For better or worse, Ubisoft Montreal has had its finger — or whole hand? This metaphor is kind of gross — in the pot for almost every important game that its parent company, the world-bestriding AAA game development titan Ubisoft, has made in the past twenty years. After a couple get-me-over, get-me-up-and-running games (Ubi Montreal was responsible for a number of Disney products and the licensed Batman: Rise of Sin Tzu title, for instance, none of which will ever be covered in this space), they became one of Ubisoft’s global heavy hitters. Ubi Montreal at least touched just about every Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell, Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six, Prince of Persia, Assassin’s Creed, and yes, Far Cry game that came through the company, and in the vast majority of cases was the lead studio on all of those projects — which makes sense, because currently Ubisoft Montreal boasts well over 3,000 employees, making it the largest single video game development studio in the world.

That’s a lot of games! A lot of games that fundamentally are very, very similar in each iteration, and clearly claim a great deal of institutional memory at Ubisoft Montreal. Assassin’s Creed (2007) and Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla (2020), for instance, are a sort of model ship of Theseus for the company: the two games essentially have nothing to do with each other, play radically different, have completely different values as games nominally in the same genre…but from iteration to iteration, each of the 10 other major installments of the franchise between them still flow well, explaining how development of those values occurred. In AC’s case, what happened is they first helped create the third person character action genre, then sat back and integrated the best things that other companies did with the genre back into the product — most notoriously the loot model from Diablo and Destiny, and in the most recent installment, a passive skill tree and a full-on Souls-like stamina meter.

This wasn’t the case with, say, the Far Cry series — or that is to say, it only became the case later on in the franchise’s life, and the Far Cry franchise can never be said to have driven development of the FPS genre, really. While Ubi Montreal shepherded development of the first two titles in various ways, Far Cry and Far Cry 2 were very strange, misfit titles, sometimes feeling more like tech demo than actual game, and it wasn’t until Far Cry 3, with its Alice in Wonderland framing and slick, attention-grabbing opening scenario and villain (Vaas Montenegro is, in spirit, one of many proud offshoot iterations of the f-f-freakin’ Joker that have appeared in the culture since the turn of the millennium) that a formula became standardized. And lo: the great Giancarlo Esposito will be fulfilling this role in the upcoming Far Cry 6, which seems to think it will have some things to say about evil Latin American dictators. I’m not particularly holding my breath.

Far Cry 2 existed in a liminal state between where the franchise started and where it eventually ended up; the very original game in the series wasn’t even made by Ubisoft Montreal, but instead by the Crytek people, and was an intentionally-campy 80s action romp through a vast open-world island full of mutating beastmen with superpowers experimented on by ex-Apartheid South Africans. Ubisoft Montreal remade the game for the original Xbox under the title Far Cry Instincts, as the console couldn’t handle the open-world gameplay that the PC title promised and rather than go the Morrowind route, Ubisoft just decided to make the game more linear and plot-driven.

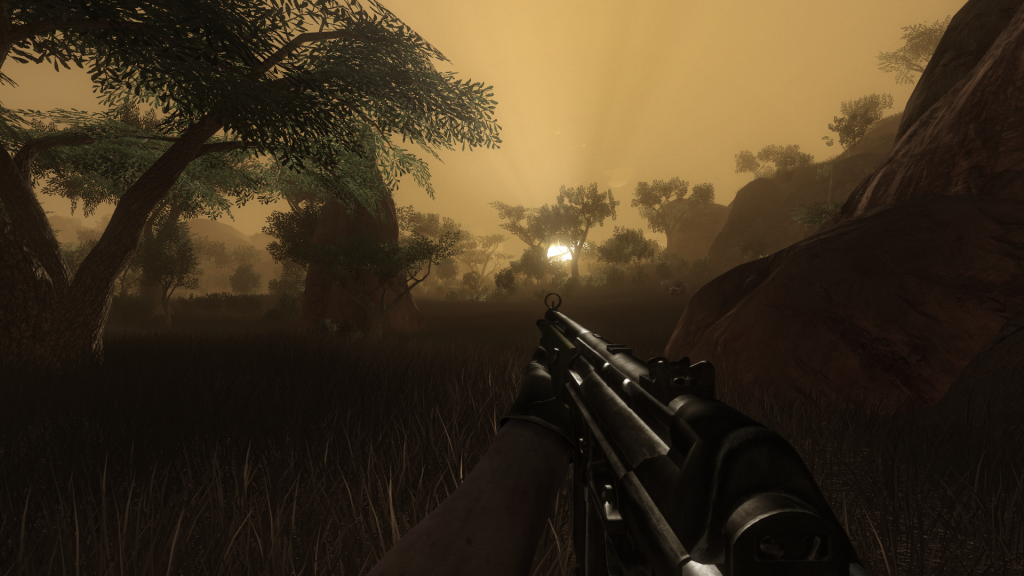

This meant that Far Cry 2 was Ubi Montreal’s first real shot at an open-world Far Cry title, and the results are still interesting to this day; for one, it still looks incredible. There’s less asset density than you’d expect to see in a modern game — much less — and therefore fewer trees, random rocks, bushes, and so on; but this works fine in the game’s scrubland, savannah, and desert mini-biomes, and the title gets by in the wetlands and jungle areas. What remains tremendously impressive is the lighting engine and the way that engine is put to work with the day-night cycle; time of day was an important part of the game’s look and feel when it released, especially sunrise and sunset (we’ve discussed the relative aesthetic importance of those parts of the cycle previously in this space).

The plot of the game…is what it is. It’s generally frowned upon now to make “are we the baddies?” style games that also stake out their core gameplay loop on the motions of being the baddies, but Far Cry 2 is sufficiently aware and frank that you, the protagonist, are in fact a bad person. The flimsy overplot thread is that you’re hunting a weapons dealer named The Jackal — yes, the famous fictional Cold War assassin that Bruce Willis among others has played, this time repurposed as a Colonel Kurtz-type figure, driven mad by his own primitive evolutionary biology ideology and maybe a bit too much Nietszche. Your character, which you can pick from an array of scumbags from across the world ranging from “nihilistic and dangerous American thrill-seeking cowboy” to “Islamic terrorist” to “guy the IRA kicked out for causing too much collateral damage,” doesn’t actually matter except for which hand models you’ll have holding your firearms; no matter which you pick, you land in-country and are driven into town by a chatty cabby past ominous scenes of a civil war in its now-openly violent stage…and immediately contract malaria. The Jackal finds you in your hotel room, intending to kill you, and instead laughs, steals your job brief, and after a brief villain speech leaves you to deal with your sickness.

And outside of audiologs, that’s it’s for the Jackal for the next ten to twelve hours of gameplay, more if you decide to ignore the main quests which develop by working for one of two explicitly interchangeable factions that you, as a foreign mercenary, only care about bilking out of as many conflict diamonds as possible. Yes, the currency for this game is diamonds recovered from briefcases in wrecked cars or under bridges or under lockdown in mercenary camps; the game is not particularly subtle with these metaphors, nor is there any reason that it should be. About half of the men you shoot and kill aren’t natives of this fictional African state at all; they’re very clearly Rhodesians and Boers, with the shorts, accents, and entitlement to match; a constant reminder of the international element to the background hum of the war industry that has consumed the nameless nation. Eventually, that hum comes to the fore, as the mercenaries, seeing their revenue streams run dry, team up to coup both factions and install a colonial corporate government to take over the diamond mines as the game moves to its conclusion.

More important and more relevant to a player revisiting the title in 2020 than the plot are the limitations that the plot places on the player: you are a sick piece-of-shit dead-ender would-be assassin in a regional backwater trying to make life worse for everyone on your way to a payday, and no one wants you in-country. There are no “allied soldiers:” everyone you meet outside of a cease-fire zone sees you and immediately clocks you, correctly, as hostile — regardless of how many missions you’ve done for their faction, not that there are legibly consistent uniforms anyway. There is no fast travel, outside of five bus stops placed around the map in the four corners and in the center. There is no minimap in the UI; you have to navigate by physically pulling your map out and flipping through it. Guns constantly gum up and jam in the oppressive heat and humidity of Central Africa. Routinely, and occasionally in the middle of combat, you will be overcome by malaria and have to treat it. There’s a whole lot of procedurally-spreading fire in this game, which combined with dry grass, molotov cocktails, and a preponderance of explosive caches can easily lead to swift and surprising death. If you get stuck somewhere with a gun that doesn’t work and no meds, your only hopes are that you’ve got an AI buddy — one of the other mercenaries you could have chosen at character generation, usually, though the only two women buddies in the game are NPC in a tediously Ubisoft quirk — or that you can walk to the nearest safehouse, and either have cleared it already or have the capacity to defeat the men with guns squatting there already.

It’s interesting: this is in many ways a blueprint for what the series would become — the Jackal is a prototype for all the theatrical villains who’d eat up increasingly large chunks of the following games’ openings, while the open-world trappings with cars, boats, and gliders and semi-procedurally generated AI patrol routes presaged the cloying take-and-hold-territory gameplay with freedom fighting gloss that titles from Far Cry 3 onwards would latch onto. This game, however, doesn’t really bother trying to trick you into thinking you’re some hero of the revolution giving people their homes back; the only territory you seize are safe houses, places for you to stash guns and get some shut eye before going out and making some more money.

There are a couple of things that haven’t aged well on the technical side; one is just an artifact of running an old game on a modern system — there are a number of animation glitches for character models in scripted plot sequences, most of which are limited to having mission givers weirdly shake their heads at you while speaking or float around the room while trying to walk somewhere. However, it can get a little tiresome when your buddy clips into a tree while you’re trying to heal him. Generally speaking, these aren’t major and don’t overly disrupt the experience. The game wasn’t made to play well with dual monitors and alt-tabbing either, but as long as you remember every developer’s favorite undocumented fullscreen hotkey alt+Enter, that’s fine too. The biggest disconnect a modern AAA FPS player will have going back is how little attention is paid to sound design; guns generally sound hollow, high-pitched and with little bass. There’s a historical issue with Hollywood and video game devs padding the bass levels of rifle round fire (and using rifle round fire for pistol round sounds) to make their weapons feel more weighty and theatrical but that’s not really what’s going on here; it feels more like a mixing problem. Furthermore, the mechanics of gunplay have evolved greatly since 2008; it feels a bit odd in 2020 to be able to aim down sights with a G3, strafe right, fire seven rounds on full auto, and still be putting damage on target with the final one.

Other than that, though, if you’re looking with something with a little more restraint than the most recent installments in the Far Cry series — and certainly a change of pace from the endless setpiece spectacle campaigns and battle royale monotony of the Call of Dutys of the world — Far Cry 2 remains an incredibly playable, beautiful game that will challenge you to get that shitty 1972 yellow Citroën coupe from the burning hell that used to be the Police Station back to the bus-stop.

Final Verdict:

This game retails for $10 on the Ubi Play Store and routinely goes on sale down to around $3; if you haven’t played it and you like these games, you owe it to yourself to grab the title.