As part of our dive into hex and counter games, I wrote a two part series on my favorite game system. Part 1 is about why I like these games so much. Part 2 will be on which games to try to jump in and try to see what all the fuss is about.

Board games are about people. With rare exception, I don’t enjoy playing games alone. The cardboard, the plastic, the wood…it’s all just stuff without friends sitting around the table with you. My favorite games are the ones that rely on your opponents to provide the challenge and the interaction. Even then, so-called multiplayer solitaire games don’t do it for me. It isn’t enough for an opponent to provide a changing puzzle for me to play around. I want anger, elation, and joy. I want betrayals and vendettas, alliances and nemeses. In other words, I want people. I want human interaction with all its messiness in my games.

So, what does that have to do with COIN? Well the best games are the ones that draw that out of us. That stress us out and push those emotions to the breaking point. COIN does that. COIN games build that right into the victory conditions so that you have no choice but to look up and engage with your opponents on a visceral level. You’re going to mislead and lie. You’ll make promises you intend to keep and shrug apologetically when later you’re forced to break them. Leaders will rise and fall along with your emotions, in part because Volko Runhe decided there are better ways to measure victory than a comparative points track.

I’m going to use A Distant Plain as my primary example because it is both my first and my favorite COIN. ADP is set against the background of the modern conflict in Afghanistan. One player will take on the role of the Coalition and another of the Afghan government. Ostensibly these two are on the same side but their victory conditions are just different enough to put them in occasional conflict. The Coalition player wants the population of Afghanistan to support its government and to get pieces off the board – “bring the troops home” if you will. The Government player couldn’t care less about support so long as they have control of the population. This is a subtle yet deeply important distinction both in the game world and our own real one.

For most of the game the two will work in tandem. US troops will shuttle around the board rather freely, dragging Government forces along with them. This massing of troops will provide the Government player with the control they need so usually they’ll agree. In exchange the Coalition player will use Government funds to train additional troops and win over the hearts and minds of the Afghan people. It’s a nice little relationship – until suddenly it isn’t. Emboldened by Coalition forces withdrawing from the board the Government player may begin to build their alternate victory counter, Patronage, which is a measure of corruption. No population particularly enjoys a corrupt government and so slowly Governmental Support is siphoned away. Meanwhile, the Taliban player lurks in the shadows and Warlords cultivate opium under the safe cover of instability.

That push and pull between allies and enemies drives the play COIN games up off the table into the space between the players. Trust, real trust, is required among allies which makes the inevitable betrayal all the more painful. Cities fall, people die, and revolutions are quashed under the weightless words of “Sorry, but you’re going to hate me after this move”. While the details change from title to title to match the setting, the social play does not. Cuba Libre, the simplest of the first 5 titles, doesn’t have the cross-linked goals or even the victory conditions directly shared by allies in Liberty or Death. This doesn’t affect the drama of play.

The game begins with Batista’s government at the height of their power, and Castro’s rebels secluded in a corner. The Directorio will have to ally with Castro temporarily, and everyone will attempt to curry the favor (and money) of the US Mafia. Victory conditions aren’t linked like in ADP, but everyone wants to win. That drive pushes alliances before tearing them apart. The Taliban will detonate a bomb, Castro will burn things down. And that’s when COIN hits you on the other side of the head. These games are about people, but they’re also about real people.

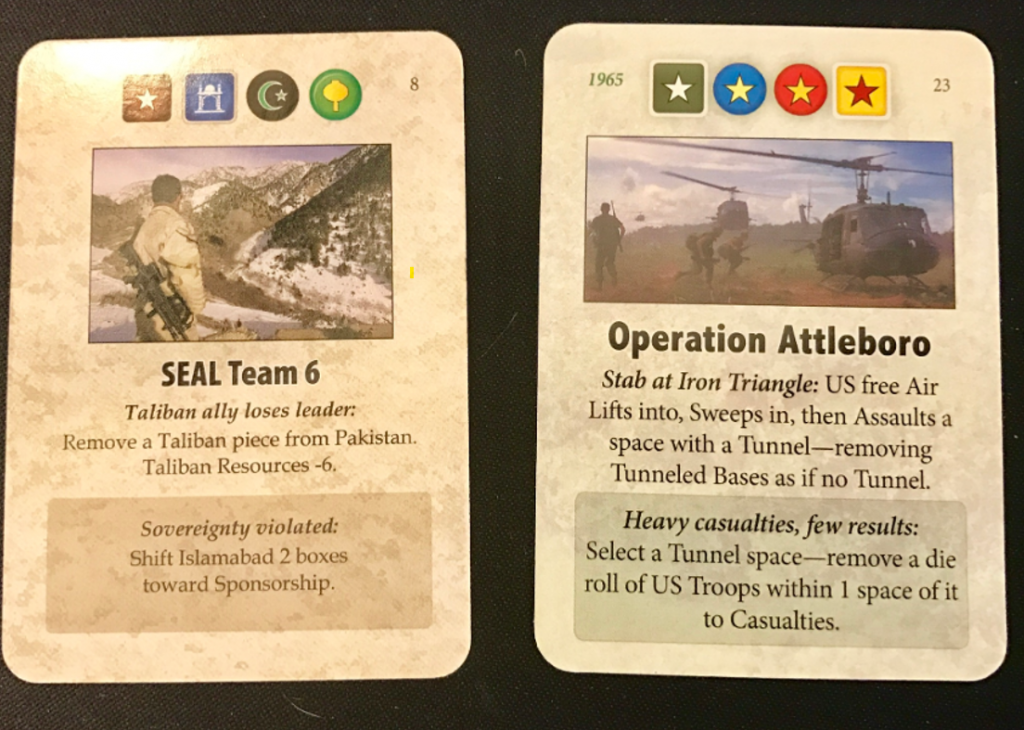

I posted a picture of Cuba Libre the first time I played it, and a Cuban friend replied almost immediately: “Kill Castro for me.” That was eye opening. Here I was making mojitos to drink while playing and just the box image conjured up a very real experience for a friend. Something similar, though less directly personal, happened the first time I played A Distant Plain. The board is full of familiar names. Kandahar, Helmund, Kabul, etc. I’ve heard those names since high school and here I was playing a game about them. It keeps going as the cards flick out. There’s Seal Team 6 right in front of me with two different readings on the event.

They say “History is written by the winners.” The present is also told through a skewed lens. My entire concept of the modern conflicts in the Middle East was skewed, and is skewed, by the news I read and listen to. While nothing is free from the influence of its creators, the COIN games at least present two interpretations of every event. The cards that serve as the beating heart of this system are all tied to real things or events and all offer a choice. When a player resolves an event, they choose which interpretation becomes real in your game world. One half is typically beneficial for the insurgent factions, the other for the Counter Insurgents.

Seal Team 6 either eliminates Taliban operatives in Pakistan (normally extremely difficult) or it angers Pakistan and moves them towards opposition with the Coalition forces. Operation Attleboro – a Fire in the Lake card – provides either a “Stab at the Iron Triangle” and the removal of VC forces or “Heavy casualties and few results” for the US. This two sided approach to the conflict is a big part of what draws me to this series of games. If you’ve listened to our podcast for a while then you know by now that Charlie and I have a lot of fun playing games, but we also think games can be for more than just fun.

From the haunting emotions that can come from The Grizzled to the revelation I had when I realized I was playing A Distant Plain the way CNN shows conflict, games can be more than just games. I talk about COIN games because I love COIN games, and I love COIN games because they teach me something about the world and – at least once – about myself. A game that can do that while still providing the joy and fun that comes from sitting around a table and yelling at your friends is a special one.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.