The mightiest brains and most strategic minds in the Goonhammer Historicals team have been talking hex and chit games recently. Possessing neither, only the meagre powers of an editor, I thought I’d give one a go and see if there’s anything the perfectly smooth brained (i.e. Me) could learn from miniature wargaming’s older, smarter, cousin.

Napoleon’s Eagles is the digital version of a game famous under another name – War and Peace, one of the great hex and chit Napoleonics systems. It’s well known for balancing length and complexity, giving you ten scenarios to fight out the Napoleonic wars from Revolution to their bitter end in chunks of two to four hours of gaming. A tight and easy to understand ruleset scales well as scenarios grow into the most famous campaigns and, while a fairly old system now, it’s still well beloved – and much played. Lacking table space and with a child old enough to definitely reach up to the kitchen table and stick a Marshal or two in his mouth, I’ve been playing the digital version (available on Steam) – the same game, but it fits onto your screen.

It is important to note at this juncture that I absolutely suck at this game. I don’t mean that I’m bad, oh no, much more than that. I am terrible, just beyond terrible, at this game. I have watched every tutorial several times. I have read through the tables, rules of the grand campaign from diplomacy to prisoners, I have made extensive notes. I can, just about, limp through the introductory scenario – Napoleon’s first Italian Campaign – and secure victory for the French, albeit in much worse shape than the man himself. I can fight out the Egyptian campaign to a bloody failure (not far off history there, to be honest), but any larger than that and I can’t keep track of it. That’s no fault of the game – the mechanics are there, the arrows of cruel and outrageous fortune fall where they may – but I simply lack the vision of a great general, the kind of mind that holds all this in place so that they can, for example, know what the hell to do with a blocking army in Northern France so that Paris doesn’t fall within three turns of starting the game.

Far from being a cry of “help me please, anyone”, I’ve learnt a lot about games – and the Napoleonic period – through unrelenting, pathetic, failure.

Getting Good – The Italian Campaign

As mentioned above, the tutorials, guides and manual for Napoleon’s Eagles are all very comprehensive, extremely useful and surprisingly clear for what I thought would be an outrageously grognardy game. The UI and the controls are simple – drag, drop, confirm. So it’s not the game that is causing me to suck at this to such an extent. It’s me, and to a lesser extent, the history.

Let’s take the Introductory Italian Campaign as an example. Napoleon, loaded up with close allies, a fat stack of infantry and some handy cavalry, simply has to march across Northern Italy to threaten Vienna. As in real life, his opponents are old, slow, and idiotic.

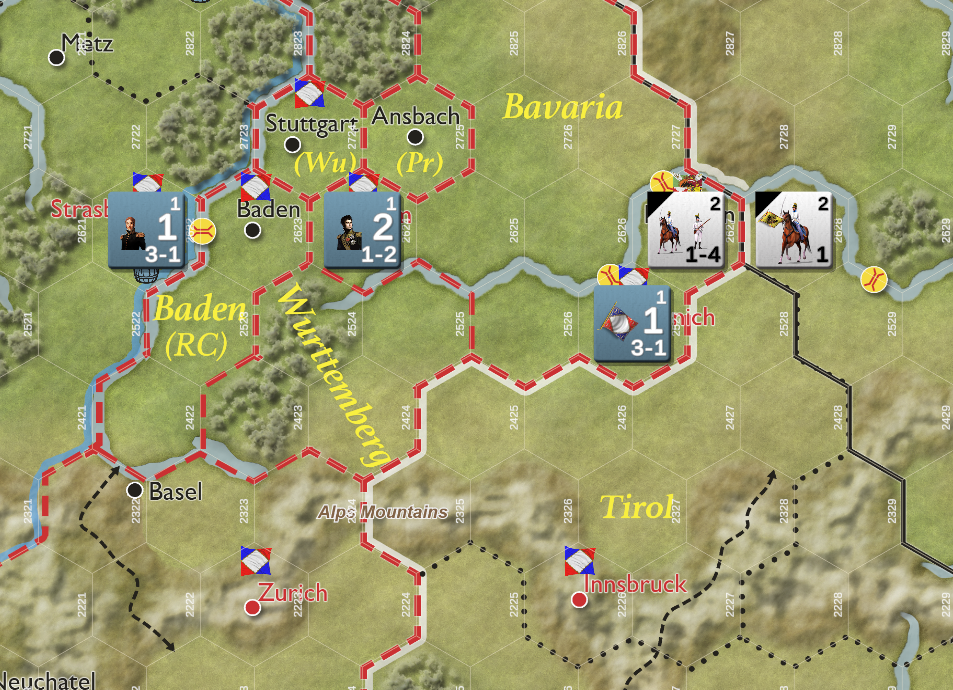

Above is Victory – one more turn and it’s an almost sure-fire thing. Outflanked by Napoleon marching across the northern Italian plain, with backup armies surrounding and neutralising the main Austrian forces, one more battle and Napoleon will break through to wreak havoc on the soft underbelly of the Austrian Empire. I can get to the above, more or less, nine times out of ten. Occasionally I’m too slow – and lesson learned there, I have to fight like Napoleon, hard and fast, forcing a decisive battle by splitting the enemy and taking every opportunity.

So, when the focus is tight, and no-one’s trying to invade France, I can beat the Austrians most times. “Most” bodes badly.

Marengo

With the Italian Campaign mostly in the bag, I move on to Marengo – a more challenging campaign over the same ground. Here, the French must either hold in Italy and swing through Bavaria and the Tyrol to neutralise Austria or follow Napoleon’s original plan by punching through the remains of Italian Austria to march on Vienna. I, in my infinite wisdom, attempt to do both.

That’s another lesson learned about Napoleon’s victories on a campaign level. Without focus, without a single burning aim and ambition, you end up scattered, fighting equal forces all over Europe instead of massing a significant army, pushing them to the limit getting them to where you need them to be and focusing in on your victory conditions. This time, I let Messena off the leash instead of forcing him to hold Genoa in the face of insurmountable odds, gambling on an all out assault to break the Austrians before Napoleon could arrive from Paris. It all relied on one battle, Soult and Massena, the greatest of the Marshals, against the aging Michael von Melas. One battle and the Austrians are done.

What the SHIT Messena.

This is where my plans start to fall apart. Unlike Napoleon, whose fatal enemy was hubris and Toussaint L’Ouverture, mine is distraction. I can get to maybe turn 5 of the Marengo scenario before things like “well, this army could secure my flank in the long term by moving here” override considerations like “Victory is on a time limit” and “Napoleon never waited for anyone”. It leads to situations like the below, where Messena, fresh off his important job of being beaten by crap Austrians, has nipped down to Florence for a jolly, when Venice (victory condition) is lightly held by some Brits who are in the wrong place at the wrong time. This loses me the game after two hours of play.

This kind of thing happens to me in hex and chit games all the time. I think I’m playing the long game, the diplomatic or strategic game, taking Florence to put additional pressure on the Papacy to reconcile with Revolutionary France, because somewhere in my brain a switch has been flipped to “strategy”. But that isn’t the game – it’s strategy, and it’s damn good at it, but it isn’t played out in the staterooms of Paris and Rome. Massena should be doing his job – instead, I strongly suspect he’s been looting again.

Worse than distraction is the forgetting. I don’t know how big hex players manage to keep it all in their minds. Every time I’ve played the larger scenarios, there’s an corps or two that I just completely forget about – maybe they’re amassing a doomstack in Paris, or, in the case of this last oh-so-nearly successful Marengo run, they’re Moreau and Lannes, sat in Strasbourg the entire game while an unnamed and clearly extremely brave divisional commander captures the entire bloody Tyrol.

Egypt

I was going to end these slight after action reports there and move on to “why you should play some hex and chit even if you only play miniatures”, but I thought I’d apply these lessons and learnings to a scenario that beats me every time: Egypt.

The Egyptian campaign is a strange – indeed near inexplicable – bit of colonialist nonsense. Napoleon, fresh off becoming a celebrity in France, decides to take a good chunk of the French Army, many of his greatest hangers on, and most definitely not his wife, off to Egypt to nebulously threaten British India. Faced with the triple threats of dehydration, plague and the “find out” part of “fuck around” delivered by Nelson at Aboukir, Napoleon flails around for a bit, abandons his army and has his personal life exposed to the British Press.

This time, applying the lessons of focus, speed, and not putting all my eggs in one basket unless that basket is Napoleon himself, I’m going to do better. Importantly, and unusually for me, I take my time to plan out the campaign. Napoleon will take the army and his generals to Cairo, before splitting into three forces: Napoleon (red) with the bulk of the Infantry to menace the Ottomans, Lannes (Blue, with Murat) and the Cavalry to sprint down the Nile to capture Aswan, and Kleber (white) to hoover up reinforcements and keep Alexandria locked down.

Carefully scouting out the enemy is a key part of this – the Mamluk armies are low skill and low morale – they’ll consistently lose a strength point every time they’re brought to battle and usually withdraw. If we keep hitting them hard and fast, Lannes and Kleber should be able to take all of Egypt, while Napoleon uses his higher skill army to hold El Arish against a phenomenal amount of Ottomans.

A year later and the plan has worked – Lannes chased down the entire Mamluk army across the length of the Nile, Kleber temporarily lost Alexandria but took it back in the end, and Napoleon has been weaving back and forth across the Palestinian border sniping out scattered Ottoman armies.

The final Victory positions – everything in the upper and lower Nile in French hands. A strategic victory, but an utterly pointless one. With Focus, speed and Napoleon I’ve only won a marginal victory in the end, but it is a victory nonetheless! It might not matter a single bit for the wider war, because what the hell do the French do now, masters of Egypt but unable to get out with the Med in British hands, but we’ve done it. The second easiest scenario, in the bag.

What I’ve Learned

There is a point to all this, honestly. I’m not much of a hex and chit gamer, owning a few games on steam (like this one) and a very beat up copy of Starship Troopers. Nevertheless, this has been a fantastic experience – fun in and of itself, and a real challenge, but also of great use to the tabletop gamer. The lessons I’ve learnt playing this are widely applicable to my terrible record of losing games in whatever period or scale. I don’t tend to plan out my lines of attack before the dice start rolling. I never focus on what I need to do to win. I always trust my underlings more than they can handle (I’ll say it again, Dear Child of Victory my ass). Playing Napoleon’s Eagles has shown that I do this on any scale, exposing some real lessons I can learn to make my tabletop experience better.

Applying them to something like Sharp Practice is easy – don’t throw your forces forward piecemeal, wait for high ranking leaders to launch assaults rather than throwing single flag sergeants into combat, and decide what you’re going to do on turn one rather than reacting to the enemy. These are all simple things when you think about them, but Napoleon’s Eagles lets me try (and fail) in an hour or two rather than over the course of a long and painful afternoon of painting.

I’m left with a greater and deeper understanding of the challenges of Napoleonic warfare at scale as well. The Marengo scenario starts with Napoleon in Paris, planning his great feint to fool the Austrians into throwing forces north. Making that choice – and consistently making the right choice (until he made very wrong choices) was his genius, and the difficulty in recreating that genius in my own moves, even with the near perfect information of terrain, morale and enemy positions, is telling. Seeing the big picture and making the right move, at the right time, with the right forces, seems above and beyond the scale of 28mm skirmish wargaming (and to an extent it is), but the lessons are the same. If you’re like me and wedded to painting and modelling, go try out some hex and chit in your period of choice – you’ll be a better gamer at the end.

With that, I’m off to try the Austerlitz scenario – surely pretty simple, right?

Mon dieu.

Have any questions or feedback? Notes on how to even approach the Austerlitz campaign? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.