Welcome to the Century of the Vampire, an ongoing weekly feature where Goonhammer managing editor Jonathan Bernhardt watches some piece of vampire media, probably a movie but maybe eventually television will get a spot in here too, and talks about it at some length in the context of both its own value as a piece of art and as a representation of the weird undead guys that dominate western pop culture who aren’t (usually) zombies.

Last week, Bernhardt reviewed the 1922 F.W. Murnau film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Today, he looks at the 1979 Werner Herzog film, Nosferatu the Vampyre. This article will contain spoilers.

Nosferatu the Vampyre is an odd duck, much like its director, its lead actor, and definitely like the ethos that surrounded his shoe-string production that clocked in at under a million dollars in budget and flooded a small town in the Netherlands with eleven thousand rats that Herzog swears they did their best to control. It is most remembered, like almost all actual Dracula or Nosferatu films are, for the performance by the leading vampire; here, the temptation of that sort of ego boost is what drove notoriously difficult, abusive, and violently unreliable actor Klaus Kinski to once again stomach working with a director he both needed and hated for the biggest role of his career. That makes him an excellent place to start.

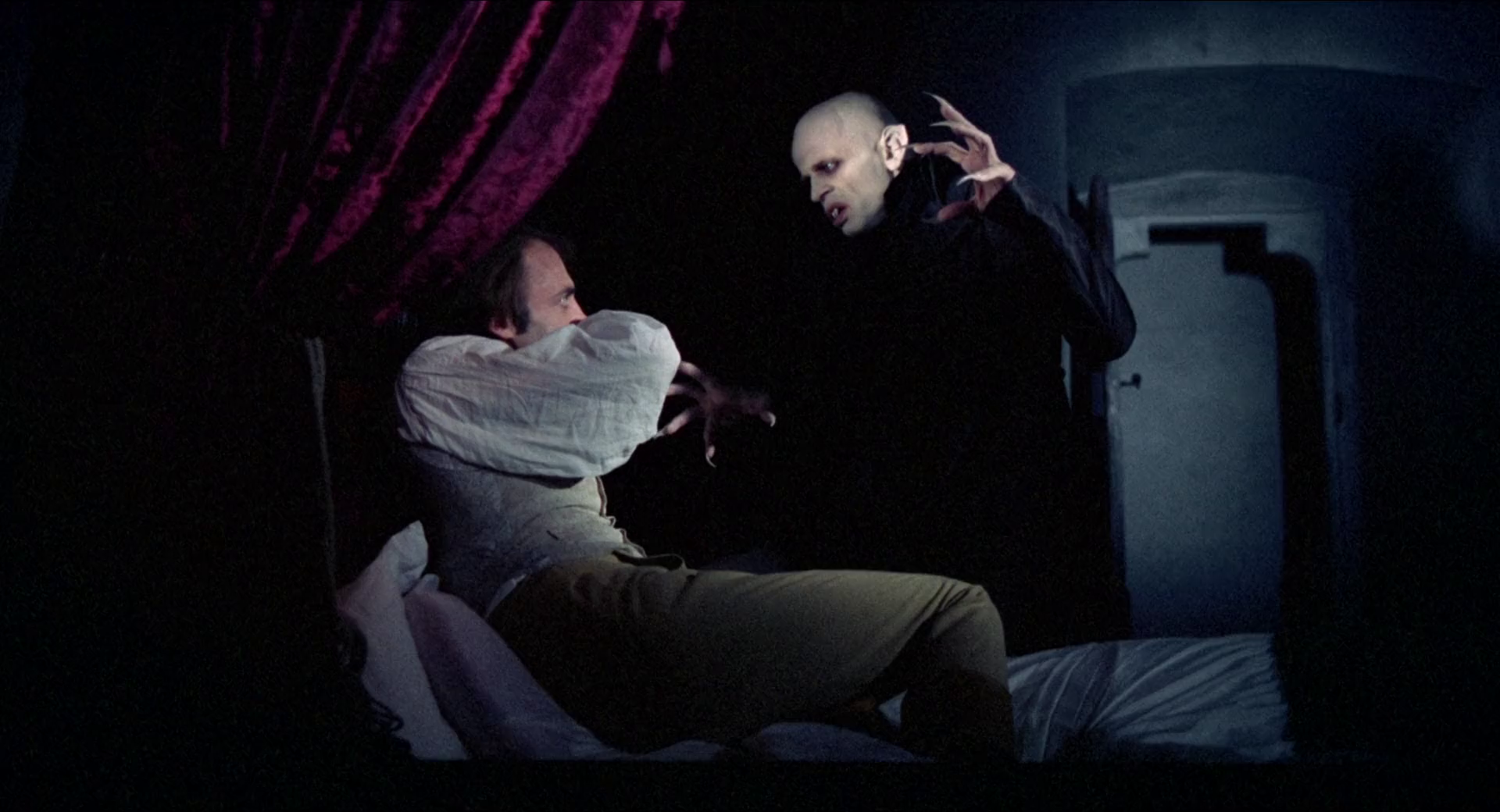

On the surface, Kinski’s performance as Dracula intersects little with the man himself being a vainglorious monster, which is by design; Herzog has talked at length in many venues, including his own commentary track on the film, which you can watch for free on YouTube with the German cut of the movie, about the fights he had with the actor on set to literally tire him out and get him to play a less openly malevolent, less demonstrative, and less active vampire. The one real flash of the kineticism that Kinski wanted to give to the role comes through in the tense moments after Harker cuts his thumb, as the Count hurls aside the chair Harker had been sitting in as he closes the distance between them, backing Harker towards the fire. Herzog wanted it there; he did not want it anywhere else and, in his telling, he ensured that he got it nowhere else. For the bulk of his time on screen, this vampire is mostly…suffering from major clinical depression.

Herzog wrote the script, and so the principal characters — Lucy Harker and Dracula — get to speak in sort of first drafts of the sweeping, grandiose proclamations on the nature of the cosmic that he would become so famous for in his documentary narration. “Death is overwhelming; eventually we’re all his,” Lucy says after Dracula comes courting, introduces himself and protests her accusation of fatally attacking her husband, saying Jonathan Harker will not die. “Stars spin and wheel in confusion. Time passes in blindness. Rivers flow without knowing their course. Only death is cruelly sure.” Dracula considers this for a second; his lip twitches, and he doesn’t quite smile, but he starts in with his own Herzogian rejoinder, seemingly happy to have found someone else who will Talk Like That: “Dying is cruelty against the unsuspecting. But death is not everything; it is more cruel not to be able to die.” They go back and forth like this for another minute or two, with Lucy eventually taunting him with her ‘lovely throat’ and then dismissing him, but this is the crux of the conversation.

It’s the second time Dracula has brought this up, his desire to die; in the most basic, plot-functional way it’s a double-proof explanation for why the vampire sticks around to feed on Lucy even as dawn begins to break and the rooster crows. But more importantly it strikes at the character’s fundamental loneliness and alienation outside of the natural order, no matter how totalizingly brutal that nature is, and indeed explores the ways in which that alienation allows him to sit in contemplation of that order — which has been a theme for Herzog for much of his career, no matter how much the man swears off metaphor in his work. When Dracula gives a similar speech to Lucy’s husband about the “abyss of time” that swallows up eternals such as himself, Jonathan sits there in dumb silence until the matter of the contract for the estate comes up, at which point he finally speaks in order to quibble over price. He doesn’t understand the nature of the living world the way his wife does, and he certainly doesn’t understand alienation from that nature the way the monster who wishes to take her from him does — but he’ll get there by the end of the film.

The expression of the vampire’s hunger in both the 2024 Eggers film and the 1922 Murnau is best described as “animal” or “atavistic.” In the Eggers it is simply referred to as “appetite,” an unthinking, mindless need to consume, and Murnau renders it even more base by comparing it to the natural function of Venus flytraps and polyps; Herzog saw in Murnau’s Orlock the empty soullessness of the insect. His Dracula is much more human. While the vampire feeds on blood, this is yearning — a hunger attached to emotion and higher brain function, while still not being the full-throated tainted romance of, say, the 1992 Coppola Dracula film. It humanizes Dracula in a very effective way, this soliloquizing about death and want and alienation from both. It also makes him much less scary in a scene-by-scene visceral sense, which is where Kinski’s dissatisfaction came in. This Dracula has great pathos, but he is, in fact, pathetic.

He is also playing second fiddle by the end of the film. Isabelle Adjani as Lucy Harker takes full command of the picture once Dracula makes his journey by sea to Wismar, bringing the plague with him and setting off panic in the streets. In this version of the tale, Jonathan Harker is a fool to leave the sanctuary that takes him in after he is found on the grounds of Castle Dracula; by the time he arrives in Wismar his mind is gone, succumbing to the vampire’s curse, and Lucy — briefly stymied at home by a pompous, fully-useless Van Helsing who insists this will all blow over shortly — is left to unravel the mystery of the vampire herself. It is she who divines the rituals and remedies to “protect” Jonathan and block Dracula from returning to his coffins; it is she who visits Renfield in the asylum and determines his guilt in sending her husband to his fate (a fantastic rendition of the character from Roland Topor); it is she who realizes the ultimate sacrifice she has to make in order to stop the plague. She does this with an abiding calm and deliberate seriousness that counterpoints the town and the old men who run it losing their minds; this culminates in what is for my money the most unnerving scene in the film, the plague festival that Lucy runs through out in the city square, where those infected with the plague and doomed to die dance and feast among the thousands of rats that Herzog unleashed on the Dutch town where he filmed the Wismar scenes, culminating in a last supper for the damned where the rats overflow the feast table itself.

In comparison, Kinski’s Dracula gets a bit silly with it. The coffin-carrying scene from the Murnau film is back but this time there is also a long shot of our vampire Naruto-running across an open square with his cape billowing goofily behind him; the one scene Renfield gets with his master has Dracula openly pouting about Lucy’s rejection and feebly pushing the clingy Renfield off him with a “Nyeh.” This is appropriate; in understanding the monster, Lucy has already prefigured his defeat (in this form at least) — Dracula’s power wanes and he approaches his final reckoning, even as the Nosferatu demon remains strong. (It is brief, but the demon which inhabits the count is given its separate, titular name in the film, during perusal of the folklore book that Harker gets in Transylvania.) Dracula sends Renfield north to spread the plague elsewhere and sulks off to the endgame.

This progresses much in the same way it always does — Lucy/Ellen lures Orlock/Dracula to her bed to feed willingly, then captivates him and keeps him there as the rooster crows and the rays of the dawn destroy the monster — with one crucial difference from both Murnau’s Nosferatu and Stoker’s Dracula: The fate of Jonathan Harker. He’s stirred from his brain-fevered slumber and seems to be regaining energy, but looks paler and more deathly than ever. Lucy crumbles up communion wafers in a circle around his chair in order to keep Dracula from him and drive him upstairs to her, but she does not realize what is happening even as she and the vampire lay dying in the dawn: Jonathan Harker is turning! We’ve got our first turned vampire of this essay collection. It will not be our last; fascination with the process of becoming a vampire and other matters of vampiric reproduction are among the biggest additions to the tropes and genre language of vampire film in the back half of the twentieth century.

By the time the incompetent Van Helsing arrives and realizes how badly he’s bungled matters, Harker is fully awake and alert. He sees the professor go upstairs with a hammer and stake to finish off the count, and shouts for help as he feels the stake upstairs pierce his own heart as well. Here the film goes fully off into dark comedy, as the constable arrives to catch Van Helsing literally red-handed moments after Dracula’s final death, and he and a member of the watch argue for a few minutes over how they’re to arrest Van Helsing if the judges, mayor, and guards at the jail are all dead. They resolve eventually to just figure it out when they get there and walk out with the professor in tow; the vampire Harker gets the maid to clean up the warding circle around him, now keeping him imprisoned, and then tears off his crucifix necklace and reveals two tiny viper fangs growing from his front teeth as he demands a horse…and sets off on his next adventure! Dracula was neither lying to Lucy nor mistaken when he said her husband would not die; but he did not tell her he would live.

On the whole, Nosferatu the Vampyre is a film that makes me glad I have not committed to ranking these things in a list, because right now I’d be doing a bit about how at third place out of three, it was the worst vampire movie of all time (of the last month). And that’s not fair! I liked it enough to immediately rewatch it a second time with the director commentary. It’s immensely engaging and moody right from the famous opening with the mummified cholera dead that Herzog filmed in Mexico for Lucy’s nightmare; you want to be watching on a screen and medium that really gets black levels right, because it’s a very dark film. Kinski’s performance, however, has lost some of the luster it apparently had when critics like Ebert spoke so highly of it contemporaneously; or perhaps it’s our eyes that have changed. Like most of Kinski’s work, his Dracula is far more remarkable for the grand stories around it (many of which were intentionally aggrandized for public consumption, as Herzog points out in his commentary, tastefully silent on his level of direct participation in this) than for the performance itself. Adjani gives the best performance when compared against the material she’s given, and Bruno Ganz is a true professional, his talents somewhat wasted in the most boring Hutter/Harker role yet.

There actually is a next adventure in this ersatz “franchise,” though Ganz would not be returning to reprise his role as Nosferatu-Harker; this movie got a non-Herzog-directed sequel a decade later that was an absolute disaster to film because Herzog was more or less the only director on the planet who would or could shoot a full feature with Kinski. We may at some point take a look at Vampire in Venice, but there’s more pressing business to attend to first: Shadow of the Vampire will be next week’s film, closing out the Murnau tree of Nosferatus, and then in the first round of patron voting over on our Patreon, it was decided that Coppola’s 1992 Bram Stoker’s Dracula will be the film after that. We’re still assembling the film roster out into the future, but never fear: 2014 Dracula Untold is in there somewhere, just waiting. I look forward to seeing Charles Dance as Nosferatu again, even if the Universal Pictures Dark Universe’s games never did end up beginning.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.