt like many existing rulesets either ignored this aspect or expected the player to do too much reading or research to represent this in their games. So now you can have your cake and eat it; we’ve done the historical heavy-lifting so you don’t have to!

GH: WW1 is renowned, among other things, for trenches and mass amounts of artillery fire. How have you handled these aspects in your ruleset?

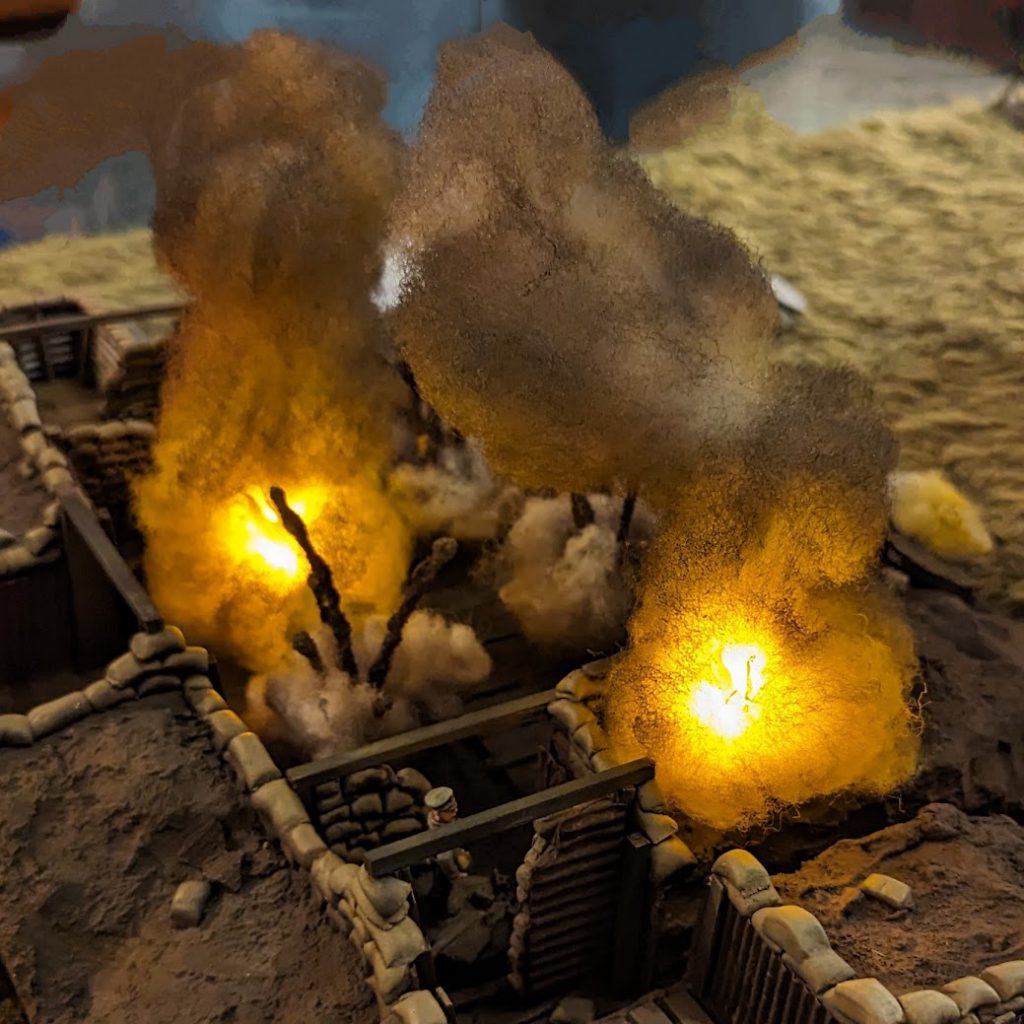

James: The first thing to say about trenches in 1918 is that you don’t need them if you don’t want them! The book will contain a good selection of scenarios which don’t use any trenches. This is because the battles of 1918 often progressed very quickly beyond the main fortification lines and in many cases into areas largely untouched by the war. That said, there are also scenarios which certainly do use trenches (sometimes in multiple lines) and these offer a completely different and fascinating set of tactical challenges for players (and fantastic opportunities for terrain-makers).

Sam: It’s also worth saying that by this point in the war, trenchlines were rarely continuous and there was a move to defense in depth using pillboxes and redoubts with all-round defense – so you won’t need yards and yards of trenches. Close quarters trench fighting is also very much a thing – and yes, you can get nasty toys like trench clubs, trench armour, flamethrowers and gas to clear the enemy out of their lines, traverse by traverse.

James: The key thing about the last year of the war, is that it was the last year of the war. Both sides had by this point worked out very effectively how to break into and through fortifications, and we give players those same tools in the game. Nonetheless, trenches are no joke – they provide significant protection for occupying troops, bonuses when recovering pins, and the ability to move around while staying protected.

Sam: Players can also add trenches and other fortifications, such as barbed wire and pillboxes, to their armies during force selection. So if you want to, you can lean into this aspect of the game when building your force by using the Tactical Defence Doctrine.

James: Modern artillery is a difficult subject for a platoon/company sized wargame. The sheer dumb-founding destructive potential of the artillery of the Great War can translate poorly to a platoon/company level wargame. Most games of 1918 are emulating just a small slice of a wider, massive engagement. Therefore, while players can access the heavy batteries that would be covering the whole crux of the offensive, they can’t bring all of that firepower to bear on their small slice of the battlespace.

Sam: Yes, so to get round this artillery problem, the game breaks artillery up into three chunks. Firstly, a couple of scenarios include pre-game preparatory bombardments as scenario rules. For this purpose, we assume that the defender’s force are the ‘survivors’ of the preparatory bombardment; they will suffer some pins (diced for just before the game begins), representing the dislocation of the bombardment and ‘race to the parapet’, but no casualties.

Secondly, players can take light/short-ranged artillery, such as infantry guns, mortars and anti-tank guns, in their forces. These are represented on the table with models and can be issued orders, suffer casualties etc like other units. They provide some advantages in attacking ‘clumps’ of enemies, tanks, and fortifications (as you’d expect).

Lastly, as part of the advanced rules, players can purchase artillery batteries during force selection. These represent the ‘big guns’ far behind the lines and are not represented on the table with models. The game assumes you’re not the only call on a battery’s time and ammunition, so you only get one barrage from each battery and it might not arrive on time. (You can take more than one battery in your force – but they cost points and force slots, so there are those hard choices again…) You can improve the accuracy and timeliness of your batteries with a forward observer, and there are also some choices about how you assign your batteries, with options like timetabled barrages, creeping barrages and observed barrages.

James: It’s also worth mentioning that apart from standard HE (high explosive) artillery can fire ‘special ammunition’, such as AP (armour piercing), gas, smoke, illumination or shrapnel shells, all of which have their time and place. The overall effect is that you can certainly inflict casualties with artillery, particularly on enemies foolish enough to stand in the open, but generally artillery is used for inflicting heavy suppression, either to disrupt an attacker or suppress a defender. With artillery, we have attempted to tread a careful line between playability, complexity and lethality, while giving the artillery of the Great War its rightful place as king of the battlefield.

GH: Your ruleset is designed to support battles from platoon up to company size. Can you tell us a little bit about how the experience changes from a platoon-sizes game to a larger company-sized one?

Sam: The standard game size is calibrated at a reinforced platoon – so around 40-60 models in total, including a basic infantry platoon, some support weapons, specialist infantry or cavalry (such as pioneers or trench raiders), on and off-table artillery, and a few vehicles or aircraft. We have found this takes around 3-4 hours to set-up and play to conclusion.

James: However, the rules can go much larger, with multiple platoons of infantry (aka a company), and in our plans for future supplements, whole sections of tanks and platoons of cavalry. These larger games lend themselves well to multiple players, with each player taking command of a platoon and its supporting assets, but you can expect to have to set aside an entire afternoon, or perhaps even a day for a truly huge game.

Sam: At this level of play, coordination between players becomes important (adding an additional ‘fog of war’), as does prioritization of Command Cards, reserves and activations across the battlespace.

GH: When I interviewed Alex Sotheran, we got to talking about misconceptions about WW1 that bothered us, from the idea that going over the top meant nothing more than being mowed down by machine guns, to the idea that the generals were all hapless buffoons. I’m guessing that you have some particular bugbears of your own – so what misconceptions about WW1 are most bothersome to you?

Sam: You’re right – there are loads! Perhaps the biggest for me is the way that the First World War is remembered. Unlike the Second World War, it’s often portrayed as a dull, grey, amorphous place where the only thing that cuts through to a modern audience is the senseless loss of life. This does a hugely vibrant and colourful period of change and high-stakes drama a massive disservice. The Great War deserves our respect, but also our curiosity, our passion and our dice.

James: For me, it’s the focus on the Western Front and the associated imagery. The First World War has such a reverence in the popular mind in large part because of how obscene the damage was to both life and landscape. But the war was far more than just the battered fields of France and Belgium. It stretched as far as Russia, to the Middle East, to Africa, the Pacific, and beyond – a true world war – and each of those areas are hugely fascinating and engaging.

However, perhaps a bigger bugbear for me is how we tend to assume the generals didn’t really know what they were doing. Industrialised warfare on this scale was new, and whilst the cost of the learning was enormous, by 1918 you had the genesis of so much of modern warfare. So many of the successes of that final year were the result of commanders trying something new and learning lessons. Many generals were incompetent and callous, but many were also trying to navigate this new era of warfare with as much tenacity and ingenuity as they could muster.

GH: Sam, earlier this year you wrote an excellent article about WW1 called “The War Non-One Wargames”. What do you think it will take to bring WW1 into the mainstream of wargaming along with the big boys (WW2, Napoleonics, etc.), or is it forever doomed to be a niche wargaming subject?

Sam: There are a few things which have massively helped Napoleonics and WW2 wargaming to get to where they are (Ancients too). Both benefit from fiction and non-fiction being replete with high-quality media of all types to engage and sustain an audience. Both are supported by a healthy ecosystem of competing manufacturers producing huge ranges of high-quality plastic miniatures. And lastly, both are supported with a wealth of ‘modern’ rulesets that allow gamers to try-out and coalesce around systems that they love to play in a variety of scales and contexts (although, in the case of napoleonics, there are perhaps too many choices!)

WW1 clearly has a bit of catching up to do on all of these – although there are certainly many positive signs across the board, such as the plastics being released by Wargames Atlantic and the new groundswell of rules development. Additionally, the Great War also seems to be weighed down by its own particular albatross – as mentioned above – how it is remembered. This feels like it is changing, but only slowly. I think perhaps it is unrealistic to expect WW1 to reach the heady heights of WW2 or Napoleonics, but it should be a hell of a lot more popular and widespread than it is! Perhaps we can aim to overhaul something more manageable, like the English Civil War or Dark Ages, and then see what happens next?!

GH: How can our readers stay up-to-date with 1918 or get involved?

James: We’d love Goonhammer Historicals fans to jump on-board! We’ve just launched a Patreon here where you can gain early access to the rules, join the playtest and take part in our 1918 Discord community. Consistent patreons will also get a digital copy of the finalised rules (effectively at a discount!) when they are released later this year. So there’s no time like the present.

Sam: You can also hear us talk more about 1918 on the Hobby Support Group podcast, available here, or shoot us a question in the comments on this article, on Discord or on social media (@warfulcrumgames) if you have any questions.

Many thanks to Sam & James for taking the time to talk to us about 1918. I’m definitely looking forward to giving them a shot, especially as it’ll finally give me an excuse to put an entire company of my beautiful blue-coated Frenchmen on the board!

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.